Charles X of France

| Charles X | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Portrait by Baron Gérard, c.1829 | |||||

| King of France and Navarre | |||||

| Reign | 16 September 1824 – 2 August 1830 | ||||

| Coronation | 29 May 1825 | ||||

| Predecessor | Louis XVIII | ||||

| Successor |

Louis Philippe I as King of the French | ||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||

| Born |

9 October 1757 Palace of Versailles, France | ||||

| Died |

6 November 1836 (aged 79) Görz, Austria (now in Italy) | ||||

| Burial | Kostanjevica Monastery, Slovenia | ||||

| Spouse | Marie Thérèse of Savoy | ||||

| Issue |

Louis XIX Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry | ||||

| |||||

| House | Bourbon | ||||

| Father | Louis, Dauphin of France | ||||

| Mother | Marie Josèphe of Saxony | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature |

| ||||

Charles X (Charles Philippe; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830.[1] For most of his life he was known as the Count of Artois (in French, comte d'Artois). An uncle of the uncrowned King Louis XVII, and younger brother to reigning Kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile and eventually succeeded him.[2]

His rule of almost six years ended in the July Revolution of 1830, which resulted in his abdication and the election of Louis Philippe, Duke of Orléans, as King of the French. Exiled once again, Charles died in 1836 in Gorizia, then part of the Austrian Empire.[3] He was the last of the French rulers from the senior branch of the House of Bourbon.

Childhood and adolescence

Charles Philippe of France was born in 1757, the youngest son of the Dauphin Louis and his wife, the Dauphine Marie Josèphe, at the Palace of Versailles. Charles was created Count of Artois at birth by his grandfather, the reigning King Louis XV. As the youngest male in the family, Charles seemed unlikely ever to become king. His eldest brother, Louis, Duke of Burgundy, died unexpectedly in 1761, which moved Charles up one place in the line of succession. He was raised in early childhood by Madame de Marsan, the Governess of the Children of France.

At the death of his father in 1765, Charles's oldest surviving brother, Louis Auguste, became the new Dauphin (the heir apparent to the French throne). Their mother Marie Josèphe, who never recovered from the loss of her husband, died in March 1767 from tuberculosis.[4] This left Charles an orphan at the age of nine, along with his siblings Louis Auguste, Louis Stanislas, Count of Provence, Clotilde ("Madame Clotilde"), and Élisabeth ("Madame Élisabeth").

Louis XV fell ill on 27 April 1774 and died on 10 May of smallpox at the age of 64.[5] His grandson Louis-Auguste succeeded him as King Louis XVI of France.[6]

Marriage and private life

In November 1773, Charles married Marie Thérèse of Savoy. The marriage, unlike that of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, was consummated almost immediately.[7]

In 1775, Marie Thérèse gave birth to a boy, Louis Antoine, who was created Duke of Angoulême by Louis XVI. Louis-Antoine was the first of the next generation of Bourbons, as the king and the Count of Provence had not fathered any children yet, causing the Parisian libellistes (pamphleteers who published scandalous leaflets about important figures in court and politics) to lampoon Louis XVI's alleged impotence.[8] Three years later, in 1778, Charles' second son, Charles Ferdinand, was born and given the title of Duke of Berry.[9] In the same year Queen Marie Antoinette gave birth to her first child, Marie Thérèse, quelling all rumours that she could not bear children.

Charles was thought of as the most attractive member of his family, bearing a strong resemblance to his grandfather Louis XV.[10] His wife was considered quite ugly by most contemporaries, and he looked for company in numerous extramarital affairs. According to the Count of Hézecques, "few beauties were cruel to him." Later, he embarked upon a lifelong love affair with the beautiful Louise de Polastron, the sister-in-law of Marie Antoinette's closest companion, the Duchess of Polignac.

Charles also struck up a firm friendship with Marie Antoinette herself, whom he had first met upon her arrival in France in April 1770 when he was twelve.[10] The closeness of the relationship was such that he was falsely accused by Parisian rumour mongers of having seduced her. As part of Marie Antoinette's social set, Charles often appeared opposite her in the private theatre of her favourite royal retreat, the Petit Trianon. They were both said to be very talented amateur actors. Marie Antoinette played milkmaids, shepherdesses, and country ladies, whereas Charles played lovers, valets, and farmers.

A famous story concerning the two involves the construction of the Château de Bagatelle. In 1775, Charles purchased a small hunting lodge in the Bois de Boulogne. He soon had the existing house torn down with plans to rebuild. Marie Antoinette wagered her brother-in-law that the new château could not be completed within three months. Charles engaged the neoclassical architect François-Joseph Bélanger to design the building.[11]

He won his bet, with Bélanger completing the house in sixty-three days. It is estimated that the project, which came to include manicured gardens, cost over two million livres. Throughout the 1770s, Charles spent lavishly. He accumulated enormous debts, totalling 21 million livres. In the 1780s, King Louis XVI paid off the debts of both his brothers, the Counts of Provence and Artois.[12]

In 1781, Charles acted as a proxy for Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II at the christening of his godson, the Dauphin Louis Joseph.[13]

Crisis and French Revolution

Charles's political awakening started with the first great crisis of the monarchy in 1786, when it became apparent that the kingdom was bankrupt from previous military endeavours (in particular the Seven Years' War and the American War of Independence) and needed fiscal reform to survive. Charles supported the removal of the aristocracy's financial privileges, but was opposed to any reduction in the social privileges enjoyed by either the Church or the nobility. He believed that France's finances should be reformed without the monarchy being overthrown. In his own words, it was "time for repair, not demolition."

King Louis XVI eventually convened the Estates General, which had not been assembled for over 150 years, to meet in May 1789 to ratify financial reforms. Along with his sister Élisabeth, Charles was the most conservative member of the family[14] and opposed the demands of the Third Estate (representing the commoners) to increase their voting power. This prompted criticism from his brother, who accused him of being "plus royaliste que le roi" ("more royalist than the king"). In June 1789, the representatives of the Third Estate declared themselves a National Assembly intent on providing France with a new constitution.[15]

In conjunction with the Baron de Breteuil, Charles had political alliances arranged to depose the liberal minister of finance, Jacques Necker. These plans backfired when Charles attempted to secure Necker's dismissal on 11 July without Breteuil's knowledge, much earlier than they had originally intended. It was the beginning of a decline in his political alliance with Breteuil, which ended in mutual loathing.

Necker's dismissal provoked the storming of the Bastille on 14 July. At the insistence of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, Charles and his family left France three days later, on 17 July, along with several other courtiers, including the Duchess of Polignac, the queen’s favourite.[16] His flight has historically been largely attributed to personal fears for his own safety. However recent research indicates that the King approved in advance of his brother's departure, seeing it as a means of ensuring that one close relative would be free to act as a spokesman for the monarchy after Louis himself had been removed from Versailles to Paris.[17]

Life in exile

Charles and his family decided to seek refuge in Savoy, his wife's native country,[18] where they were joined by some members of the Condé family.[19] Meanwhile, in Paris, Louis XVI was struggling with the National Assembly, which was committed to radical reforms and had enacted the Constitution of 1791. In March 1791, the Assembly also enacted a regency bill that provided for the case of the king's premature death. While his heir Louis-Charles was still a minor, the Count of Provence, the Duke of Orléans or, if either was unavailable, someone chosen by election should become regent, completely passing over the rights of Charles who, in the royal lineage, stood between the Count of Provence and the Duke of Orléans.[20]

Charles meanwhile left Turin and moved to Trier, where his uncle, Clemens Wenceslaus of Saxony, was the incumbent Archbishop-Elector. Charles prepared for a counter-revolutionary invasion of France, but a letter by Marie Antoinette postponed it until after the royal family had escaped from Paris and joined a concentration of regular troops under General de Bouillé at Montmédy.[21][22]

After the attempted flight was stopped at Varennes, Charles moved on to Koblenz, where he, the recently escaped Count of Provence and the Princes of Condé jointly declared their intention to invade France. The Count of Provence was sending dispatches to various European sovereigns for assistance, while Charles set up a court-in-exile in the Electorate of Trier. On 25 August, the rulers of the Holy Roman Empire and Prussia issued the Declaration of Pillnitz, which called on other European powers to intervene in France.[23]

On New Year's Day 1792, the National Assembly declared all emigrants traitors, repudiated their titles and confiscated their lands.[24] This measure was followed by the suspension and eventually the abolition of the monarchy in September 1792. The royal family was imprisoned and the king and queen were eventually put to death in 1793.[25] The young Dauphin died of illnesses and neglect in 1795.[26]

When the French Revolutionary Wars broke out in 1792, Charles escaped to Great Britain, where King George III of Great Britain gave him a generous allowance. Charles lived in Edinburgh and London with his mistress Louise de Polastron[27] His older brother, dubbed Louis XVIII after the death of his nephew in June 1795, relocated to Verona and then to Jelgava Palace, Mitau, where Charles' son Louis Antoine married Louis XVI's only surviving child, Marie Thérèse, on 10 June 1799. In 1802, Charles supported his brother with several thousand pounds. In 1807, Louis XVIII moved to Great Britain.[28]

The Bourbon Restoration

In January 1814, Charles covertly left his home in London to join the Coalition forces in southern France. Louis XVIII, by then wheelchair-bound, supplied Charles with letters patent creating him Lieutenant General of the kingdom. On 31 March, the Allies captured Paris. A week later, Napoleon I abdicated. The Senate declared Louis XVIII restored. Charles arrived in the capital on 12 April[29] and acted as Lieutenant General of the kingdom until Louis XVIII arrived from England. During his brief tenure as regent, Charles created an ultra-royalist secret police that reported directly back to him without Louis XVIII's knowledge. It operated for over five years.[30]

Louis XVIII was greeted with great rejoicing from the Parisians and proceeded to occupy the Tuileries Palace.[31] The Count of Artois lived in the Pavillon de Mars, and the Duke of Angoulême in the Pavillon de Flore, which overlooked the River Seine.[32] The Duchess of Angoulême fainted upon arriving at the palace, as it brought back terrible memories of her family's incarceration there, and of the storming of the palace and the massacre of the Swiss Guards on 10 August 1792.[31]

Following the advice of the occupying allied army, Louis XVIII drafted a liberal constitution, the Charter of 1814, which entailed a bicameral legislature, an electorate of 90,000 men and freedom of religion.[33]

After the Hundred Days, Napoleon's brief return to power in 1815,[34] the White Terror focused mainly on the purging of a civilian administration which had almost completely turned against the Bourbon monarchy. About 70,000 officials were dismissed from their positions. The remnants of the Napoleonic army were disbanded after Waterloo and its senior officers cashiered. Marshal Ney was executed for treason, and Marshal Brune was murdered by a crowd.[35] Approximately 6,000 individuals who had rallied to Napoleon were brought to trial. There were about 300 mob lynchings in the south of France, notably in Marseilles where a number of Napoleon's Mamluks preparing to return to Egypt, were massacred in their barracks.

The king's brother and heir presumptive

While the king retained the liberal charter, Charles patronised members of the ultra-royalists in parliament, such as Jules de Polignac, the writer François-René de Chateaubriand and Jean-Baptiste de Villèle.[36] On several occasions, Charles voiced his disapproval of his brother's liberal ministers and threatened to leave the country unless Louis XVIII dismissed them.[37] Louis, in turn, feared that his brother’s and heir presumptive’s ultra-royalist tendencies would send the family into exile once more (which they eventually did).

On 14 February 1820, Charles’s younger son, the Duke of Berry, was assassinated at the Paris Opera. This loss not only devastated the family but also put the continuation of the Bourbon dynasty in jeopardy, as the Duke of Angoulême’s marriage had not produced any children. Parliament debated the abolition of the Salic law, which excluded females from the succession and was long held inviolable. However, the Duke of Berry’s widow, Caroline of Naples and Sicily, was found to be pregnant and on 29 September 1820 gave birth to a son, Henry, Duke of Bordeaux.[38] His birth was hailed as "God-given", and the people of France bought for him the Château de Chambord in celebration of his birth.[39] As a result, his granduncle, Louis XVIII, added the title Count of Chambord, hence Henry, Count of Chambord, the name by which he is usually known.

Reign

Internal policies

Louis XVIII's health had been worsening since the beginning of 1824.[40] Suffering from both dry and wet gangrene in his legs and spine, he died on 16 September of that year. His brother succeeded him to the throne as King Charles X of France.[41] In his first act as king, Charles attempted to unify the House of Bourbon by granting the style of Royal Highness to his cousins of the House of Orléans, who had been deprived of this by Louis XVIII because of the former Duke of Orléans' role in the death of Louis XVI.

While his brother had been sober enough to realize that France would never accept an attempt to resurrect the Ancien Régime, Charles had never been willing to accept the changes of the past four decades. He gave his Prime Minister, Jean-Baptiste de Villèle, lists of laws that he wanted ratified every time he opened parliament. In April 1825, the government approved legislation proposed by Louis XVIII but implemented only after his death, that paid an indemnity to nobles whose estates had been confiscated during the Revolution (the biens nationaux).[42]

The law gave government bonds to those who had lost their lands in exchange for their renunciation of their ownership. This cost the state approximately 988 million francs. In the same month, the Anti-Sacrilege Act was passed. Charles's government attempted to re-establish male only primogeniture for families paying over 300 francs in tax, but the measure was voted down in the Chamber of Deputies.[42]

On 29 May 1825, King Charles was anointed at the cathedral of Reims, the traditional site of consecration of French kings; it had been unused since 1775, as Louis XVIII had foregone the ceremony to avoid controversy.[43] It was in the venerable cathedral of Notre-Dame at Paris that Napoleon had consecrated his revolutionary empire; but in ascending the throne of his ancestors, Charles reverted to the old place of coronation used by the kings of France from the early ages of the monarchy.[44]

That Charles was not a popular ruler became apparent in April 1827, when chaos ensued during the king's review of the National Guard in Paris. In retaliation, the National Guard was disbanded but, as its members were not disarmed, it remained a potential threat.[43] After losing his parliamentary majority in a general election in November 1827, Charles dismissed Prime Minister Villèle on 5 January 1828 and appointed Jean-Baptise de Martignac, a man the king disliked and thought of only as provisional. On 5 August 1829, Charles dismissed Martignac and appointed Jules de Polignac, who, however, lost his majority in parliament at the end of August, when the Chateaubriand faction defected. To stay in power, Polignac would not recall the Chambers until March 1830.[45]

Conquest of Algeria

On 31 January 1830, the Polignac government decided to send a military expedition to Algeria to put an end to the threat the Algerian pirates posed to Mediterranean trade and also increase the government's popularity with a military victory. The reason given for the war was that the Viceroy of Algeria, angry about French failure to pay debts stemming from Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, had struck the French consul with the handle of his fly swat.[45] French troops invaded Algiers on 5 July.[46]

The July Revolution

The Chambers convened on 2 March 1830, as planned, but Charles's opening speech was greeted by negative reactions from many deputies. Some introduced a bill requiring the King's minister to obtain the support of the Chambers. On 18 March, 221 deputies, a majority of 30, voted in favor of the bill. However, the King had already decided to hold general elections, and the chamber was suspended on 19 March.[47]

Elections were held on 23 June, but did not produce a majority favorable to the government. On 6 July, the king and his ministers decided to suspend the constitution, as provided for in Article 14 of the Charter in case of an emergency, and on 25 July, from the royal residence in Saint-Cloud, issued four ordinances that censored the press, dissolved the newly elected chamber, altered the electoral system, and called for elections in September.[46]

When the official government newspaper, Le Moniteur Universel, published the ordinances on Monday, 26 July, Adolphe Thiers, journalist at the opposition paper Le National, published a call to revolt, which was signed by forty-three journalists:[48] "The legal regime has been interrupted: that of force has begun... Obedience ceases to be a duty!"[49] In the evening, crowds assembled in the gardens of the Palais-Royal, shouting "Down with the Bourbons!" and "Vive la Charte!". As the police closed off the gardens during the nights, the crowd re-grouped in a nearby street, where they shattered streetlamps.[50]

The next morning, 27 July, police raided and shut down the newspapers that continued to publish (including Le National). When the protesters, who had re-entered the Palais-Royal gardens, heard of this, they threw stones at the soldiers, prompting them to shoot. By evening, the city was dominated by violence and shops were looted. On 28 July, the rioters began to erect barricades in the streets. Marshal Marmont, who had been called in the day before to remedy the situation, took the offensive against the rioters, but some of his men defected to the rioters, and by afternoon he had to retreat to the Tuileries Palace.[51]

The members of the Chamber of Deputies sent a five-man delegation to Marmont, urging him to advise the king to assuage the protesters by revoking the four Ordinances. On Marmont's request, the prime minister applied to the king, but Charles refused all compromise and dismissed his ministers that afternoon, realizing the precariousness of the situation. That evening, the members of the Chamber assembled at Jacques Laffitte's house and decided that Louis Philippe d'Orléans should take the throne from King Charles. They printed posters endorsing Louis Philippe and distributed them throughout the city. By the end of the day, the government's authority was trampled.[52]

A few minutes after midnight on 31 July, warned by General Gresseau that Parisians were planning to attack the residence, Charles X decided to leave Saint-Cloud and seek refuge in Versailles with his family and the court, with the exception of the Duke of Angoulême, who stayed behind with the troops, and the Duchess of Angoulême, who was taking the waters at Vichy. Meanwhile, in Paris, Louis Philippe assumed the post of Lieutenant General of the Kingdom.[53]

The road to Versailles was filled with disorganized troops and deserters. The Marquis de Vérac, governor of the Palace of Versailles, came to meet the king before the royal cortège entered the town, to tell him that the palace was not safe, as the Versailles national guards wearing the revolutionary tricolor were occupying the Place d'Armes. Charles X then gave the order to go to the Trianon. It was five in the morning.[54] Later that day, after the arrival of the Duke of Angoulême from Saint-Cloud with his troops, Charles X ordered a departure for Rambouillet, where they arrived shortly before midnight. On the morning of 1 August, the Duchess of Angoulême, who had rushed from Vichy after learning of events, arrived at Rambouillet.

The following day, 2 August, Charles X abdicated, bypassing his son the Dauphin in favor of his grandson Henry, Duke of Bordeaux, who was not yet ten years old. At first, the Duke of Angoulême (the Dauphin) refused to countersign the document renouncing his rights to the throne of France. According to the Duchess of Maillé, "there was a strong altercation between the father and the son. We could hear their voices in the next room." Finally, after twenty minutes, the Duke of Angoulême reluctantly countersigned the following declaration:[55]

“My cousin, I am too deeply pained by the ills that afflict or could threaten my people, not to seek means of avoiding them. Therefore, I have made the resolution to abdicate the crown in favor of my grandson, the Duke of Bordeaux. The Dauphin, who shares my feelings, also renounces his rights in favor of his nephew. It will thus fall to you, in your capacity as Lieutenant General of the Kingdom, to proclaim the accession of Henri V to the throne. Furthermore, you will take all pertinent measures to regulate the forms of government during the new king’s minority. Here, I limit myself to stating these arrangements, as a means of avoiding further evils. You will communicate my intentions to the diplomatic corps, and you will let me know as soon as possible the proclamation by which my grandson will be recognized as king under the name of Henri V.” [56]

Louis Philippe ignored the document and on 9 August had himself proclaimed King of the French by the members of the Chamber.[57]

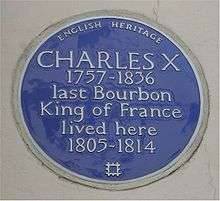

Second exile and death

When it became apparent that a mob of 14,000 people was preparing to attack, the royal family left Rambouillet and, on 16 August, embarked for the United Kingdom on packet steamers provided by Louis Philippe. Informed by the British Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, that they needed to arrive in England as private citizens, all family members adopted pseudonyms; Charles X styled himself "Count of Ponthieu". The Bourbons were greeted coldly by the English, who upon their arrival mockingly waved the newly adopted tri-colour flags at them.[58]

Charles X was quickly followed to Britain by his creditors, who had lent him vast sums during his first exile and were yet to be paid back in full. However, the family was able to use money Charles's wife had deposited in London.[58]

The Bourbons were allowed to reside in Lulworth Castle in Dorset, but quickly moved to Holyrood Palace in Edinburgh,[58] where the Duchess of Berry also lived at Regent Terrace[59]

Charles' relationship with his daughter-in-law proved uneasy, as the Duchess claimed the regency for her son Henry, whom the abdications of Rambouillet had left the legitimist pretender to the French throne. Charles at first denied her demands, but in December agreed to support her claim[60] once she had landed in France.[59] In 1831 the Duchess made her way from Britain by way of the Netherlands, Prussia and Austria to her family in Naples.[59]

Having gained little support, she arrived in Marseilles in April 1832,[59] made her way to the Vendée, where she tried to instigate an uprising against the new regime, and was imprisoned, much to the embarrassment of her father-in-law.[60] He was further dismayed when after her release the Duchess married the Count of Lucchesi Palli, a minor Neapolitan noble. In response to this morganatic match, Charles banned her from seeing her children.[61]

At the invitation of Emperor Francis I of Austria, the Bourbons moved to Prague in winter 1832/33 and were given lodging at the Hradschin Palace by the Emperor.[60] In September 1833, Bourbon legitimists gathered in Prague to celebrate the Duke of Bordeaux's thirteenth birthday. They expected grand celebrations, but Charles X merely proclaimed his grandson's majority.[62]

On the same day, after much cajoling by Chateaubriand, Charles agreed to a meeting with his daughter-in-law, which took place in Leoben on 13 October 1833. The children of the Duchess refused to meet her after they learned of her second marriage. Charles refused the various demands by the Duchess, but after protests from his other daughter-in-law, the Duchess of Angoulême, acquiesced. In the summer of 1834, he again allowed the Duchess of Berry to see her children.[63]

Upon the death of Emperor Francis in March 1835, the Bourbons left Prague Castle, as the new Emperor Ferdinand wished to use it for coronation ceremonies. The Bourbons moved initially to Teplitz. Then, as Ferdinand wanted the continued use of Prague Castle, purchased Kirchberg Castle. Moving there was postponed due to an outbreak of cholera in the locality.[64]

In the meantime, Charles left for the warmer climate on Austria's Mediterranean coast in October 1835. Upon his arrival at Görz (Gorizia) in the Kingdom of Illyria, he caught cholera and died on 6 November 1836. The townspeople draped their windows in black to mourn him. Charles was interred in the Church of the Annunciation of Our Lady, in the Franciscan Kostanjevica Monastery (now in Nova Gorica, Slovenia).[65] His remains lie in a crypt with those of his family.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Charles X of France |

|---|

Marriage and issue

Charles X married Princess Maria Teresa of Savoy, the daughter of Victor Amadeus III, King of Sardinia and Maria Antonietta of Spain, on 16 November 1773. The couple had four children - two sons and two daughters - but the daughters did not survive childhood. Only the oldest son survived his father. The children were:

- Louis Antoine, Duke of Angoulême (6 August 1775 – 3 June 1844) Louis Antoine d'Artois, sometimes called Louis XIX

- Sophie (5 August 1776 – 5 December 1783) Sophie d'Artois

- Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry (24 January 1778 – 13 February 1820) Charles Ferdinand d'Artois

- Marie Thérèse (1783) Marie Thérèse d'Artois

In fiction and film

The Count of Artois is portrayed by Al Weaver in Sofia Coppola's motion picture Marie Antoinette.

References

- ↑ Mary Platt Parmele, A Short History of France. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons (1894), p. 221.

- ↑ Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions, Macmillan, p. 185-187.

- ↑ Munro Price, The Perilous Crown: France between Revolutions, Macmillan, p. 185-187.

- ↑ Évelyne Lever, Louis XVI, Librairie Arthème Fayard, Paris (1985), p. 43

- ↑ Antonia Fraser, Marie Antoinette: the Journey, p. 113–116.

- ↑ Charles Porset, Hiram sans-culotte? Franc-maçonnerie, lumières et révolution: trente ans d'études et de recherches, Paris: Honoré Champion, 1998 p. 207.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 128-129.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 137–139.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 189.

- 1 2 Fraser, p. 80-81.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 178.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 178.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 221.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 326.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 274–278.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 338.

- ↑ Price, Monro. The Fall of the French Monarchy. pp. 93–94. ISBN 0330488279.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 340.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 65.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 383.

- ↑ Price, Monro. The Fall of the French Monarchy. ISBN 0-330-48827-9.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 103.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 113.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 118.

- ↑ Fraser, p. 399, 440, 456; Nagel, p. 143.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 152-153.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 207.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 210, 222, 233–235

- ↑ Nagel, p. 153.

- ↑ Price, p. 11-12.

- 1 2 Nagel, p. 253-254.

- ↑ Price, p. 50.

- ↑ Price, p. 52-54.

- ↑ Price, p. 72, 80–83

- ↑ Price, p. 84.

- ↑ Price, p. 91-92.

- ↑ Price, p. 94-95.

- ↑ Price, p. 109.

- ↑ McConnachie, James (2004). Rough Guide to the Loire. London: Rough Guides. p. 144. ISBN 978-1843532576.

- ↑ Lever, Évelyne, Louis XVIII, Librairie Arthème Fayard, Paris, 1988, p. 553. (French).

- ↑ Price, p. 113-115.

- 1 2 Price, p. 116-118.

- 1 2 Price, p. 119-121.

- ↑ T W Redhead (January 2012). The French Revolutions. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 176. ISBN 978-3-86403-428-2. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- 1 2 Price, p. 122-128.

- 1 2 Price, p. 136-138.

- ↑ Price, p. 130-132.

- ↑ Castelot, André, Charles X, Librairie Académique Perrin, Paris, 1988, p. 454 ISBN 2-262-00545-1

- ↑ Le régime légal est interrompu; celui de la force a commencé... L'obéissance cesse d'être un devoir!

- ↑ Price, p. 141-142.

- ↑ Price, p. 151-154, 157.

- ↑ Price, p. 158, 161–163.

- ↑ Price, p. 173-176.

- ↑ Castelot, Charles X, p. 482.

- ↑ Castelot, Charles X, p. 491

- ↑ Charles X's abdication: “Mon cousin, je suis trop profondément peiné des maux qui affligent ou qui pourraient menacer mes peuples pour n’avoir pas cherché un moyen de les prévenir. J’ai donc pris la résolution d’abdiquer la couronne en faveur de mon petit-fils, le duc de Bordeaux. Le dauphin, qui partage mes sentiments, renonce aussi à ses droits en faveur de son neveu. Vous aurez donc, en votre qualité de lieutenant général du royaume, à faire proclamer l’avènement de Henri V à la couronne. Vous prendrez d’ailleurs toutes les mesures qui vous concernent pour régler les formes du gouvernement pendant la minorité du nouveau roi. Ici, je me borne à faire connaître ces dispositions : c’est un moyen d’éviter encore bien des maux. Vous communiquerez mes intentions au corps diplomatique, et vous me ferez connaître le plus tôt possible la proclamation par laquelle mon petit-fils sera reconnu roi sous le nom de Henri V. »

- ↑ Price, p. 177, 181–182, 185.

- 1 2 3 Nagel, p. 318-325

- 1 2 3 4 A.J. Mackenzie-Stuart, A French King at Holyrood, Edinburgh (1995). ISBN 0-85976-413-3

- 1 2 3 Nagel, p. 327-328.

- ↑ Nagel, pp. 322, 333.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 340-342.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 340-342.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 349-350.

- ↑ Nagel, p. 349-350.

External links

Media related to Charles X of France at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles X of France at Wikimedia Commons "Charles X". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

"Charles X". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

| Charles X of France Cadet branch of the Capetian dynasty Born: 9 October 1757 Died: 6 November 1836 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Louis XVIII |

King of France and Navarre 16 September 1824 – 2 August 1830 |

Succeeded by Louis Philippe as King of the French |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Vacant Title last held by Louis XVIII |

— TITULAR — King of France and Navarre 2 August 1830 – 6 November 1836 Reason for succession failure: July Revolution |

Succeeded by Louis XIX |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

.svg.png)