Quercus robur

| Quercus robur | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leaves and acorns (note the long acorn stalks) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Quercus |

| Section: | Quercus |

| Species: | Q. robur |

| Binomial name | |

| Quercus robur L. | |

| |

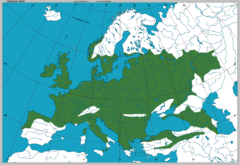

| Quercus robur distribution | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

List

| |

Quercus robur is commonly known as the English oak or pedunculate oak or French oak. It is native to most of Europe to the Caucasus, and also in Anatolia. The tree is widely cultivated in temperate regions and has escaped into the wild in scattered parts of China and North America.[2][3]

Taxonomy

Quercus robur (Latin quercus, "oak" + robur "strength, hard timber") is the type species of the genus (the species by which the oak genus Quercus is defined), and a member of the white oak section Quercus section Quercus. The populations in Italy, southeast Europe, and Asia Minor and the Caucasus are sometimes treated as separate species, Q. brutia Tenore, Q. pedunculiflora K. Koch and Q. haas Kotschy respectively.

A close relative is the sessile oak (Q. petraea), which shares much of its range. Q. robur is distinguished from this species by its leaves having only a very short stalk 3–8 mm (0.12–0.31 in) long, and by its pedunculate (stalked) acorns. The two often hybridise in the wild, the hybrid being known as Quercus × rosacea.

Description

Quercus robur is a large deciduous tree, with circumference of grand oaks from 4 m (13 ft) to exceptional 12 m (39 ft). The Majesty Oak with a circumference of 12.2 m (40 ft) is the thickest tree in Great Britain, and the Kaive Oak in Latvia with a circumference of 10.2 m (33 ft) is the thickest tree in Northern Europe. Quercus robur has lobed and nearly sessile (very short-stalked) leaves 7–14 cm (2.8–5.5 in) long. Flowering takes place in mid spring, and their fruit, called acorns, ripen by the following autumn. The acorns are 2–2.5 cm (0.79–0.98 in) long, pedunculate (having a peduncle or acorn-stalk, 3–7 cm (1.2–2.8 in) long) with one to four acorns on each peduncle.

It is a long-lived tree, with a large wide spreading crown of rugged branches. While it may naturally live to an age of a few centuries, many of the oldest trees are pollarded or coppiced, both pruning techniques that extend the tree's potential lifespan, if not its health. Two individuals of notable longevity are the Stelmužė Oak in Lithuania and the Granit Oak in Bulgaria, which are believed to be more than 1,500 years old, possibly making them the oldest oaks in Europe; another specimen, called the 'Kongeegen' ('Kings Oak'), estimated to be about 1,200 years old, grows in Jaegerspris, Denmark. Yet another can be found in Kvilleken, Sweden, that is over 1,000 years old and 14 metres (46 ft) around.[4] Of maiden (not pollarded) specimens, one of the oldest is the great oak of Ivenack, Germany. Tree-ring research of this tree and other oaks nearby gives an estimated age of 700 to 800 years. Also the Bowthorpe Oak in Lincolnshire, England is estimated to be 1,000 years old, making it the oldest in the UK, although there is Knightwood Oak in the New Forest which is also said to be as old. Highest density of the grand oak trees Q. robur with a circumference 4 metres (13 ft) and more is in Latvia.[5]

Ecological importance

Within its native range Q. robur is valued for its importance to insects and other wildlife. Numerous insects live on the leaves, buds, and in the acorns. Q.robur supports the highest biodiversity of insect herbivores of any British plant (>400 spp). The acorns form a valuable food resource for several small mammals and some birds, notably Eurasian jays Garrulus glandarius. Jays were overwhelmingly the primary propagators[6] of oaks before humans began planting them commercially, because of their habit of taking acorns from the umbra of its parent tree and burying it undamaged elsewhere. Mammals, notably squirrels who tend to hoard acorns and other nuts most often leave them too abused to grow in the action of moving or storing them.

Commercial forestry

Quercus robur is planted for forestry, and produces a long-lasting and durable heartwood, much in demand for interior and furniture work. The wood of Q. robur is identified by a close examination of a cross-section perpendicular to fibres. The wood is characterised by its distinct (often wide) dark and light brown growth rings. The earlywood displays a vast number of large vessels (~0.5 mm (0.020 in) diameter). There are rays of thin (~0.1 mm (0.0039 in)) yellow or light brown lines running across the growth rings. The timber is around 720 kg (1,590 lb) per cubic meter in density.[7]

Cultivation

A number of cultivars are grown in gardens and parks and in arboreta and botanical gardens. The most common cultivar is Quercus robur 'Fastigiata', and is the exception among Q. robur cultivars which are generally smaller than the standard tree, growing to between 10–15 m and exhibit unusual leaf or crown shape characteristics.

- In Australia

English oak is one of the most common park trees in south-eastern Australia, noted for its vigorous, luxuriant growth. In Australia, it grows very quickly to a tree of 20 m (66 ft) tall by up to 20 m (66 ft) broad, with a low-branching canopy. Its trunk and secondary branches are very thick and solid and covered with deep-fissured blackish-grey bark.[8] The largest example in Australia is in Donnybrook, Western Australia.[9] Native Australian oaks are quite unrelated to the European oaks.

Cultivars

- Quercus robur 'Fastigiata' ("Cypress Oak"), probably the most common cultivated form, it grows to a large imposing tree with a narrow columnar habit. The fastigiate oak was originally propagated from an upright tree that was found in central Europe.

- Quercus robur 'Concordia' ("Golden Oak"), a small very slow-growing tree, eventually reaching 10 m (33 ft), with bright golden-yellow leaves throughout spring and summer. It was originally raised in Van Geert's nursery at Ghent in 1843.

- Quercus robur 'Pendula' ("Weeping Oak"), a small to medium-sized tree with pendulous branches, reaching up to 15 m.

- Quercus robur 'Purpurea' is another cultivar growing to 10 m (33 ft), but with purple coloured leaves.

- Quercus robur 'Filicifolia' ("Cut-leaved Oak") is a cultivar where the leaf is pinnately divided into fine forward pointing segments.

Hybrids

Along with the naturally occurring Q. × rosacea, several hybrids with other white oak species have also been produced in cultivation, including Turner's Oak Q. × turnerii, Heritage Oak Q. × macdanielli, and Two Worlds Oak Q. × bimundorum, the latter two developed by nurseries in the United States.

- Q. × bimundorum (Q. alba × Q. robur) (Two Worlds Oak)

- Q. × macdanielli (Q. macrocarpa × Q. robur) (Heritage Oak)

- Q. × rosacea Bechst. (Q. petraea x Q. robur), a hybrid of the sessile oak and English oak. It is usually of intermediate character between its parents, however it does occasionally exhibit more pronounced characteristics of one or the other parent.

- Q. × turnerii Willd. (Q. ilex × Q. robur) (Turner's Oak), a semi-evergreen tree of small to medium size with a rounded crown; it was originally raised at Mr. Turner's nursery, Essex, UK, in 1783. An early specimen is at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.[10]

- Q. × warei (Q. robur fastigiata x Q. bicolor), a hybrid between Upright English Oak and the swamp white oak. The selections within this hybrid include the (Regal Prince) 'Long'[11] cultivar and the (Kindred Spirit) 'Nadler' cultivar.[12]

Diseases

Symbolism

Basque Country

In the Basque Country (Spain)and (France) the oak symbolises the traditional basque liberties. This is based on the 'tree of Gernika', an ancient oak tree located in Gernika, below which since at least the 13th century the Lords of Biscay first, and afterwards their successors the Kings of Castile and the Kings of Spain solemnly swore to uphold the charter of Biscay, which secured widespread rights to the inhabitants of Biscay. Since the 14th century, the Juntas Generales (the parliament of Biscay) gathers in a building next to the oak tree, and symbolically passes its laws under the tree as well. Nowadays, the Lehendakari (Basque prime minister) swears his oath of office under the tree.

Bulgaria

The national coat of arms of Bulgaria includes two crossed oak branches with fruits - as shield (escutcheon) compartment.

Croatia

Oak leaves with acorns are depicted on the reverse of the Croatian 5 lipa coin, minted since 1993.[14] The pedunculate oak of the Croatian region of Slavonia (considered a separate subspecies - Slavonian oak) is a regional symbol of Slavonia and a national symbol of Croatia.[15]

England

In England, the English oak has assumed the status of a national emblem. This has its origins in the oak tree at Boscobel House, where the future King Charles II hid from his Parliamentarian pursuers in 1650 during the English Civil War; the tree has since been known as the Royal Oak. This event was celebrated nationally on 29 May as Oak Apple Day, which is continued to this day in some communities.[16] ‘The Royal Oak’ is the third most popular pub name in Britain (541 in 2007)[17] and has been the name of eight major Royal Navy warships. The naval associations are strengthened by the fact that oak was the main construction material for sailing warships. The Royal Navy was often described as ‘The Wooden Walls of Old England’[18] (a paraphrase of the Delphic Oracle) and the Navy’s official quick march is "Heart of Oak". Furthermore, the oak is the most common woodland tree in England.[19] An oak tree has been depicted on the reverse of the pound coin (the 1987 and 1992 issues) and a sprig of oak leaves and acorns is the emblem of the National Trust.

Germany

In Germany, the oak tree is used as a typical object and symbol in romanticism. It can be found in several paintings of Caspar David Friedrich and in "Of the life of a Good-For-Nothing" written by Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff as a symbol of the state protecting every man. In those works the oak is shown in different situations, with leaves and flowers or dead without any of its previous beauty. Those conditions are mostly symbols for the conditions Germany is in or going through. Furthermore, the oak's stem is a symbol for Germany's strength and stability. Oak branches were displayed on the reverse of the small coins of the old Deutsche Mark currency (1 through 10 Pfennigs; the 50 Pfennigs coin showed a woman planting an oak seedling), and are now also displayed on the reverse of the small German-issue Euro currency coins (1 through 5 cents).

Ireland

In Ireland, at Birr Castle, an example, over 400 years old has a girth of 6.5 m. It is known as the Carroll Oak, referring to the local Chieftains, Ely O'Carroll who ruled prior to Norman occupation.[20]

Romania

The Romanian Rugby Union side are also known as The Oaks.

Chemistry

Grandinin/roburin E, castalagin/vescalagin, gallic acid, monogalloyl glucose (glucogallin) and valoneic acid dilactone, monogalloyl glucose, digalloyl glucose, trigalloyl glucose, rhamnose, quercitrin and ellagic acid are phenolic compounds found in Q. robur.[21] The heartwood contains triterpene saponins.[22]

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quercus robur. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Quercus robur |

- ↑ "The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species".

- ↑ Flora of North America, Quercus robur Linnaeus, 1753. English oak, pedunculate oak, chêne pédoncule

- ↑ Flora of China, Quercus robur Linnaeus, 1753. 夏栎 xia li

- ↑ Moström, Jerker (May 2006). "The Oak Tree, from Peasant Torment to a Unifying Concept of Landscape Management" (PDF). The Oak – History, Ecology Management and Planning. Linköping, Sweden: National Heritage Board of Sweden.

- ↑ Eniņš, Guntis (2008). 100 dižākie un svētākie, AS Lauku Avīze, p. 25. ISBN 978-9984-827-15-5

- ↑ White, John (1995). Forest and Woodland Trees in Britain. Oxford University Press. p. 131. ISBN 0-19-854883-4.

- ↑ British Oak. Niche Timbers. Accessed 19-08-2009.

- ↑ "Quercus robur". Metrotrees.com.au. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ Nina Smith (2009-12-10). "Australia's Biggest Oak Tree". Donnybrookmail.com.au. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ "Kew: Plants: Turner’s Oak, Quercus x turneri". Rbgkew.org.uk. 1987-10-16. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ "Plant of the Month". Buckeyegardening.com. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ "''International Oak Society Link''". Oaknames.org. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ "Oak mildew". Forestry Commission. 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Croatian National Bank. Kuna and Lipa, Coins of Croatia: 5 Lipa Coin. – Retrieved on 31 March 2009.

- ↑ "Croatian National Symbols". www.kwintessential.co.uk/. Retrieved 2013-04-23.

- ↑ "Wiltshire - Moonraking - Oak Apple Day". BBC. 1931-05-29. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ "Real Ale and Pub News Features Archive". Solihullcamra.org.uk. 2007-11-15. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ "National Maritime Museum". Nmm.ac.uk. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ Smith, Steve. "The National Inventory of Woodland and Trees - England" (PDF). UK: Forestry Commission. Table 1. p. 52.

- ↑ Fifty Trees of Distinction by Prof. D.A. Webb and the Earl of Ross. Booklet, published by Birr Castle Demesne, 2000.

- ↑ Analysis of oak tannins by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. Pirjo Mämmelä, Heikki Savolainenb, Lasse Lindroosa, Juhani Kangasd and Terttu Vartiainen, Journal of Chromatography A, Volume 891, Issue 1, 1 September 2000, Pages 75-83, doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00624-5

- ↑ Identification of triterpene saponins in Quercus robur L. and Q. petraea Liebl. Heartwood by LC-ESI/MS and NMR. Arramon G, Saucier C, Colombani D and Glories Y, Phytochem Anal., November-DEcember 2002, volume 13, issue 6, pages 305-310, PubMed

- Flora Europaea: Quercus robur

- Bean, W. J. (1976). Trees and shrubs hardy in the British Isles 8th ed., revised. John Murray.

- Rushforth, K. (1999). Trees of Britain and Europe. HarperCollins ISBN 0-00-220013-9.

- (French) Chênes: Quercus robur

External links

- Oaks from Bialowieza Forest in Poland (biggest oak cluster with the monumental sizes in Europe) {English}

- Monumental Trees, Photos and location details of large English oak trees

- Latvia - the land of oaks

- Den virtuella floran - Distribution

|