Suicide

| Suicide | |

|---|---|

The Suicide by Édouard Manet 1877–1881 | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| ICD-10 | X60–X84 |

| ICD-9-CM | E950 |

| DiseasesDB | 12641 |

| MedlinePlus | 001554 |

| eMedicine | article/288598 |

| MeSH | F01.145.126.980.875 |

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Suicide is often carried out as a result of despair, the cause of which is frequently attributed to a mental disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder,[1] alcoholism, or drug abuse,[2] as well as stress factors such as financial difficulties, troubles with interpersonal relationships, and bullying.[3] Suicide prevention efforts include limiting access to method of suicide such as firearms and poisons, treating mental illness and drug misuse, and improving economic conditions. Although crisis hotlines are common, there is little evidence for their effectiveness.[4]

The most commonly used method of suicide varies between countries and is partly related to the availability of effective means. Common methods include: hanging, pesticide poisoning, and firearms.[5] Suicide resulted in 842,000 deaths in 2013. This is up from 712,000 deaths in 1990.[6] This makes it the 10th leading cause of death worldwide.[2][7] Rates of completed suicides are higher in men than in women, with males three to four times more likely to kill themselves than females.[8] There are an estimated 10 to 20 million non-fatal attempted suicides every year.[9] Non-fatal suicide attempts may lead to injury and long-term disabilities. In the Western world, attempts are more common in young people and are four times more common in females than in males.

Views on suicide have been influenced by broad existential themes such as religion, honor, and the meaning of life. The Abrahamic religions traditionally consider suicide an offense towards God due to the belief in the sanctity of life. During the samurai era in Japan, seppuku was respected as a means of atonement for failure or as a form of protest. Sati, a practice outlawed by the British Raj, expected the Indian widow to immolate herself on her husband's funeral pyre, either willingly or under pressure from the family and society.[10] Suicide and attempted suicide, while previously illegal, are no longer in most Western countries. It remains a criminal offense in many countries. In the 20th and 21st centuries, suicide in the form of self-immolation has been used on rare occasions as a medium of protest, and kamikaze and suicide bombings have been used as a military or terrorist tactic.[11] The word is from Latin suicidium, from sui caedere, "to kill oneself".

Definitions

Suicide, also known as completed suicide, is the "act of taking one's own life".[12] Attempted suicide or non-fatal suicidal behavior is self-injury with the desire to end one's life that does not result in death.[13] Assisted suicide is when one individual helps another bring about their own death indirectly via providing either advice or the means to the end.[14] This is in contrast to euthanasia, where another person takes a more active role in bringing about a person's death.[14] Suicidal ideation is thoughts of ending one's life but not taking any active efforts to do so.[13]

There is discussion about the appropriateness of the term "commit" and its use to describe suicide. Those who object to the use of commit argue that it carries with it implications that suicide is a criminal, sinful or morally wrong act.[15] There is growing consensus that it is more appropriate to use "completed suicide," "died by suicide" or simply "killed him/herself" to describe the act of suicide, and this is reflected in mental health organisations' media guidance.[16][17][18][19] Despite these efforts, “committed suicide” or similar descriptions remains common in both scholarly research and journalism.[20][21]

Risk factors

.png)

Factors that affect the risk of suicide include psychiatric disorders, drug misuse, psychological states, cultural, family and social situations, and genetics.[23] Mental illness and substance misuse frequently co-exist.[24] Other risk factors include having previously attempted suicide,[25] the ready availability of a means to take ones life, a family history of suicide, or the presence of traumatic brain injury.[26] For example, suicide rates have been found to be greater in households with firearms than those without them.[27] Socio-economic problems such as unemployment, poverty, homelessness, and discrimination may trigger suicidal thoughts.[28][29] About 15–40% of people leave a suicide note.[30] Genetics appears to account for between 38% and 55% of suicidal behaviors.[31] War veterans have a higher risk of suicide due in part to higher rates of mental illness and physical health problems related to war.[32]

Mental disorders

Mental disorders are often present at the time of suicide with estimates ranging from 27%[33] to more than 90%.[25] Of those who have been admitted to a psychiatric unit, their lifetime risk of completed suicide is about 8.6%.[25] Half of all people who die by suicide may have major depressive disorder; having this or one of the other mood disorders such as bipolar disorder increases the risk of suicide 20-fold.[34] Other conditions implicated include schizophrenia (14%), personality disorders (8%),[35][36] bipolar disorder,[34] and posttraumatic stress disorder.[25] About 5% of people with schizophrenia die of suicide.[37] Eating disorders are another high risk condition.[38]

A history of previous suicide attempts is the greatest predictor of eventual completion of suicide.[25] Approximately 20% of suicides have had a previous attempt, and of those who have attempted suicide, 1% complete suicide within a year[25] and more than 5% die by suicide within 10 years.[38] Acts of self-harm are not usually suicide attempts and most who self-harm are not at high risk of suicide.[39] Some who self-harm, however, do still end their life by suicide, and risk for self-harm and suicide may overlap.[39]

In approximately 80% of completed suicides the individual has seen a physician within the year before their death,[40] including 45% within the prior month.[41] Approximately 25–40% of those who completed suicide had contact with mental health services in the prior year.[33][40] Antidepressants of the SSRI type appear to increase the risk of suicide in children but do not change the risk in adults.[42]

Substance use

Substance abuse is the second most common risk factor for suicide after major depression and bipolar disorder.[43] Both chronic substance misuse as well as acute intoxication are associated.[24][44] When combined with personal grief, such as bereavement, the risk is further increased.[44] Additionally substance misuse is associated with mental health disorders.[24]

Most people are under the influence of sedative-hypnotic drugs (such as alcohol or benzodiazepines) when they die by suicide[45] with alcoholism present in between 15% and 61% of cases.[24] Countries that have higher rates of alcohol use and a greater density of bars generally also have higher rates of suicide.[46] About 2.2–3.4% of those who have been treated for alcoholism at some point in their life die by suicide.[46] Alcoholics who attempt suicide are usually male, older, and have tried to take their own lives in the past.[24] Between 3 and 35% of deaths among those who use heroin are due to suicide (approximately 14 fold greater than those who do not use).[47] In adolescents who misuse alcohol, neurological and psychological dysfunctions may contribute to the increased risk of suicide.[48]

The misuse of cocaine and methamphetamine has a high correlation with suicide.[24][49] In those who use cocaine the risk is greatest during the withdrawal phase.[50] Those who used inhalants are also at significant risk with around 20% attempting suicide at some point and more than 65% considering it.[24] Smoking cigarettes is associated with the risk of suicide.[51] There is little evidence as to why this association exists; however it has been hypothesized that those who are predisposed to smoking are also predisposed to suicide, that smoking causes health problems which subsequently make people want to end their life, and that smoking affects brain chemistry causing a propensity for suicide.[51] Cannabis however does not appear to independently increase the risk.[24]

Problem gambling

Problem gambling is associated with increased suicidal ideation and attempts compared to the general population.[52] Between 12 and 24% pathological gamblers attempt suicide.[53] The rate of suicide among their spouses is three times greater than that of the general population.[53] Other factors that increase the risk in problem gamblers include mental illness, alcohol and drug misuse.[54]

Medical conditions

There is an association between suicidality and physical health problems such as[38] chronic pain,[55] traumatic brain injury,[56] cancer,[57] kidney failure (requiring hemodialysis), HIV, and systemic lupus erythematosus.[38] The diagnosis of cancer approximately doubles the subsequent risk of suicide.[57] The prevalence of increased suicidality persisted after adjusting for depressive illness and alcohol abuse. In people with more than one medical condition the risk was particularly high. In Japan, health problems are listed as the primary justification for suicide.[58]

Sleep disturbances such as insomnia[59] and sleep apnea are risk factors for depression and suicide. In some instances the sleep disturbances may be a risk factor independent of depression.[60] A number of other medical conditions may present with symptoms similar to mood disorders, including hypothyroidism, Alzheimer's, brain tumors, systemic lupus erythematosus, and adverse effects from a number of medications (such as beta blockers and steroids).[25]

Psychosocial states

A number of psychological states increase the risk of suicide including: hopelessness, loss of pleasure in life, depression and anxiousness.[34] A poor ability to solve problems, the loss of abilities one used to have, and poor impulse control also play a role.[34][61] In older adults the perception of being a burden to others is important.[62] Suicide in which the reason is that the person feels that they are not part of society is known as egoistic suicide.[63]

Recent life stresses such as a loss of a family member or friend, loss of a job, or social isolation (such as living alone) increase the risk.[34] Those who have never married are also at greater risk.[25] Being religious may reduce one's risk of suicide.[64] This has been attributed to the negative stance many religions take against suicide and to the greater connectedness religion may give.[64] Muslims, among religious people, appear to have a lower rate of suicide; however the data supporting this is not strong.[65] There does not appear to be a difference in rates of attempted suicide rates.[65] Young women in the Middle East may have higher rates.[66]

Some may take their own lives to escape bullying or prejudice.[67] A history of childhood sexual abuse[68] and time spent in foster care are also risk factors.[69] Sexual abuse is believed to contribute to about 20% of the overall risk.[31]

An evolutionary explanation for suicide is that it may improve inclusive fitness. This may occur if the person dying by suicide cannot have more children and takes resources away from relatives by staying alive. An objection is that deaths by healthy adolescents likely does not increase inclusive fitness. Adaptation to a very different ancestral environment may be maladaptive in the current one.[61][70]

Poverty is associated with the risk of suicide.[71] Increasing relative poverty compared to those around a person increases suicide risk.[72] Over 200,000 farmers in India have died by suicide since 1997 partly due to issues of debt.[73] In China suicide is three times as likely in rural regions as urban ones partly, it is believed, due to financial difficulties in this area of the country.[74]

Media

The media, which includes the Internet, plays an important role.[23] How it presents depiction of suicide may have a negative effect, with high volume, prominent, repetitive coverage glorifying or romanticizing suicide having the most impact.[75] When detailed descriptions of how to kill oneself by a specific means are portrayed, this method of suicide may increase in the population as a whole.[76]

This trigger of 'suicide contagion' or copycat suicide is known as the Werther effect, named after the protagonist in Goethe's The Sorrows of Young Werther who killed himself and then was emulated by many admirers of the book.[77] This risk is greater in adolescents who may romanticize death.[78] It appears that while news media has a significant effect, that of the entertainment media is equivocal.[79][80] The opposite of the Werther effect is the proposed Papageno effect, in which coverage of effective coping mechanisms may have a protective effect. The term is based upon a character in Mozart's opera The Magic Flute, who (fearing the loss of a loved one) had planned to kill himself until his friends helped him out.[77] When media follows recommended reporting guidelines the risk of suicides can be decreased.[75] Getting buy-in from industry, however, can be difficult, especially in the long term.[75]

Rational

Rational suicide is the reasoned taking of one's own life,[81] although some feel that suicide is never logical.[81] The act of taking one's life for the benefit of others is known as altruistic suicide.[82] An example of this is an elder ending his or her life to leave greater amounts of food for the younger people in the community.[82] Suicide in some Inuit cultures has been seen as an act of respect, courage, or wisdom.[83]

A suicide attack is a political action where an attacker carries out violence against others which they understand will result in their own death.[84] Some suicide bombers are motivated by a desire to obtain martyrdoms.[32] Kamikaze missions were carried out as a duty to a higher cause or moral obligation.[83] Murder–suicide is an act of homicide followed within a week by suicide of the person who carried out the act.[85]

Mass suicides are often performed under social pressure where members give up autonomy to a leader.[86] Mass suicides can take place with as few as two people, often referred to as a suicide pact.[87]

In extenuating situations where continuing to live would be intolerable, some people use suicide as a means of escape.[88] Some inmates in Nazi concentration camps are known to have killed themselves by deliberately touching the electrified fences.[89]

Methods

The leading method of suicide varies among countries. The leading methods in different regions include hanging, pesticide poisoning, and firearms.[5] These differences are believed to be in part due to availability of the different methods.[76] A review of 56 countries found that hanging was the most common method in most of the countries,[90] accounting for 53% of the male suicides and 39% of the female suicides.[91]

Worldwide, 30% of suicides are from pesticides. The use of this method, however, varies markedly from 4% in Europe to more than 50% in the Pacific region.[92] It is also common in Latin America due to easy access within the farming populations.[76] In many countries, drug overdoses account for approximately 60% of suicides among women and 30% among men.[93] Many are unplanned and occur during an acute period of ambivalence.[76] The death rate varies by method: firearms 80-90%, drowning 65-80%, hanging 60-85%, car exhaust 40-60%, jumping 35-60%, charcoal burning 40-50%, pesticides 6-75%, and medication overdose 1.5-4%.[76] The most common attempted methods of suicide differ from the most common successful methods; Up to 85% of attempts are via drug overdose in the developed world.[38]

In China, the consumption of pesticides is the most common method.[94] In Japan, self-disembowelment known as seppuku (or hara-kiri) still occurs;[94] however, hanging and jumping are the most common.[95] Jumping to one's death is common in both Hong Kong and Singapore at 50% and 80% respectively.[76] In Switzerland, firearms are the most frequent suicides method in young males, however this method has decreased relatively since guns have become less common.[96][97] In the United States, 57% of suicides involve the use of firearms, with this method being somewhat more common in men than women.[25] The next most common cause was hanging in males and self-poisoning in females.[25] Together these methods comprised about 40% of U.S. suicides.[98]

Pathophysiology

There is no known unifying underlying pathophysiology for either suicide or depression.[25] It is however believed to result from an interplay of behavioral, socio-environmental and psychiatric factors.[76]

Low levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) are both directly associated with suicide[99] and indirectly associated through its role in major depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia and obsessive–compulsive disorder.[100] Post-mortem studies have found reduced levels of BDNF in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, in those with and without psychiatric conditions.[101] Serotonin, a brain neurotransmitter, is believed to be low in those who die by suicide. This is partly based on evidence of increased levels of 5-HT2A receptors found after death.[102] Other evidence includes reduced levels of a breakdown product of serotonin, 5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid, in the cerebral spinal fluid.[103] Direct evidence is however hard to gather.[102] Epigenetics, the study of changes in genetic expression in response to environmental factors which do not alter the underlying DNA, is also believed to play a role in determining suicide risk.[104]

Prevention

Suicide prevention is a term used for the collective efforts to reduce the incidence of suicide through preventative measures. Reducing access to certain methods, such as firearms or toxins reduces the risk.[76][105] Other measures include reducing access to charcoal and barriers on bridges and subway platforms.[76][106] Treatment of drug and alcohol addiction, depression, and those who have attempted suicide in the past may also be effective.[105] Some have proposed reducing access to alcohol as a preventative strategy (such as reducing the number of bars).[24] Although crisis hotlines are common there is little evidence to support or refute their effectiveness.[4][107] In young adults who have recently thought about suicide, cognitive behavioral therapy appears to improve outcomes.[108] Economic development through its ability to reduce poverty may be able to decrease suicide rates.[71] Efforts to increase social connection, especially in elderly males, may be effective.[109] The World Suicide Prevention Day is observed annually on September 10 with the support of the International Association for Suicide Prevention and the World Health Organization.[110]

Screening

There is little data on the effects of screening the general population on the ultimate rate of suicide.[111][112] As there is a high rate of people who test positive via these tools that are not at risk of suicide, there are concerns that screening may significantly increase mental health care resource utilization.[113] Assessing those at high risk however is recommended.[25] Asking about suicidality does not appear to increase the risk.[25]

Mental illness

In those with mental health problems a number of treatments may reduce the risk of suicide. Those who are actively suicidal may be admitted to psychiatric care either voluntarily or involuntarily.[25] Possessions that may be used to harm oneself are typically removed.[38] Some clinicians get patients to sign suicide prevention contracts where they agree to not harm themselves if released.[25] Evidence however does not support a significant effect from this practice.[25] If a person is at low risk, outpatient mental health treatment may be arranged.[38] Short-term hospitalization has not been found to be more effective than community care for improving outcomes in those with borderline personality disorder who are chronically suicidal.[114][115]

There is tentative evidence that psychotherapy, specifically, dialectical behaviour therapy reduces suicidality in adolescents[116] as well as in those with borderline personality disorder.[117] It may also be useful in decreasing suicide attempts in adults at high risk.[118] Evidence however has not found a decrease in completed suicides.[116]

There is controversy around the benefit-versus-harm of antidepressants.[23] In young persons, the newer antidepressants such as SSRIs appear to increase the risk of suicidality from 25 per 1000 to 40 per 1000.[119] In older persons however they might decrease the risk.[25] Lithium appears effective at lowering the risk in those with bipolar disorder and unipolar depression to nearly the same levels as the general population.[120][121]Clozapine may decrease the thoughts of suicide in some people with schizophrenia.[122]

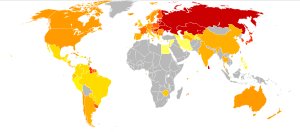

Epidemiology

unknown

<3

3–6

6–9

9–12

12–15

15–18

|

18–21

21–24

24–27

27–30

30–33

>33

|

Approximately 0.5% to 1.4% of people die by suicide, a mortality rate of 11.6 per 100,000 persons per year.[7][25] Suicide resulted in 842,000 deaths in 2013 up from 712,000 deaths in 1990.[6] Rates of suicide have increased by 60% from the 1960s to 2012,[105] with these increases seen primarily in the developing world.[2] Globally, as of 2008/2009, suicide is the tenth leading cause of death.[2] For every suicide that results in death there are between 10 and 40 attempted suicides.[25]

Suicide rates differ significantly between countries and over time.[7] As a percentage of deaths in 2008 it was: Africa 0.5%, South-East Asia 1.9%, Americas 1.2% and Europe 1.4%.[7] Rates per 100,000 were: Australia 8.6, Canada 11.1, China 12.7, India 23.2, United Kingdom 7.6, United States 11.4 and South Korea 28.9.[124][125] It was ranked as the 10th leading cause of death in the United States in 2009 at about 36,000 cases a year,[126] with about 650,000 people seen in emergency departments yearly due to attempting suicide.[25] The country's rate among men in their 50s rose by nearly half in the decade 1999–2010.[127] Lithuania, Japan and Hungary have the highest rates.[7] The countries with the greatest absolute numbers of suicides are China and India, accounting for over half the total.[7] In China, suicide is the 5th leading cause of death.[128]

Gender

no data

< 1

1–5

5–5.8

|

5.8–8.5

8.5–12

12–19

19–22.5

|

22.5–26

26–29.5

29.5–33

33–36.5

|

>36.5

|

In the Western world, males die three to four times more often by means of suicide than do females, although females attempt suicide four times more often.[7][25] This has been attributed to males using more lethal means to end their lives.[129] This difference is even more pronounced in those over the age of 65, with tenfold more males than females dying by suicide.[129] China has one of the highest female suicide rates in the world and is the only country where it is higher than that of men (ratio of 0.9).[7][128] In the Eastern Mediterranean, suicide rates are nearly equivalent between males and females.[7] The highest rate of female suicide is found in South Korea at 22 per 100,000, with high rates in South-East Asia and the Western Pacific generally.[7]

Due in part to social stigmatisation and the resulting depression, people whose gender identity does not align with their assigned sex are at a high risk of suicide.[130]

Age

In many countries the rate of suicide is highest in the middle-aged[131] or elderly.[76] The absolute number of suicides however is greatest in those between 15 and 29 years old due to the number of people in this age group.[7] In the United States it is greatest in caucasian men older than 80 years, even though younger people more frequently attempt suicide.[25] It is the second most common cause of death in adolescents[23] and in young males is second only to accidental death.[131] In young males in the developed world it is the cause of nearly 30% of mortality.[131] In the developing world rates are similar, but it makes up a smaller proportion of overall deaths due to higher rates of death from other types of trauma.[131] In South-East Asia in contrast to other areas of the world, deaths from suicide occur at a greater rate in young females than elderly females.[7]

History

In ancient Athens, a person who committed suicide without the approval of the state was denied the honours of a normal burial. The person would be buried alone, on the outskirts of the city, without a headstone or marker.[132] However, it was deemed to be an acceptable method to deal with military defeat.[133] In Ancient Rome, while suicide was initially permitted, it was later deemed a crime against the state due to its economic costs.[134]

Suicide came to be regarded as a sin in Christian Europe and was condemned at the Council of Arles in 452 as the work of the Devil. In the Middle Ages, the Church had drawn-out discussions as to when the desire for martyrdom was suicidal, as in the case of martyrs of Córdoba. Despite these disputes and occasional official rulings, Catholic doctrine was not entirely settled on the subject of suicide until the later 17th century. A criminal ordinance issued by Louis XIV of France in 1670 was extremely severe, even for the times: the dead person's body was drawn through the streets, face down, and then hung or thrown on a garbage heap. Additionally, all of the person's property was confiscated.[135][136]

Attitudes towards suicide slowly began to shift during the Renaissance. John Donne's work Biathanatos, contained one of the first modern defences of suicide, bringing proof from the conduct of Biblical figures, such as Jesus, Samson and Saul, and presenting arguments on grounds of reason and nature to sanction suicide in certain circumstances.[137]

The secularisation of society that began during The Enlightenment questioned traditional religious attitudes toward suicide and brought a more modern perspective to the issue. David Hume denied that suicide was a crime as it affected no one and was potentially to the advantage of the individual. In his 1777 Essays on Suicide and the Immortality of the Soul he rhetorically asked, "Why should I prolong a miserable existence, because of some frivolous advantage which the public may perhaps receive from me?"[137] A shift in public opinion at large can also be discerned; The Times in 1786 initiated a spirited debate on the motion "Is suicide an act of courage?".[138]

By the 19th-century, the act of suicide had shifted from being viewed as caused by sin to being caused by insanity in Europe.[136] Although suicide remained illegal during this period, it increasingly became the target of satirical comment, such as the Gilbert and Sullivan musical The Mikado that satirised the idea of executing someone who had already killed himself.

By 1879, English law began to distinguish between suicide and homicide, although suicide still resulted in forfeiture of estate.[139] In 1882, the deceased were permitted daylight burial in England[140] and by the middle of the 20th century, suicide had become legal in much of the western world.

Social and culture

Legislation

In most Western countries, suicide is no longer a crime,[141] it however was in most Western European countries from the Middle Ages until at least the 1800s.[139] It remains a criminal offense in most Muslim-majority nations.[65]

In Australia suicide is not a crime.[142] It however is a crime to counsel, incite, or aid and abet another in attempting to die by suicide, and the law explicitly allows any person to use "such force as may reasonably be necessary" to prevent another from taking their own life.[143] The Northern Territory of Australia briefly had legal physician-assisted suicide from 1996 to 1997.[144]

No country in Europe currently considers suicide or attempted suicide to be a crime.[145] England and Wales decriminalized suicide via the Suicide Act 1961 and the Republic of Ireland in 1993.[145] The word "commit" was used in reference to it being illegal, however many organisations have stopped it because of the negative connotation.[146][147]

In India, suicide used to be illegal and surviving family could face legal difficulties.[148] The government of India decided to repeal the law in 2014.[149] In Germany, active euthanasia is illegal and anyone present during suicide may be prosecuted for failure to render aid in an emergency.[150] Switzerland has recently taken steps to legalize assisted suicide for the chronically mentally ill. The high court in Lausanne, in a 2006 ruling, granted an anonymous individual with longstanding psychiatric difficulties the right to end his own life.[151]

In the United States, suicide is not illegal but may be associated with penalties for those who attempt it.[145] Physician-assisted suicide is legal in the state of Washington for people with terminal diseases.[152] Also in Oregon people with terminal diseases may request medications to help end their life.[153]

Canadians who have attempted suicide may be barred from entering the US. US laws allow border guards to deny access to people who have a mental illness, including those with previous suicide attempts.[154][155]

Religious views

In most forms of Christianity, suicide is considered a sin, based mainly on the writings of influential Christian thinkers of the Middle Ages, such as St. Augustine and St. Thomas Aquinas, but suicide was not considered a sin under the Byzantine Christian code of Justinian, for instance.[156][157] In Catholic doctrine, the argument is based on the commandment "Thou shalt not kill" (made applicable under the New Covenant by Jesus in Matthew 19:18), as well as the idea that life is a gift given by God which should not be spurned, and that suicide is against the "natural order" and thus interferes with God's master plan for the world.[158]

However, it is believed that mental illness or grave fear of suffering diminishes the responsibility of the one completing suicide.[159] Counter-arguments include the following: that the sixth commandment is more accurately translated as "thou shalt not murder" (not necessarily applying to the self), that God has given free will to humans, that taking one's own life no more violates God's Law than does curing a disease and that a number of suicides by followers of God are recorded in the Bible with no dire condemnation.[160]

Judaism focuses on the importance of valuing this life, and as such, suicide is tantamount to denying God's goodness in the world. Despite this, under extreme circumstances when there has seemed no choice but to either be killed or forced to betray their religion, Jews have committed individual suicide or mass suicide (see Masada, First French persecution of the Jews, and York Castle for examples) and as a grim reminder there is even a prayer in the Jewish liturgy for "when the knife is at the throat", for those dying "to sanctify God's Name" (see Martyrdom). These acts have received mixed responses by Jewish authorities, regarded by some as examples of heroic martyrdom, while others state that it was wrong for them to take their own lives in anticipation of martyrdom.[161]

Islamic religious views are against suicide.[65] The Qu'ran forbids it by stating "do not kill or destroy yourself".[162] The hadiths additionally state individual suicide to be unlawful and a sin.[65] There is additionally often stigma associated with suicide in Islamic countries.[162]

In Hinduism, suicide is generally frowned upon and is considered equally sinful as murdering another in contemporary Hindu society. Hindu Scriptures state that one who dies by suicide will become part of the spirit world, wandering earth until the time one would have otherwise died, had one not taken ones own life.[163] However, Hinduism accepts a man's right to end one's life through the non-violent practice of fasting to death, termed Prayopavesa.[164] But Prayopavesa is strictly restricted to people who have no desire or ambition left, and no responsibilities remaining in this life.[164] Jainism has a similar practice named Santhara. Sati, or self-immolation by widows, was prevalent in Hindu society during the Middle Ages.[165]

Philosophy

A number of questions are raised within the philosophy of suicide, included what constitutes suicide, whether or not suicide can be a rational choice, and the moral permissibility of suicide.[166] Arguments as to acceptability of suicide in moral or social terms range from the position that the act is inherently immoral and unacceptable under any circumstances to a regard for suicide as a sacrosanct right of anyone who believes they have rationally and conscientiously come to the decision to end their own lives, even if they are young and healthy.

Opponents to suicide include Christian philosophers such as Augustine of Hippo, Thomas Aquinas,[166] Immanuel Kant[167] and, arguably, John Stuart Mill – Mill's focus on the importance of liberty and autonomy meant that he rejected choices which would prevent a person from making future autonomous decisions.[168] Others view suicide as a legitimate matter of personal choice. Supporters of this position maintain that no one should be forced to suffer against their will, particularly from conditions such as incurable disease, mental illness, and old age, with no possibility of improvement. They reject the belief that suicide is always irrational, arguing instead that it can be a valid last resort for those enduring major pain or trauma.[169] A stronger stance would argue that people should be allowed to autonomously choose to die regardless of whether they are suffering. Notable supporters of this school of thought include Scottish empiricist David Hume[166] and American bioethicist Jacob Appel.[151][170]

Advocacy

Advocacy of suicide has occurred in many cultures and subcultures. The Japanese military during World War II encouraged and glorified kamikaze attacks, which were suicide attacks by military aviators from the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific theatre of World War II. Japanese society as a whole has been described as "suicide tolerant"[172] (see Suicide in Japan).

Internet searches for information on suicide return webpages that 10-30% of the time encourage or facilitate suicide attempts. There is some concern that such sites may push those predisposed over the edge. Some people form suicide pacts online, either with pre-existing friends or people they have recently encountered in chat rooms or message boards. The Internet, however, may also help prevent suicide by providing a social group for those who are isolated.[173]

Locations

Some landmarks have become known for high levels of suicide attempts.[174] These include San Francisco's Golden Gate Bridge, Japan's Aokigahara Forest,[175] England's Beachy Head[174] and Toronto's Bloor Street Viaduct.[176]

As of 2010, the Golden Gate Bridge has had more than 1,300 die by suicide by jumping since its construction in 1937.[177] Many locations where suicide is common have constructed barriers to prevent it;[178] this includes the Luminous Veil in Toronto,[176] the Eiffel Tower in Paris and Empire State Building in New York City.[178] As of 2011, a barrier is being constructed for the Golden Gate Bridge.[179] They appear to be generally effective.[179]

Notable cases

An example of mass suicide is the 1978 Jonestown killings/suicide in which 909 members of the Peoples Temple, an American religious group led by Jim Jones, ended their lives by drinking grape Flavor Aid laced with cyanide.[180][181][182] Thousands of Japanese civilians took their own lives in the last days of the Battle of Saipan in 1944, some jumping from "Suicide Cliff" and "Banzai Cliff".[183]

The 1981 hunger strikes, led by Bobby Sands, resulted in 10 deaths. The cause of death was recorded by the coroner as "starvation, self-imposed" rather than suicide; this was modified to simply "starvation" on the death certificates after protest from the dead strikers' families.[184] During World War II, Erwin Rommel was found to have foreknowledge of the July 20 Plot on Hitler's life; he was threatened with public trial, execution and reprisals on his family unless he took his own life.[185]

Other species

As suicide requires a willful attempt to die, some feel it therefore cannot be said to occur in non-human animals.[133] Suicidal behavior has been observed in salmonella seeking to overcome competing bacteria by triggering an immune system response against them.[186] Suicidal defenses by workers are also noted in the Brazilian ant Forelius pusillus, where a small group of ants leaves the security of the nest after sealing the entrance from the outside each evening.[187]

Pea aphids, when threatened by a ladybug, can explode themselves, scattering and protecting their brethren and sometimes even killing the ladybug.[188] Some species of termites have soldiers that explode, covering their enemies with sticky goo.[189][190]

There have been anecdotal reports of dogs, horses and dolphins killing themselves, though with little conclusive evidence.[191] There has been little scientific study of animal suicide.[192]

Notes

- ↑ Paris, J (June 2002). "Chronic suicidality among patients with borderline personality disorder". Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.) 53 (6): 738–42. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.6.738. PMID 12045312.

- 1 2 3 4 Hawton K, van Heeringen K (April 2009). "Suicide". Lancet 373 (9672): 1372–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60372-X. PMID 19376453.

- ↑ Bottino, SM; Bottino, CM; Regina, CG; Correia, AV; Ribeiro, WS (March 2015). "Cyberbullying and adolescent mental health: systematic review.". Cadernos de saude publica 31 (3): 463–75. doi:10.1590/0102-311x00036114. PMID 25859714.

- 1 2 Sakinofsky, I (June 2007). "The current evidence base for the clinical care of suicidal patients: strengths and weaknesses". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 52 (6 Suppl 1): 7S–20S. PMID 17824349.

- 1 2 Ajdacic-Gross V, Weiss MG, Ring M, et al. (September 2008). "Methods of suicide: international suicide patterns derived from the WHO mortality database". Bull. World Health Organ. 86 (9): 726–32. doi:10.2471/BLT.07.043489. PMC 2649482. PMID 18797649.

- 1 2 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.". Lancet 385: 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Värnik, P (March 2012). "Suicide in the world". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 9 (3): 760–71. doi:10.3390/ijerph9030760. PMC 3367275. PMID 22690161.

- ↑ Meier, Marshall B. Clinard, Robert F. (2008). Sociology of deviant behavior (14th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-495-81167-1.

- ↑ Bertolote JM, Fleischmann A (October 2002). "Suicide and psychiatric diagnosis: a worldwide perspective". World Psychiatry 1 (3): 181–5. PMC 1489848. PMID 16946849.

- ↑ "Indian woman commits sati suicide". Bbc.co.uk. 2002-08-07. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ Aggarwal, N (2009). "Rethinking suicide bombing". Crisis 30 (2): 94–7. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.30.2.94. PMID 19525169.

- ↑ Stedman's medical dictionary (28th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7817-3390-8.

- 1 2 Krug, Etienne (2002). World Report on Violence and Health (Vol. 1). Genève: World Health Organization. p. 185. ISBN 978-92-4-154561-7.

- 1 2 Gullota, edited by Thomas P.; Bloom, Martin (2002). The encyclopedia of primary prevention and health promotion. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum. p. 1112. ISBN 978-0-306-47296-1.

- ↑ Ball, P. Bonny (2005). "The Power of words". Canadian Association of Suicide Prevention. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ↑ Beck, A.T.; Resnik, H.L.P. & Lettieri, D.J, eds. (1974). "Development of suicidal intent scales". The prediction of suicide. Bowie, MD: Charles Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0913486139.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide" (PDF). National Institute of Mental Health. 2001. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "Reporting Suicide and Self Harm". Time To Change. 2008. Retrieved 2 Jan 2016.

- ↑ "Media Guidelines for Reporting Suicide" (PDF). 2013. Retrieved 2 Jan 2016.

- ↑ Olson, Robert (2011). "Suicide and Language". Centre for Suicide Prevention. InfoExchange (3): 4. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ Beaton, Susan; Forster, Peter; Maple, Myfanwy (February 2013). "Suicide and Language: Why we Shouldn't Use the 'C' Word". In Psych (Melbourne: Australian Psychological Society) 35 (1): 30–31.

- ↑ Karch, DL; Logan, J; Patel, N; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC) (Aug 26, 2011). "Surveillance for violent deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2008". Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002) 60 (10): 1–49. PMID 21866088. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Hawton, K; Saunders, KE; O'Connor, RC (Jun 23, 2012). "Self-harm and suicide in adolescents". Lancet 379 (9834): 2373–82. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5. PMID 22726518.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Vijayakumar, L; Kumar, MS; Vijayakumar, V (May 2011). "Substance use and suicide". Current opinion in psychiatry 24 (3): 197–202. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283459242. PMID 21430536.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Chang, B; Gitlin, D; Patel, R (September 2011). "The depressed patient and suicidal patient in the emergency department: evidence-based management and treatment strategies". Emergency medicine practice 13 (9): 1–23; quiz 23–4. PMID 22164363.

- ↑ Simpson, G; Tate, R (December 2007). "Suicidality in people surviving a traumatic brain injury: prevalence, risk factors and implications for clinical management". Brain injury : [BI] 21 (13–14): 1335–51. doi:10.1080/02699050701785542. PMID 18066936.

- 1 2 Miller, M; Azrael, D; Barber, C (April 2012). "Suicide mortality in the United States: the importance of attending to method in understanding population-level disparities in the burden of suicide". Annual review of public health 33: 393–408. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124636. PMID 22224886.

- ↑ Qin P, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB (April 2003). "Suicide risk in relation to socioeconomic, demographic, psychiatric, and familial factors: a national register-based study of all suicides in Denmark, 1981–1997". Am J Psychiatry 160 (4): 765–72. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.4.765. PMID 12668367.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC) (May 3, 2013). "Suicide among adults aged 35-64 years--United States, 1999-2010.". MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 62 (17): 321–5. PMID 23636024.

- ↑ Gilliland, Richard K. James, Burl E. (2012-05-08). Crisis intervention strategies (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-111-18677-7.

- 1 2 Brent, DA; Melhem, N (June 2008). "Familial transmission of suicidal behavior". The Psychiatric clinics of North America 31 (2): 157–77. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2008.02.001. PMC 2440417. PMID 18439442.

- 1 2 Rozanov, V; Carli, V (July 2012). "Suicide among war veterans". International journal of environmental research and public health 9 (7): 2504–19. doi:10.3390/ijerph9072504. PMC 3407917. PMID 22851956.

- 1 2 University of Manchester Centre for Mental Health and Risk. "The National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness" (PDF). Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chehil, Stan Kutcher, Sonia (2012). Suicide Risk Management A Manual for Health Professionals. (2nd ed.). Chicester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 30–33. ISBN 978-1-119-95311-1.

- ↑ Pompili, M; Girardi, P; Ruberto, A; Tatarelli, R (2005). "Suicide in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis.". Nordic journal of psychiatry 59 (5): 319–24. doi:10.1080/08039480500320025. PMID 16757458.

- ↑ Bertolote, JM; Fleischmann, A; De Leo, D; Wasserman, D (2004). "Psychiatric diagnoses and suicide: revisiting the evidence". Crisis 25 (4): 147–55. doi:10.1027/0227-5910.25.4.147. PMID 15580849.

- ↑ van Os J, Kapur S (August 2009). "Schizophrenia" (PDF). Lancet 374 (9690): 635–45. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60995-8. PMID 19700006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tintinalli, Judith E. (2010). Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide (Emergency Medicine (Tintinalli)). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies. pp. 1940–1946. ISBN 0-07-148480-9.

- 1 2 Greydanus, DE; Shek, D (September 2009). "Deliberate self-harm and suicide in adolescents". The Keio journal of medicine 58 (3): 144–51. doi:10.2302/kjm.58.144. PMID 19826208.

- 1 2 Pirkis, J; Burgess, P (December 1998). "Suicide and recency of health care contacts. A systematic review". The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science 173 (6): 462–74. doi:10.1192/bjp.173.6.462. PMID 9926074.

- ↑ Luoma, JB; Martin, CE; Pearson, JL (June 2002). "Contact with mental health and primary care providers before suicide: a review of the evidence". The American Journal of Psychiatry 159 (6): 909–16. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.909. PMID 12042175.

- ↑ Sharma, Tarang; Guski, Louise Schow; Freund, Nanna; Gøtzsche, Peter C (27 January 2016). "Suicidality and aggression during antidepressant treatment: systematic review and meta-analyses based on clinical study reports". BMJ: i65. doi:10.1136/bmj.i65.

- ↑ Perrotto, Jerome D. Levin, Joseph Culkin, Richard S. (2001). Introduction to chemical dependency counseling. Northvale, N.J.: Jason Aronson. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-0-7657-0289-0.

- 1 2 Fadem, Barbara (2004). Behavioral science in medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 217. ISBN 978-0-7817-3669-5.

- ↑ Youssef NA, Rich CL (2008). "Does acute treatment with sedatives/hypnotics for anxiety in depressed patients affect suicide risk? A literature review". Ann Clin Psychiatry 20 (3): 157–69. doi:10.1080/10401230802177698. PMID 18633742.

- 1 2 Sher, L (January 2006). "Alcohol consumption and suicide". QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians 99 (1): 57–61. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hci146. PMID 16287907.

- ↑ Darke S, Ross J (November 2002). "Suicide among heroin users: rates, risk factors and methods". Addiction 97 (11): 1383–94. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00214.x. PMID 12410779.

- ↑ Sher L (2007). "Functional magnetic resonance imaging in studies of the neurobiology of suicidal behavior in adolescents with alcohol use disorders". Int J Adolesc Med Health 19 (1): 11–8. doi:10.1515/ijamh.2007.19.1.11. PMID 17458319.

- ↑ Darke, S; Kaye, S; McKetin, R; Duflou, J (May 2008). "Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use". Drug and alcohol review 27 (3): 253–62. doi:10.1080/09595230801923702. PMID 18368606.

- ↑ Jr, Frank J. Ayd, (2000). Lexicon of psychiatry, neurology, and the neurosciences (2nd ed.). Philadelphia [u.a.]: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-7817-2468-5.

- 1 2 Hughes, JR (Dec 1, 2008). "Smoking and suicide: a brief overview". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 98 (3): 169–78. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.06.003. PMC 2585177. PMID 18676099.

- ↑ Pallanti, Stefano; Rossi, Nicolò Baldini; Hollander, Eric (2006). "11. Pathological Gambling". In Hollander, Eric; Stein, Dan J. Clinical manual of impulse-control disorders. American Psychiatric Pub. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-58562-136-1.

- 1 2 Oliveira, MP; Silveira, DX; Silva, MT (June 2008). "Pathological gambling and its consequences for public health". Revista de saude publica 42 (3): 542–9. doi:10.1590/S0034-89102008005000026. PMID 18461253.

- ↑ Hansen, M; Rossow, I (Jan 17, 2008). "Gambling and suicidal behaviour". Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening : tidsskrift for praktisk medicin, ny raekke 128 (2): 174–6. PMID 18202728.

- ↑ Manthorpe, J; Iliffe, S (December 2010). "Suicide in later life: public health and practitioner perspectives". International journal of geriatric psychiatry 25 (12): 1230–8. doi:10.1002/gps.2473. PMID 20104515.

- ↑ Simpson GK, Tate RL (August 2007). "Preventing suicide after traumatic brain injury: implications for general practice". Med. J. Aust. 187 (4): 229–32. PMID 17708726.

- 1 2 Anguiano, L; Mayer, DK; Piven, ML; Rosenstein, D (Jul–Aug 2012). "A literature review of suicide in cancer patients". Cancer nursing 35 (4): E14–26. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822fc76c. PMID 21946906.

- ↑ Yip, edited by Paul S.F. (2008). Suicide in Asia : causes and prevention. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-962-209-943-2.

- ↑ Ribeiro, JD; Pease, JL; Gutierrez, PM; Silva, C; Bernert, RA; Rudd, MD; Joiner TE, Jr (February 2012). "Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military". Journal of Affective Disorders 136 (3): 743–50. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049. PMID 22032872.

- ↑ Bernert, RA; Joiner TE, Jr; Cukrowicz, KC; Schmidt, NB; Krakow, B (September 2005). "Suicidality and sleep disturbances". Sleep 28 (9): 1135–41. PMID 16268383. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - 1 2 Joiner TE, Jr; Brown, JS; Wingate, LR (2005). "The psychology and neurobiology of suicidal behavior". Annual Review of Psychology 56: 287–314. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070320. PMID 15709937.

- ↑ Van Orden, K; Conwell, Y (June 2011). "Suicides in late life". Current psychiatry reports 13 (3): 234–41. doi:10.1007/s11920-011-0193-3. PMC 3085020. PMID 21369952.

- ↑ Stein, edited by George; Wilkinson, Greg (2007). Seminars in general adult psychiatry (2. ed.). London: Gaskell. p. 144. ISBN 9781904671442.

- 1 2 Koenig, HG (May 2009). "Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review" (PDF). Canadian journal of psychiatry. Revue canadienne de psychiatrie 54 (5): 283–91. PMID 19497160.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lester, D (2006). "Suicide and islam". Archives of suicide research : official journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research 10 (1): 77–97. doi:10.1080/13811110500318489. PMID 16287698.

- ↑ Rezaeian, M (2010). "Suicide among young Middle Eastern Muslim females.". Crisis 31 (1): 36–42. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000005. PMID 20197256.

- ↑ Cox, William T. L.; Abramson, Lyn Y.; Devine, Patricia G.; Hollon, Steven D. (2012). "Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Depression: The Integrated Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science 7 (5): 427–449. doi:10.1177/1745691612455204.

- ↑ Wegman, HL; Stetler, C (October 2009). "A meta-analytic review of the effects of childhood abuse on medical outcomes in adulthood". Psychosomatic Medicine 71 (8): 805–12. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bb2b46. PMID 19779142.

- ↑ Oswald, SH; Heil, K; Goldbeck, L (June 2010). "History of maltreatment and mental health problems in foster children: a review of the literature". Journal of pediatric psychology 35 (5): 462–72. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsp114. PMID 20007747.

- ↑ Confer, Jaime C.; Easton, Judith A.; Fleischman, Diana S.; Goetz, Cari D.; Lewis, David M. G.; Perilloux, Carin; Buss, David M. (1 January 2010). "Evolutionary psychology: Controversies, questions, prospects, and limitations". American Psychologist 65 (2): 110–126. doi:10.1037/a0018413. PMID 20141266.

- 1 2 Stark, CR; Riordan, V; O'Connor, R (2011). "A conceptual model of suicide in rural areas". Rural and remote health 11 (2): 1622. PMID 21702640.

- ↑ Daly, Mary (Sep 2012). "Relative Status and Well-Being: Evidence from U.S. Suicide Deaths" (PDF). Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper Series.

- ↑ Lerner, George (Jan 5, 2010). "Activist: Farmer suicides in India linked to debt, globalization". CNN World. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- ↑ Law, S; Liu, P (February 2008). "Suicide in China: unique demographic patterns and relationship to depressive disorder". Current psychiatry reports 10 (1): 80–6. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0014-5. PMID 18269899.

- 1 2 3 Bohanna, I; Wang, X (2012). "Media guidelines for the responsible reporting of suicide: a review of effectiveness". Crisis 33 (4): 190–8. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000137. PMID 22713977.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Yip, PS; Caine, E; Yousuf, S; Chang, SS; Wu, KC; Chen, YY (Jun 23, 2012). "Means restriction for suicide prevention". Lancet 379 (9834): 2393–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60521-2. PMID 22726520.

- 1 2 Sisask, M; Värnik, A (January 2012). "Media roles in suicide prevention: a systematic review". International journal of environmental research and public health 9 (1): 123–38. doi:10.3390/ijerph9010123. PMC 3315075. PMID 22470283.

- ↑ Stack S (April 2005). "Suicide in the media: a quantitative review of studies based on non-fictional stories". Suicide Life Threat Behav 35 (2): 121–33. doi:10.1521/suli.35.2.121.62877. PMID 15843330.

- ↑ Pirkis J (July 2009). "Suicide and the media". Psychiatry 8 (7): 269–271. doi:10.1016/j.mppsy.2009.04.009.

- ↑ Shrivastava, Amresh; Kimbrell,, Megan; editors, David Lester, (2012). Suicide from a global perspective : psychosocial approaches. New York: Nova Science Publishers. pp. 115–118. ISBN 978-1-61470-965-7.

- 1 2 Loue, Sana (2008). Encyclopedia of aging and public health : with 19 tables. New York, NY: Springer. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-387-33753-1.

- 1 2 Moody, Harry R. (2010). Aging : concepts and controversies (6th ed.). Los Angeles: Pine Forge Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-4129-6966-6.

- 1 2 Hales, edited by Robert I. Simon, Robert E. (2012). The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of suicide assessment and management (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Pub. p. 714. ISBN 978-1-58562-414-0.

- ↑ editor, Tarek Sobh, (2010). Innovations and advances in computer sciences and engineering (Online-Ausg. ed.). Dordrecht: Springer Verlag. p. 503. ISBN 978-90-481-3658-2.

- ↑ Eliason, S (2009). "Murder-suicide: a review of the recent literature". The journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 37 (3): 371–6. PMID 19767502.

- ↑ Smith, William Kornblum in collaboration with Carolyn D. (2011-01-31). Sociology in a changing world (9e [9th ed]. ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-111-30157-6.

- ↑ Campbell, Robert Jean (2004). Campbell's psychiatric dictionary (8th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 636. ISBN 978-0-19-515221-0.

- ↑ Veatch, ed. by Robert M. (1997). Medical ethics (2. ed.). Sudbury, Mass. [u.a.]: Jones and Bartlett. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-86720-974-7.

- ↑ Gutman, Yisrael; editors, Michael Berenbaum, (1998). Anatomy of the Auschwitz death camp (1st pbk. ed.). Bloomington: Publ. in association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C. by Indiana University Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Ajdacic-Gross, Vladeta, et al. "Methods of suicide: international suicide patterns derived from the WHO mortality database" PDF (267 KB). Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86 (9): 726–732. September 2008. Accessed 2 August 2011. Archived 2 August 2011. See html version. The data can be seen here

- ↑ O'Connor, Rory C.; Platt, Stephen; Gordon, Jacki, eds. (1 June 2011). International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy and Practice. John Wiley and Sons. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-119-99856-3.

- ↑ Gunnell D., Eddleston M., Phillips M.R., Konradsen F. (2007). "The global distribution of fatal pesticide self-poisoning: systematic review". BMC Public Health 7: 357. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-357. PMC 2262093. PMID 18154668.

- ↑ Geddes, John; Price, Jonathan; Gelder, Rebecca McKnight; with Michael; Mayou, Richard (2012-01-05). Psychiatry (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-19-923396-0.

- 1 2 Krug, Etienne (2002). World Report on Violence and Health, Volume 1. Genève: World Health Organization. p. 196. ISBN 978-92-4-154561-7.

- ↑ Yoshioka, E; Hanley, SJ; Kawanishi, Y; Saijo, Y (6 November 2014). "Time trends in method-specific suicide rates in Japan, 1990-2011.". Epidemiology and psychiatric sciences: 1–11. doi:10.1017/S2045796014000675. PMID 25373686.

- ↑ Reisch, T; Steffen, T; Habenstein, A; Tschacher, W (September 2013). "Change in suicide rates in Switzerland before and after firearm restriction resulting from the 2003 "Army XXI" reform.". The American Journal of Psychiatry 170 (9): 977–84. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12091256. PMID 23897090.

- ↑ Eshun, edited by Sussie; Gurung, Regan A.R. (2009). Culture and mental health sociocultural influences, theory, and practice. Chichester, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 301. ISBN 978-1-4443-0581-4.

- ↑ "U.S. Suicide Statistics (2005)". Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ Pjevac, M; Pregelj, P (October 2012). "Neurobiology of suicidal behaviour". Psychiatria Danubina. 24 Suppl 3: S336–41. PMID 23114813.

- ↑ Sher, L (2011). "The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the pathophysiology of adolescent suicidal behavior". International journal of adolescent medicine and health 23 (3): 181–5. doi:10.1515/ijamh.2011.041. PMID 22191181.

- ↑ Sher, L (May 2011). "Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and suicidal behavior". QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians 104 (5): 455–8. doi:10.1093/qjmed/hcq207. PMID 21051476.

- 1 2 Dwivedi, Yogesh (2012). The neurobiological basis of suicide. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis/CRC Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-1-4398-3881-5.

- ↑ Stein, edited by George; Wilkinson, Greg (2007). Seminars in general adult psychiatry (2. ed.). London: Gaskell. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-904671-44-2.

- ↑ Autry, AE; Monteggia, LM (Nov 1, 2009). "Epigenetics in suicide and depression". Biological Psychiatry 66 (9): 812–3. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.033. PMC 2770810. PMID 19833253.

- 1 2 3 "Suicide prevention". WHO Sites: Mental Health. World Health Organization. Aug 31, 2012. Retrieved 2013-01-13.

- ↑ Cox, GR; Owens, C; Robinson, J; Nicholas, A; Lockley, A; Williamson, M; Cheung, YT; Pirkis, J (Mar 9, 2013). "Interventions to reduce suicides at suicide hotspots: a systematic review". BMC Public Health 13: 214. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-214. PMC 3606606. PMID 23496989.

- ↑ "Suicide". The United States Surgeon General. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ↑ Robinson, J; Hetrick, SE; Martin, C (January 2011). "Preventing suicide in young people: systematic review". The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry 45 (1): 3–26. doi:10.3109/00048674.2010.511147. PMID 21174502.

- ↑ Fässberg, MM; van Orden, KA; Duberstein, P; Erlangsen, A; Lapierre, S; Bodner, E; Canetto, SS; De Leo, D; Szanto, K; Waern, M (March 2012). "A systematic review of social factors and suicidal behavior in older adulthood". International journal of environmental research and public health 9 (3): 722–45. doi:10.3390/ijerph9030722. PMC 3367273. PMID 22690159. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ "World Suicide Prevention Day -10 September, 2013". IASP. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ↑ Williams, SB; O'Connor, EA; Eder, M; Whitlock, EP (April 2009). "Screening for child and adolescent depression in primary care settings: a systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force". Pediatrics 123 (4): e716–35. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2415. PMID 19336361.

- ↑ LeFevre, ML; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (May 20, 2014). "Screening for suicide risk in adolescents, adults, and older adults in primary care: u.s. Preventive services task force recommendation statement.". Annals of Internal Medicine 160 (10): 719–26. doi:10.7326/M14-0589. PMID 24842417. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Horowitz, LM; Ballard, ED; Pao, M (October 2009). "Suicide screening in schools, primary care and emergency departments". Current Opinion in Pediatrics 21 (5): 620–7. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283307a89. PMC 2879582. PMID 19617829.

- ↑ Paris, J (June 2004). "Is hospitalization useful for suicidal patients with borderline personality disorder?". Journal of personality disorders 18 (3): 240–7. doi:10.1521/pedi.18.3.240.35443. PMID 15237044.

- ↑ Goodman, M; Roiff, T; Oakes, AH; Paris, J (February 2012). "Suicidal risk and management in borderline personality disorder". Current psychiatry reports 14 (1): 79–85. doi:10.1007/s11920-011-0249-4. PMID 22113831.

- 1 2 Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, (CADTH) (2010). "Dialectical behaviour therapy in adolescents for suicide prevention: systematic review of clinical-effectiveness". CADTH technology overviews 1 (1): e0104. PMC 3411135. PMID 22977392.

- ↑ Stoffers, JM; Völlm, BA; Rücker, G; Timmer, A; Huband, N; Lieb, K (Aug 15, 2012). Lieb, Klaus, ed. "Psychological therapies for people with borderline personality disorder". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 8: CD005652. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005652.pub2. PMID 22895952.

- ↑ Elizabeth O'Connor; Bradley N. Gaynes; Brittany U. Burda; Clara Soh; Evelyn P. Whitlock (April 2013). "Screening for and Treatment of Suicide Risk Relevant to Primary Care: A Systematic Review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force". Annals of Internal Medicine 158 (10): 741–54. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00642. PMID 23609101.

- ↑ Hetrick, SE; McKenzie, JE; Cox, GR; Simmons, MB; Merry, SN (Nov 14, 2012). Hetrick, Sarah E, ed. "Newer generation antidepressants for depressive disorders in children and adolescents". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 11: CD004851. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004851.pub3. PMID 23152227.

- ↑ Baldessarini, RJ; Tondo, L; Hennen, J (2003). "Lithium treatment and suicide risk in major affective disorders: update and new findings". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 64 Suppl 5: 44–52. PMID 12720484.

- ↑ Cipriani, A.; Hawton, K.; Stockton, S.; Geddes, J. R. (27 June 2013). "Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis". BMJ 346 (jun27 4): f3646–f3646. doi:10.1136/bmj.f3646. PMID 23814104.

- ↑ Wagstaff, A; Perry, C (2003). "Clozapine: in prevention of suicide in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.". CNS Drugs 17 (4): 273–80; discussion 281–3. doi:10.2165/00023210-200317040-00004. PMID 12665398.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009.

- ↑ "Deaths estimates for 2008 by cause for WHO Member States". World Health Organization. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "Suicide rates Data by country". who.int. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ↑ Haney, EM; O'Neil, ME; Carson, S; Low, A; Peterson, K; Denneson, LM; Oleksiewicz, C; Kansagara, D (March 2012). "Suicide Risk Factors and Risk Assessment Tools: A Systematic Review". PMID 22574340.

- ↑ "CDC finds suicide rates among middle-aged adults increased from 1999 to 2010". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. May 2, 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2013.

- 1 2 Weiyuan, C (December 2009). "Women and suicide in rural China". Bulletin of the World Health Organization 87 (12): 888–9. doi:10.2471/BLT.09.011209. PMC 2789367. PMID 20454475.

- 1 2 David Sue, Derald Wing Sue, Stanley Sue, Diane Sue (2012-01-01). Understanding abnormal behavior (Tenth ed., [student ed.] ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. p. 255. ISBN 978-1-111-83459-3.

- ↑ http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/ntds_full.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 Pitman, A; Krysinska, K; Osborn, D; King, M (Jun 23, 2012). "Suicide in young men". The Lancet 379 (9834): 2383–92. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60731-4. PMID 22726519.

- ↑ Szasz, Thomas (1999). Fatal freedom : the ethics and politics of suicide. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-275-96646-1.

- 1 2 Maris, Ronald (2000). Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. New York [u.a.]: Guilford Press. pp. 97–103. ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- ↑ Dickinson, Michael R. Leming, George E. (2010-09-02). Understanding dying, death, and bereavement (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-495-81018-6.

- ↑ W. S. F. Pickering; Geoffrey Walford (2000). Durkheim's Suicide : a century of research and debate (1. publ. ed.). London [u.a.]: Routledge. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-415-20582-5.

- 1 2 Maris, Ronald (2000). Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. New York [u.a.]: Guilford Press. p. 540. ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- 1 2 "Suicide". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ Paula R. Backscheider, Catherine Ingrassia (2008). A Companion to the Eighteenth-Century English Novel and Culture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 530. ISBN 9781405154505.

- 1 2 Paperno, Irina (1997). Suicide as a cultural institution in Dostoevsky's Russia. Ithaca: Cornell university press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-8014-8425-4.

- ↑ Norman St. John-Stevas (2002). Life, Death and the Law: Law and Christian Morals in England and the United States. Beard Books. p. 233. ISBN 9781587981135.

- ↑ White, Tony (2010). Working with suicidal individuals : a guide to providing understanding, assessment and support. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-84905-115-6.

- ↑ al.], David Lanham ... [et (2006). Criminal laws in Australia. Annandale, N.S.W.: The Federation Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-86287-558-6.

- ↑ Duffy, Michael Costa, Mark (1991). Labor, prosperity and the nineties : beyond the bonsai economy (2nd ed.). Sydney: Federation Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-1-86287-060-4.

- ↑ Quill, Constance E. Putnam ; foreword by Timothy E. (2002). Hospice or hemlock? : searching for heroic compassion. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-89789-921-5.

- 1 2 3 McLaughlin, Columba (2007). Suicide-related behaviour understanding, caring and therapeutic responses. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-470-51241-8.

- ↑ Holt, Gerry."When suicide was illegal". BBC News. 3 August 2011. Accessed 11 August 2011.

- ↑ "Guardian & Observer style guide". Guardian website. The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ↑ Srivastava, editors, Nitish Dogra, Sangeet (2012-01-01). Climate change and disease dynamics in India. New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute. p. 256. ISBN 978-81-7993-412-8.

- ↑ "Govt decides to repeal Section 309 from IPC; attempt to suicide no longer a crime". Zee News. December 10, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2014.

- ↑ "German politician Roger Kusch helped elderly woman to die". Times Online. July 2, 2008.

- 1 2 Appel, JM (May 2007). "A Suicide Right for the Mentally Ill? A Swiss Case Opens a New Debate". Hastings Center Report 37 (3): 21–23. doi:10.1353/hcr.2007.0035. PMID 17649899.

- ↑ "Chapter 70.245 RCW, The Washington death with dignity act". Washington State Legislature.

- ↑ "Oregon Revised Statute - 127.800 s.1.01. Definitions". Oregon State Legislature.

- ↑ "CBCNews.ca Mobile". Cbc.ca. 1999-02-01. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ Claude Adams (April 15, 2014). "US border suicide profiling must stop: Report". globalnews.ca. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ↑ Dr. Ronald Roth, D.Acu. "Suicide & Euthanasia – a Biblical Perspective". Acu-cell.com. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Norman N. Holland, Literary Suicides: A Question of Style". Clas.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – PART 3 SECTION 2 CHAPTER 2 ARTICLE 5". Scborromeo.org. 1941-06-01. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church – PART 3 SECTION 2 CHAPTER 2 ARTICLE 5". Scborromeo.org. 1941-06-01. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "The Bible and Suicide". Religioustolerance.org. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Euthanasia and Judaism: Jewish Views of Euthanasia and Suicide". ReligionFacts.com. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- 1 2 Gearing, RE; Lizardi, D (September 2009). "Religion and suicide.". Journal of religion and health 48 (3): 332–41. doi:10.1007/s10943-008-9181-2. PMID 19639421.

- ↑ Hindu Website. Hinduism and suicide

- 1 2 "Hinduism – Euthanasia and Suicide". BBC. 2009-08-25.

- ↑ BBC News, "India wife dies on husband's pyre", Aug. 22, 2006.

- 1 2 3 "Suicide (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Kant, Immanuel. (1785) Kant: The Metaphysics of Morals, M. Gregor (trans.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-521-56673-5. p177.

- ↑ Safranek John P (1998). "Autonomy and Assisted Suicide: The Execution of Freedom". The Hastings Center Report 28 (4): 33. doi:10.2307/3528611.

- ↑ Raymond Whiting: A natural right to die: twenty-three centuries of debate, pp. 13–17; Praeger (2001) ISBN 0-313-31474-8

- ↑ Wesley J. Smith, Death on Demand: The assisted-suicide movement sheds its fig leaf, The Weekly Standard, June 5, 2007

- ↑ "The Suicide". The Walters Art Museum.

- ↑ Ozawa-de Silva, C (December 2008). "Too lonely to die alone: internet suicide pacts and existential suffering in Japan". Culture, medicine and psychiatry 32 (4): 516–51. doi:10.1007/s11013-008-9108-0. PMID 18800195.

- ↑ Durkee, T; Hadlaczky, G; Westerlund, M; Carli, V (October 2011). "Internet pathways in suicidality: a review of the evidence". International journal of environmental research and public health 8 (10): 3938–52. doi:10.3390/ijerph8103938. PMC 3210590. PMID 22073021.

- 1 2 Robinson, edited by David Picard, Mike (2012-11-28). Emotion in motion : tourism, affect and transformation. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4094-2133-7.

- ↑ Robinson, ed. by Peter; Heitmann, Sine; Dieke, Peter (2010). Research themes for tourism. Oxfordshire [etc.]: CABI. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-84593-684-6.

- 1 2 Dennis, Richard (2008). Cities in modernity : representations and productions of metropolitan space, 1840 – 1930 (Repr. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-46841-1.

- ↑ McDougall, Tim; Armstrong, Marie; Trainor, Gemma (2010). Helping children and young people who self-harm : an introduction to self-harming and suicidal behaviours for health professionals. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-415-49913-2.

- 1 2 Bateson, John (2008). Building hope : leadership in the nonprofit world. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-313-34851-8.

- 1 2 Miller, David (2011). Child and Adolescent Suicidal Behavior: School-Based Prevention, Assessment, and Intervention. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-60623-997-1.

- ↑ Hall 1987, p.282

- ↑ Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple. San Diego State University.Archived 24 January 2011 at WebCite

- ↑ "1978:Mass Suicide Leaves 900 Dead". Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ↑ John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945, Random House, 1970, p. 519

- ↑ Suicide and Self-Starvation, Terence M. O'Keeffe, Philosophy, Vol. 59, No. 229 (Jul., 1984), pp. 349–363

- ↑ Watson, Bruce (2007). Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942–43. Stackpole Books. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (August 25, 2008). "In Salmonella Attack, Taking One for the Team". New York Times.

- ↑ Tofilski,Adam; Couvillon, MJ;Evison, SEF; Helantera, H; Robinson, EJH; Ratnieks, FLW (2008). "Preemptive Defensive Self-Sacrifice by Ant Workers" (PDF). The American Naturalist 172 (5): E239–E243. doi:10.1086/591688. PMID 18928332.

- ↑ Larry O'Hanlon (Mar 10, 2010). "Animal Suicide Sheds Light on Human Behavior". Discovery News.

- ↑ "Life In The Undergrowth". BBC.

- ↑ Bordereau, C; Robert, A.; Van Tuyen, V.; Peppuy, A. (August 1997). "Suicidal defensive behaviour by frontal gland dehiscence in Globitermes sulphureus Haviland soldiers (Isoptera)". Insectes Sociaux (Birkhäuser Basel) 44 (3): 289–297. doi:10.1007/s000400050049.

- ↑ Nobel, Justin (Mar 19, 2010). "Do Animals Commit Suicide? A Scientific Debate". Time.

- ↑ Stoff, David; Mann, J. John (1997). "Suicide Research". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences (Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences) 836 (Neurobiology of Suicide, The : From the Bench to the Clinic): 1–11. Bibcode:1997NYASA.836....1S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52352.x.

Further reading

| Library resources about Suicide |

- Gambotto, Antonella (2004). The Eclipse: A Memoir of Suicide. Australia: Broken Ankle Books. ISBN 0-9751075-1-8.

- Goeschel, Christian (2009). Suicide in Nazi Germany. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-953256-7.

External links

- Suicide at DMOZ

- Preventing suicide: a global imperative. (PDF). WHO. 2014. ISBN 9789241564779.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|