Combinatorial chemistry

Combinatorial chemistry comprises chemical synthetic methods that make it possible to prepare a large number (tens to thousands or even millions) of compounds in a single process. These compound libraries can be made as mixtures, sets of individual compounds or chemical structures generated in silico. Combinatorial chemistry can be used for the synthesis of small molecules and for peptides.

Strategies that allow identification of useful components of the libraries are also part of combinatorial chemistry. The methods used in combinatorial chemistry are applied outside chemistry, too.

Introduction

Synthesis of molecules in a combinatorial fashion can quickly lead to large numbers of molecules. For example, a molecule with three points of diversity (R1, R2, and R3) can generate  possible structures, where

possible structures, where  ,

,  , and

, and  are the numbers of different substituents utilized.

are the numbers of different substituents utilized.

The basic principle of combinatorial chemistry is to prepare libraries of very large number of compounds then identify the useful components of the libraries.

Although combinatorial chemistry has only really been taken up by industry since the 1990s, its roots can be seen as far back as the 1960s when a researcher at Rockefeller University, Bruce Merrifield, started investigating the solid-phase synthesis of peptides.

In its modern form, combinatorial chemistry has probably had its biggest impact in the pharmaceutical industry. Researchers attempting to optimize the activity profile of a compound create a 'library' of many different but related compounds. Advances in robotics have led to an industrial approach to combinatorial synthesis, enabling companies to routinely produce over 100,000 new and unique compounds per year.

In order to handle the vast number of structural possibilities, researchers often create a 'virtual library', a computational enumeration of all possible structures of a given pharmacophore with all available reactants.[1] Such a library can consist of thousands to millions of 'virtual' compounds. The researcher will select a subset of the 'virtual library' for actual synthesis, based upon various calculations and criteria (see ADME, computational chemistry, and QSAR).

Combinatorial Synthesis - Peptides

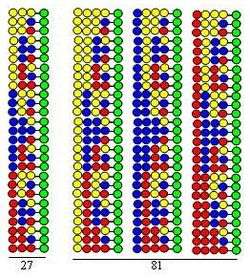

The combinatorial “split-mix synthesis”[2] is based on the solid phase synthesis developed by Merrifield.[3] If a combinatorial peptide library is synthesized using 20 amino acids (or other kinds of building blocks) the bead form solid support is divided into 20 equal portions. This is followed by coupling a different amino acid to each portion. The third step is mixing of all portions. These three steps comprise a cycle. Elongation of the peptide chains can be realized by simply repeating the steps of the cycle.

The procedure is illustrated by the synthesis of a dipeptide library using the same three amino acids as building blocks in both cycles. Each component of this library contains two amino acids arranged in different orders. The amino acids used in couplings are represented by yellow, blue and red circles in the figure. Divergent arrows show dividing solid support resin (green circles) into equal portions, vertical arrows mean coupling and convergent arrows represent mixing and homogenizing the portions of the support.

The figure shows that in the two synthetic cycles 9 dipeptides are formed. In a third and fourth cycles 27 tripeptides and 81 tetrapeptides would form, respectively.

The “split-mix synthesis” has several outstanding features:

- It is highly efficient. As the figure demonstrates the number of peptides formed in the synthetic process (3, 9, 27, 81) increases exponentially with the number of executed cycles. Using 20 amino acids in each synthetic cycle the number of formed peptides are: 400, 8,000, 160,000 and 3,200,000, respectively. This means that the number of peptides increases exponentially with the number of the executed cycles.

- All peptide sequences are formed in the process that can be deduced by combination of the amino acids used in the cycles.

- Portioning of the support into equal samples assures formation of the components of the library in nearly equal molar quantities.

- Only a single peptide forms on each bead of the support. This is the consequence of using only one amino acid in the coupling steps. It is completely unknown, however, which is the peptide that occupies a selected bead.

- The split-mix method can be used for the synthesis of organic or any other kind of library that can be prepared from its building blocks in a stepwise process.

Dr. George Pieczenik worked in the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology at intervals during the years 1972-1987. He was an early worker in the field of combinatorial peptide libraries and is the named inventor of U.S. Patent Nos. 5,866,363 and 6,605,448. The Medical Research Council has its own patents in the field of combinatorial libraries.

Dr. Pieczenik published two papers arising from his time at LMB. The first is entitled “Bacteriophage φ80-induced low molecular weight RNA” co-authored with B.G. Barrell and M.L. Gefter (Arch. Biochim. Biophys. 152: 52-165 (1972)). The second paper, co-authored with F.H.C. Crick, S. Brenner and A. Klug, on “A speculation on the origin of protein synthesis” published in the journal Origins of Life, 7:389-397 (1976), was stimulated by an idea of Pieczenik’s. In 1990 three groups described methods for preparing peptide libraries by biological methods[4][5][6] and one year later Fodor et al. published a remarkable method for synthesis of peptide arrays on small glass slides.[7]

A “parallel synthesis” method was developed by Mario Geysen and his colleagues for preparation of peptide arrays.[8] They synthesized 96 peptides on plastic rods (pins) coated at their ends with the solid support. The pins were immersed into the solution of reagents placed in the wells of a microtiter plate. The method is widely applied particularly by using automatic parallel synthesizers. Although the parallel method is much slower than the real combinatorial one, its advantage is that it is exactly known which peptide or other compound forms on each pin.

Further procedures were developed to combine the advantages of both split-mix and the parallel synthesis. In the method described by two groups[9][10] the solid support was enclosed into permeable plastic capsules together with a radiofrequency tag that carried the code of the compound to be formed in the capsule. The procedure was carried out similar to the split-mix method. In the split step, however, the capsules were distributed among the reaction vessels according to the codes read from the radiofrequency tags of the capsules.

A different method for the same purpose was developed by Furka et al.[11] is named “string synthesis”. In this method the capsules carried no code. They are stringed like the pearls in a necklace and placed into the reaction vessels in stringed form. The identity of the capsules, as well as their contents, are stored by their position occupied on the strings. After each coupling step the capsules are redistributed among new strings according to definite rules.

Combinatorial Synthesis - Small Molecules

Dynamic combinatorial chemistry[12][13][14] uses a different approach for the synthesis of compound libraries. Dynamic combinatorial libraries are generated from an array of reactive building blocks that can react with one another through reversible reactions. In this case, the product distribution in the library is determined by the relative stability of the members. A component of the library can be stabilized by adding a template than can form non-covalent bonds with it. This alters the product distribution and favors the formation of the stabilized library member at the expense of the components.

Deconvolution and screening

The synthesized molecules of a combinatorial library are 'cleaved' from the solid support and mixed into solution. In such solution, millions of different compounds may be found. When this synthetic method was developed, it first seemed impossible to identify the molecules, and to find molecules with useful properties. Strategies of purification, identification, and screening were developed, however, to solve the problem. All these strategies are based on synthesis and testing of partial libraries.

The earliest strategy, the “Iteration method” is described in the above-mentioned document of Furka notarized in 1982. Identification of the sequence of the active peptide involves removal of samples after each coupling step of the synthesis before mixing. These samples are used in the step-by-step identification by testing and coupling starting at the N-terminus.

The “Positional scanning” method[15] is based on synthesis and testing of a series of sub-libraries in which a certain sequence position in all components is occupied by the same amino acid.

“Omission libraries”[16][17] in which a certain amino acid is missing from all peptides of the mixture as well as “amino acid tester libraries”[18] that contain those peptides that are missing from the omission libraries can also be used in the deconvolution process.

If the peptides are not cleaved from the solid support we deal with a mixture of beads, each bead containing a single peptide. Smith and his colleagues[19] showed earlier that peptides could be tested in tethered form, too. This approach was also used in screening peptide libraries.[20] The tethered peptide library was tested with a dissolved target protein. The beads to which the protein was attached were picked out, removed the protein from the bead then the tethered peptide was identified by sequencing.

A somewhat different approach was followed by Taylor and Morken.[21] They used infrared thermography to identify catalysts in non-peptide tethered libraries. When the beads were immersed into a solution of a substrate. the catalyst containing beads were glowing because of the heat evolved in them and could be picked out.

The components of combinatorial libraries can also be tested one by one after cleaving them from the individual beads.

If we deal with a non-peptide organic libraries library it is not as simple to determine of the identity of the content of a bead as in the case of a peptide one. In order to circumvent this difficulty methods were developed to attach to the beads, in parallel with the synthesis of the library, molecules that encode the identity of the compound formed in the bead. The attached molecules may form peptide[22][23] or nucleotide[24][25] sequences or a binary code.[26]

Materials science

Materials science has applied the techniques of combinatorial chemistry to the discovery of new materials. This work was pioneered by P.G. Schultz et al. in the mid nineties[27] in the context of luminescent materials obtained by co-deposition of elements on a silicon substrate. His work was preceded by J. J. Hanak in 1970[28] but the computer and robotics tools were not available for the method to spread at the time. Work has been continued by several academic groups[29][30][31][32] as well as companies with large research and development programs (Symyx Technologies, GE, Dow Chemical etc.). The technique has been used extensively for catalysis,[33] coatings,[34] electronics,[35] and many other fields.[36] The application of appropriate informatics tools is critical to handle, administer, and store the vast volumes of data produced.[37] New types of Design of experiments methods have also been developed to efficiently address the large experimental spaces that can be tackled using combinatorial methods.[38]

Diversity-oriented libraries

Even though combinatorial chemistry has been an essential part of early drug discovery for more than two decades, so far only one de novo combinatorial chemistry-synthesized chemical has been approved for clinical use by FDA (sorafenib, a multikinase inhibitor indicated for advanced renal cancer).[39] The analysis of poor success rate of the approach has been suggested to connect with the rather limited chemical space covered by products of combinatorial chemistry.[40] When comparing the properties of compounds in combinatorial chemistry libraries to those of approved drugs and natural products, Feher and Schmidt[41] noted that combinatorial chemistry libraries suffer particularly from the lack of chirality, as well as structure rigidity, both of which are widely regarded as drug-like properties. Even though natural product drug discovery has not probably been the most fashionable trend in pharmaceutical industry in recent times, a large proportion of new chemical entities still are nature-derived compounds, and thus, it has been suggested that effectiveness of combinatorial chemistry could be improved by enhancing the chemical diversity of screening libraries.[42] As chirality and rigidity are the two most important features distinguishing approved drugs and natural products from compounds in combinatorial chemistry libraries, these are the two issues emphasized in so-called diversity oriented libraries, i.e. compound collections that aim at coverage of the chemical space, instead of just huge numbers of compounds.

Patent classification subclass

In the 8th edition of the International Patent Classification (IPC), which entered into force on January 1, 2006, a special subclass has been created for patent applications and patents related to inventions in the domain of combinatorial chemistry: "C40B".

See also

- Combinatorics

- Cheminformatics

- Combinatorial biology

- Drug discovery

- Dynamic combinatorial chemistry

- High-throughput screening

- Mathematical chemistry

- Molecular modeling

References

- ↑ E. V.Gordeeva et al. "COMPASS program - an original semi-empirical approach to computer-assisted synthesis" Tetrahedron, 48 (1992) 3789.

- ↑ Á. Furka, F. Sebestyen, M. Asgedom, G. Dibo, General method for rapid synthesis of multicomponent peptide mixtures. Int. J. Peptide Protein Res., 1991, 37, 487-493.

- ↑ Merrifield RB, 1963 J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85, 2149.

- ↑ J. K. Scott and G. P. Smith Science 1990, 249, 404.

- ↑ S. Cwirla, E. A. Peters, R. W. Barrett and W. J. Dower Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 6378.

- ↑ J. J. Devlin, L. C. Panganiban and P. E. Devlin Science 1990, 249, 404.

- ↑ Fodor SP, Read JL, Pirrung MC, Stryer L, Lu AT, Solas D, 1991. Light-directed, spatially addressable parallel chemical synthesis. Science 251, 767-73.

- ↑ H. M. Geysen, R. H. Meloen, S. J. Barteling Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1984, 81, 3998.

- ↑ E. J. Moran, S. Sarshar, J. F. Cargill, M. Shahbaz, A Lio, A. M. M. Mjalli, R. W. Armstrong J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 10787.

- ↑ K. C. Nicolaou, X –Y. Xiao, Z. Parandoosh, A. Senyei, M. P. Nova Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1995, 36, 2289.

- ↑ Á. Furka, J. W. Christensen, E. Healy, H. R. Tanner, H. Saneii J. Comb. Chem. 2000, 2, 220.

- ↑ Lehn, J.-M.; Ramström, O. Generation and screening of a dynamic combinatorial library. PCT. Int. Appl. WO 20010164605, 2001.

- ↑ Corbett, P. T.; Leclaire, J.; Vial, L.; West, K. R.; Wietor, J.-L.; Sanders, J. K. M.; Otto, S. (Sep 2006). "Dynamic combinatorial chemistry". Chem. Rev. 106 (9): 3652–3711.

- ↑ Lehn , J. - M. ( 2007 ) Chem. Soc. Rev . ,36 , 151 – 160.

- ↑ Á. Furka, F. Sebestyén WO 93/24517.

- ↑ T. Carell, E. A. Winter, J. Rebek Jr. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1994, 33, 2061.

- ↑ E. Câmpian, M. Peterson, H. H. Saneii, Á. Furka Bioorg. & Med. Chem. Letters 1998, 8, 2357.

- ↑ E. Câmpian, J. Chou, M. L. Peterson, H. H. Saneii, Á. Furka, R. Ramage, R. Epton (Eds) In Peptides 1996, 1998, Mayflower Scientific Ltd. England, 131.

- ↑ J. A. Smith J. G. R. Hurrel, S. J. Leach Immunochemistry 1977, 14, 565.

- ↑ K. S. Lam, S. E. Salmon, E. M. Hersh, V. J. Hruby, W. M. Kazmierski, R. J. Knapp Nature 1991, 354, 82; and its correction: K. S. Lam, S. E. Salmon, E. M. Hersh, V. J. Hruby, W. M. Kazmierski, R. J. Knapp Nature 1992, 360, 768.

- ↑ S. J. Taylor, J. P. Morken Science 1998, 280, 267.

- ↑ J. Nielsen, S. Brenner, K. D. Janda J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 9812.

- ↑ V. Nikolaiev, A. Stierandova, V. Krchnak, B. Seligman, K. S. Lam, S. E. Salmon, M. Lebl Pept. Res. 1993, 6, 161.

- ↑ S. Brenner and R. A. Lerner Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 5381.

- ↑ J. Nielsen, S. Brenner, K. D. Janda J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 9812.

- ↑ M. H. J. Ohlmeyer, R. N. Swanson, L. W. Dillard, J. C. Reader, G. Asouline, R. Kobayashi, M. Wigler, W. C. Still Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1993, 90, 10922.

- ↑ X. -D. Xiang et al. "A Combinatorial Approach to Materials Discovery" Science 268 (1995) 1738

- ↑ J.J. Hanak, J. Mater. Sci, 1970, 5, 964-971

- ↑ Combinatorial methods for development of sensing materials, Springer, 2009. ISBN 978-0-387-73712-6

- ↑ V. M. Mirsky, V. Kulikov, Q. Hao, O. S. Wolfbeis. Multiparameter High Throughput Characterization of Combinatorial Chemical Microarrays of Chemosensitive Polymers. Macromolec. Rap. Comm., 2004, 25, 253-258

- ↑ H. Koinuma et al. "Combinatorial solid state materials science and technology" Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 1 (2000) 1 free download

- ↑ Andrei Ionut Mardare et al. "Combinatorial solid state materials science and technology" Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 9 (2008) 035009 free download

- ↑ Applied Catalysis A, Volume 254, Issue 1, Pages 1-170 (10 November 2003)

- ↑ , J. N. Cawse et. al, Progress in Organic Coatings, Volume 47, Issue 2, August 2003, Pages 128-135

- ↑ Combinatorial Methods for High-Throughput Materials Science, MRS Proceedings Volume 1024E, Fall 2007

- ↑ Combinatorial and Artificial Intelligence Methods in Materials Science II, MRS Proceedings Volume 804, Fall 2004

- ↑ QSAR and Combinatorial Science, 24, Number 1 (February 2005)

- ↑ J. N. Cawse, Ed., Experimental Design for Combinatorial and High Throughput Materials Development, John Wiley and Sons, 2002.

- ↑ D. Newman and G. Cragg "Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Last 25 Years" J Nat Prod 70 (2007) 461

- ↑ M. Feher and J. M. Schmidt "Property Distributions: Differences between Drugs, Natural Products, and Molecules from Combinatorial Chemistry" J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci., 43 (2003) 218

- ↑ M. Feher and J. M. Schmidt "Property Distributions: Differences between Drugs, Natural Products, and Molecules from Combinatorial Chemistry" J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci., 43 (2003) 218

- ↑ Su QB, Beeler AB, Lobkovsky E, Porco JA, Panek JS "Stereochemical diversity through cyclodimerization: Synthesis of polyketide-like macrodiolides." Org Lett 2003, 5:2149-2152.

External links

- English version of the 1982 document

- “The concealed side of the history of combinatorial chemistry”

- IUPAC's "Glossary of Terms Used in Combinatorial Chemistry"

- ACS Combinatorial Science (formerly Journal of Combinatorial Chemistry)

- Combinatorial Chemistry Review

- Molecular Diversity

- Combinatorial Chemistry and High Throughput Screening

- Combinatorial Chemistry: an Online Journal

- SmiLib - A free open-source software for combinatorial library enumeration

- GLARE - A free open-source software for combinatorial library design