Colville Indian Reservation

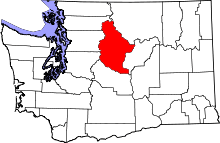

The Colville Indian Reservation is a Native American reservation in the north-central part of the U.S. state of Washington, inhabited and managed by the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, which is federally recognized. The reservation is located primarily in the southeastern section of Okanogan County and the southern half of Ferry County, but it includes other pieces of trust land in eastern Washington, including in Chelan County, just to the northwest of the city of Chelan. The reservation's name is adapted from that of Fort Colville, which was named for Andrew Colville, who was a London governor of the Hudson's Bay Company.

The Confederated Tribes have 8,700 descendants from 12 aboriginal tribes. The tribes are known in English as: the Colville, the Nespelem, the Sanpoil, the Lakes (after the Arrow Lakes of British Columbia or Sinixt), the Palus, the Wenatchee, the Chelan, the Entiat, the Methow, the southern Okanagan, the Sinkiuse-Columbia, and the Nez Perce of Chief Joseph's Band. Some members of the Spokane tribe also settled the Colville reservation later on.

The most common of the indigenous languages spoken on the reservation is Colville-Okanagan, a Salishan language. Other tribes speak other Salishan languages, with the exception of the Nez Perce and Palus, who speak Sahaptian languages.

History

Before the influx of British and Americans in the mid-1850s, the ancestors of the 12 aboriginal tribes followed seasonal cycles of food availability; moving to the rivers for fish runs, mountain meadows for berries and deer, or the plateau for roots. Their traditional territories were grouped primarily around waterways, such as the Columbia, San Poil, Nespelem, Okanogan, Snake, and Wallowa rivers.

Many tribal ancestors ranged throughout their aboriginal territories and other areas in the Northwest (including British Columbia, Canada), gathering with other native peoples for traditional activities such as food harvesting, feasting, trading, and celebrations that included sports and gambling. Their lives were tied to the cycles of nature, both spiritually and traditionally.[1]

In the mid-19th century, when settlers began competing for trade with the indigenous native peoples, many tribes began to migrate westward. Trading became a bigger part of their lives.

For a while, there was an ownership dispute between Great Britain and the United States over what the latter called the Oregon Country and the former the Columbia District. Both claimed the territory until the Oregon Treaty of 1846 established United States title south of the 49th Parallel. They did not consider any of the indigenous peoples living in those territories to be citizens or entitled to the lands by their own national claim. However, according to the religions and traditions of the indigenous peoples, this territory had been their home land since the time of creation.

President Fillmore signed a bill creating the Washington Territory, and he appointed a Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Major Isaac Stevens of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, to meet with the Indians during his exploration for railroad routes. Stevens wrote a report recommending the creation of "reservations" for the people in the Washington Territory. The report said, "contrary to natural rights and usage," the United States should grant lands that would become reservations to the Indians without purchasing from them.

In 1854 negotiations were conducted, "particularly in the vicinity of white settlements, toward extinguishment of the Indian claims to the lands and the concentration of the tribes and fragments of tribes on a few reservations naturally suited to the requirement of the Indians, and located, so far as practicable, so as not to interfere with the settlement of the country."

During this time, continued American settlement created conflicts and competition for resources; it resulted in the Yakima War, which was fought from 1856 to 1859. Negotiations were unsuccessful until 1865. Superintendent McKenny then commented:

From this report, the necessity of trading with these Indians can scarcely fail to be obvious. They now occupy the best agricultural lands in the whole country and they claim an undisputed right to these lands. White squatters are constantly making claims in their territory and not infrequently invading the actual improvements of the Indians. The state of things cannot but prove disastrous to the peace of the country unless forestalled by a treaty fixing the rights of the Indians and limiting the aggressions of the white man. The fact that a portion of the Indians refused all gratuitous presents shows a determination to hold possession of the country here until the government makes satisfactory overtures to open the way of actual purchase.

President Grant issued an Executive Order on April 9, 1872, to create an "Indian Reservation" consisting of several million acres of land, containing rivers, streams, timbered forests, grass lands, minerals, plants and animals. People from 11 tribes (the Colville, the Nespelem, the San Poil, Lakes (Sinixt), Palus, Wenatchi, Chelan, Entiat, Methow, southern Okanogan, and the Moses Columbia) were "designated" to live on a new Colville Indian Reservation.

That original reservation was west of the Columbia River, but less than three months later, the President issued another executive order on July 2, 1872 moving it west, to reach from the Columbia River on the west and south to the Okanogan River on the east and the Canadian border to the north. The new reservation was smaller, at 2,852,000 acres (11,540 km²). The Tribes' native lands of the Okanogan River, Methow Valley, and other large areas along the Columbia and Pend d'Orielle rivers, along with the Colville Valley, were excluded. The areas removed from the reservation were some of the richest in terms of natural resources.

Twenty years later, the dissolution of Indian reservations throughout the United States begun by the General Allotment Act (Dawes Act) of 1887 came to the Colville reservation. An 1892 act of Congress removed the north half of the reservation (now known as the Old North Half) from tribal control, with allotments made to Indians then living on it and the rest opened up for settlement. In 1891, the tribes had entered into an agreement with the federal government to vacate the Old North Half, in exchange for $1.5 million ($1 per acre) and continued hunting and fishing rights, but the 1892 act was based only loosely on that agreement. The payment was, however, ultimately made 14 years later and the hunting and fishing rights for tribe members (superior to those of non-members) endure to this day. As was normal in reservation allotments, individual Indians living on the Old North Half who chose not to move to the remaining south half were given 80 acres of land.

The Old North Half is everything north of Township 34.

The remainder of the reservation was allotted out, in the same 80 acre amounts, and tribal authority ended, by act of Congress in 1906, with the land not allotted to individual Indians opened for settlement by Presidential proclamation in 1916. The allotment act was based on an agreement negotiated between the tribes and Indian agent James McLaughlin, signed by 2/3 of the adult male Indians then living on the reservation (of whom there were approximately 600). It is important to remember that the Dawes Act enacted a policy of terminating reservations and did not require any consent by or compensation to Indians, so agreements that Indians did sign were not entirely mutual. They concerned more the details of the allotment than the fact of it.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 reversed the policy of dissolution of reservations and immediately halted the ongoing transfer of reservation land to private ownership. In 1956, Congress restored tribal control over all land in the south half that was not yet privately owned. In the time since then, the tribe has gradually purchased private land on the reservation and had it placed back into trust status as tribal land. Some of the funds for this has come from the federal government, pursuant to lawsuits, as compensation for the government's mismanagement of the trust lands and insufficient compensation to Indians for former reservation land.

Current

The reservation encompasses 2,116.802 acres (8,566.39 km²) of land, consisting of: tribally owned lands held in federal trust status for the Colville Confederated Tribes, land owned by individual Colville tribal members (most of which is also held in federal trust status), and land owned by other tribal or non-tribal entities.

7,587 people live on the reservation (2000 census), both Colville tribe members and non-tribe members, living either in small communities or in rural settings. Approximately half of the Confederated Tribes' members live on or near the reservation.

Major towns and cities include Omak (part), Nespelem, Inchelium, Keller, and Coulee Dam (part).

Legislative districts

The legislative districts (each with representation on the Colville Business Council) are as follows.

- Omak District: The largest district by population, this consists of the northwestern portion of the reservation: the Okanogan Valley and the eastern portion of the city of Omak. The Okanogan River is the western border of the reservation and delimits the reservation portion of Omak.

- Nespelem District: This is the west-central portion of the reservation, including the Nespelem Valley and part of the city of Coulee Dam. The Reservation Headquarters is located in the district on the Bureau of Indian Affairs Agency campus near the town of Nespelem. In Coulee Dam, the Columbia River also serves as a reservation border within the town limits.

- Keller District: Thi is the east-central region of the reservation, namely the San Poil Valley to the mouth of the Columbia River, along a tributary, the San Poil River, and the edge of the man-made Lake Roosevelt.

- Inchelium District: This is the north-east part of the reservation.

In 1997 and 1998, the Colville Confederated Tribes commemorated the 125th anniversary of the signing of the Executive Order that created the reservation.

Communities

- Coulee Dam (part, population 915)

- Disautel

- Elmer City

- Inchelium

- Keller

- Nespelem

- Nespelem Community (Agency area)

- North Omak

- Okanogan (a small part, population 2)

- Omak (part, population 742)

- Twin Lakes

Government

The Confederated Tribes and the Colville Indian Reservation are governed by the Colville Business Council[2] From its administrative headquarters located at the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) Agency at Nespelem, burned down on July 29, 2013 from a large fire,[3] the Colville Business Council oversees a diverse, multimillion-dollar administration that employs from 800 to 1,200 individuals in permanent, part-time, and seasonal positions. Members of the Colville Business Council are elected to a renewable two-year term of office. There are four council members for each district, except for the Keller District, which has two. Each year, half of the Business Council seats in each district are up for election. Elections are held mid-June, with votes cast in person at polling sites at a predesignated location (usually the local community center) or by absentee ballot.

Education

The current education system set for the Colville Indian Reservation is that each town on the reservation has its own K-6 school either directly or partially affiliated with the tribes. The Omak and Okanogan school districts serve the students of that area from Kindergarten-12. The Nespelem school district has a Kindergarten-8 system; most Nespelem students attend high school at nearby Lake Roosevelt High School in the town of Coulee Dam.

The Keller school district serves students from Kindergarten-6. It gives students the option of attending junior and senior high school at relatively nearby Wilbur High School, Lake Roosevelt High School or Republic High School. Due to historically negative perceptions about Native Americans, students from Keller seldom attend the school in the predominantly European-American town of Republic. Students sometimes encounter discrimination and poor perceptions also in Wilbur, Coulee Dam, and other towns neighboring the reservation.

Pascal Sherman Indian School, located outside Omak at St. Mary's Mission, is the only Native American residential school on the reservation currently serving grades pre-K-to-9. The tribe wants to develop a high school there as well. Inchelium School district and Lake Roosevelt High School are the only public K-12 schools within the physical boundaries of the reservation.

Students have few options to pursue a post-secondary education on the reservation. The Community Colleges of Spokane have an outreach campus in Inchelium. Big Bend Community College has a similar campus in Grand Coulee. Spokane Tribal College has a joint venture on Nespelem's Agency Campus. Wenatchee Valley College North Campus is located in Omak.

Many students from the reservation typically attend four-year college in the state, at such institutions as Eastern Washington University, Washington State University, Central Washington University, Gonzaga University (founded to serve Native Americans) or University of Washington. Heritage College also offers some courses and degrees in Omak at the Wenatchee Valley College-North Campus building.

Legends and stories

- Coyote and the buffalo- Colville legend about why buffalo don't live near Kettle Falls.

- Coyote quarrels with mole- Colville legend about coyote fighting with his wife.

- Spirit chief names the animal people- Colville legend about the naming of the Chip-chap-tiqulk.

- Turtle and the eagle- Colville folktale about turtle winning a race.

References

- ↑

- ↑ Colville Business Council Confederation Tribes of the Colville Reservation. Accessed 2009-10-05.

- ↑ "Fire destroys Colville tribal HQ in Nespelem". The Spokesman-Review. July 29, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- Colville Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Washington United States Census Bureau

External links

- Official site of the Colville Confederated Tribes

- Colville Business (Tribal) Council

- Facts about The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation

- The Colville.

- Colville Tribal Enterprises Corporation

- Okanagan Nation Alliance (includes the Colville Confederated Tribes as well as Okanagans in Canada).

- Ceremony marks return of salmon, tradition to Colville Reservation- Natural Resources Conservation Service, Washington

Coordinates: 48°13′47″N 118°52′22″W / 48.22972°N 118.87278°W

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||