Collaborative filtering

| Recommender systems |

|---|

| Concepts |

| Methods and challenges |

| Implementations |

| Research |

Collaborative filtering (CF) is a technique used by some recommender systems.[1] Collaborative filtering has two senses, a narrow one and a more general one.[2] In general, collaborative filtering is the process of filtering for information or patterns using techniques involving collaboration among multiple agents, viewpoints, data sources, etc.[2] Applications of collaborative filtering typically involve very large data sets. Collaborative filtering methods have been applied to many different kinds of data including: sensing and monitoring data, such as in mineral exploration, environmental sensing over large areas or multiple sensors; financial data, such as financial service institutions that integrate many financial sources; or in electronic commerce and web applications where the focus is on user data, etc. The remainder of this discussion focuses on collaborative filtering for user data, although some of the methods and approaches may apply to the other major applications as well.

In the newer, narrower sense, collaborative filtering is a method of making automatic predictions (filtering) about the interests of a user by collecting preferences or taste information from many users (collaborating). The underlying assumption of the collaborative filtering approach is that if a person A has the same opinion as a person B on an issue, A is more likely to have B's opinion on a different issue x than to have the opinion on x of a person chosen randomly. For example, a collaborative filtering recommendation system for television tastes could make predictions about which television show a user should like given a partial list of that user's tastes (likes or dislikes).[3] Note that these predictions are specific to the user, but use information gleaned from many users. This differs from the simpler approach of giving an average (non-specific) score for each item of interest, for example based on its number of votes.

Introduction

The growth of the Internet has made it much more difficult to effectively extract useful information from all the available online information. The overwhelming amount of data necessitates mechanisms for efficient information filtering. One of the techniques used for dealing with this problem is called collaborative filtering.

The motivation for collaborative filtering comes from the idea that people often get the best recommendations from someone with similar tastes to themselves. Collaborative filtering explores techniques for matching people with similar interests and making recommendations on this basis.

Collaborative filtering algorithms often require (1) users’ active participation, (2) an easy way to represent users’ interests to the system, and (3) algorithms that are able to match people with similar interests.

Typically, the workflow of a collaborative filtering system is:

- A user expresses his or her preferences by rating items (e.g. books, movies or CDs) of the system. These ratings can be viewed as an approximate representation of the user's interest in the corresponding domain.

- The system matches this user’s ratings against other users’ and finds the people with most “similar” tastes.

- With similar users, the system recommends items that the similar users have rated highly but not yet being rated by this user (presumably the absence of rating is often considered as the unfamiliarity of an item)

A key problem of collaborative filtering is how to combine and weight the preferences of user neighbors. Sometimes, users can immediately rate the recommended items. As a result, the system gains an increasingly accurate representation of user preferences over time.

Methodology

Collaborative filtering systems have many forms, but many common systems can be reduced to two steps:

- Look for users who share the same rating patterns with the active user (the user whom the prediction is for).

- Use the ratings from those like-minded users found in step 1 to calculate a prediction for the active user

This falls under the category of user-based collaborative filtering. A specific application of this is the user-based Nearest Neighbor algorithm.

Alternatively, item-based collaborative filtering (users who bought x also bought y), proceeds in an item-centric manner:

- Build an item-item matrix determining relationships between pairs of items

- Infer the tastes of the current user by examining the matrix and matching that user's data

See, for example, the Slope One item-based collaborative filtering family.

Another form of collaborative filtering can be based on implicit observations of normal user behavior (as opposed to the artificial behavior imposed by a rating task). These systems observe what a user has done together with what all users have done (what music they have listened to, what items they have bought) and use that data to predict the user's behavior in the future, or to predict how a user might like to behave given the chance. These predictions then have to be filtered through business logic to determine how they might affect the actions of a business system. For example, it is not useful to offer to sell somebody a particular album of music if they already have demonstrated that they own that music.

Relying on a scoring or rating system which is averaged across all users ignores specific demands of a user, and is particularly poor in tasks where there is large variation in interest (as in the recommendation of music). However, there are other methods to combat information explosion, such as web search and data clustering.

Types

Memory-based

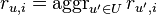

This approach uses user rating data to compute the similarity between users or items. This is used for making recommendations. This was an early approach used in many commercial systems. It's effective and easy to implement. Typical examples of this approach are neighbourhood-based CF and item-based/user-based top-N recommendations. For example, in user based approaches, the value of ratings user 'u' gives to item 'i' is calculated as an aggregation of some similar users' rating of the item:

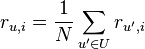

where 'U' denotes the set of top 'N' users that are most similar to user 'u' who rated item 'i'. Some examples of the aggregation function includes:

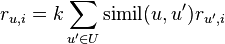

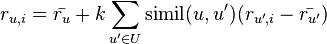

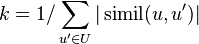

where k is a normalizing factor defined as  . and

. and  is the average rating of user u for all the items rated by u.

is the average rating of user u for all the items rated by u.

The neighborhood-based algorithm calculates the similarity between two users or items, produces a prediction for the user by taking the weighted average of all the ratings. Similarity computation between items or users is an important part of this approach. Multiple measures, such as Pearson correlation and vector cosine based similarity are used for this.

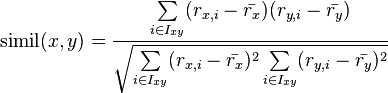

The Pearson correlation similarity of two users x, y is defined as

where Ixy is the set of items rated by both user x and user y.

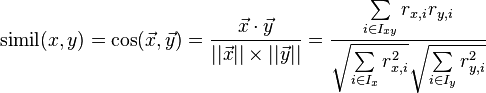

The cosine-based approach defines the cosine-similarity between two users x and y as:[4]

The user based top-N recommendation algorithm uses a similarity-based vector model to identify the k most similar users to an active user. After the k most similar users are found, their corresponding user-item matrices are aggregated to identify the set of items to be recommended. A popular method to find the similar users is the Locality-sensitive hashing, which implements the nearest neighbor mechanism in linear time.

The advantages with this approach include: the explainability of the results, which is an important aspect of recommendation systems; easy creation and use; easy facilitation of new data; content-independence of the items being recommended; good scaling with co-rated items.

There are also several disadvantages with this approach. Its performance decreases when data gets sparse, which occurs frequently with web-related items. This hinders the scalability of this approach and creates problems with large datasets. Although it can efficiently handle new users because it relies on a data structure, adding new items becomes more complicated since that representation usually relies on a specific vector space. Adding new items requires inclusion of the new item and the re-insertion of all the elements in the structure.

Model-based

Models are developed using data mining, machine learning algorithms to find patterns based on training data. These are used to make predictions for real data. There are many model-based CF algorithms. These include Bayesian networks, clustering models, latent semantic models such as singular value decomposition, probabilistic latent semantic analysis, multiple multiplicative factor, latent Dirichlet allocation and Markov decision process based models.[5]

This approach has a more holistic goal to uncover latent factors that explain observed ratings.[6] Most of the models are based on creating a classification or clustering technique to identify the user based on the training set. The number of the parameters can be reduced based on types of principal component analysis.

There are several advantages with this paradigm. It handles the sparsity better than memory based ones. This helps with scalability with large data sets. It improves the prediction performance. It gives an intuitive rationale for the recommendations.

The disadvantages with this approach are in the expensive model building. One needs to have a tradeoff between prediction performance and scalability. One can lose useful information due to reduction models. A number of models have difficulty explaining the predictions.

Hybrid

A number of applications combines the memory-based and the model-based CF algorithms. These overcome the limitations of native CF approaches. It improves the prediction performance. Importantly, it overcomes the CF problems such as sparsity and loss of information. However, they have increased complexity and are expensive to implement.[7] Usually most of the commercial recommender systems are hybrid, for example, Google news recommender system.[8]

Application on social web

Unlike the traditional model of mainstream media, in which there are few editors who set guidelines, collaboratively filtered social media can have a very large number of editors, and content improves as the number of participants increases. Services like Reddit, YouTube, and Last.fm are typical example of collaborative filtering based media.[9]

One scenario of collaborative filtering application is to recommend interesting or popular information as judged by the community. As a typical example, stories appear in the front page of Digg as they are "voted up" (rated positively) by the community. As the community becomes larger and more diverse, the promoted stories can better reflect the average interest of the community members.

Another aspect of collaborative filtering systems is the ability to generate more personalized recommendations by analyzing information from the past activity of a specific user, or the history of other users deemed to be of similar taste to a given user. These resources are used as user profiling and helps the site recommend content on a user-by-user basis. The more a given user makes use of the system, the better the recommendations become, as the system gains data to improve its model of that user.

Problems

A collaborative filtering system does not necessarily succeed in automatically matching content to one's preferences. Unless the platform achieves unusually good diversity and independence of opinions, one point of view will always dominate another in a particular community. As in the personalized recommendation scenario, the introduction of new users or new items can cause the cold start problem, as there will be insufficient data on these new entries for the collaborative filtering to work accurately. In order to make appropriate recommendations for a new user, the system must first learn the user's preferences by analysing past voting or rating activities. The collaborative filtering system requires a substantial number of users to rate a new item before that item can be recommended.

Challenges of collaborative filtering

Data sparsity

In practice, many commercial recommender systems are based on large datasets. As a result, the user-item matrix used for collaborative filtering could be extremely large and sparse, which brings about the challenges in the performances of the recommendation.

One typical problem caused by the data sparsity is the cold start problem. As collaborative filtering methods recommend items based on users’ past preferences, new users will need to rate sufficient number of items to enable the system to capture their preferences accurately and thus provides reliable recommendations.

Similarly, new items also have the same problem. When new items are added to system, they need to be rated by substantial number of users before they could be recommended to users who have similar tastes with the ones rated them. The new item problem does not limit the content-based recommendation, because the recommendation of an item is based on its discrete set of descriptive qualities rather than its ratings.

Scalability

As the numbers of users and items grow, traditional CF algorithms will suffer serious scalability problems. For example, with tens of millions of customers  and millions of items

and millions of items  , a CF algorithm with the complexity of

, a CF algorithm with the complexity of  is already too large. As well, many systems need to react immediately to online requirements and make recommendations for all users regardless of their purchases and ratings history, which demands a higher scalability of a CF system. Large web companies such as Twitter use clusters of machines to scale recommendations for their millions of users, with most computations happening in very large memory machines.[10]

is already too large. As well, many systems need to react immediately to online requirements and make recommendations for all users regardless of their purchases and ratings history, which demands a higher scalability of a CF system. Large web companies such as Twitter use clusters of machines to scale recommendations for their millions of users, with most computations happening in very large memory machines.[10]

Synonyms

Synonyms refers to the tendency of a number of the same or very similar items to have different names or entries. Most recommender systems are unable to discover this latent association and thus treat these products differently.

For example, the seemingly different items “children movie” and “children film” are actually referring to the same item. Indeed, the degree of variability in descriptive term usage is greater than commonly suspected. The prevalence of synonyms decreases the recommendation performance of CF systems. Topic Modeling (like the Latent Dirichlet Allocation technique) could solve this by grouping different words belonging to the same topic.

Gray sheep

Gray sheep refers to the users whose opinions do not consistently agree or disagree with any group of people and thus do not benefit from collaborative filtering. Black sheep are the opposite group whose idiosyncratic tastes make recommendations nearly impossible. Although this is a failure of the recommender system, non-electronic recommenders also have great problems in these cases, so black sheep is an acceptable failure.

Shilling attacks

In a recommendation system where everyone can give the ratings, people may give lots of positive ratings for their own items and negative ratings for their competitors. It is often necessary for the collaborative filtering systems to introduce precautions to discourage such kind of manipulations.

Diversity and the Long Tail

Collaborative filters are expected to increase diversity because they help us discover new products. Some algorithms, however, may unintentionally do the opposite. Because collaborative filters recommend products based on past sales or ratings, they cannot usually recommend products with limited historical data. This can create a rich-get-richer effect for popular products, akin to positive feedback. This bias toward popularity can prevent what are otherwise better consumer-product matches. A Wharton study details this phenomenon along with several ideas that may promote diversity and the "long tail."[11] Several collaborative filtering algorithms have been developed to promote diversity and the "long tail" by recommending novel, unexpected,[12] and serendipitous items.[13]

Innovations

- New algorithms have been developed for CF as a result of the Netflix prize.

- Cross-System Collaborative Filtering where user profiles across multiple recommender systems are combined in a privacy preserving manner.

- Robust Collaborative Filtering, where recommendation is stable towards efforts of manipulation. This research area is still active and not completely solved.[14]

See also

- Attention Profiling Mark-up Language (APML)

- Cold start

- Collaborative model

- Collaborative search engine

- Collective intelligence

- Customer engagement

- Delegative Democracy, the same principle applied to voting rather than filtering

- Enterprise bookmarking

- Firefly (website), a defunct website which was based on collaborative filtering

- Long tail

- Preference elicitation

- Recommendation system

- Relevance (information retrieval)

- Reputation system

- Robust collaborative filtering

- Similarity search

- Slope One

- Social translucence

References

- ↑ Francesco Ricci and Lior Rokach and Bracha Shapira, Introduction to Recommender Systems Handbook, Recommender Systems Handbook, Springer, 2011, pp. 1-35

- 1 2 Terveen, Loren; Hill, Will (2001). "Beyond Recommender Systems: Helping People Help Each Other" (PDF). Addison-Wesley. p. 6. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ An integrated approach to TV & VOD Recommendations

- ↑ John S. Breese, David Heckerman, and Carl Kadie, Empirical Analysis of Predictive Algorithms for Collaborative Filtering, 1998

- ↑ Xiaoyuan Su, Taghi M. Khoshgoftaar, A survey of collaborative filtering techniques, Advances in Artificial Intelligence archive, 2009.

- ↑ Factor in the Neighbors: Scalable and Accurate Collaborative Filtering

- ↑ "Kernel-Mapping Recommender system algorithms". Information Sciences 208: 81–104. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2012.04.012.

- ↑ Google News Personalization: Scalable Online Collaborative Filtering

- ↑ Collaborative Filtering: Lifeblood of The Social Web

- ↑ Pankaj Gupta, Ashish Goel, Jimmy Lin, Aneesh Sharma, Dong Wang, and Reza Bosagh Zadeh WTF: The who-to-follow system at Twitter, Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on World Wide Web

- ↑ Fleder, Daniel; Hosanagar, Kartik (May 2009). "Blockbuster Culture's Next Rise or Fall: The Impact of Recommender Systems on Sales Diversity". Management Science. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1080.0974.

- ↑ Adamopoulos, Panagiotis; Tuzhilin, Alexander (January 2015). "On Unexpectedness in Recommender Systems: Or How to Better Expect the Unexpected". ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. doi:10.1145/2559952.

- ↑ Adamopoulos, Panagiotis (October 2013). "Beyond rating prediction accuracy: on new perspectives in recommender systems". Proceedings of the 7th ACM conference on Recommender systems. doi:10.1145/2507157.2508073.

- ↑ "Robust collaborative filtering". Portal.acm.org. 19 October 2007. doi:10.1145/1297231.1297240. Retrieved 2012-05-15.

External links

- Beyond Recommender Systems: Helping People Help Each Other, page 12, 2001

- Recommender Systems. Prem Melville and Vikas Sindhwani. In Encyclopedia of Machine Learning, Claude Sammut and Geoffrey Webb (Eds), Springer, 2010.

- Recommender Systems in industrial contexts - PHD thesis (2012) including a comprehensive overview of many collaborative recommender systems

- Toward the next generation of recommender systems: a survey of the state-of-the-art and possible extensions. Adomavicius, G. and Tuzhilin, A. IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 06.2005

- Evaluating collaborative filtering recommender systems (DOI: 10.1145/963770.963772)

- GroupLens research papers.

- Content-Boosted Collaborative Filtering for Improved Recommendations. Prem Melville, Raymond J. Mooney, and Ramadass Nagarajan. Proceedings of the Eighteenth National Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI-2002), pp. 187–192, Edmonton, Canada, July 2002.

- A collection of past and present "information filtering" projects (including collaborative filtering) at MIT Media Lab

- Eigentaste: A Constant Time Collaborative Filtering Algorithm. Ken Goldberg, Theresa Roeder, Dhruv Gupta, and Chris Perkins. Information Retrieval, 4(2), 133-151. July 2001.

- A Survey of Collaborative Filtering Techniques Su, Xiaoyuan and Khoshgortaar, Taghi. M

- Google News Personalization: Scalable Online Collaborative Filtering Abhinandan Das, Mayur Datar, Ashutosh Garg, and Shyam Rajaram. International World Wide Web Conference, Proceedings of the 16th international conference on World Wide Web

- Factor in the Neighbors: Scalable and Accurate Collaborative Filtering Yehuda Koren, Transactions on Knowledge Discovery from Data (TKDD) (2009)

- Rating Prediction Using Collaborative Filtering

- Recommender Systems

- Berkeley Collaborative Filtering

|