Cold agglutinin disease

| Cold agglutinin disease | |

|---|---|

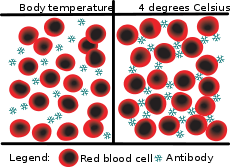

Cold agglutination - at body temperature, the antibodies do not attach to the red blood cells. At lower temperatures, however, the antibodies react to Ii antigens, bringing the red blood cells together, a process known as agglutination | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | hematology |

| ICD-10 | D59.1 |

| ICD-9-CM | 283.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 2949 |

| eMedicine | med/408 |

| MeSH | D000744 |

Cold agglutinin disease is an autoimmune disease characterized by the presence of high concentrations of circulating antibodies, usually IgM, directed against red blood cells.[1] It is a form of autoimmune hemolytic anemia, specifically one in which antibodies only bind red blood cells at low body temperatures, typically 28-31 °C.

It was first described in 1957.[2][3]

Etiology

There are two forms of cold agglutinin disease: 1-primary and 2-secondary.

- The primary form is by definition idiopathic, a disease for which no cause is known.[4]

- Secondary cold agglutinin disease is a result of an underlying condition.

- In adults, this is typically due to a lymphoproliferative disease such as lymphoma and chronic lymphoid leukemia, or infection. Waldenström's macroglobulinemia may also be positive for cold agglutinins.

- In children, cold agglutinin disease is often secondary to an infection, such as Mycoplasma pneumonia, mononucleosis, and HIV.

Pathophysiology

All individuals have circulating antibodies directed against red blood cells, but their concentrations are often too low to trigger disease (titers under 64 at 4 °C). In individuals with cold agglutinin disease, these antibodies are in much higher concentrations (titers over 1000 at 4 °C).

At body temperatures of 28-31 °C, such as those encountered during winter months, and occasionally at body temperatures of 37 °C, antibodies (generally IgM) bind to the polysaccharide region of glycoproteins on the surface of red blood cells (typically the I antigen, i antigen, and Pr antigens). Binding of antibodies to red blood cells activates the classical pathway of the complement system. If the complement response is sufficient, red blood cells are damaged by the membrane attack complex, an effector of the complement cascade. In the formation of the membrane attack complex, several complement proteins are inserted into the red blood cell membrane, forming pores that lead to membrane instability and intravascular hemolysis (destruction of the red blood cell within the blood vessels).

If the complement response is insufficient to form membrane attack complexes, then extravascular lysis will be favored over intravascular red blood cell lysis. In lieu of the membrane attack complex, complement proteins (particularly C3b and C4b) are deposited on red blood cells. This opsonization enhances the clearance of red blood cell by phagocytes in the liver, spleen, and lungs, a process termed extravascular hemolysis.

Individuals with cold agglutinin disease present with signs and symptoms of hemolytic anemia. Those with secondary agglutinin disease may also present with an underlying disease, often autoimmune.

Treatment

- Avoid cold weather.

- Treat the underlying lymphoma.

- No cold drinks; all drinks should be at normal temperature.

- Requires Heater to maintain temperature in cold places.

Treatment with rituximab has been described.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ "Cold Agglutinin Disease: Overview - eMedicine Pediatrics: General Medicine". Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- ↑ Gertz MA (April 2006). "Cold agglutinin disease". Haematologica 91 (4): 439–41. PMID 16585009.

- ↑ DACIE JV, CROOKSTON JH, CHRISTENSON WN (January 1957). "Incomplete cold antibodies role of complement in sensitization to antiglobulin serum by potentially haemolytic antibodies". Br. J. Haematol. 3 (1): 77–87. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.1957.tb05773.x. PMID 13413095.

- ↑ Berentsen S, Beiske K, Tjønnfjord GE (October 2007). "Primary chronic cold agglutinin disease: an update on pathogenesis, clinical features and therapy". Hematology 12 (5): 361–70. doi:10.1080/10245330701445392. PMC 2409172. PMID 17891600.

- ↑ Berentsen S, Ulvestad E, Gjertsen BT; et al. (April 2004). "Rituximab for primary chronic cold agglutinin disease: a prospective study of 37 courses of therapy in 27 patients". Blood 103 (8): 2925–8. doi:10.1182/blood-2003-10-3597. PMID 15070665.