Coffee preparation

Coffee preparation is the process of turning coffee beans into a beverage. While the particular steps vary with the type of coffee and with the raw materials, the process includes four basic steps; raw coffee beans must be roasted, the roasted coffee beans must then be ground, the ground coffee must then be mixed with hot water for a certain time (brewed), and finally the liquid coffee must be separated from the used grounds.

Coffee is usually brewed immediately before drinking. In most areas, coffee may be purchased unprocessed, or already roasted, or already roasted and ground. Coffee is often vacuum packed to prevent oxidation and lengthen its shelf life.

Roasting

Roasting coffee transforms the chemical and physical properties of green coffee beans. When roasted, the green coffee bean expands to nearly double its original size, changing in color and density. As the bean absorbs heat, its color shifts to yellow, then to a light "cinnamon" brown, and then to a rich dark brown color. During roasting, oils appear on the surface of the bean. The roast will continue to darken until it is removed from the heat source.

Coffee can be roasted with ordinary kitchen equipment (frying pan, grill, oven, popcorn popper) or by specialised appliances. A coffee roaster is a special pan or apparatus suitable to heat up and roast green coffee beans.

Grinding

The whole coffee beans are ground, also known as milling, to facilitate the brewing process.

The fineness of the grind strongly affects brewing. Brewing methods that expose coffee grounds to heated water for longer require a coarser grind than faster brewing methods. Beans that are too finely ground for the brewing method in which they are used will expose too much surface area to the heated water and produce a bitter, harsh, "over-extracted" taste. At the other extreme, an overly coarse grind will produce weak coffee unless more is used. Due to the importance of a grind's fineness, a uniform grind is highly desirable.

If a brewing method is used in which the time of exposure of the ground coffee to the heated water is adjustable, then a short brewing time can be used for finely ground coffee. This produces coffee of equal flavor yet uses less ground coffee. A blade grinder does not cause frictional heat buildup in the ground coffee unless used to grind very large amounts as in a commercial operation. A fine grind allows the most efficient extraction but coffee ground too finely will slow down filtration or screening.

Ground coffee deteriorates faster than roasted beans because of the greater surface area exposed to oxygen. Many coffee drinkers grind the beans themselves immediately before brewing.

Spent coffee grinds can be reused for hair care or skin care as well as in the garden. These can also be used as biodiesel fuel.[1]

There are four methods of grinding coffee for brewing: burr-grinding, chopping, pounding, and roller grinding.

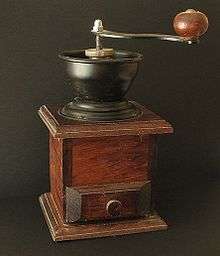

Burr-grinding

Burr mills use two revolving abrasive elements, such as wheels or conical grinding elements, between which the coffee beans are crushed or "torn" with little frictional heating. The process of squeezing and crushing of the beans releases the coffee's oils, which are then more easily extracted during the infusion process with hot water, making the coffee taste richer and smoother.

Both manually and electrically powered mills are available. These mills grind the coffee to a fairly uniform size determined by the separation of the two abrasive surfaces between which the coffee is ground; the uniform grind produces a more even extraction when brewed, without excessively fine particles that clog filters.

These mills offer a wide range of grind settings, making them suitable to grind coffee for various brewing systems such as espresso, drip, percolators, French press, and others. Many burr grinders, including almost all domestic versions, are unable to achieve the extremely fine grind required for the preparation of Turkish coffee; traditional Turkish hand grinders are an exception.

Chopping

Coffee beans can be chopped by using blades rotating at high speed (20,000 to 30,000 rpm), either in a blade grinder designed specifically for coffee and spices, or in a general use home blender. Devices of this sort are cheaper than burr grinders, but the grind is not uniform and will produce particles of widely varying sizes, while ideally all particles should have the same size, appropriate for the method of brewing. Moreover, the particles get smaller and smaller during the grinding process, which makes it difficult to achieve a consistent grind from batch to batch. The ground coffee is also warmed by friction. But any heating effect is negligible if grinding only enough beans for a few cups of coffee by this method because the process is over in less than ten seconds.

Blade grinders create “coffee dust” that can clog up sieves in espresso machines and French presses, and are best suited for drip coffee makers. They are not recommended for grinding coffee for use with pump espresso machines.

Pounding

Arabic coffee and Turkish coffee require that the grounds be almost powdery in fineness, finer than can be achieved by most burr grinders. Pounding the beans with a mortar and pestle can pulverize the coffee finely enough.

Roller grinding

In a roller grinder, the beans are ground between pairs of corrugated rollers. A roller grinder produces a more even grind size distribution and heats the ground coffee less than other grinding methods. However, due to their size and cost, roller grinders are used exclusively by commercial and industrial scale coffee producers.

Water-cooled roller grinders are used for high production rates as well as for fine grinds such as Turkish and espresso.

Brewing

Coffee can be brewed in several different ways, but these methods fall into four main groups depending on how the water is introduced to the coffee grounds: decoction (through boiling), infusion (through steeping), gravitational feed (used with percolators and in drip brewing), or pressurized percolation (as with espresso).

Brewed coffee, if kept hot, will deteriorate rapidly in flavor, and reheating such coffee tends to give it a "muddy" flavour, as some compounds that impart flavor to coffee are destroyed if this is done. Even at room temperature, deterioration will occur; however, if kept in an oxygen-free environment it can last almost indefinitely at room temperature, and sealed containers of brewed coffee are sometimes commercially available in food stores in America or Europe, with refrigerated bottled coffee drinks being commonly available at convenience stores and grocery stores in the United States. Canned coffee is particularly popular in Japan and South Korea.

Electronic coffee makers boil the water and brew the infusion with little human assistance and sometimes according to a timer. Some such devices also grind the beans automatically before brewing.

Boiling

Boiling, or decoction, was the main method used for brewing coffee until the 1930s[2] and is still used in some Nordic and Middle Eastern countries.[3] The aromatic oils in coffee are released at 96 °C (205 °F), which is just below boiling, while the bitter acids are released when the water has reached boiling point.[4]

The simplest method is to put the ground coffee in a cup, pour hot water over it and let cool while the grounds sink to the bottom. This is a traditional method for making a cup of coffee that is still used in parts of Indonesia. This method, known as "mud coffee" in the Middle East owing to an extremely fine grind that results in a mud-like sludge at the bottom of the cup, allows for extremely simple preparation, but drinkers then have to be careful if they want to avoid drinking grounds either from this layer or floating at the surface of the coffee, which can be avoided by dribbling cold water onto the "floaters" from the back of a spoon. If the coffee beans are not ground finely enough, the grounds do not sink.

"Cowboy coffee" is made by heating coarse grounds with water in a pot, letting the grounds settle and pouring off the liquid to drink, sometimes filtering it to remove fine grounds. While the name suggests that this method was used by cowboys, presumably on the trail around a campfire, it is used by others; some people prefer this method.

The above methods are sometimes used with hot milk instead of water.

Turkish coffee (aka Arabic coffee, etc.), a very early method of making coffee, is used in the Middle East, North Africa, East Africa, Turkey, Greece, the Balkans, and Russia. Very finely ground coffee, optionally sugar, and water are placed in a narrow-topped pot, called an cezve (Turkish), kanaka (Egyptian), briki (Greek), džezva (Štokavian) or turka (Russian) and brought to the boil then immediately removed from the heat. It may be very briefly brought to the boil two or three times. Turkish coffee is sometimes flavored with cardamom, particularly in Arab countries. The resulting strong coffee, with foam on the top and a thick layer of grounds at the bottom, is drunk from small cups.

Steeping

A cafetière, or French press, is a tall, narrow cylinder with a plunger that includes a metal or nylon fine mesh filter. The grounds are placed in the cylinder, and off-the-boil water is then poured into it. The coffee and hot water are left in the cylinder for a few minutes (typically 4–7 minutes) and then the plunger is gently pushed down, leaving the filter immediately above the grounds, allowing the coffee to be poured out while the filter retains the grounds. Depending on the type of filter, it is important to pay attention to the grind of the coffee beans, though a rather coarse grind is almost always called for.[5] A plain glass cylinder may be used, or a vacuum flask arrangement to keep the coffee hot; this is not to be confused with a vacuum brewer—see below.

A recent variation of the French press is the SoftBrew method. The grounds are placed in the cylindrical filter, which is then placed inside the pot, and very hot to boiling water is then poured into it. After waiting a few minutes, the coffee can then be poured out, with the grounds staying inside the metal filter.

Coffee bags are less often used than tea bags. They are simply disposable bags containing coffee; the grounds do not exit the bag as it mixes with the water, so no extra filtering is required.

Malaysian and some Caribbean and South American styles of coffee are often brewed using a "sock," which is actually a simple muslin bag, shaped like a filter, into which coffee is loaded, then steeped in hot water. This method is especially suitable for use with local-brew coffees in Malaysia, primarily of the varieties Robusta and Liberica which are often strong-flavored, allowing the ground coffee in the sock to be reused.

A vacuum brewer consists of two chambers: a pot below, atop which is set a bowl or funnel with its siphon descending nearly to the bottom of the pot. The bottom of the bowl is blocked by a filter of glass, cloth or plastic, and the bowl and pot are joined by a gasket that forms a tight seal. Water is placed in the pot, the coffee grounds are placed in the bowl, and the whole apparatus is set over a burner. As the water heats, it is forced by the increasing vapor pressure up the siphon and into the bowl where it mixes with the grounds. When all the water possible has been forced into the bowl the infusion is allowed to sit for some time before the brewer is removed from the heat. As the water vapor in the lower pot cools, it contracts, forming a partial vacuum and drawing the coffee down through the filter.

Filtration methods

Drip brew coffee, also known as filtered coffee, is made by letting hot water drip onto coffee grounds held in a coffee filter surrounded by a filter holder or brew basket. Drip brew makers can be simple filter holder types manually filled with hot water, or they can use automated systems as found in the popular electric drip coffee-maker. Strength varies according to the ratio of water to coffee and the fineness of the grind, but is typically weaker in taste and contains a lower concentration of caffeine than espresso, though often (due to size) more total caffeine.[6] By convention, regular coffee brewed by this method is served by some restaurants in a brown or black pot (or a pot with a brown or black handle), while decaffeinated coffee is served in an orange pot (or a pot with an orange handle).

A variation is the traditional Neapolitan flip coffee pot, or Napoletana, a drip brew coffee maker for the stovetop. It consists of a bottom section filled with water, a middle filter section, and an upside-down pot placed on the top. When the water boils, the coffee maker is flipped over to let the water filter through the coffee grounds.

The common electric percolator, which was in almost universal use in the United States prior to the 1970s, and is still popular in some households today, differs from the pressure percolator described above. It uses the pressure of the boiling water to force it to a chamber above the grounds, but relies on gravity to pass the water down through the grounds, where it then repeats the process until shut off by an internal timer. Some coffee aficionados hold the coffee produced in low esteem because of this multiple-pass process. Others prefer gravity percolation and claim it delivers a richer cup of coffee in comparison to drip brewing.

Indian filter coffee uses an apparatus typically made of stainless steel. There are two cylindrical compartments, one sitting on top of the other. The upper compartment has tiny holes (less than ~0.5 mm). And then there is the pierced pressing disc with a stem handle, and a covering lid. The finely ground coffee with 15–20% chicory is placed in the upper compartment, the pierced pressing disc is used to cover the ground coffee, and hot water is poured on top of this disk. Unlike the regular drip brew, the coffee does not start pouring down immediately. This is because of the chicory, which holds on to the water longer than just the ground coffee beans can. This causes the beverage to be much more potent than the American drip variety. 2–3 teaspoonfuls of this decoction is added to a 100–150 ml milk. Sugar is then sometimes added by individual preference.

Another variation is cold brew coffee, sometimes known as "cold press." Cold water is poured over coffee grounds and allowed to steep for eight to twenty-four hours. The coffee is then filtered, usually through a very thick filter, removing all particles. This process produces a very strong concentrate which can be stored in a refrigerated, airtight container for up to eight weeks. The coffee can then be prepared for drinking by adding hot water to the concentrate at a water-to-concentrate ratio of approximately 3:1, but can be adjusted to the drinker's preference. The coffee prepared by this method is very low in acidity with a smooth taste, and is often preferred by those with sensitive stomachs. Others, however, feel this method strips coffee of its bold flavor and character. Thus, this method is not common, and there are few appliances designed for it.

The amount of coffee used affects both the strength and the flavor of the brew in a typical drip-brewing filtration-based coffee maker. The softer flavors come out of the coffee first and the more bitter flavors only after some time, so a large brew will tend to be both stronger and more bitter. This can be modified by stopping the filtration after a planned time and then adding hot water to the brew instead of waiting for all the water to pass through the grounds.

In addition to the "cold press", there is a method called "Cold Drip Coffee". Also known as "Dutch Ice Coffee" (and very popular in Japan), instead of steeping, this method very slowly drips cold water into the grounds, which then very slowly pass through a filter. Unlike the cold press (which functions similar to a French Press) which takes eight to twenty-four hours, a Cold Drip process only takes about two hours, with taste and consistency results similar to that of a cold press.

Pressure

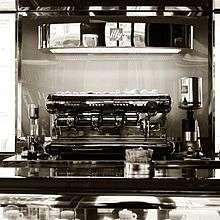

Espresso is made by forcing hot water at 91–95 °C (195–204 °F) under a pressure of between eight and eighteen bars (800–1800 kPa, 116–261 psi), through a lightly packed matrix, called a "puck," of finely ground coffee. The 30–60 cc (1–2 oz.) beverage is served in demitasse cups; sugar is often added. It is consumed during the day at cafes and from street vendors, or after an evening meal. It is the basis for many coffee drinks. It is one of the most concentrated forms of coffee regularly consumed, with a distinctive flavor provided by crema, a layer of flavorful emulsified oils in the form of a colloidal foam floating on the surface, which is produced by the high pressure. Espresso is more viscous than other forms of brewed coffee.

The moka pot, also known as the "Italian coffeepot" or the "caffettiera," is a three-chamber design which boils water in the lower section. The generated steam pressure, about one bar (100 kPa, 14.5 psi), forces the boiling water up through coffee grounds held in the middle section, separated by a filter mesh from the top section. The resultant coffee (almost espresso strength, but without the crema) is collected in the top section. Moka pots usually sit directly on a stovetop heater or burner. Some models have a transparent glass or plastic top.

Single-serving coffee machines force hot water under low pressure through a coffee pod composed of finely ground coffee sealed between two layers of filter paper or through a proprietary capsule containing ground coffee. Examples include the pod-based Senseo and Home Café systems and the proprietary Tassimo and Keurig K-Cup systems.

The AeroPress is another recent invention, which is a mechanical, non-electronic device where pressure is simply exerted by the user manually pressing a piston down with their hand, forcing medium-temperature water through coffee grounds in about 30 seconds (into a single cup.) This method produces a smoother beverage than espresso, falling somewhere between the flavor of a moka pot and a French Press.

Extraction

Proper brewing of coffee requires using the correct amount of coffee grounds, extracted to the correct degree (largely determined by the correct time), at the correct temperature.

More technically, coffee brewing consists of dissolving (solvation) soluble flavors from the coffee grounds in water. Specialized vocabulary and guidelines exist to discuss this, primarily various ratios, which are used to optimally brew coffee. The key concepts are:[7]

- Extraction

- Also known as "solubles yield" – what percentage (by weight) of the grounds are dissolved in the water.

- Strength

- Also known as "solubles concentration", as measured by Total Dissolved Solids – how concentrated or watery the coffee is.

- Brew ratio

- The ratio of coffee grounds (mass, in grams or ounces) to water (volume, in liters or half-gallons): how much coffee is used for a given quantity of water.

These are related as follows:

- Strength ∝ Brew ratio × Extraction

which can be analyzed as the following formula:

- dissolved solids/water = grounds/water × dissolved solids/grounds

A subtler issue is which solubles are dissolved – this depends both on solubility of different substances at different temperatures, and changes over the course of extraction. Different substances are extracted during the first 1% of brewing time than in the period from 19% extraction to 20% extraction. This is primarily affected by temperature.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Brewing guidelines are summarized by Brewing Control Charts which graph these elements, and center around an "ideal" rectangle indicating the target brewing range. The yield in the horizontal (x-axis), the strength is the vertical (y-axis), and a given brewing ratio determines a radial line, since for a giving brewing ratio the strength is directly proportional to the yield.

Ideal yield is widely agreed to be 20±2% (18–22%), while ideal strength for brewed coffee varies. American standards for "ideal strength" are generally considered to be between 1.25±0.10% (1.15–1.35%), while Norwegian standards are about 1.40±0.10% (1.30–1.50%). European standards fall in the middle range at 1.20–1.45%.

These are most easily achieved with a brewing ratio of 55 g/L (55 grams of coffee per litre of water) for American standards, to 63 g/L in Norwegian standards, yielding approximately 14–16 grams of coffee for a standard 240 ml (8.1 US fl oz) cup. These guidelines apply regardless of brewing method, with the following exceptions:

- Espresso is significantly different – it is much stronger, and has more varied extraction. Seven grams of grounds are used to make a 25-ml shot of espresso (this comes to 280 g/L, but the amount of water used is actually more than 25 ml because some stays with the grounds). Espresso has about 212 mg caffeine per 100 g as compare to around 40 mg per 100 g of normal coffee.[11]

- Dark roast coffee tastes subjectively stronger than medium roasts. Standards are based on medium roasts, and the equivalent strength for a dark roast requires using a lower brewing ratio.

Separation

Coffee in all these forms is made with roasted and ground coffee and hot water, the used grounds either remaining behind or being filtered out of the cup or jug after the main soluble compounds have been extracted. The fineness of grind required differs for the various brewing methods.

Gallery of common brewing methods

Pressure:

-

Home espresso machine without pump (only with steam pressure)

-

Home espresso machine with pump

-

Commercial espresso machine

Gravity and steeping:

-

Electric drip brewer

-

Cafetière/French press

-

Preparation of Vietnamese iced coffee

Instant coffee

Instant coffee is made commercially by drying prepared coffee; the resulting soluble powder is dissolved in hot water by the user, and sugar/sweeteners and milk or creamers are added as desired.

Another way to enjoy instant coffee is "without water". This consists of boiling the milk or the liquid creamer, then adding the instant coffee and the sweetener to taste.

Presentation

- Also see the article Coffee culture.

Hot drinks

Espresso-based, without milk

- Espresso: see above under heading Pressure.

- Ristretto is an espresso drink where the weight of the ground coffee is equal to the weight of the brewed shots. The result is a "shorter" shot that is sweeter and more flavorful.

- Bica is a Portuguese espresso, longer than its Italian counterpart, but a little bit softer in taste. This is due to the fact that Portuguese roasting is slightly lighter than the Italian one. "Bica" is thus similar to "Lungo" in Italy.

- Lungo is different from an Americano. It is a "longer" espresso run through the machine; all the water runs through the beans, as opposed to adding water. With Italian roasting it extracts more bitter flavours.

- Americano style coffee is made with espresso (one or several shots), with hot water then added to give a similar strength (but different flavor) to drip-brewed coffee.

- Long black is similar to Americano, but prepared in different order (a double shot of espresso is added to water instead of vice versa); most common in Australia and New Zealand.

Espresso-based, with milk

- Caffè breve is an American variation of a latte: a milk-based espresso drink using steamed half-and-half (light - 10 per cent - cream) instead of milk.

- Caffè latte or caffè e latte is often called simply latte, which is Italian for "milk", in English-speaking countries; it is espresso with steamed milk, traditionally topped with froth created from steaming the milk. A latte comprises one-third espresso and nearly two-thirds steamed milk. More frothed milk makes it weaker than a cappuccino. A latte is also commonly served in a tall glass; if the espresso is slowly poured into the frothed milk from the rim of the glass, three layers of different shades will form, with the milk at the bottom, the froth on top and the espresso in between. A latte may be sweetened with sugar or flavored syrup. Caramel and vanilla and other flavors are used.

- Caffè macchiato, sometimes Espresso macchiato or "short" macchiato — macchiato meaning "marked" — is an espresso with a little steamed milk added to the top, usually 30–60 ml (1.0–2.0 US fl oz), sometimes sweetened with sugar or flavored syrup. A "long" macchiato is a double espresso with a little steamed milk. This differs from a latte macchiato which is milk "marked" with espresso. A macchiatto may be 'traditional' or 'topped up' (extra milk added) depending on strength preferences.

- Cappuccino comprises equal parts of espresso coffee and milk and froth, sometimes sprinkled with cinnamon or powdered cocoa.

- Flat white is one part espresso with two parts steamed milk, usually served in a cappuccino cup with the foam decorated with a motif (e.g., fern or heart). This is a speciality of Australia and New Zealand.

- Galão is a Bica (Portuguese espresso) to which is added hot milk, tapped from a canister and sprayed into the glass in which it is served.

- Latte macchiato is the inverse of a caffè macchiato, being a tall glass of steamed milk spotted with a small amount of espresso, sometimes sweetened with sugar or syrup.

- Mocha is a latte with chocolate added.

- Café con leche is espresso with steamed milk ("leche" is Spanish for "milk"), usually half coffee and half milk, similar to latte but less frothy.

- Cortado is espresso with a small amount of very lightly foamed milk added, in contrast to a macchiato's more frothy texture. In Spain when served with condensed milk, this is called "cafe con leche condensada", or "Bombon".

Brewed or boiled, non espresso-based

- Black coffee is drip-brewed, percolated, vacuum brewed, or French-press-style coffee served without cream. Some persons who drink coffee this way add sugar to it.

- White coffee is black coffee with unheated milk or creamer added to it; this is the most popular way of drinking coffee in the United States. Some persons who drink coffee this way add sugar to it. (Note: though having a similar term, this is not to be confused with the Beirut herbal tea from Lebanon or the Malaysian Ipoh white coffee.)

- Café au lait is similar to latte except that drip-brewed coffee is used instead of espresso, with an equal amount of milk.

- Kopi tubruk is an Indonesian-style coffee similar in presentation to Turkish coffee. However, kopi tubruk is made from coarse coffee grounds, and is boiled together with a solid lump of sugar. It is popular on the islands of Java and Bali and their surroundings.

- Indian filter coffee, particularly common in southern India, is prepared with rough-ground dark roasted coffee beans (e.g., Arabica, PeaBerry), and chicory. The coffee is drip-brewed for a few hours in a traditional metal coffee filter before being served with milk and sugar. The ratio is usually 1/4 decoction, 3/4 milk.

- Greek coffee is prepared similarly to Turkish coffee. The main difference is that the coffee beans are ground into a finer powder and sugar is added during the process. It does not contain other flavors, and is usually served without milk. Greek coffee is served in a small cup with a handle, sometimes accompanied by a small cookie, and always with a glass of water. A similar method to the Greek preparation is used in Colombia to make "tinto," strong black coffee that is often brewed with panela, a sugarcane juice concentrate in cake form. A muslin or fine-cloth bag is used to strain the grounds.

- Indochinese-style coffee is another form of drip brew. In this form, hot water is allowed to drip though a metal mesh into a cup, and the resulting strong brew is poured into a glass containing sweetened condensed milk which may contain ice. Due to the high volume of coffee grounds required to make strong coffee in this fashion, the brewing process is quite slow. It is highly popular in Laos, Vietnam and Cambodia.

Fortified coffee

- Red Eye is one espresso shot added to a cup of coffee (typically 210-480 ml, 7-16 oz). Some add milk or sugar.

- Black Eye is two espresso shots added to a cup of coffee (typically 210-480 ml, 7-16oz). Some add milk or sugar.

Flavored coffees

- Flavored coffee: In some cultures, flavored coffees are common. Chocolate is a common additive that is either sprinkled on top or mixed with the coffee to imitate the taste of Mocha. Other flavorings include spices such as cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom, or Italian syrups. In the Maghreb, the orange blossom is used as a flavoring. Vanilla- and hazelnut-flavored coffees are common in the United States; these are usually artificially flavored.

- Turkish coffee is served in very small cups about the size of those used for espresso. Traditional Turkish coffee cups have no handles, but modern ones often do. The crema or "face" is considered crucial, and since it requires some skill to achieve its presence is taken as evidence of a well-made brew. (See above for preparation method.) It is usually made sweet, with sugar added after the brew process begins, and often is flavored with cardamom or other spices. In many places it is customary to serve it with a tall glass of water on the side.

- Chicory is sometimes combined with coffee as a flavoring agent, as in the style of coffee served at the famous Café du Monde in New Orleans. Chicory has historically been used as a coffee substitute when real coffee was scarce, as in wartime. Chicory is popular as an additive in Belgium and is an ingredient in Madras filter coffee.

Alcoholic coffee drinks

Alcoholic spirits and liqueurs can be added to coffee, often sweetened and with cream floated on top. These beverages are often given names according to the alcoholic addition:

- Black coffee with brandy, or marc, or grappa, or other strong spirit.

- Irish coffee, with Irish whiskey, sugar, and cream. There are many variants, essentially the same but with the use of a different spirit:

- Café au Drambuie, with Drambuie instead of whiskey

- Caribbean or Jamaican coffee, with dark rum; a similar drink exists in northern Germany, called Pharisäer

- Gaelic or Scotch coffee, with Scotch whisky

- Kahlúa coffee, with Kahlúa coffee liqueur

- Café royal, with a flambéd and slightly caramelized teaspoonful of sugar and cognac

- Kaffekask, a Swedish variant where some coffee is added to a cup of brännvin

Cold drinks

- Iced coffee is a cold version of hot coffee, typically drip or espresso diluted with ice water. Iced coffee can also be an iced or chilled form of any drink in this list. In Australia, iced coffee is cold milk flavoured with a small amount of coffee, often topped with ice cream and/or whipped cream, and served in a tall glass.

- Frappé is a strong cold coffee drink made from instant coffee and in Greece it is consumed more than the Turkish coffee (which the Greeks refer to as "elliniko" or "greek" after the Greek-Turkish dispute over Cyprus in 1974). Frappé was created in Greece in 1957 in the city of Thessaloniki when a businessman taking part in the open, international trade exhibition there, couldn't wait for hot water for his coffee. His idea spread instantly to all Greece. Preparation: one spoonful of instant coffee (and sugar if one wishes) in a shaker with some water (and milk). It is shaken hard enough for one minute, then icecubes are added and it is served with a drinking straw because of the "foam" that is produced.

- Ice-blended coffee (trade names: Frappuccino, Ice Storm) is a variation of iced coffee. The name Frappucino (a portmanteau of frappé and cappuccino) was originally developed, named, trademarked and sold by George Howell's Eastern Massachusetts coffee shop chain, The Coffee Connection, which was purchased by Starbucks in 1994. Other coffeehouses serve similar concoctions, but under different names, since "Frappuccino" is a Starbucks trademark. One commonly used by many stores is Ice Storm. Another prominent example is the Javakula at Seattle's Best Coffee. A frappuccino is a latte, mocha, or macchiato mixed with crushed ice and flavorings (such as vanilla/hazelnut if requested by the customer) and blended.

- Thai iced coffee is a popular drink commonly offered at Thai restaurants in the United States. It consists of coffee, ice, and sweetened condensed milk.

- Igloo Espresso a regular espresso shot poured over a small amount of crushed ice, served in an espresso cup. Sometimes it is requested to be sweetened as the pouring over the ice causes the shot to become bitter. Originating in Italy and has migrated to Australian coffee shops.

- Cold brew coffee is a process of brewing coffee slowly (12 hours) with cold water to produce a strong coffee concentrate, often served diluted with water or milk of choice. A common commercial example is Toddy coffee, which is a drip system.

- Affogato is a cold drink, often served as dessert, consisting of a scoop of ice cream or gelato topped with an espresso shot. Often, the drinker is served the ice cream and espresso in separate cups, and will mix them at the table so as to prevent the ice cream from entirely melting before it can be consumed.

Confectionery (non-drinks)

- Chocolate-covered roasted coffee beans are available as a confection; eating them delivers more caffeine to the body than does drinking the same mass (or volume) of brewed coffee (ratios depend upon the brewing method) and has similar physiological effects, unless the beans have been decaffeinated.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kozlan, Melanie (August 3, 2010). "Fun Ways to Reuse Coffee Grinds". Four Green Steps. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2013.

- ↑ The Joy of Coffee, page 87, Corby Kummer,, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003, ISBN 0-618-30240-9

- ↑ The Joy of Coffee, page 88, Corby Kummer,, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003, ISBN 0-618-30240-9

- ↑ Camp Coffee, Terry Krautwurst, Backpacker Magazine, February 1991

- ↑ How to Use a Press Pot Mark Prince, November 11, 2003. coffeegeek.com

- ↑ McCusker, Rachel R.; Goldberger, Bruce A.; Cone, Edward J. (2003-10-27). "Caffeine Content of Specialty Coffees". J Anal Toxicol 27 (7). doi:10.1093/jat/27.7.520. PMID 14607010.

- ↑ (Lingle 1995)

- ↑ Brewing -- the American Standard

- ↑ Brewing -- the European Standard

- ↑ Brewing -- the Norwegian Coffee Association Standard

- ↑ Coffee, brewed, espresso, restaurant-prepared and Coffee, brewed from grounds, prepared with tap water, in the USDA National Nutrient Database

References

- Lingle, Ted R. (1995), The Coffee Brewing Handbook (First ed.), Specialty Coffee Association of America

- Brewing -- How to Get the Most Out of Your Coffee, Mountain City Coffee Roasters

External links

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||