Cochlear implant

| Cochlear implant | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

Cochlear implant | |

| MedlinePlus | 007203 |

A cochlear implant (CI) is a surgically implanted electronic device that provides a sense of sound to a person who is profoundly deaf or severely hard of hearing.

Cochlear implants may help provide hearing in patients who are deaf because of damage to sensory hair cells in their cochleas. These sensory cells never regenerate, unlike most cells in the body. Cochlear implants replace the input of those lost or damaged hair cells to replicate the different frequencies and amplitudes of sound. Implants can augment hearing sufficiently to improve understanding of speech and environmental sounds, although the quality of sound is different from natural hearing and the input subject to different neural regulation. Newer devices and processing strategies allow recipients to hear better in noise, enjoy music, and even use their implant processors while swimming.

As of December 2012, approximately 324,000 people worldwide have surgically implanted cochlear implants; in the U.S., roughly 58,000 adults and 38,000 children are recipients.[1] Some recipients have bilateral implants to allow for stereo sound. However, barriers such as the cost of the device prevent many patients from acquiring the device. Long-term auditory therapy following implantation is often required for patients to accurately interpret the soundwaves from the device.

History

Introduction

Any history of the cochlear implant must start with an overview[2] of non-surgical treatments proposed in the eighteenth century to overcome the social and psychological consequences of total neonatal deafness. The story begins in the early eighteenth century. Although the Frenchman Abbé de l’Épée [3] (1712-1759) did not actually invent sign language, he did at least bring together the results of various experiences, notably those in Spain, before standardizing and teaching this method with the aim of facilitating communication among all those who practise it, whether deaf or not. Abbé de l’Épée was the first to use sign language to promote the mental development and education of deaf children. In the middle of the eighteenth century he created a free public school, which survived the French Revolution and was perpetuated by the nascent Republic in the form of the National Institute for Deaf-Mutes (Institution nationale des sourds-muets). This institute, now called the National Institute for Young Deaf People (Institution Nationale des Jeunes Sourds), has always been located in rue St Jacques, Paris. For many years it was recognized internationally as a leader in the education of deaf children, but its teachers and physicians disagreed on certain teaching methods: the teachers tended to prefer oralisation (difficult, owing to the lack of sensory feedback), while the physicians (notably Prosper Menière and Edouard Fournié) opted for sign language. In fact, this disagreement concerned not only communication itself but also the very place of deaf people in society: sign language favored the teaching and development of deaf people within their own community, while oralisation sought to integrate deaf people into the rest of society. Towards the end of the 19th century the development of international transport and the ENT (ear, nose and throat) medical discipline internationalized the debate.

Early cochlear implants in adolescents and adults who had been deaf since birth met with failure, often abandoned by their users. These failures largely accounted for the widespread opposition of the deaf community to this new therapeutic approach. Animal experiments[4] subsequently showed that the auditory system could mature with chronic cochlear implant stimulation,[5] but only if they started to be stimulated within an early period after birth.[6] Early cochlear implantation in children and the corresponding maturational processes ignited in their brains support such concept.[7]

Electrical stimulation of afferent auditory pathways became feasible in the last half of the twentieth century. Chronologically, its development can be divided into three periods:

- basic research and early human trials (1957-1975)

- development of multichannel implants in four countries (France, Austria, Australia and the United States), ending in a consensus on the best approach (1976-1997)

- the modern era

Basic research

In 1961, G von Bekesy (1899-1972) received the Nobel Prize for demonstrating that sounds trigger vibrations of the basilar membrane which spread from the base to the apex of the cochlea in the form of longitudinal waves; peaks occur at various points depending on the frequency, resembling the keys of a piano, with low frequencies towards the apex and high frequencies towards the oval window. The terms "cochlear keyboard" and “cochlear tonotopy” are often used to describe these phenomena.

In 1968, H. Davis described the physiology of auditory receptors.[8]

In 1972, NY Kiang unraveled the physiology of electrical stimulation of the inner ear.[9]

In 1975, EF Evans showed that each sensory afferent fiber of the cochlear nerve handles a specific frequency, making it electively sensitive to a very narrow frequency band.[10]

First human trials: grandeur and limitations of the single-channel implant

In 1957, A. Djourno, a Parisian professor of medical physics, and C. Eyries, a Parisian otologist, restored hearing to a deaf patient with total bilateral cholesteatomas by electrically stimulating acoustic nerve fibers still present in the inner ear. This result was fortuitous, however: Djourno and Eyries had in fact been seeking to remobilize the frozen facial traits of a patient with cholesteatomas in both ears, which had been complicated, probably many years previously, by bilateral facial paralysis. They failed in their primary goal but had the wherewithal to record their electro-acoustic observations over several weeks and to publish them in the French journal Presse Médicale.[11] They stopped their experiment when the apparatus broke down after less than a month.

If these French researchers had not noted their unexpected findings, William House might never have dared try to compensate total deafness, which is all the more severe when bilateral.

In 1961, a patient gave William House,[12] a Californian otologist, a copy of a Los Angeles Times article[13] describing the work of the Paris researchers. House had already transformed the functional outcome of cerebellopontine angle surgery by making use of the first surgical microscopes developed in the late 1950s, and was familiar with total deafness. He resumed his research, basing his indications on what was known at the time about the physiology of hearing, a rapidly progressing field, at least in animals. House standardized the surgical procedure and stably positioned the stimulatory electrode by threading it through the round window in the cochlear channel. He encountered a number of difficulties, especially in sealing the implant. Solutions emerged with the advent of pacemakers, but it took House almost ten years to develop a single-channel cochlear implant. This ultimately robust and simple device stimulated the whole set of the auditory nerve fibers simultaneously, meaning that the recipient was able to recognize only the rhythms of the speech.

House marketed his device jointly with J. Urban[14] and continued to implant it until at least 1965. The system was sufficiently reliable for researchers and otologists to overlook its mediocre functional performance.

In 1966 B. Simmons (Palo Alto, CA)[15] performed the first temporary human implantation of a multichannel system in the trunk of the auditory nerve itself, in a deaf volunteer. This experimental work showed that stimulation of limited quotas of the auditory nerve fibers generated sensations of different frequencies depending on the origin of the stimulated fibers on the cochlear keyboard. Shortly afterwards, Mr. Merzenich (UCSF - San Francisco)[16] confirmed these findings in macaques, using a different approach.

In 1967, G. Clark in Melbourne[17] created a team to conduct basic research on the pathophysiology of profound deafness in animals and on the tolerability of implanted materials.

In 1973, R. Michelson (UCSF - San Francisco)[18] chronically implanted a deaf man with an experimental multichannel implant: this device used pairs of antennas for each channel, one transmitting and one receiving. It was possible to measure several parameters and to test various types of stimulation, including both bipolar and unipolar.

In 1973, CH Chouard had extensive personal experience of petrous bone surgery involving the vestibular and facial nerves.[19][20] Together with P. MacLeod, a close friend specializing in sensory physiology, Chouard decided to create a multidisciplinary team at the ENT Research Laboratory of St-Antoine teaching hospital in Paris.[21] In 1975 the two men showed, in several patients with total unilateral traumatic deafness and facial paralysis,[22] that electrical stimulation of 8 to 12 electrodes, isolated from one another and placed in different parts of the scala tympani, allowed the recipients to perceive different frequencies.

Then, having developed a test to ensure that auditory fibers were still present and functional (based on electrical stimulation of the round window), the Paris team implanted their electrodes in patients with long-standing total bilateral deafness. After a relatively brief period of postoperative speech therapy, all the patients were able to recognize a variable percentage of words without lip-reading.[23] Under the scientific direction of P. Mac Leod, industrial production of an implantable functional device was entrusted to the Bertin, a French company. A table-top prototype was quickly built, but the untimely death of Jean Bertin in late 1975 led to restructuring of the company, and it was only in the summer of 1976 that the French researchers finally received the first 6 devices.

In the meantime, other French teams launched their own research programs, particularly in the area of the electrodes bearer, but they were forced to abandon their efforts.[24][25][26]

In 1975, K. Burian[27] in Vienna, building on the long tradition of the Viennese ENT school, launched the development of the first Austrian implant. His work on single-channel intra- and extra-cochlear stimulation, and then on multichannel stimulation, was pursued by his pupil I. Hochmair-Desoyer and her husband Professor Hochmair of Innsbruck. Their work culminated in 1982 with the Austrian Med-el implant.

Technological evolution and competition leading to a consensus on the best approach (1976-1997)

The first implant took place at Saint-Antoine hospital, Paris, on Wednesday 22 September 1976. It was performed by CH Chouard, assisted by Bernard Meyer. The patient recovered his hearing the following day, and another 5 patients were quickly implanted despite the bulky nature of the transmitter. On 16 March 1977, Bertin filed Patent No. 77/07824, based on the physiological criteria of MacLeod and making two simultaneous claims: 1) sequential transmission to the cochlea of an indeterminate number of frequency bands, and 2) transmission of all the sound information. The first results were presented at the XIth World ENT Conference in Buenos Aires, and were quickly published.[28][29]

For nearly twenty years, this document influenced all the procedures and approaches used by other international teams, who were obliged to find ways around the patent claims, usually by opting to transmit only a portion of the speech information, until the patent fell into the public domain in 1997.

On 3 November 1977, the team of G. Clark (Australia) filed a patent for a system with three functional electrodes but using only a limited part of the speech information (voicing and one of the two formants of the vowels).

In 1975, Ingeborg and Erwin Hochmair started cochlear implant development at the Technical University of Vienna. 1977 the world’s first microelectronic multi-channel cochlear implant developed by Ingeborg and Erwin Hochmair was implanted in Vienna by Prof. Kurt Burian (1924 – 1996). The implant had 8 channels, a stimulation rate of 10.000 pulses per second per channel and 8 independent current sources and flexible electrode for 22–25 mm insertion into the cochlea. Prof. Kurt Burian inserted the flexible electrode through the round window into the scala tympani.[30]

In December 1977, the Austrian team implanted a multichannel system with sufficient flexibility to study responses to various manipulations of the sound signal.[31]

September 1978 saw the first International Teaching Seminar on Cochlear Implants held in Paris and attended by representatives of the other three involved countries, namely I. Hochmair-Desoyer and E. Hochmair (Austria), J. Patrick (Australia), R. Michelson and R. Schindler (USA).

In 1978, Graeme Clark (Australia) implanted his first patient.[32]

In fall of 1979 a patient implanted in August 1979 with a device by Ingeborg and Erwin Hochmair, received a small body worn speech processor. It was modified in March 1980 at which time the patient became the first person to show open set speech understanding without lip-reading using a portable processor.[30]

In 1982, CH Chouard, employing the Born reconstruction technique which he had previously used in his neuroanatomical research together with C. Eyries,[33] was the first to demonstrate in animals[4] the need for early implantation to avoid the atrophy of the central auditory structures that occurs very rapidly in case of persistent neonatal deafness.

In 1982 the new Bertin device, Chorimac 12, was presented. It had 12 electrodes and a smaller transmitter but was still much larger than the Australian and Austrian devices. A few years later, after announcing the arrival of the all-digital device[34] that Chouard and MacLeod had been demanding since 1980, Bertin abandoned the field and sold its license to another French Company, MXM-Neurelec, in 1987. Bertin filed for bankruptcy in 1998.

In 1983, the 2nd international conference on cochlear implants was held in the former Paris Faculty of Medicine, just before the annual meeting of the international ENT collegium (ORLAS).

In 1984, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the Australian implant for use in adults.

In 1985, the Australians improved on their original device35, which now transmitted all the vowel information.[35]

In 1990, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the Australian implant for young children.

In 1990, Ingeborg and Erwin Hochmair started their company Med-el based in Innsbruck, Austria and hired their first employees. One year later the company presented the world’s first behind-the-ear audio processor.[36]

In 1991, MXM-Neurelec presented their first multichannel implant based on the Bertin license. It was fully digitized and could be adapted to an ossified cochlea.[37]

From 1992 onwards, the multichannel cochlear implant gradually gained acceptance in France. Other teams, first in Montpellier[38][39] and Toulouse, begin to implant it. At the same time, the sound processing strategy used by the different cochlear implants gradually adopted technology resembling that described in the Bertin patent, delivering all the sound information in a sequential manner. The American implant too provided the entire information in this way, while avoiding falling foul of the French patent by employing a few clever tricks and restrictions. The Australian device was also improved, providing all the sound information but retaining only the channels containing the maximum energy. This restriction also avoided the Bertin patent claims.[40]

In 1994, Med-el presented the world’s first electrode array capable of stimulating the entire length of the cochlea to allow a more natural hearing.[41]

In 1995, Paris organized the 3rd International Conference on Cochlear Implants.[42]

1996, Med-el presented the world’s first miniaturised multichannel implant (4 mm thin) and also had the first bilateral implantation for the purpose of binaural hearing.[41]

In 1997, the French license was blatantly copied, leading to Bertin to bring a lawsuit with seizure of the apparatus in question. This was just before the patent fell into the public domain. However, the charges were quickly dropped following protests in some surgical centers. In addition, the cost of the legal proceedings far exceeded any financial retribution the company could expect to obtain.[43]

All manufacturers have since applied the principles of the Bertin patent defined by P. Mac Leod and CH Chouard.[44]

Present

Following the French National Ethics Committee's[45] approval of screening in the early neonatal period, and the tercentenary of the work of Abbe de l'Épée,[46] celebrated in 2012 at the initiative of Legent, the positions of the deaf and hearing communities in France have started to be reconciled. In a cordial and respectful dialogue, avoiding proselytism, the two communities are striving to refine the criteria of choice between the cochlear implant and the use of sign language.[47] Both options are sometimes valid.

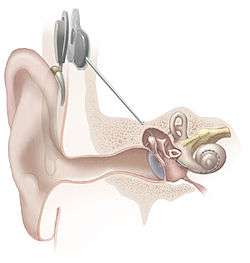

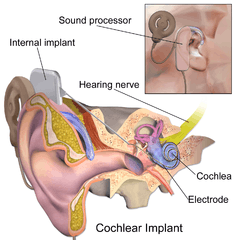

Parts of the cochlear implant

The implant is surgically placed under the skin behind the ear. The basic parts of the device include:

- External:

- one or more microphones which picks up sound from the environment

- a speech processor which selectively filters sound to prioritize audible speech, splits the sound into channels and sends the electrical sound signals through a thin cable to the transmitter,

- a transmitter, which is a coil held in position by a magnet placed behind the external ear, and transmits power and the processed sound signals across the skin to the internal device by electromagnetic induction,

- Internal:

- a receiver and stimulator secured in bone beneath the skin, which converts the signals into electric impulses and sends them through an internal cable to electrodes,

- an array of up to 22 electrodes wound through the cochlea, which send the impulses to the nerves in the scala tympani and then directly to the brain through the auditory nerve system. There are 4 manufacturers for cochlear implants, and each one produces a different implant with a different number of electrodes. The number of channels is not the sole basis upon which a manufacturer is chosen; the signal processing algorithm is another important consideration.

Candidates

A number of factors determine the degree of success to expect from the operation and the device itself. Cochlear implant centers determine implant candidacy on an individual basis and take into account a person's hearing history, cause of hearing loss, amount of residual hearing, speech recognition ability, health status, and family commitment to aural habilitation/rehabilitation.

A prime candidate is described as:

- having severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss in both ears.

- having a functioning auditory nerve

- having lived at least a short amount of time without hearing (approximately 70+ decibel hearing loss, on average)

- having good speech, language, and communication skills, or in the case of infants and young children, having a family willing to work toward speech and language skills with therapy

- not benefiting enough from other kinds of hearing aids, including latest models of high-power hearing instruments and FM systems

- having no medical reason to avoid surgery

- having appropriate services set up for post-cochlear implant aural rehabilitation (through a speech language pathologist, a deaf educator, or an auditory verbal therapist).

Type of hearing loss

People with mild or moderate sensorineural hearing loss are generally not candidates for cochlear implantation. Their needs can often be met with hearing aids alone or hearing aids with an FM system. After the implant is put into place, sound no longer travels via the ear canal and middle ear but is picked up by a microphone and sent through the device's speech processor to the implant's electrodes inside the cochlea. Thus, most candidates have been diagnosed with a severe or profound sensorineural hearing loss.

The presence of auditory nerve fibers is essential to the functioning of the device: if these are damaged to such an extent that they cannot receive electrical stimuli, the implant will not work. Some individuals with severe auditory neuropathy may also benefit from cochlear implants.

Age of recipient

Post-lingually deaf adults, pre-lingually deaf children and post-lingually hard of hearing people (usually children) who have lost hearing due to diseases such as CMV and meningitis, form three distinct groups of potential users of cochlear implants with different needs and outcomes. Those who have lost their hearing as adults were the first group to find cochlear implants useful in regaining some comprehension of speech and other sounds. The outcomes of individuals that have been deaf for a long period of time before implantation are sometimes astonishing, although more variable.

The risk of surgery in the older patient must be weighed against the improvement in quality of life. As the devices improve, particularly the sound processor hardware and software, the benefit is often judged to be worth the surgical risk, particularly for the newly deaf elderly patient.[48]

Another group of customers is parents of children born deaf who want to ensure that their children grow up with good spoken language skills. The brain develops after birth and adapts its function to the sensory input; absence of this has functional consequences for the brain, and consequently congenitally deaf children who receive cochlear implants at a young age (less than 2 years) have better success with them than congenitally deaf children who first receive the implants at a later age,[49] though the critical period for utilizing auditory information does not close completely until adolescence. One doctor has said, "There is a time window during which they can get an implant and learn to speak. From the ages of two to four, that ability diminishes a little bit. And by age nine, there is zero chance that they will learn to speak properly. So it’s really important that they get recognized and evaluated early."[50] Additionally, there is another sensitive period for strong asymmetry in hearing that closes earlier in life. In cases of early single-sided deafness or unilateral cochlear implantation, the brain reorganizes towards the hearing ear and that puts the deaf ear into a disadvantage.[51] Consequently, the benefit of a sequential second implantation (on the deaf ear) is critically dependent on the delay between implantations.[52] Periods of asymmetric hearing during early childhood should be avoided, and therapy of deafness should be binaural.

The third group who will benefit substantially from cochlear implantation are post-lingual subjects who have lost hearing: a common cause is childhood meningitis. Young children (under five years) in these cases often make excellent progress after implantation because they have learned how to form sounds and only need to learn how to interpret the new information in their brains.

Number of users

By the end of 2008, the total number of cochlear implant recipients had grown to an estimated 150,000 worldwide.[53] A story in 2000 stated that one in ten deaf children in the United States had a cochlear implant, and the projection was that the ratio would rise to one in three in ten years.[54]

Mexico had performed 55 cochlear implant operations by the year 2000 (Berruecos 2000). Taiwan and China announced an approximately $270 million order for cochlear implant devices for children in 2006, which are being paid for by major healthcare organization based in Taipei. These cochlear implants are a donation by the Taiwanese organization[55][56]

In India, there are an estimated 1 million profoundly deaf children, and about 5,000 have cochlear implants. This minuscule number is due to the high costs for the implant, as well as subsequent therapy.[57]

The operation, post-implantation therapy and ongoing effects

The device is surgically implanted under a general anesthetic or local anesthetic without or with sedation,[58] and the operation usually takes from 1½ to 5 hours. First a small area of the scalp directly behind the ear may be shaved and cleaned. Then an incision is made in the skin behind the ear and the surgeon drills into the mastoid bone, creating a pocket for the receiver/stimulator, and then into the inner ear where the electrode array is inserted into the cochlea. The patient normally goes home the same day or the day after the surgery, although some cochlear implant recipients stay in the hospital for 1 to 2 days. As with every medical procedure, the surgery involves a certain amount of risk; in this case, the risks include skin infection, onset of (or change in) tinnitus, damage to the vestibular system, and damage to facial nerves that can cause muscle weakness, impaired facial sensation, or, in the worst cases, facial paralysis. There is also the risk of device failure, usually where the incision does not heal properly. This occurs in 2% of cases and the device must be removed.

There is also a potential risk to lose the residual hearing the patient may have in the implanted ear because of the shaving of hair cells in the cochlea but the chances have decreased over time; as a result, some doctors advise single-ear implantation, saving the other ear in case a biological treatment becomes available in the future. However, with a careful surgical technique and a flexible electrode the residual hearing of the patient can be preserved. Ever since Ingeborg Hochmair and her husband Erwin Hochmair started their work this aspect has been one of the priorities.[36]

After 1–4 weeks of healing (the wait is usually longer for children than adults), the implant is "activated" by connecting an external sound processor to the internal device via a magnet. Initial results vary widely, and post-implantation therapy is required as well as time for the brain to adapt to hearing new sounds. In the case of congenitally deaf children, audiological training and speech therapy typically continue for years, though infants can become age appropriate—able to speak and understand at the same level as a hearing child of the same age. The participation of the child's family in working on spoken language development is considered to be even more important than therapy, because the family can aid development by participating actively—and continually—in the child's therapy, making hearing and listening interesting, talking about objects and actions, and encouraging the child to make sounds and form words. Professionals trained to work with children who have received cochlear implants are a major part of the parent-professional team when addressing the task of teaching children to use their hearing to develop speech and spoken language. These professionals include, but are not limited to:

- Speech-Language Pathologists (SLP)

- Certified Auditory-Verbal Therapists (LSLS Cert. AVT)

- Pediatric Audiologist (AuD)

- Teacher of the Deaf (ToD) with a specialization in Oral Deaf Education

Some users, audiologists, and surgeons also report that when there is an ear infection causing fluid in the middle ear, it can affect the cochlear implant, leading to temporarily reduced hearing.

The implant has a few effects unrelated to hearing. Manufacturers have cautioned against scuba diving due to the pressures involved, but the depths found in normal recreational diving appear to be safe. The external components generally need to be turned off and removed prior to swimming or showering, unless manufacturers specified that the external components are water proof. In most cases, certain diagnostic tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) cannot be used on patients with cochlear implants without first removing the small internal magnet (an outpatient procedure usually performed with a local anesthetic), but some implants are now FDA approved for use with certain strengths of MRI machine.

The company Med-el has tackled this issue and has launched in 2014, the implant SYNCHRONY (PIN). Users with this implant do not have to undergo multiple surgeries to remove and reinsert the magnet and consequently lose their hearing while the magnet is out to undergo a MRI of up to 3.0 Tesla (common strength of MRI nowadays).[59]

Large amounts of static electricity can cause the device's memory to reset. For this reason, children with cochlear implants are also advised to avoid plastic playground slides.[60] The electronic stimulation the implant creates appears to have a positive effect on the nerve tissue that surrounds it.[61]

Cost

In the United States, medical costs run from US$45,000 to US$125,000; this includes evaluation, the surgery itself, hardware (device), hospitalization and rehabilitation. Some or all of this may be covered by health insurance. In the United Kingdom, the NHS covers cochlear implants in full, as does Medicare in Australia, and the Department of Health[62] in Ireland, Seguridad Social in Spain and Israel, and the Ministry of Health or ACC (depending on the cause of deafness) in New Zealand. According to the US National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, the estimated total cost is $60,000 per person implanted.

A study by Johns Hopkins University determined that for a three-year-old child who receives cochlear implants can save $30,000 to $50,000 in special-education costs for elementary and secondary schools as they are more likely to be mainstreamed in school and thus use fewer support services than similarly deaf children.[63]

Efficacy

A cochlear implant will not cure deafness, but is a prosthetic substitute for hearing. Some recipients find them very effective, others somewhat effective and some feel worse overall with the implant than without.[64]

On the other hand, there are efficiency studies that show that unilateral implantation is highly cost efficient and that there is a decrease in the societal cost in comparison to non-implanted children.[65][66]

For people already functional in spoken language who lose their hearing, cochlear implants can be a great help in restoring functional comprehension of speech, especially if they have only lost their hearing for a short time.

Individuals who have acquired deafblindness (loss of hearing and vision combined) may find cochlear implants a radical improvement in their daily lives. It may provide them with more information for safety, communication, balance, orientation and mobility and promote interaction within their environment and with other people, reducing isolation. Having more auditory information than they may be familiar with may provide them with sensory information that will help them become more independent.

British Member of Parliament Jack Ashley received a cochlear implant in 1994 at age 70 after 25 years of deafness, and reported that he has no trouble speaking to people he knows; whether one on one or even on the telephone, although he might have difficulty with a new voice or with a busy conversation, and still had to rely to some extent on lip reading. He described the robotic sound of human voices perceived through the cochlear implant as "a croaking Dalek with laryngitis". Another recipient described the initial sounds as similar to radio static and voices as being cartoonish, though after a year with the implant she said everything sounded right.[67] Even modern cochlear implants have at most 22 electrodes to replace the 16,000 delicate hair cells that are used for normal hearing. However, the sound quality delivered by a cochlear implant is often good enough that many users do not have to rely on lip reading in quiet conditions. In noisy conditions however, speech understanding often remains poor.[68]

Adults who have grown up deaf can find the implants ineffective or irritating. This relates to the specific pathology of deafness and the time frame. Adults who are born with normal hearing and who have had normal hearing for their early years and who have then progressively lost their hearing tend to have better outcomes than adults who were born deaf. This is due to the neural patterns laid down in the early years of life, which are crucially important to speech perception. Cochlear implants cannot overcome such a problem. Some who were orally educated and used amplifying hearing aids have been more successful with cochlear implants, as the perception of sound was maintained through use of the hearing aid. Daily exercises such as side by side tracking, listening to audio books while reading a print book, synthetic training, and analytic training can improve the efficacy of an implant through practice.[69]

Children without a working auditory nerve may be helped with a cochlear implant, although the results may not be optimal. Patients without a viable auditory nerve are usually identified during the candidacy process. Fewer than 1% of deaf individuals have a missing or damaged auditory nerve, which today can be treated with an auditory brainstem implant. Research published in 2005 has suggested that children and adults can benefit from bilateral cochlear implants in order to aid in sound localization and speech understanding,[70] and a 2011 study indicated that the language skills of children with two implants were within the normal range for the age.[71]

Efficacy of cochlear implantation in the setting of otosclerosis has been demonstrated.[72]

Risks and disadvantages

Some effects of implantation are irreversible; while the device promises to provide new sound information for a recipient, the implantation process inevitably results in shaving of the hair cells within the cochlea,[73] which can result in a permanent loss of some or all residual natural hearing. However, with flexible electrodes and the right surgical methods, the hair cells can be preserved. While recent improvements in implant technology, and implantation techniques, promise to minimize such damage, the risk and extent of damage still varies. The goal of new implantation techniques is to reduce the risk of infection, operating time, and complications while improving the patient's ability to hear. Such improvements of implantation techniques include preserving low frequency hearing and using minimal invasive surgery to better secure the device.[74][75] Still, the cause of deafness is not always identified before the surgery. It is possible but rare that the surgery does not restore hearing at all.

The United States Food and Drug Administration reports that cochlear implant recipients may be at higher risk for meningitis.[76] A study of 4,265 American children who received implants between 1997 and 2002 concluded that recipient children had a risk of pneumococcal meningitis more than 30 times greater than that for children in the general population.[77] A later, UK-based, study found that while the incidence of meningitis in implanted adults was significantly higher than the general population, the incidence in children was no different from the general population.[78] As a result, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration both recommend that would-be implant recipients be vaccinated against meningitis prior to surgery.[79]

Rarely, necrosis has been observed in the skin flaps surrounding cochlear implants.[80][81] Hyperbaric oxygen has been shown to be a useful adjunctive therapy in the management of cochlear implant flap necrosis.[82]

As the location of the cochlea is close to the facial nerve, there is a risk that the nerve may be damaged during the operation. The incidence of the damage is infrequent.[83]

There are strict protocols in choosing candidates to avoid risks and disadvantages. A battery of tests is performed to make the decision of candidacy easier. For example, some patients suffer from deafness medial to the cochlea - typically vestibular schwannomas. Implantation into the cochlea has a low success rate with these people, as the artificial signal does not have a healthy nerve to travel along. Historically, patients with severe congenital anatomic anomalies of the cochlea were considered poor candidates for cochlear implantation. Many studies since the 1980s have demonstrated successful hearing outcomes after CI in this group. Blake Papsin et al. in 2005 published the largest series of patients with cochleovestibular anomalies undergoing implantation and found no significant difference in outcomes versus patients with normal anatomy.[84] Michael Pakdaman et al. in 2012 presented a systematic review of studies reviewing cochlear implantation in anomalous inner ears and found increased surgical difficulty and lower speech perception among patients with more severe inner ear dysplasia.[85] With careful selection of candidates, the risks of implantation are minimized.

Functionality

The implant works by using the tonotopic organization of the basilar membrane of the inner ear. "Tonotopic organization", also referred to as a "frequency-to-place" mapping, is the way the ear sorts out different frequencies so that our brain can process that information. In a normal ear, sound vibrations in the air lead to resonant vibrations of the basilar membrane inside the cochlea. High-frequency sounds (i.e. high pitched sounds) do not pass very far along the membrane, but low frequency sounds pass farther in. The movement of hair cells, located all along the basilar membrane, creates an electrical disturbance that can be picked up by the surrounding nerve cells. The brain is able to interpret the nerve activity to determine which area of the basilar membrane is resonating, and therefore what sound frequency is being heard.

In individuals with sensorineural hearing loss, hair cells are often fewer in number and/or damaged. Hair cell loss or absence may be caused by a genetic mutation or an illness such as meningitis. Hair cells may also be destroyed chemically by an ototoxic medication, or simply damaged over time by excessively loud noises. The cochlear implant bypasses the hair cells and stimulates the cochlear nerves directly using electrical impulses. This allows the brain to interpret the frequency of sound as it would if the hair cells of the basilar membrane were functioning properly (see above).

Processing

Sound received by the microphone must next be processed to determine how the electrodes should be activated.

Filterbank strategies use fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) to divide the signal into different frequency bands. The algorithm chooses a number of the strongest outputs from the filters, the exact number depending on the number of implanted electrodes and other factors. These strategies emphasize transmission of the spectral aspects of speech. Although coarse temporal information is presented, the fine timing aspects are as yet poorly perceived, and this is the focus of much current research.

Feature extraction strategies use features which are common to all vowels. Each vowel has a fundamental frequency (the lowest frequency peak) and formants (peaks with higher frequencies). The pattern of the fundamental and formant frequencies is specific for different vowel sounds. These algorithms try to recognize the vowel and then emphasize its features. These strategies emphasize the transmission of spectral aspects of speech. Feature extraction strategies are no longer widely used. Cochlear implant manufacturer use various coding strategies. Cochlear Americas, for example, uses the Speak-ACE strategy. ACE is mainly used, in which number of maxima (n) from the available maxima in sound are selected. Advanced Bionics uses other techniques like CIS, SAS, HiRes, and Fidelity 120, which stimulate the full spectrum. The processing strategy is a main block upon which one has to choose the implant manufacturer. Research shows that patients can understand speech with at least 4 electrodes, but a greater obstacle is in music perception, where it returns that fine structure stimulation is an important issue. Some strategies used in Advanced Bionics and Med-el devices make use of fine structure presentation by implementing the Hilbert transform in the signal processing path, while ACE strategies depends mainly on the short time Fourier transform.

Transmitter

This is used to transmit the processed sound information over a radio frequency link to the internal portion of the device. Radio frequency is used so that no physical connection is needed, which reduces the chance of infection and pain. The transmitter attaches to the receiver using a magnet that holds through the skin.

Receiver

This component receives directions from the speech processor by way of magnetic induction sent from the transmitter. (The receiver also receives its power through the transmission.) The receiver is also a sophisticated computer that translates the processed sound information and controls the electric current sent to the electrodes in the cochlea. It is embedded in the skull behind the ear.

Electrode array

The electrode array is made from a type of silicone rubber, while the electrodes are platinum or a similar highly conductive material. It is connected to the internal receiver on one end and inserted into the cochlea deeper in the skull. (The cochlea winds its way around the auditory nerve, which is tonotopically organized as is the basilar membrane). When an electric current is routed to an intracochlear electrode, an electrical field is generated and auditory nerve fibers are stimulated.

In the devices manufactured by Cochlear Ltd two electrodes sit outside the cochlea and act as grounds—one is a ball electrode that sits beneath the skin, while the other is a plate on the device. This equates to 24 electrodes in the Cochlear-brand 'nucleus' device: 22 array electrodes within the cochlea and 2 extra-cochlear electrodes.

Insertion depth is another important consideration. The mean length of the human cochlea is 33–36 millimetres (1.3–1.4 in), due to some physical limitation, the implants do not reach to the apical tip when inserted but it may reach up to 25 millimetres (0.98 in) which corresponds to a tonotopical frequency of 400–6000 Hz. Med-el produces long electrode arrays that can be inserted up to a tonotopical frequency of 100 Hz (according to Greenwood frequency to position formula in normal hearing), but the distance between the electrodes is about 2.5 millimetres (0.098 in), while in the Nucleus Freedom from Cochlear Ltd it is about 0.7 millimetres (0.028 in). There is strong research in this direction and the best sounding implant can be subjective from patient to patient.

Speech processors

Speech processors are the components of the cochlear implant that transforms the sounds picked up by the microphone into electronic signals capable of being transmitted to the internal receiver. The coding strategies programmed by the user's audiologist are stored in the processor, where it codes the sound accordingly. The signal produced by the speech processor is sent through the coil to the internal receiver, where it is picked up by radio signal and sent along the electrode array in the cochlea.

There are primarily two forms of speech processors available. The most common kind is called the "behind-the-ear" processor, or BTE. It is a small processor that is worn on the ear, typically together with the microphone. This is the kind of processor used by most adults and older children. Babies and small children wear either a "baby" BTE (pinned or clipped to the collar) or the body-worn processor, which was more common in previous years. Today's tiny processors can often take the place of bulky body-worn processors. Med-el and Cochlear brands both carry a "baby BTE" configurations. Med-el launched in 2013 the world’s first single unit processor, which is attached through magnet to the implant and leaves the ear completely free.

Programming the speech processor

The audiologist sets the minimum and maximum current level outputs for each electrode in the array based on the user's reports of loudness. The audiologist also selects the appropriate speech processing strategy and program parameters for the user.

Scientific and technical advances

Professor Graeme Clark A.C. of La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia, in 2008, announced the beginning of the development of a prototype "hi fi" cochlear implant featuring 50 electrodes. It is hoped that the increased number of electrodes will enable users to perceive music and discern specific voices in noisy rooms.[86]

Researchers at Northwestern University have used infrared lasers to directly stimulate the neurons in the inner ear of deaf guinea pigs while recording electrical activity in the inferior colliculus, an area of the midbrain that acts as a bridge between the inner ear and the auditory cortex. The laser stimulation produced more precise signals in that brain region than the electrical stimulation commonly used in cochlear implants.[87] Laser stimulation is a promising technology for improving the auditory resolution of implants but further research using fiber optics to stimulate the neurons of the inner ear is required before products using the technology can be developed.

Cochlear implants are rarely used in ears that have a functional level of residual hearing. However, Electric Acoustic Stimulation (EAS) devices, including the Hybrid "short-electrode" cochlear implant, have been developed that combine a cochlear implant with a sound amplifying hearing aid.[88][89] EAS devices have the potential to make cochlear implants suitable for many people with partial hearing loss. The sound amplifying component helps users to perceive lower frequency sounds through their residual natural hearing while the cochlear implant allows them to hear middle and higher frequency sounds. The combination enhances speech perception in noisy environments.[90]

Additionally, work is being done to develop a fully internal cochlear implant. As of April 2011, four people have undergone a trial of an internal microphone system, with two more yet to come.[91]

Manufacturers

Currently (as of 2013), the three cochlear implant devices approved for use in the U.S. are manufactured by Cochlear Limited (Australia), Advanced Bionics (USA, a division of Sonova) and MED-EL (Austria). In Europe, Africa, Asia, South America, and Canada, an additional device manufactured by Neurelec (France, a division of William Demant) is available. A device made by Nurotron (China) is also available in some parts of the world. Each manufacturer has adapted some of the successful innovations of the other companies to its own devices. There is no consensus that any one of these implants is superior to the others. Users of all devices report a wide range of performance after implantation.

Since the devices have a similar range of outcomes, other criteria are often considered when choosing a cochlear implant: FM system compatibility, usability of external components, cosmetic factors, battery life, reliability of the internal and external components, MRI compatibility, mapping strategies, customer service from the manufacturer, the familiarity of the user's surgeon and audiologist with the particular device, and anatomical concerns.

There have been reports of other organizations working to develop cochlear implants in India by a branch of the Defence Research and Development Organisation[92] (which is expected to reach the clinical trial stage around September 2012[93]) and in South Korea by the Seoul National University Hospital.[94]

Criticism and controversy

Much of the strongest objection to cochlear implants has come from the Deaf community, which consists largely of pre-lingually deaf people whose first language is a sign language. For some in the Deaf community, cochlear implants are an affront to their culture, which as they view it, is a minority threatened by the hearing majority.[95] This is an old problem for the deaf community, going back as far as the 18th century with the argument of manualism vs. oralism. This is consistent with medicalisation and the standardisation of the 'normal' body in the 19th century, when differences between normal and abnormal began to be debated.[96] Despite the cochlear implant being justified from a medical perspective, it is also important to consider the sociocultural context, particularly in regards to the Deaf community, which considers itself to possess its own unique language and culture.[97] This accounts for the cochlear implant being seen as an affront to their culture, as many do not believe that deafness is something that needs to be cured. However, it has also been argued that this does not necessarily have to be the case; the cochlear implant can act as a tool Deaf people can use to access the 'hearing world' without losing their Deaf identity.[97]

Cochlear implants for congenitally deaf children are considered to be most effective when implanted at a young age, during the critical period in which the brain is still learning to interpret sound.[50] Hence they are implanted before the recipients can decide for themselves, on the assumption that deafness is a disability. Deaf culture critics argue that the cochlear implant and the subsequent therapy often become the focus of the child's identity at the expense of a possible future deaf identity and ease of communication in sign language, and claim that measuring the child's success only by their mastery of hearing and speech will lead to a poor self-image as "disabled" (because the implants do not produce normal hearing) rather than having the healthy self-concept of a proudly deaf person.[98]

Children with cochlear implants are more likely to be educated orally, in the standard fashion, and without access to sign language (Spencer et al. 2003). They are often isolated from other deaf children and from sign language (Spencer 2003). Children do not always receive support in the educational system to fulfill their needs as they may require special education environments and Educational Assistants. According to Johnston (2004), cochlear implants have been one of the technological and social factors implicated in the decline of sign languages in the developed world. Some of the more extreme responses from Deaf activists have labeled the widespread implantation of children as "cultural genocide".[54] Andrew Solomon of the New York Times states that "Much National Association of the Deaf propaganda about the danger of implants is alarmist; some of it is positively inaccurate."[99]

As the trend for cochlear implants in children grows, deaf-community advocates have tried to counter the "either or" formulation of oralism vs manualism with a "both and" approach; some schools now are successfully integrating cochlear implants with sign language in their educational programs.

See also

- Auditory brainstem implant

- Bone-anchored hearing aid

- Bone conduction

- Brain implant

- EABR

- Ear trumpet

- Electric Acoustic Stimulation

- Electrophonic hearing

- Hearing Aid

- Neuroprosthetics

- Noise health effects

- Visual prosthesis

References

- ↑ NIH Publication No. 11-4798 (2013-11-01). "Cochlear Implants". National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

According to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), as of December 2012, approximately 324,200 people worldwide have received implants. In the United States, roughly 58,000 adults and 38,000 children have received a cochlear implant.

- ↑ http://www.bium.univ-paris5.fr/histmed/medica/orld.htm

- ↑ http://www.bium.univ-paris5.fr/histmed/medica/orlj.htm

- 1 2 Chouard CH, Josset P, Meyer B, Buche JF; Josset; Meyer; Buche (1983). "Effet de la stimulation électrique chronique du nerf auditif sur le développement des noyaux cochléaires du cobaye" [Effect of chronic electric stimulation of the auditory nerve on the development of the cochlear nuclei in guinea pigs] (PDF). Annales D'oto-laryngologie et De Chirurgie Cervico Faciale (in French) 100 (6): 417–22. PMID 6688708.

- ↑ Klinke R, Kral A, Heid S, Tillein J, Hartmann R (1999). "Recruitment of the auditory cortex in congenitally deaf cats by long-term cochlear electrostimulation". Science 285: 1729–1733. doi:10.1126/science.285.5434.1729. PMID 10481008.

- ↑ Kral A, Hartmann R, Tillein J, Heid S, Klinke R. (2002). "Hearing after Congenital Deafness: Central Auditory Plasticity and Sensory Deprivation". Cereb Cortex 12 (8): 797–807. doi:10.1093/cercor/12.8.797. PMID 12122028.

- ↑ Kral A, Sharma A. (2012). "Developmental neuroplasticity after cochlear implantation.". Trends Neurosci 35 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2011.09.004. PMC 3561718. PMID 22104561.

- ↑ H. Davis. « Excitation of audiory receptors » In Handbook of physiology, Section 1 – Neurophysiology vol.1 1968. Ifield, HW Makgrun and VE Hall Ed.

- ↑ Kiang NY, Moxon EC; Moxon (October 1972). "Physiological considerations in artificial stimulation of the inner ear". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 81 (5): 714–30. doi:10.1177/000348947208100513. PMID 4651114.

- ↑ Evans EF (1975). "The sharpening of cochlear frequency selectivity in the normal and abnormal cochlea". Audiology 14 (5–6): 419–42. doi:10.3109/00206097509071754. PMID 1156249.

- ↑ Djourno A, Eyries C; Eyries (August 1957). "[Auditory prosthesis by means of a distant electrical stimulation of the sensory nerve with the use of an indwelt coiling]". La Presse Médicale (in French) 65 (63): 1417. PMID 13484817.

- ↑ House WF, House HP, Urban J; House; Urban (1959). "Operating microscope observation viewer and motion picture camera". Transactions - American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology 63 (2): 228–9. PMID 13659554.

- ↑ Eshraghi AA, Nazarian R, Telischi FF, Rajguru SM, Truy E, Gupta C; Nazarian; Telischi; Rajguru; Truy; Gupta (November 2012). "The cochlear implant: historical aspects and future prospects". Anatomical Record 295 (11): 1967–80. doi:10.1002/ar.22580. PMID 23044644.

- ↑ House WF, Urban J; Urban (1973). "Long term results of electrode implantation and electronic stimulation of the cochlea in man". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 82 (4): 504–17. doi:10.1177/000348947308200408. PMID 4721186.

- ↑ Simmons FB (July 1966). "Electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve in man". Archives of Otolaryngology 84 (1): 2–54. doi:10.1001/archotol.1966.00760030004003. PMID 5936537.

- ↑ Merzenich MM, Brugge JF; Brugge (February 1973). "Representation of the cochlear partition of the superior temporal plane of the macaque monkey". Brain Research 50 (2): 275–96. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(73)90731-2. PMID 4196192.

- ↑ http://www.nature.com/focus/Lasker/2013/pdf/ES-Lasker13-Clark.pdf[]

- ↑ Sooy F. and Michelson R.P. : An electrical cochlear prosthesis for profound sensory deafness. Clinical results. X World Congress of O.R.L. , Venise, Mai 73, Excerpta Medica Edit., Amsterdam, no. 276, p. 1.

- ↑ Chouard CH, Cathala HP; Cathala (October 1969). "[Indications of nerve decompression in facial paralysis 'a frigore']". La Presse Médicale (in French) 77 (42): 1471–4. PMID 5390513.

- ↑ Chouard CH (1973). "[Surgical treatment of vertigo by vestibular neurectomy. Principle and technic]". Revue De Laryngologie - Otologie - Rhinologie (in French) 94 (1): 51–8. PMID 4729625.

- ↑ Chouard CH, Mac Leod P; Mac Leod (December 1973). "[Letter: Rehabilitation of total deafness. Trial of cochlear implantation with multiple electrodes]". La Nouvelle Presse Médicale (in French) 2 (44): 2958. PMID 4775181.

- ↑ Mac Leold P, Pialoux P, Chouard CH, Meyer B; Pialoux; Chouard; Meyer (1975). "[Physiological assessment of the rehabilitation of total deafness by the implantation of multiple intracochlear electrodes]". Annales D'oto-laryngologie et De Chirurgie Cervico Faciale (in French) 92 (1–2): 17–23. PMID 1217800.

- ↑ Tong YC, Black RC, Clark GM; et al. (July 1979). "A preliminary report on a multiple-channel cochlear implant operation". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology 93 (7): 679–95. doi:10.1017/S0022215100087545. PMID 469398.

- ↑ Chouard CH, Pialoux P, Mac Leod P, Charachon R, Meyer B , Soudant J., Morgon A. Stimulation électrique du nerf cochléaire chez l’homme. XII° Congrès International d’Audiologie, Paris 1974.

- ↑ Accoyer B, Charachon R, Richard J; Charachon; Richard (June 1974). "[Electrocochlearography. First clinical results]". JFORL. Journal Français D'oto-rhino-laryngologie (in French) 23 (6): 499–505. PMID 4280410.

- ↑ Accoyer B. Approche théorique et clinique du traitement des surdités totales par implantations chroniques d’électrodes intra-cochléaire multiples ; Thèse Médecine, Grenoble, janvier 1976, 184 pages.

- ↑ Burian K (June 1975). "[Letter: Significance of cochlear nerve electric stimulation in totally deaf patients]". Laryngologie, Rhinologie, Otologie (in German) 54 (6): 530–1. PMID 125832.

- ↑ Chouard CH, Mac Leod P, Meyer B, Pialoux P; Mac Leod; Meyer; Pialoux (1977). "[Surgically implanted electronic apparatus for the rehabilitation of total deafness and deaf-mutism]". Annales D'oto-laryngologie et De Chirurgie Cervico Faciale (in French) 94 (7–8): 353–63. PMID 606046.

- ↑ Pialoux P, Chouard CH, Meyer B, Fugain C; Chouard; Meyer; Fugain (1979). "Indications and results of the multichannel cochlear implant". Acta Oto-laryngologica 87 (3–4): 185–9. doi:10.3109/00016487909126405. PMID 442998.

- 1 2 "The importance of being flexible" (PDF). Laske Foundation.

- ↑ Hochmair ES, Hochmair-Desoyer IJ, Burian K; Hochmair-Desoyer; Burian (September 1979). "Investigations towards an artificial cochlea". The International Journal of Artificial Organs 2 (5): 255–61. PMID 582589.

- ↑ http://www.laskerfoundation.org/awards/2013_c_accept_clark.htm[]

- ↑ Eyries C, Chouard CH; Chouard (June 1970). "[Acoustico-facial anastomoses]". Annales D'oto-laryngologie et De Chirurgie Cervico Faciale (in French) 87 (6): 321–6. PMID 5424456.

- ↑ MINIMAC: a totally numeric 15 channel implanted stimulator. Chouard CH, Weber JL. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1989 Apr;12(4 Pt 2):743-8

- ↑ Tye-Murray N, Lowder M, Tyler RS; Lowder; Tyler (June 1990). "Comparison of the F0F2 and F0F1F2 processing strategies for the Cochlear Corporation cochlear implant". Ear and Hearing 11 (3): 195–200. doi:10.1097/00003446-199006000-00005. PMID 2358129.

- 1 2 "The importance of being flexible" (PDF). Lasker Foundation.

- ↑ Chouard CH, Meyer B, Fugain C, Koca O; Meyer; Fugain; Koca (May 1995). "Clinical results for the DIGISONIC multichannel cochlear implant". The Laryngoscope 105 (5 Pt 1): 505–9. doi:10.1288/00005537-199505000-00011. PMID 7760667.

- ↑ Uziel AS, Reuillard-Artières F, Mondain M, Piron JP, Sillon M, Vieu A; Reuillard-Artières; Mondain; Piron; Sillon; Vieu (1993). "Multichannel cochlear implantation in prelingually and postlingually deaf children". Advances in Oto-rhino-laryngology 48: 187–90. PMID 8273477.

- ↑ Uziel AS, Reuillard-Artieres F, Sillon M; et al. (1995). "Speech perception performance in prelingually deafened children with the nucleus multichannel cochlear implant". Advances in Oto-rhino-laryngology 50: 114–8. PMID 7610945.

- ↑ http://recorlsa.online.fr/implantcochleaire/historicfrancaisenanglais.html#frenchpatents

- 1 2 "World's First". Med-el.

- ↑ abstracts book of 3rd International Congress on Cochlear Implants (Paris, 27–29 April 1995), Paris, France

- ↑ "Technical survey of the French role in multichannel cochlear implant development.". Acta Otolaryngol: 1–9. Dec 2014. doi:10.3109/00016489.2014.968804. PMID 25496058.

- ↑ "The early days of the multi channel cochlear implant: Efforts and achievement in France.". Hear Res 322: 47–51. Dec 2014. doi:10.1016/j.heares.2014.11.007. PMID 25499127.

- ↑ Avis no. 103. Éthique et surdité de l’enfant : éléments de réflexions à propos de l’information sur le dépistage précoce de la surdité dans les maternités

- ↑ http://www2.biusante.parisdescartes.fr/wordpress/index.php/tricentenaire-abbe-epee

- ↑ L’enfant sourd profond. Morgon A. Bull. Acad. Natle Méd., 2006, 190, no 8, 1653-1662

- ↑ Shapiro, Joseph (2005-12-20). "Elderly with Hearing Loss Turning to Cochlear Implants". Day to Day (National Public Radio). Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ↑ Kral A, O'Donoghue GM; O'Donoghue (October 2010). "Profound deafness in childhood". The New England Journal of Medicine 363 (15): 1438–50. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0911225. PMID 20925546.

- 1 2 Paul Oginni (2009-11-16). "UCI Research with Cochlear Implants No Longer Falling on Deaf Ears". New University. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ↑ Kral A, Hubka P, Heid S, Tillein J; Hubka; Heid; Tillein (January 2013). "Single-sided deafness leads to unilateral aural preference within an early sensitive period". Brain 136 (Pt 1): 180–93. doi:10.1093/brain/aws305. PMID 23233722.

- ↑ Gordon KA, Wong DD, Papsin BC; Wong; Papsin (May 2013). "Bilateral input protects the cortex from unilaterally-driven reorganization in children who are deaf". Brain 136 (Pt 5): 1609–25. doi:10.1093/brain/awt052. PMID 23576127.

- ↑ van der Heijden, Dennis (2006-03-01). "What are Cochlear Implants?". Axistive. Retrieved 2007-03-01.

- 1 2 Amy E. Nevala (2000-09-28). "Not everyone is sold on the cochlear implant". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ "Cochlear Corp. News".

- ↑ "Cochlear Corp. News".

- ↑ Priyanka Golikeri (2010-07-14). "Costly cochlear implants beyond reach of masses". dnaindia.com. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ Hamerschmidt R, Moreira AT, Wiemes GR, Tenório SB, Tâmbara EM; Moreira; Wiemes; Tenório; Tâmbara (January 2013). "Cochlear implant surgery with local anesthesia and sedation: comparison with general anesthesia". Otology & Neurotology 34 (1): 75–8. doi:10.1097/MAO.0b013e318278c1b2. PMID 23187931.

- ↑ "In Sync with Natural Hearing". Audiology Worldnews.

- ↑ Dotinga, Randy (2006-08-06). "Slides: a playground menace". Wired. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ↑ Solomon, Andrew (1994-08-28). "Defiantly deaf". New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ↑ http://beaumont.ie/index.jsp?p=350&n=407&a=0

- ↑ John M. Williams (2000-05-05). "Do Health-Care Providers Have to Pay for Assistive Tech?". Business Week. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ↑ Delost, Shelli; Sarah Lashley (2000–03). "Drury Interdisciplinary Research Conference". Check date values in:

|date=(help);|contribution=ignored (help) - ↑ Summerfield AQ1, Marshall DH, Archbold S. (1997). "Cost-effectiveness considerations in pediatric cochlear implantation". Am J Otol 18 (6 Suppl): 166–8.

- ↑ Colletti L1, Mandalà M, Shannon RV, Colletti V.; Mandalà; Shannon; Colletti (2011). "Estimated net saving to society from cochlear implantation in infants: a preliminary analysis". Laryngoscope 121 (11): 2455–60. doi:10.1002/lary.22131. PMID 22020896.

- ↑ Rempp, Kerri (2009-06-11). "City clerk outsmarts heredity". The Chaldron Record. Retrieved 2009-06-19.

- ↑ Erin C. Schafer, Linda M. Thibodeau; Thibodeau (2004). "Speech recognition abilities of adults using CIs interfaced with FM systems". Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 15 (10): 678–691. doi:10.3766/jaaa.15.10.3. PMID 15646666.

- ↑ Tools for Improving Listening Skills, Hope: Cochlear (Re) Habilitation Resources, http://hope.cochlearamericas.com/Tools-for-Improving-Listening-Skills

- ↑ Offeciers E, Morera C, Müller J, Huarte A, Shallop J, Cavallé L.; Morera; Müller; Huarte; Shallop; Cavallé (Sep 2005). "International consensus on bilateral cochlear implants and bimodal stimulation". Acta Otolaryngol. 125 (9): 918–919. doi:10.1080/00016480510044412. PMID 16109670.

- ↑ Tenenbaum, David (2011-10-24). "Deaf children: Study shows significant language progress after two cochlear implants (Oct. 24, 2011)". news.wisc.edu. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ↑ Marshall AH, Fanning N, Symons S, Shipp D, Chen JM, Nedzelski JM (October 2005). "Cochlear implantation in cochlear otosclerosis". Laryngoscope 115 (10): 1728–1733. doi:10.1097/01.mlg.0000171052.34196.ef.

- ↑ http://www.surgeryencyclopedia.com/Ce-Fi/Cochlear-Implants.html[]

- ↑ Gstoettner W, Kiefer J, Baumgartner WD, Pok S, Peters S, Adunka O; Kiefer; Baumgartner; Pok; Peters; Adunka (May 2004). "Hearing preservation in cochlear implantation for electric acoustic stimulation". Acta Oto-laryngologica 124 (4): 348–52. doi:10.1080/00016480410016432. PMID 15224851.

- ↑ Monksfield P, Husseman J, Cowan RS, O'Leary SJ, Briggs RJ; Husseman; Cowan; O'Leary; Briggs (August 2012). "The new Nucleus 5 model cochlear implant: a new surgical technique and early clinical results". Cochlear Implants International 13 (3): 142–7. doi:10.1179/1754762811Y.0000000012. PMID 22333886.

- ↑ "FDA Public Health Notification: Risk of Bacterial Meningitis in Children with Cochlear Implants". FDA. July 24, 2002. Archived from the original on 2008-09-25. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ Biernath KR, Reefhuis J, Whitney CG; et al. (February 2006). "Bacterial meningitis among children with cochlear implants beyond 24 months after implantation". Pediatrics 117 (2): 284–9. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0824. PMID 16390918.

- ↑ Summerfield AQ, Cirstea SE, Roberts KL, Barton GR, Graham JM, O'Donoghue GM; Cirstea; Roberts; Barton; Graham; O'Donoghue (March 2005). "Incidence of meningitis and of death from all causes among users of cochlear implants in the United Kingdom". Journal of Public Health 27 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdh188. PMID 15564280.

- ↑ "Maryland Hearing and Balance Center". University of Maryland Medical Center. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- ↑ Haberkamp TJ, Schwaber MK; Schwaber (January 1992). "Management of flap necrosis in cochlear implantation". Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 101 (1): 38–41. doi:10.1177/000348949210100111. PMID 1728883.

- ↑ Stratigouleas ED, Perry BP, King SM, Syms CA; Perry; King; Syms Ca (September 2006). "Complication rate of minimally invasive cochlear implantation". Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 135 (3): 383–6. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2006.03.023. PMID 16949968. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ↑ Schweitzer VG, Burtka MJ (1990). "Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy in the Management of Cochlear Implant Flap Necrosis.". J. Hyperbaric Med 5 (2): 81–90. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ↑ Patricia M. Chute; Mary Ellen Nevins (2002). The Parents' Guide to Cochlear Implants. Gallaudet University Press. p. 44. ISBN 1-56368-129-3.

- ↑ Papsin, BC (January 2005). "Cochlear implantation in children with anomalous cochleovestibular anatomy.". The Laryngoscope 115 (1 Pt 2 Suppl 106): 1–26. doi:10.1097/00005537-200501001-00001. PMID 15626926.

- ↑ Pakdaman, MN; Herrmann, BS, Curtin, HD, Van Beek-King, J, Lee, DJ; Curtin, H. D.; Van Beek-King, J; Lee, D. J. (Dec 1, 2011). "Cochlear Implantation in Children with Anomalous Cochleovestibular Anatomy: A Systematic Review". Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 146 (2): 180–90. doi:10.1177/0194599811429244. PMID 22140206.

- ↑ Cochlear implant maker says hi-fi bionic ear will help the deaf hear music. News.com.au, December 18, 2008.

- ↑ Nowak, R. (2008). Light opens up a world of sound for the deaf. New Scientist.

- ↑ UT Southwestern Medical Center (2008, April 28). New Hybrid Hearing Device Combining Advantages Of Hearing Aids, Implants. ScienceDaily. Retrieved December 22, 2008, from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/04/080417100013.htm

- ↑ Gantz, B.G. and Turner, C.W. (2004) Combining acoustic and electrical speech processing: Iowa/Nucleus hybrid implant. Acta Otolaryngol 124: 344-347. See also: http://www.nationalreviewofmedicine.com/issue/2006/03_30/3_advances_medicine02_6.html

- ↑ Turner, C.W., Gantz, B.J., Vidal, C., et al. (2004) Speech recognition in noise for cochlear implant listeners: Benefits of residual acoustic hearing J. Acoust. Soc. Am. Volume 115, Issue 4, pp. 1729-1735.

- ↑ Graham-Rowe, Duncan (2011-04-04). "Ear implants for the deaf with no strings attached - tech - 04 April 2011 - New Scientist". newscientist.com. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- ↑ "Cheaper, lighter biomedical equipment using Def-tech". Zee News. 2010-03-05. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ "Defence Research and Development Organisation develops affordable cochlea implant". indiatimes.com. 2012-05-20. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- ↑ Bae Ji-sook (2010-02-28). "Procedure Gives Hearing to Auditory Disabled". The Korea Times. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ "The Cochlear Implant Controversy, Issues And Debates". NEW YORK: CBS News. September 4, 2001. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ Lock, M. and Nguyen, V-K., An Anthropology of Biomedicine, Oxford, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

- 1 2 Power D (2005). "Models of deafness: cochlear implants in the Australian daily press". Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 10 (4): 451–9. doi:10.1093/deafed/eni042. PMID 16000690.

- ↑ NAD Cochlear Implant Committee. "Cochlear Implants". Archived from the original on 2007-02-20.

- ↑ Solomon, Andrew (1994-08-28). "Defiantly deaf". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-30.

Further reading

- A wide range of information and activities designed to help recipients and the professionals they work with develop or re-learn listening and language skills - http://www.cochlear.com/wps/wcm/connect/in/home/connect/rehabilitation-resources/rehabilitation-resources

- Berruecos, Pedro. (2000). Cochlear implants: An international perspective - Latin American countries and Spain. Audiology. Hamilton: Jul/Aug 2000. Vol. 39, 4:221-225

- House, W. F., Cochlear Implants. Ann Otol Rhinol Larynogol 1976; 85 (suppl 27): 1 – 93.

- Simmons, F. B., Electrical Stimulation of the Auditory Nerve in Man, Arch Otolaryng, Vol 84, July 1966

- Pialoux, P., Chouard, C. H. and MacLeod, P. 1976. Physiological and clinical aspects of the rehabilitation of total deafness by implantation of multiple intracochlear electrodes. Acta Oto-Laryngologica 81: 436-441

- Chorost, Michael. (2005). Rebuilt: How Becoming Part Computer Made Me More Human. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Christiansen, John B. (2010) Reflections: My Life in the Deaf and Hearing Worlds. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Christiansen, John B., and Irene W. Leigh (2002,2005). Cochlear Implants in Children: Ethics and Choices. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Cooper, Huw R. and Craddock, Louise C. (2006)Cochlear Implants A Practical Guide. London and Philadelphia: Whurr Publishers.

- Djourno A, Eyriès C (1957). "Prothèse auditive par excitation électrique à distance du nerf sensoriel à l'aide d'un bobinage inclus à demeure.". La Presse Médicale 65 (63).

- Djourno A, Eyriès C, (1957) 'Vallencien B. De l'excitation électrique du nerf cochléaire chez l'homme, par induction à distance, à l'aide d'un micro-bobinage inclus à demeure.' CR de la société.de biologie. 423-4. March 9, 1957.

- Eisen MD (May 2003). "Djourno, Eyries, and the first implanted electrical neural stimulator to restore hearing.". Otology and Neurotology 24 (3): 500–6. doi:10.1097/00129492-200305000-00025.

- Grodin, M. (1997). Ethical Issues in Cochlear Implant Surgery: An Exploration into Disease, Disability, and the Best Interests of the Child. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 7:231-251.

- Johnston, Trevor. (2004). W(h)ither the deaf Community? In 'American Annals of the deaf' (volume 148 no. 5),

- Kral A, Sharma A (2012). "Developmental Neuroplasticity after Cochlear Implantation". Trends Neurosci 35 (2): 111–122. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2011.09.004. PMC 3561718. PMID 22104561.

- Kral A, Eggermont JJ (2007): What's to lose and what's to learn: Development under auditory deprivation, cochlear implants and limits of cortical plasticity. Brain Res Rev 56: 259-269.

- Lane, H. and Bahan, B. (1998). Effects of Cochlear Implantation in Young Children: A Review and a Reply from a DEAF-WORLD Perspective. Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery 119:297-308.

- Lane, Harlan (1993), Cochlear Implants:Their Cultural and Historical Meaning. In 'deaf History Unveiled', ed. J.Van Cleve, 272-291. Washington, D.C. Gallaudet University Press.

- Lane, Harlan (1994), The Cochlear Implant Controversy. World Federation of the deaf News 2 (3):22-28.

- Litovsky, Ruth Y., et al. (2006). "Bilateral Cochlear Implants in Children: Localization Acuity Measured with Minimum Audible Angle." Ear & Hearing, 2006; 27; 43-59.

- Miyamoto, R.T.,K.I.Kirk, S.L.Todd, A.M.Robbins, and M.J.Osberger. (1995). Speech Perception Skills of Children with Multichannel Cochlear Implants or Hearing Aids. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 105 (Suppl.):334-337

- Officiers, P.E., et. a. (2005). "International Consensus on bilateral cochlear implants and bimodal stimulation." Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 2005; 125; 918-919.

- Osberger M.J. and Kessler, D. (1995). Issues in Protocol Design for Cochlear Implant Trials in Children: The Clarion Pediatric Study. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology 9 (Suppl.):337-339.

- Reefhuis J; et al. (2003). "Risk of Bacterial Meningitis in Children with Cochlear Implants, USA 1997-2002". New England Journal of Medicine 349 (5): 435–445. doi:10.1056/nejmoa031101.

- Spencer, Patricia Elizabeth and Marc Marschark. (2003). Cochlear Implants: Issues and Implications. In 'Oxford Handbook of deaf Studies, Language and Education', ed. Marc Marschark and Patricia Elizabeth Spencer, 434-450. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- 3M Power Point Presentation on the Cochlear Implant.

- Barton G. Kids Hear Now Cochlear Implant Family Resource Center, University of Miami School of Medicine

External links

- Cochlear Implants at DMOZ

- What is it like to live with a cochlear implant? A short documentary video clip

- What do cochlear implants sound like? An audio example

- Cochlear Implants Information from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

- NASA Spinoff article on engineer Adam Kissiah's contribution to cochlear implants beginning in the 1970s.

- Wilson, Blake S.; Finley, Charles C.; Lawson, Dewey T.; Wolford, Robert D.; Eddington, Donald K.; Rabinowitz, William M. (1991). "Better speech recognition with cochlear implants". Nature 352 (6332): 236–8. Bibcode:1991Natur.352..236W. doi:10.1038/352236a0. PMID 1857418.

- NPR Story about improvements to improve the processing of music. Includes simulations of what someone with implants might hear.

- More recent NPR Story about improvements to improve the processing of music. Includes updated simulations of music, before and after these updates.

- Tuning In PBS article about advances in cochlear implant technology with simulations of what someone with each type of implant would hear.

- My Bionic Quest for Boléro (Wired, November 2005): Author Michael Chorost writes about his own implant and trying the latest software from researchers in a quest to hear music better.

- Charles Limb, "Building the musical muscle", TEDMED 2011, October 2011

|