Cloaca Maxima

The Cloaca Maxima (also called the Maxima Cloaca) is one of the world's earliest sewage systems. Constructed in Ancient Rome in order to drain local marshes and remove the waste of one of the world's most populous cities, it carried effluent to the River Tiber, which ran beside the city.[1]

Construction

The name literally means Greatest Sewer. According to tradition it may have been initially constructed around 600 BC under the orders of the king of Rome, Tarquinius Priscus.[2]

The Cloaca Maxima originally was built by the Etruscans as an open-air canal. Over time, the Romans covered over the canal and turned it into a sewer system for the city.[3]

This public work was largely achieved through the use of Etruscan engineers and large amounts of semi-forced labour from the poorer classes of Roman citizens. Underground work is said to have been carried out on the sewer by Tarquinius Superbus, Rome's seventh and last king.[4]

Although Livy describes it as being tunnelled out beneath Rome, he was writing centuries after the event. From other writings and from the path that it takes, it seems more likely that it was originally an open drain, formed from streams from three of the neighbouring hills, that were channelled through the main Forum and then on to the Tiber.[2] This open drain would then have been gradually built over, as building space within the city became more valuable. It is possible that both theories are correct, and certainly some of the main lower parts of the system suggest that they would have been below ground level even at the time of the supposed construction.

The eleven aqueducts which supplied water to Rome by the 1st century AD were finally channelled into the sewers after having supplied the many public baths such as the Baths of Diocletian and the Baths of Trajan, the public fountains, imperial palaces and private houses.[5][6] The continuous supply of running water helped to remove wastes and keep the sewers clear of obstructions. The best waters were reserved for potable drinking supplies, and the second quality waters would be used by the baths, the outfalls of which connected to the sewer network under the streets of the city. The aqueduct system was investigated by the general Frontinus at the end of the 1st century AD, who published his report on its state directly to the emperor Nerva.

Distribution system

The extraordinary greatness of the Roman Empire manifests itself above all in three things: the aqueducts, the paved roads, and the construction of the drains.

There were many branches off of the main sewer, but all seem to be 'official' drains that would have served public toilets, bath-houses and other public buildings. Private residences in Rome, even of the rich, would have relied on some sort of cess-pit arrangement for sewage.

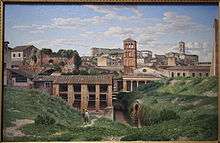

The Cloaca Maxima was well maintained throughout the life of the Roman Empire and even today drains rainwater and debris from the center of town, below the ancient Forum, Velabro and Foro Boario. In 33 BC it is known to have received an inspection and overhaul from Agrippa, and archaeology reveals several building styles and material from various ages, suggesting that the systems received regular attention. In more recent times, the remaining passages have been connected to the modern-day sewage system, mainly to cope with problems of backwash from the river.

The Cloaca Maxima was thought to be presided over by the goddess Cloacina.

The Romans are recorded – the veracity of the accounts depending on the case – to have dragged the bodies of a number of people to the sewers rather than give them proper burial, among them the emperor Elagabalus[8] [9] and Saint Sebastian: the latter scene is the subject of a well-known artwork by Lodovico Carracci.

The outfall of the Cloaca Maxima into the River Tiber is still visible today near the bridge Ponte Rotto, and near Ponte Palatino. There is a stairway going down to it visible next to the Basilica Julia at the Forum. Some of it is also visible from the surface opposite the church of San Giorgio al Velabro.

The Cloaca Maxima also helped stopping the spread of malaria in Rome. Every year the Tiber River flooded Rome. The water left over created marshes that made parts of the city unusable. The water attracted mosquitoes that spread malaria. The Cloaca Maxima helped to drain these marshes and get rid of the mosquitoes. The Romans did not know that mosquitoes carried the disease, but they figured out that they were getting sick because of the water. The drains still did not eliminate the disease. There was always water in the streets from overflowing fountains and the government washed trash out of the streets also leaving water. With so much standing water, it was impossible to get rid of the disease.[10]

The Empire

The system of Roman sewers was much imitated throughout the Roman Empire, especially when combined with copious supplies of water from Roman aqueducts. The sewer system in Eboracum—the modern-day English city of York—was especially impressive and part of it still survives.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ Aldrete, Gregory S. (2004). Daily life in the Roman city: Rome, Pompeii and Ostia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33174-9, pp.34-35.

- 1 2 Waters of Rome Journal - 4 - Hopkins.indd

- ↑ Hopkins, John N. N. "The Cloaca Maxima and the Monumental Manipulation of water in Archaic Rome". Institute of the Advanced Technology in the Humanities. Web. 4/8/12

- ↑ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1.56

- ↑ Woods, Michael (2000). Ancient medicine: from sorcery to surgery. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-2992-7, p.81.

- ↑ Lançon, Bertrand (2000). Rome in late antiquity: everyday life and urban change, AD 312-609. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92975-2, p.13.

- ↑ Quilici, Lorenzo (2008): "Land Transport, Part 1: Roads and Bridges", in: Oleson, John Peter (ed.): The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-19-518731-1, pp. 551–579 (552)

- ↑ Herodian, Roman History, 5.8.9

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/0/20627618

- ↑ Sura, Amol. "The Cloaca Maxima: Draining Disease from Rome." Classical Studies. Duke University, Spring 2010. Web. 26 Nov. 2013. <http://classicalstudies.duke.edu/uploads/assets/08_CloacaMaxima.pdf>.

- ↑ Darvill, Timothy, Stamper, Paul and Timby, Jane (2002). England: an Oxford archaeological guide to sites from earliest times to AD 1600. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284101-8, pp. 162-163.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cloaca Maxima. |

- Cloaca Maxima: article in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

- Pictures taken from inside the Cloaca Maxima

- Aquae Urbis Romae: The Waters of the City of Rome, Katherine W. Rinne

- The Waters of Rome: "The Cloaca Maxima and the Monumental Manipulation of Water in Archaic Rome" by John N. N. Hopkins

- Rome: Cloaca Maxima

Coordinates: 41°53′45″N 12°29′05″E / 41.8957°N 12.4848°E