Cleidocranial dysostosis

| Cleidocranial dysostosis | |

|---|---|

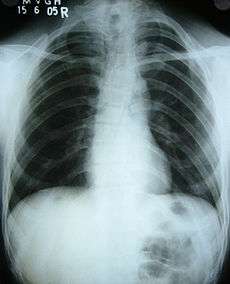

Hypoplasia of the clavicles and bell-shaped rib cage in the patient with CDD | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | medical genetics |

| ICD-10 | Q74.0 |

| ICD-9-CM | 755.59 |

| OMIM | 119600 |

| DiseasesDB | 30594 |

| MedlinePlus | 001589 |

| MeSH | D002973 |

| GeneReviews | |

Cleidocranial dysostosis, also called cleidocranial dysplasia or mutational dysostosis, is a hereditary congenital disorder, where there is delayed ossification of midline structures.

Etiopathogenesis

It is usually autosomal dominant, but in some cases the cause is not known.[1] It occurs due to haploinsufficiency caused by mutations in the CBFA1 gene (also called Runx2), located on the short arm of chromosome 6, which encodes transcription factor required for osteoblast differentiation.[2] It results in delayed ossification of midline structures of the body, particularly membranous bone.

A new article reports that the CCD aetiology is thought to be due to a CBFA1 (core binding factor activity 1) gene defect on the short arm of chromosome 6p21 . CBFA1 is vital for differentiation of stem cells into osteoblasts , so any defect in this gene will cause defects in membranous and endochondral bone formation.[3]

Clinical features

Cleidocranial dysostosis is a general skeletal condition[4] so named from the collarbone (cleido-) and cranium deformities which people with it often have.

People with the condition usually present with a painless swelling in the area of the clavicles at 2–3 years of age.[5] Common features are:

- Clavicles (collarbones) can be partly missing leaving only the medial part of the bone. In 10% cases, they are completely missing.[2] If the collarbones are completely missing or reduced to small vestiges, this allows hypermobility of the shoulders including ability to touch the shoulders together in front of the chest.[6] The defect is bilateral 80% of the time.[7] Partial collarbones may cause nerve damage symptoms and therefore have to be removed by surgery.

- The mandible is prognathic due to hypoplasia of maxilla (micrognathism) and other facial bones.[6]

- A soft spot or larger soft area in the top of the head where the fontanelle failed to close, or the fontanelle closes late.

- Bones and joints are underdeveloped. People are shorter and their frames are smaller than their siblings who do not have the condition.

Panoramic view of the jaws showing multiple unerupted supernumerary teeth mimicking premolar, missing gonial angles and underdeveloped maxillary sinuses in cleidocranial dysplasia.

Panoramic view of the jaws showing multiple unerupted supernumerary teeth mimicking premolar, missing gonial angles and underdeveloped maxillary sinuses in cleidocranial dysplasia. - The permanent teeth include supernumerary teeth. Unless these supernumeraries are removed they will crowd the adult teeth in what already may be an underdeveloped jaw. If so, the supernumeraries will probably need to be removed to make space for the adult teeth. Up to 13 supernumarary teeth have been observed. Teeth may also be displaced. Cementum formation may be deficient.[8]

- Failure of eruption of permanent teeth.

- Bossing (bulging) of the forehead.

- Open skull sutures, large fontanelles.

- Hypertelorism.

- Delayed ossification of bones forming symphysis pubis, producing a widened symphysis.

- Coxa vara can occur, limiting abduction and causing Trendelenburg gait.

- Short medial fifth phalanges,[9] sometimes causing short and wide fingers.[10]

- Vertebral abnormalities.[9]

- On rare occasions, brachial plexus irritation can occur.[2]

- Scoliosis, spina bifida and syringomyelia have also been described.[2]

Other features are: parietal bossing, basilar invagination (atlantoaxial impaction), persistent metopic suture, abnormal ear structures with hearing loss, supernumerary ribs, hemivertebrae with spondylosis ,small and high scapulae, hypoplasia of iliac bones, absence of the pubic bone, short / absent fibular bones, short / absent radial bones, hypoplastic terminal phalanges.[11]

Diagnosis

Clinically, different features of the dysostosis are significant. Radiological imaging helps confirm the diagnosis. During gestation (pregnancy), clavicular size can be calculated using available nomograms. Wormian bones can sometimes be observed in the skull.[12]

Treatment

Around 5 years of age, surgical correction may be necessary to prevent any worsening of the deformity.[5] If the mother has dysplasia, caesarian delivery is necessary. Craniofacial surgery may be necessary to correct skull defects [12] Coxa vara is treated by corrective femoral osteotomies. If there is brachial plexus irritation with pain and numbness, excision of the clavicular fragments can be performed to decompress it.[2] In case of open fontanelle, appropriate headgear may be advised by the orthopedist for protection from injury.

Epidemiology

The incidence is estimated at 1:200,000.[12]

Notable cases

The comedian Emmett Furrow has no collarbones and uses the resulting extra shoulder mobility in comedy routines.

At the rescue of Jessica McClure, Ron Short, a muscular man (a roofing contractor) who was born without collarbones because of cleidocranial dysostosis and so could collapse his shoulders to work in cramped corners, arrived at the site and offered to go down the shaft; they accepted his offer, although did not use it.[13][14]

References

- ↑ Tanaka JL, Ono E, Filho EM, Castilho JC, Moraes LC, Moraes ME (September 2006). "Cleidocranial dysplasia: importance of radiographic images in diagnosis of the condition". J Oral Sci 48 (3): 161–6. doi:10.2334/josnusd.48.161. PMID 17023750.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Turek's Orthopaedics: Principles And Their Application. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005. pp. 251–252. ISBN 9780781742986.

- ↑ Saraswathivilasam S. Suresh, A Family With Cleidocranial Dysplasia And Crossed Ectopic Kidney In One Child, Acta Orthop. Belg. 2009, N° 4 (Vol. 75/4) p.521-527. http://www.actaorthopaedica.be/acta/article.asp?lang=en&navid=244&id=14667&mod=Acta

- ↑ Garg RK, Agrawal P (2008). "Clinical spectrum of cleidocranial dysplasia: a case report". Cases J 1 (1): 377. doi:10.1186/1757-1626-1-377. PMC 2614945. PMID 19063717.

- 1 2 Hefti, Fritz (2007). Pediatric Orthopedics in Practice. Springer. p. 478. ISBN 9783540699644.

- 1 2 Juhl, John (1998). Paul and Juhl's essentials of radiologic imaging, 7th ed. Lippincott-Raven. ISBN 9780397584215.

- ↑ Greene, Walter (2006). Netter's Orthopaedics, 1st ed. Masson. ISBN 9781929007028.

- ↑ Textbook of Radiology and Imaging: Volume 2, 7e. Elsevier Science Health Science Division. 2003. p. 1539. ISBN 9780443071096.

- 1 2 Vanderwerf, Sally (1998). Elsevier's medical terminology for the practicing nurse. Elsevier. p. 65. ISBN 9780444824707.

- ↑ Menkes, John (2006). Child Neurology, 7e. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 307. ISBN 9780781751049.

- ↑ http://radiopaedia.org/articles/cleidocranial-dysostosis

- 1 2 3 Lovell, Wood (2006). Lovell & Winter's Pediatric Orthopaedics, 6e. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 240. ISBN 9780781753586.

- ↑ Kennedy, J. Michael (1987-10-17). "Jessica Makes It to Safety—After 58 1/2 Hours". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Cleidocranial Dysplasia-An Enigma Among Anomalies

External links

- http://www.rarediseases.org/rare-disease-information/rare-diseases/byID/961/viewAbstract

- http://www.cafamily.org.uk/Direct/c37.html

- The National Craniofacial Association

- http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=6549

- http://www.dental.mu.edu/oralpath/lesions/cleidocraniadys/cleidocraniadys.htm

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?indexed=google&rid=gene.chapter.ccd

- Medical Imaging on CCD

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Cleidocranial Dysplasia

- Radiology of CCD Images from MedPix

- YouTube video of Shoulder Dance by comedian Emmet Furrow

- YouTube video of male teenager with no collarbones and thus hypermobile shoulders

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||