Clebsch–Gordan coefficients for SU(3)

In mathematical physics, Clebsch–Gordan coefficients are the expansion coefficients of total angular momentum eigenstates in an uncoupled tensor product basis. Mathematically, they specify the decomposition of the tensor product of two irreducible representations into a direct sum of irreducible representations, where the type and the multiplicities of these irreducible representations are known abstractly. The name derives from the German mathematicians Alfred Clebsch (1833–1872) and Paul Gordan (1837–1912), who encountered an equivalent problem in invariant theory.

Generalization to SU(3) of Clebsch–Gordan coefficients is useful because of their utility in characterizing hadronic decays, where a flavor-SU(3) symmetry exists (the Eightfold Way (physics)) that connects the three light quarks: up, down, and strange.

Groups

A group is a mathematical structure (usually denoted in the form  consisting of a set

consisting of a set  and a binary operation (*) (often called a 'multiplication'), satisfying the following properties:

and a binary operation (*) (often called a 'multiplication'), satisfying the following properties:

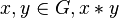

- Closure: For every pair of elements

and

and  in

in  , the product

, the product  is also in

is also in  ( in symbols, for every two elements

( in symbols, for every two elements  is also in

is also in

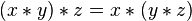

- Associativity: For every

and

and  and

and  in

in  , both

, both  and

and  result with the same element in

result with the same element in  ( in symbols,

( in symbols,  for every

for every  , and

, and  ).

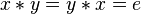

). - Existence of identity: There must be an element ( say

) in

) in  such that product any element of

such that product any element of  with

with  make no change to the element ( in symbols,

make no change to the element ( in symbols,  for every

for every  ).

). - Existence of inverse: For each element (

) in

) in  , there must be an element

, there must be an element  in

in  such that product of

such that product of  and

and  is the identity element

is the identity element  ( in symbols, for each

( in symbols, for each  there is a

there is a  such that

such that  for every;

for every; ).

). - Commutative: In addition to the above four, if it so happens that

,

,  , then the group is called an Abelian Group. Otherwise it is called a non-Abelian group.

, then the group is called an Abelian Group. Otherwise it is called a non-Abelian group.

Symmetry group

In abstract algebra, the symmetry group of an object (image, signal, etc.) is the group of all isometries under which the object is invariant with composition as the operation. It is a subgroup of the isometry group of the space concerned.[1] In quantum mechanics, all transformations of a system that leave the Hamiltonian unchanged is the symmetry group of the Hamiltonian. The group operation is a binary multiplication operator.

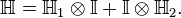

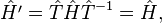

The symmetry operator commutes with the Hamiltonian, that is,

-

or,

or, -

thus

thus -

![[\hat{T},\hat{H}]=0=[\hat{H},\hat{T}]](../I/m/5b732581ea204af21cad9823d6f4a8b7.png)

The set of all  comprises a group, with the identity element being

comprises a group, with the identity element being  ——which corresponds to no transformation on the Hamiltonian. All transformations have an inverse. Thus, these form a group [2]

——which corresponds to no transformation on the Hamiltonian. All transformations have an inverse. Thus, these form a group [2]

The SU(3) group

The special unitary group SU is the group of unitary matrices whose determinant is equal to 1.[3] This set is closed under matrix multiplication. All transformations characterized by the special unitary group leave norms unchanged. The SU(3) symmetry appears in quantum chromodynamics, and, as already indicated in the light quark flavour symmetry dubbed the Eightfold Way (physics). The quarks possess colour quantum numbers and form the fundamental (triplet) representation of an SU(3) group.

The group SU(3) is a subgroup of group U(3), the group of all 3×3 unitary matrices. The unitarity condition imposes nine constraint relations on the total 18 degrees of freedom of a 3×3 complex matrix. Thus, the dimension of the U(3) group is 9. Furthermore, multiplying a U by a phase, eiφ leaves the norm invariant. Thus U(3) can be decomposed into a direct product of U(1)⊗SU(3). Because of this additional constraint, SU(3) has dimension 8.

Generators

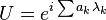

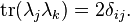

Every unitary matrix U can be written in the form

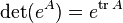

where H is hermitian. The elements of SU(3) can be expressed as

where  are the 8 linearly independent matrices forming the basis of the Lie algebra of SU(3), in the tripet representation. The unit determinant condition requires the

are the 8 linearly independent matrices forming the basis of the Lie algebra of SU(3), in the tripet representation. The unit determinant condition requires the  matrices to be traceless, since

matrices to be traceless, since

-

.

.

An explicit basis in the fundamental, 3, representation can be constructed in analogy to the Pauli matrix algebra of the spin operators. It consists of the Gell-Mann matrices,

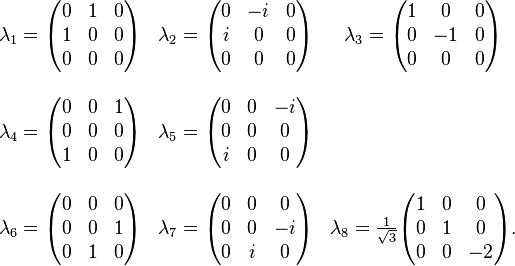

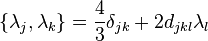

These are the generators of the SU(3) group in the triplet representation, and they are normalized as

The Lie algebra structure constants of the group are given by the commutators of

where  are the structure constants.

are the structure constants.  are antisymmetric and are analogous to the Levi-Civita symbol

are antisymmetric and are analogous to the Levi-Civita symbol  of SU(2).

of SU(2).

Moreover,

where  are the symmetric coefficient constants.

are the symmetric coefficient constants.

Standard basis

A slightly differently normalized standard basis consists of the F-spin operators, which are defined as  for the 3, and are utilized to apply to any representation of the algebra.

for the 3, and are utilized to apply to any representation of the algebra.

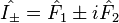

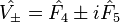

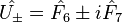

The standard form of basis of the Lie algebra of SU(3) can be obtained by another change of basis, where one defines,[4]

Commutation algebra of the generators

The standard form of generators of the SU(3) group follows the commutation relations given below:

All the other commutating relations follow from the hermiticity of the operators. These commutation relations can be used to construct the representations of the SU(3) group.

The representations of the group lie in the  plane. Here,

plane. Here,  stands for the z-component of Isospin and

stands for the z-component of Isospin and  is the Hypercharge. The maximum number of mutually commutating generators of a Lie algebra is called its rank: SU(3) has rank 2.

is the Hypercharge. The maximum number of mutually commutating generators of a Lie algebra is called its rank: SU(3) has rank 2.

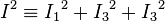

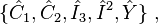

Casimir operators

The Casimir operator is an operator that commutes with all the generators of the Lie group. In the case of SU(2), the quadratic operator J2 is the only independent such operator.

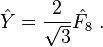

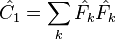

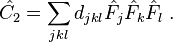

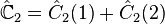

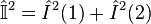

In the case of SU(3) group, by contrast, two independent Casimir operators can be constructed, a quadratic and a cubic: they are,[5]

These Casimir operators serve to label the irreducible representations of the Lie group algebra SU(3), because all states in a given representation assume the same value for each Casimir operator, which serves as the identity in a space with the dimension of that representation. This is because states in a given representation are connected by the action of the generators of the Lie algebra, and all generators commute with the Casimir operators.

For example, for the triplet representation, D(1,0), the eigenvalue of Ĉ1 is 4/3, and of Ĉ2, 10/9.

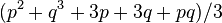

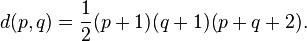

More generally, from Freudenthal's formula, for generic D(p,q), the eigenvalue[6] of Ĉ1 is  .

.

The eigenvalue ("anomaly coefficient") of Ĉ2 is[7]

It is an odd function under the interchange p↔q. Consequently, it vanishes for real representations p=q, such as the adjoint, D(1,1), i.e. both Ĉ2 and anomalies vanish for it.

It is an odd function under the interchange p↔q. Consequently, it vanishes for real representations p=q, such as the adjoint, D(1,1), i.e. both Ĉ2 and anomalies vanish for it.

Representations of the SU(3) group

The irreducible representations of SU(3) are denoted in the Dynkin basis by D(p,q), consisting of p quarks and q antiquarks (see section of Young tableaux below: p is the number of single-box columns and q the number of double-box columns); they have dimension

An SU(3) multiplet may be completely specified by five labels, two of which, the eigenvalues of the two Casimirs, are common to all members of the multiplet. This generalizes the mere two labels for SU(2) multiplets, namely the eigenvalues of its quadratic Casimir and of I3.

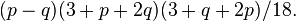

Since ![[\hat{I}_3,\hat{Y}]=0](../I/m/fc7f75b2d20389ea6a64ee96f36cd56a.png) , we can

label different states by the eigenvalues of

, we can

label different states by the eigenvalues of  and

and  operators,

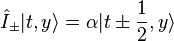

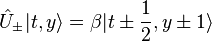

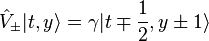

operators,  . The action of operators on this states are,[8]

. The action of operators on this states are,[8]

-

.jpeg) The representation of generators of the SU(3) group.

The representation of generators of the SU(3) group. -

-

-

-

-

-

Here,

and

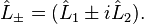

All the other states of the representation can be constructed by the successive application of the ladder operators  and

and  and by identifying the base states which are annihilated by the action of lowering operator. These operators lie on the vertices and the center of a hexagon.

and by identifying the base states which are annihilated by the action of lowering operator. These operators lie on the vertices and the center of a hexagon.

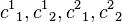

Clebsch–Gordan coefficient for SU(3)

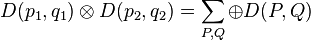

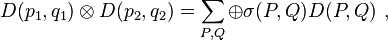

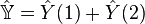

The product representation of two irreducible representations  and

and  is generally reducible. Symbolically,

is generally reducible. Symbolically,

where σ(P,Q) is an integer.

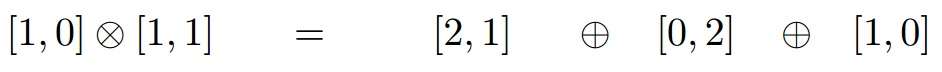

For example, two octets (adjoints) compose to

that is, their product reduces to an icosaseptet (27), decuplet, two octets, an antidecuplet, and a singlet, 64 states in all.

The right-hand series is called the Clebsch–Gordan series. It implies that the representation  appears

appears  times in the reduction of this direct product of

times in the reduction of this direct product of  with

with  . Now a complete set of operators is needed to specify uniquely the states of each irreducible representation inside the one just reduced.

. Now a complete set of operators is needed to specify uniquely the states of each irreducible representation inside the one just reduced.

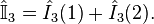

The complete set of commutating operators(CSCO) in the case of the irreducible representation  is

is

where

-

.

.

The states of the above direct product representation are thus completely represented by the set of operators

where the number in the bracket implies the representation to which the operator belongs.

An alternate set of commutating operators can be found for the direct product representation, if one considers the following operators,[9]

Thus, the set of commutating operators includes

This is a set of nine operators only. But the set must contain ten operators to define all the states of the direct product representation uniquely. To find the last operator  , one must look outside the group. It is necessary to distinguish different D(P,Q) for similar values of P and Q.

, one must look outside the group. It is necessary to distinguish different D(P,Q) for similar values of P and Q.

| Operator | Eigenvalue | Operator | Eigenvalue | Operator | Eigenvalue | Operator | Eigenvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

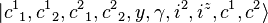

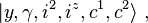

Thus, any state in the direct product representation can be represented by the ket,

also using the second complete set of commutating operator, we can define the states in the direct product representation as

We can drop the  from the state and label the states as

from the state and label the states as

using the operators from the first set, and,

using the operators from the second set.

Both these states span the direct product representation and any states in the representation can be labeled by suitable choice of the eigenvalues.

Using the completeness relation,

Here, the coefficients

are the Clebsch–Gordan coefficients.

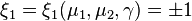

A different notation

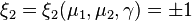

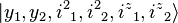

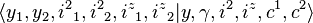

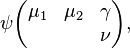

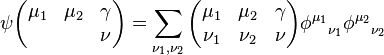

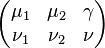

To avoid confusion, the eigenvalues  can be simultaneously denoted by μ and the eigenvalues

can be simultaneously denoted by μ and the eigenvalues  are simultaneously denoted by ν. Then the eigenstate of the direct product representation D(P,Q) can be denoted by[9]

are simultaneously denoted by ν. Then the eigenstate of the direct product representation D(P,Q) can be denoted by[9]

where  is the eigenvalues of

is the eigenvalues of  and

and  is the eigenvalues of

is the eigenvalues of  denoted simultaneously. Here, the quantity expressed by the parenthesis is the Wigner 3-j symbol.

denoted simultaneously. Here, the quantity expressed by the parenthesis is the Wigner 3-j symbol.

Furthermore,  are considered to be the basis states of

are considered to be the basis states of  and

and  are the basis states of

are the basis states of  . Also

. Also  are the basis states of the product representation. Here

are the basis states of the product representation. Here  represents the combined eigenvalues

represents the combined eigenvalues  and

and  respectively.

respectively.

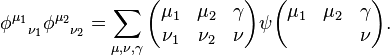

Thus the unitary transformations that connects the two bases are

This is a comparatively compact notation. Here,

are the Clebsch–Gordan coefficients.

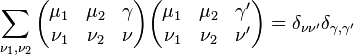

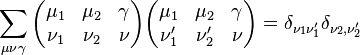

Orthogonality relations

The Clebsch–Gordan coefficients form a real orthogonal matrix. Therefore,

Also, they follow the following orthogonality relations,

Symmetry properties

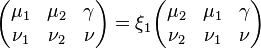

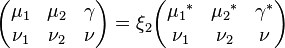

If an irreducible representation  apperars in the Clebsch–Gordan series of

apperars in the Clebsch–Gordan series of  , then it must appear in the Clebsch–Gordan series of

, then it must appear in the Clebsch–Gordan series of  . Which implies,

. Which implies,

Where

Since the Clebsch–Gordan coefficients are all real, the following symmetry property can be deduced,

Where  .

.

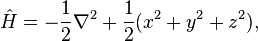

Symmetry group of the 3D oscillator Hamiltonian operator

A three-dimensional harmonic oscillator is described by the Hamiltonian

where the spring constant, the mass and Planck's constant have been absorbed into the definition of the variables, ħ=m=1.

It is seen that this Hamiltonian is symmetric under coordinate transformations that preserve the value of  . Thus, any operators in the group

. Thus, any operators in the group  keep this Hamiltonian invariant.

keep this Hamiltonian invariant.

More significantly, since the Hamiltonian is Hermitian, it further remains invariant under operation by elements of the much larger SU(3) group.

Proof that the symmetry group of linear isotropic 3D Harmonic Oscillator is  [10]

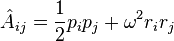

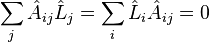

[10]A tensor operator analogous to the Laplace–Runge–Lenz vector for the Kepler problem may be defined,

which commutes with the Hamiltonian,

Since it commutes with the Hamiltonian, it represents a constant of motion. It has the following properties,

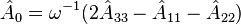

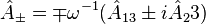

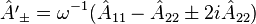

Apart from the tensorial trace of the operator

, which is the Hamiltonian, the remaining 5 operators can be rearranged into their spherical component form as

, which is the Hamiltonian, the remaining 5 operators can be rearranged into their spherical component form asAlso, the angular momentum operators are written in spherical component form as

They obey the following commutation relations,

The eight operators consisting of the 5 operators derived from the traceless symmetric tensor operator and the three independent components of the angular momentum vector have the same commutation relation as the infinitesimal operators of the

and the three independent components of the angular momentum vector have the same commutation relation as the infinitesimal operators of the  group.

group.As such, the symmetry group of Hamiltonian for a linear isotropic 3D Harmonic oscillator is isomorphic to

group.

group.-

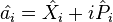

More systematically, operators such as the Ladder operators

-

and

and

can be constructed which raise and lower the eigenvalue of the Hamiltonian operator by 1.

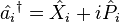

The operators  and

and  are not hermitian; but hermitian operators can be constructed from different combinations of them, namely

are not hermitian; but hermitian operators can be constructed from different combinations of them, namely

-

.

.

There are nine such operators for  .

.

The nine hermitian operators formed by the bilinear forms  are controlled by the fundamental commutators

are controlled by the fundamental commutators

and seen to not commute among themselves. As a result, this complete set of operators don't have their eigenvectors in common, and they cannot be diagonalized simultaneously. The group is thus non-Abelian and degeneracies may be present in the Hamiltonian, as indicated.

The Hamiltonian of the 3D isotropic harmonic oscillator, when written in terms of the operator  amounts to

amounts to

-

![\hat{H}=\omega\left[\frac{3}{2}+\hat{N_1}+\hat{N_2}+\hat{N_3}\right]](../I/m/5f97f61914aa0a49021bba67a041e383.png) .

.

The Hamiltonian has 8-fold degeneracy. A successive application of  and

and  preserves the Hamiltonian invariant, since it decreases

preserves the Hamiltonian invariant, since it decreases  by 1 and increase

by 1 and increase  by 1, thereby keeping the total

by 1, thereby keeping the total

constant.[11]

constant.[11]

The maximally commuting set of operators

Since the operators belonging to the symmetry group of Hamiltonian do not always form an Abelian group, a common eigenbasis cannot be found that diagonalizes all of them simultaneously. Instead, we take the maximally commuting set of operators from the symmetry group of the Hamiltonian, and try to reduce the matrix representations of the group into irreducible representations.

Hilbert space of two systems

The Hilbert space of two particles is the tensor product of the two Hilbert spaces of the two individual particles.

where  and

and  are the Hilbert space of the first and second particle respectively.

The operators in each of the Hilbert space has their own commutation relation and an operator of one Hilbert space commutes with an operator from different Hilbert space if the particles are indistinguishable. Thus the symmetry group of the two particle Hamiltonian operator is the superset of the symmetry groups of the Hamiltonian operators of individual particles. If the individual Hilbert spaces are N dimensional, the combined Hilbert space is N^2 dimensional.

are the Hilbert space of the first and second particle respectively.

The operators in each of the Hilbert space has their own commutation relation and an operator of one Hilbert space commutes with an operator from different Hilbert space if the particles are indistinguishable. Thus the symmetry group of the two particle Hamiltonian operator is the superset of the symmetry groups of the Hamiltonian operators of individual particles. If the individual Hilbert spaces are N dimensional, the combined Hilbert space is N^2 dimensional.

Clebsch–Gordan coefficient in this case

The symmetry group of the Hamiltonian is SU(3). As a result, the Clebsch–Gordan coefficients can be found by expanding the uncoupled basis vectors of the symmetry group of the Hamiltonian into its coupled basis. The Clebsch–Gordan series is obtained by block-diagonalizing the Hamiltonian through the unitary transformation constructed from the eigenstates which diagonalizes the maximal set of commuting operators.

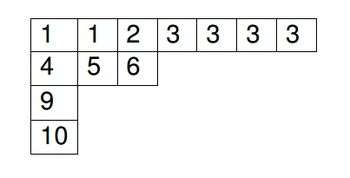

Young tableaux

A Young tableau (plural tableaux) is a method for decomposing products of an SU(n) group representation into a sum of irreducible representations. It provides the dimension and symmetry types of the irreducible representations, which is known as the Clebsch–Gordan series. Each irreducible representation corresponds to a single-particle state and a product of more than one irreducible representation indicates a multiparticle state. Since the particles are mostly indistinguishable in quantum mechanics, this approximately relates to several identical particles. The permutations of n identical particles constitute the symmetry group  . Every N-particle state of

. Every N-particle state of  that is made up of single-particle states of the fundamental n-dimensional SU(n) multiplet belongs to an irreducible SU(n) representation.

Thus it can be used to determine the Clebsch–Gordan series for any unitary group.[12]

that is made up of single-particle states of the fundamental n-dimensional SU(n) multiplet belongs to an irreducible SU(n) representation.

Thus it can be used to determine the Clebsch–Gordan series for any unitary group.[12]

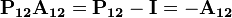

Constructing the states

Any two particle wavefunction , where the indices 1,2 represents the state of particle 1 and 2, can be used to generate states of explicit symmetry using the symmetrizing and the anti-symmetrizing operators.[13]

, where the indices 1,2 represents the state of particle 1 and 2, can be used to generate states of explicit symmetry using the symmetrizing and the anti-symmetrizing operators.[13]

where the  are the operator that interchanges the particles (Exchange operator).

are the operator that interchanges the particles (Exchange operator).

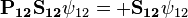

The following relation follows:[13]-

thus,

Starting from a multipartice state, we can apply  and

and  repeatedly to construct states that are:[13]-

repeatedly to construct states that are:[13]-

- Symmetric with respect to all particles.

- Antisymmetric with respect to all particles.

- Mixed symmetries, i.e. symmetric or antisymmetric with respect to some particles.

Constructing the tableaux

Instead of using  , in Young tableaux, we use squares

, in Young tableaux, we use squares  to denote particles and i to denote the state of the particles.

to denote particles and i to denote the state of the particles.

The complete set of  particles are denoted by arrangement of

particles are denoted by arrangement of  . Each with its own quantum number label(i).

. Each with its own quantum number label(i).

The tableaux is formed by stacking boxes side by side by side and up-down such that the states symmetrised with respect to all particles are given ia a row and the states anti-symmetrised with respect to all particles lies in a single column. Following rules are followed while constructing the tableaux:[12]

- A row must not be longer than the one before it.

- The quantum labels (numbers in the

) should not decrease while going left to right in a row.

) should not decrease while going left to right in a row. - The quantum labels must strictly increase while going down in a column.

Case for n = 3

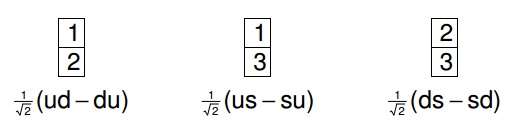

For n=3 that is in the case of SU(3), the following situation arises. In SU(3) there are three labels, they are generally designated by (u,d,s) corresponding to up, down and strange quarks which follows the SU(3) algebra. They can also be designated generically as (1,2,3). For two particle system, we have the following six symmetry states:

and the following three antisymmetric states:

The 1-column, 3-row tableau is the singlet, and so all tableaux of nontrivial irreps of SU(3) cannot have more than two rows. The representation D(p,q) has p+q boxes on the top row and q boxes on the second row.

Clebsch–Gordan series from the tableaux

Clebsch–Gordan series is the expansion of the direct product of two irreducible representgation in to direct sum of irreducible representations.

. This can be easily found out from the Young tableaux.

. This can be easily found out from the Young tableaux.

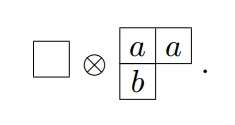

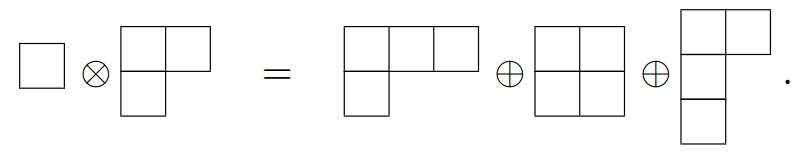

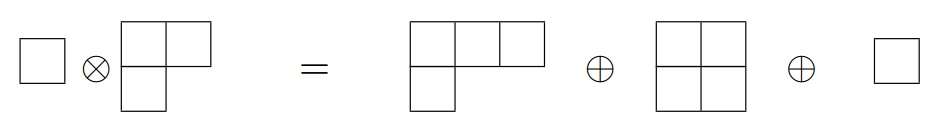

Procedure to obtain the Clebsch–Gordan series from Young tableaux: The following steps are followed to construct the Clebsch–Gordan series from the Young tableaux:[14]

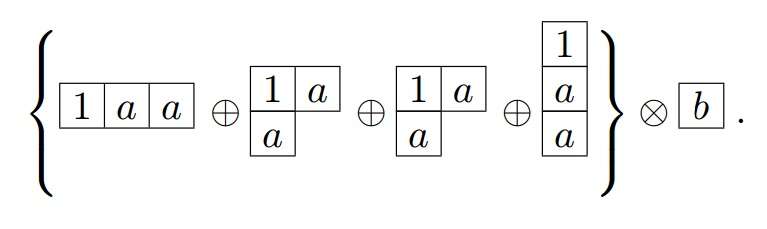

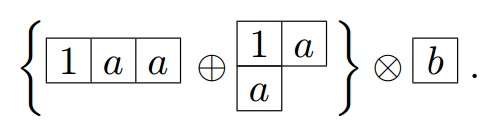

- Write down the two Young diagrams for the two irreps under consideration, such as in the following example. In the second figure insert a series of the letter a in the first row, the letter b in the second row, the letter c in the third row, etc. in order to keep track of them once they are included in the various resultant diagrams:

- Take the first box containing an a and appends it to the first Young diagram in all possible ways that follow the rules for creation of a Young diagram:

- Then take the next box containing an a and do the same thing with it, except that we are not allowed to put two a’s together in the same column.

The last diagram in the curly bracket contains two a in the same column thus the diagram must be deleted. Thereby giving:

- Append the last box to the diagram in curly bracket in all possible ways resulting in:

- In each rows while counting from right to left, if at any point the number of a particular alphabet encountered be more than the number of the previous alphabet, then the diagram must be deleted. Here the first and the third diagram should be deleted, resulting in:

Example of Clebsch–Gordan series for SU(3)

The tensor product of a triplet with an octet reducing to a deciquintuplet (15), an anti-sextet, and a triplet

appears diagrammatically as[14]-

a total of 24 states. Using the same procedure, any direct product representation is easily reduced.

See also

References

- ↑ Group Theory and its Application to Physical Problems-Morton Hammermesh, ISBN 13978-0486661810, Chapter-2

- ↑ http://www.phys.nthu.edu.tw/~class/Group_theory/Chap%201.pdf

- ↑ P. Carruthers (1966) Introduction to Unitary symmetry, Interscience. online.

- ↑ Introduction to Elementary Particles- David J. Griffiths, ISBN 978-3527406012, Chapter-1, Page33-38

- ↑ Bargmann, V.; Moshinsky, M. (1961). "Group theory of harmonic oscillators (II). The integrals of Motion for the quadrupole-quadrupole interaction". Nuclear Physics 23: 177. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(61)90253-X.

- ↑ Pais, A. (1966). "Dynamical Symmetry in Particle Physics". Reviews of Modern Physics 38 (2): 215. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.38.215., (3.65)

- ↑ Pais, ibid. (3.66)

- ↑ http://www.ks.uiuc.edu/Services/Class/PHYS480/qm_PDF/chp12.pdf

- 1 2 De Swart, J. J. (1963). "The Octet Model and its Clebsch-Gordan Coefficients". Reviews of Modern Physics 35 (4): 916. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.35.916. , De Swart, J. (1965). "Erratum: The Octet Model and Its Clebsch-Gordan Coefficients". Reviews of Modern Physics 37 (2): 326. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.37.326.; online

- ↑ http://scitation.aip.org/content/aapt/journal/ajp/33/3/10.1119/1.1971373

- ↑ http://theory.tifr.res.in/~sgupta/courses/qm2014/lec13.pdf

- 1 2 Mathematical Methods for Physicists by George B. Arfken, Hans J. Weber. Sixth edition- Chapter 4

- 1 2 3 http://hepwww.rl.ac.uk/Haywood/Group_Theory_Lectures/Lecture_4.pdf

- 1 2 http://physics.unm.edu/Courses/Finley/p467/handouts/YoungTableauxSubs.pdf

- Greiner, W.; Müller, B. (1994). Quantum Mechanics: Symmetries (2nd ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-3540580805.

- McNamee, P.; j., S.; Chilton, F. (1964). "Tables of Clebsch-Gordan Coefficients of SU3". Reviews of Modern Physics 36 (4): 1005. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.36.1005.

External links

- Clebsch–Gordan coefficients for SU(3) using simple symmetries

- An online program to generate the Clebsch–Gordan coefficients for SU(N) group

![[\lambda_j,\lambda_k]=2if_{jkl}\lambda_k ~,](../I/m/effa2b80f18c6eb1bbbcc1f1f2470a5c.png)

![[\hat{Y},\hat{I}_3]=0,](../I/m/8a4eb45bb539a0e06da3c8f6496dc350.png)

![[\hat{Y},\hat{I}_\pm]=0,](../I/m/a3e3041f57046afb3b4a0fd7eb5d1ee3.png)

![[\hat{Y},\hat{U}_\pm]=\pm \hat{U_\pm},](../I/m/88c21d82463dc2509fe1c5a089bdefc7.png)

![[\hat{Y},\hat{V}_\pm]=\pm \hat{V_\pm},](../I/m/0e16abfef340aeecc96dd3a1ca95c99b.png)

![[\hat{I}_3,\hat{I}_\pm]=\pm \hat{I_\pm},](../I/m/3954069e68422b7469042eb58545bef7.png)

![[\hat{I}_3,\hat{U}_\pm]=\mp\frac{1}{2}\hat{U_\pm},](../I/m/1f9b555a48c26d1595865e4494d0bdda.png)

![[\hat{I}_3,\hat{V}_\pm]=\pm \frac{1}{2}\hat{V_\pm},](../I/m/ebb5ecf4b5a2567cc633054f66ebadc5.png)

![[\hat{I}_+,\hat{I}_-]= 2\hat I_3,](../I/m/223f90ac32b55756092495ecf4a8a077.png)

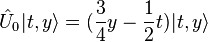

![[\hat{U}_+,\hat{U}_-]= \frac{3}{2}\hat{Y}-\hat{I}_3,](../I/m/0b018154a942a51dac65fe0d73e58600.png)

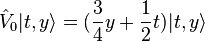

![[\hat{V}_+,\hat{V}_-]= \frac{3}{2}\hat{Y}+\hat{I}_3,](../I/m/16f3695cecc0a4ad1e2ddfe9f07d5788.png)

![[\hat{I}_+,\hat{V}_-]= -\hat U_-,](../I/m/e9f224a193939e471571d9681d14cd42.png)

![[\hat{I}_+,\hat{U}_+]= \hat V_+,](../I/m/beb91158825a9ff5445aa93ca53448e8.png)

![[\hat{U}_+,\hat{V}_-]= \hat I_-,](../I/m/0b454692d85025ab93f5a23037cacd01.png)

![[\hat{I}_+,\hat{V}_+]= 0,](../I/m/368807acdd2bc8eba2aa35a6e95f496a.png)

![[\hat{I}_+,\hat{U}_-]= 0,](../I/m/ec8c8c3cc27b883c2f89aba139e52257.png)

![[\hat{U}_+,\hat{V}_+]= 0.](../I/m/ad201fdcbfc0b95a3014ae6de0735559.png)

![\hat{U}_0\equiv \frac{1}{2}[\hat{U}_+,\hat{U}_-]=\frac{3}{4}\hat{Y}-\frac{1}{2}\hat{I}_3](../I/m/ea3728b97b3db9f1af248cf6422df3d5.png)

![\hat{V}_0\equiv \frac{1}{2}[\hat{V}_+,\hat{V}_-]=\frac{3}{4}\hat{Y}+\frac{1}{2}\hat{I}_3.](../I/m/ef2a7165da0ede25bc4b5b758de592fc.png)

![[\hat{A}_{ij},\hat{H}]=0.](../I/m/5afaa39c3e35fbbded106be6146863a2.png)

![\sum_j\hat{A}_{ij}\hat{A}_{jk}=\hat{H}\hat{A}_{ik}+\frac{1}{4}\omega^2\{\hat{L}_i\hat{L}_k-\delta_{ik}\hat{L}^2+2[\hat{L}_i,\hat{L}_k]-2\hbar^2\delta_{ik}\}](../I/m/13c2b977f495b2a12d08242a67ad6ddc.png)

![Tr[\hat{A}_{ij}]=\sum_i{\hat{A}_{ii}}=\hat{H}.](../I/m/721179497eeb6899886b69cae05f6bdf.png)

![[\hat{L}_{3},\hat{A}_{0}]=[\hat{A}_{0},\hat{A'}_{\pm}]=[\hat{A}_{\pm},\hat{A'}_{\pm}]=[\hat{L}_{\pm},\hat{A'}_{\pm}]](../I/m/41ef388a1b39e36ff731274f5821a807.png)

![[\hat{L}_{\pm},\hat{L}_{\mp}]=-4[\hat{A}_{\pm},\hat{A}_{\mp}]=\frac{1}{2}[\hat{A'}_{\pm},\hat{A'}_{\mp}]=\pm2\hbar\hat{L}_3](../I/m/3bee4f08685e59e408c1ceacbf471d9c.png)

![[\hat{L}_{\pm},\hat{A}_{\mp}]=\hbar\hat{A}_0](../I/m/de677d28a2db312f3f648f44421a61e7.png)

![\pm[\hat{L}_{3},\hat{L}_{\pm}]=-\frac{2}{3}[\hat{A}_{0},\hat{A}_{\pm}]=[\hat{A}_{\mp},\hat{A'}_{\pm}]=\hbar\hat{L}_{\pm}](../I/m/ab5472d3302f654a00410dc2e6fff8f6.png)

![\pm[\hat{L}_{3},\hat{A}_{\pm}]=-\frac{1}{6}[\hat{A}_{0},\hat{L}_{\pm}]=\frac{1}{4}[\hat{L}_{\mp},\hat{A'}_{\pm}]=\hbar\hat{A}_{\pm}](../I/m/472d79235ce8fd1ee23b040cee5a8816.png)

![\pm[\hat{L}_{3},\hat{A'}_{\pm}]=2[\hat{L}_{\pm},\hat{A}_{\pm}]=2\hbar\hat{A'}_{\pm}.](../I/m/889b9269f937e1a0120b771d2256c6c6.png)

![[\hat{a_i},\hat{a_j}^\dagger]=2i\delta_{ij},](../I/m/b238bcbf66251cc0e010afc5e051de3f.png)

![[\hat{a_i},\hat{a_j}]=[\hat{a_i}^\dagger,\hat{a_j}^\dagger]=0,](../I/m/6e1d876d4883ee964550fe3dbcaa2e0f.png)