Clark County, Arkansas

| Clark County, Arkansas | |

|---|---|

_001.jpg) Clark County Courthouse in Arkadelphia | |

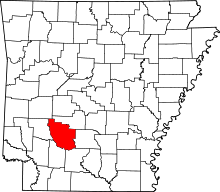

Location in the state of Arkansas | |

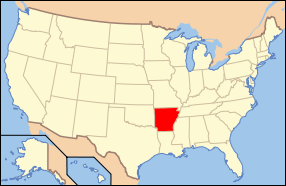

Arkansas's location in the U.S. | |

| Founded | December 15, 1818 |

| Named for | William Clark |

| Seat | Arkadelphia |

| Largest city | Arkadelphia |

| Area | |

| • Total | 883 sq mi (2,287 km2) |

| • Land | 866 sq mi (2,243 km2) |

| • Water | 17 sq mi (44 km2), 1.9% |

| Population | |

| • (2010) | 22,995 |

| • Density | 27/sq mi (10/km²) |

| Congressional district | 4th |

| Time zone | Central: UTC-6/-5 |

| Website |

www |

Clark County is a county located in the U.S. state of Arkansas. As of the 2010 census, the population was 22,995.[1] The county seat is Arkadelphia.[2]

The Arkadelphia, AR Micropolitan Statistical Area includes all of Clark County.

History

Clark County was Arkansas' third county, formed on December 15, 1818, alongside Hempstead and Pulaski counties. The county is named after William Clark who at the time was Governor of the Missouri Territory, which included present-day Arkansas. Arkadelphia was named as the county seat in 1842.

Civil War era

Clark County was very active in its support of the Confederacy during the Civil War, both in its maintaining an arsenal to manufacture arms, as well as large numbers of Clark County men going off to serve in the army. At the outbreak of the war, in May, 1861, the artillery battery, 2nd Arkansas Light Artillery, was organized for service in the Confederate Army. Recruited for and organized in Arkadelphia by local watch maker Franklin Roberts, who would serve as the battery's captain, the battery would later be commanded by Captain Jannedens H. Wiggins, and would see considerable action while under the command of General Nathan Bedford Forrest. Of the more than 160 men who served in the battery, most of whom were from Clark County, only 11 remained at the time of its surrender on April 19, 1865, the rest having been killed, wounded or captured.

Most of the Clark County men who joined the Confederate Army enlisted into the 1st Arkansas Infantry, which served under Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard, as a part of the Army of Tennessee. The state of Arkansas formed some 48 infantry regiments during the war, along with several cavalry units, with the most famous being the 3rd Arkansas of the Army of Northern Virginia. With the exception of the 3rd Arkansas, no other regiment from the state served for the duration of the war in the "eastern theater", but instead were assigned in the "western theater", which was the case with the 1st Arkansas. Of the 48 infantry regiments formed by Arkansas, the most active was the 3rd Arkansas and the 1st Arkansas, followed by the 1st Arkansas Mounted Rifles and the 4th Arkansas. The 1st Arkansas fought in the Battle of Shiloh, Battle of Murfreesboro, Battle of Chickamauga, Battle of Chattanooga, Battle of Franklin, Battle of Perryville and the Battle of Bentonville in North Carolina, along with several other minor battles.

Most of the men of Clark County served in "B Company", commanded by county residents Captain Charles S. Stark, 1st Lieutenant George W. McIntosh, and 2nd Lieutenants Frederick M. Greene and William E. Lindsey. Two Clark County men, both serving in "B Company", were awarded the Confederate Medal of Honor. Both medals were awarded for bravery in action during the Battle of Chickamauga. They were Lieutenant Andrew J. Pitner, who was killed in action and whose medal was posthumous, and Private Charles Trickett, who survived the battle, dying in 1939. The regiment was with the Army of Tennessee when it surrendered in Greensboro, North Carolina on April 26, 1865.[3]

The Confederacy employed the use of numerous arsenals during the war. One of those was located in Arkadelphia. That arsenal manufactured large quantities of ammunition and rifles, as well as a newer version of previous muzzle loaded rifles. This newer version of rifle, called the "Arkadelphia Rifle", came toward the end of the war, and was initially believed to be superior to previous versions. However, in its limited use, it proved to be no more reliable than any previous versions, and in some cases was reported to be insufficient. One of these "Arkadelphia Rifle"s is on display at the Civil War Museum in Washington, Arkansas.[4] There were numerous pro-Confederate guerrilla bands operating in Clark County, but short of minor skirmishes, one of which is registered with the National Register of Historic Places, there were no major military actions in Clark County. The closest that Union forces came to Clark County was during Major General Frederick Steele's Camden Expedition.[5]

1865 and later

Following the war, the economy was devastated, as was most of the south. From 1859 through 1868 the county had been home to a school for the blind, one of the few education centers to remain open during the war. In 1873 the Cairo and Fulton railroad line connected Arkadelphia and Little Rock. This helped to generate the economy, and bolster the logging industry, eventually leading to Graysonia, Arkansas becoming a thriving mill town, along with the towns of Amity and Gurdon who also became dependent on the logging industry. In 1889, James H. Abraham was appointed Sheriff by Arkansas Governor Simon Pollard Hughes, Jr., following the death of former Sheriff Joseph Hulsey. Abraham would hold that position through regular election for the next 25 years, the longest sheriffs term in Clark County history. It would be Abraham who investigated and ultimately arrested Benjamin Standford for the 1893 murder of Hans Sellars, despite Standford's claim of self defense.[6] Of the five men who were sentenced to death in Clark County that actually had their death sentences carried out, four would be during Abraham's tenure, and the fifth during the year of his death.[7]

Education was segregated during this period, with two colleges (Arkadelphia Methodist College and Ouachita Baptist College) opening for white people, and two schools (Bethel AME and Presbyterian Industrial School) opening for African-Americans. Segregation would become a problem in Clark County during the early and mid-20th century. Racial tensions in Clark County would build over the years following the end of the Civil War, with one African-American man being lynched in Arkadelphia on October 7, 1900.[8] Eventually the tensions resulted in riots in the Arkadelphia schools during 1968.

On December 18, 1914 Arthur Hodges became the first person in Clark County to be executed by use of the electric chair. Prior to that, the primary way of execution was either by hanging or firing squad. It was the 314th documented execution in Arkansas history, the fourth by electrocution. He was executed for the 1913 murder of Clark County Constable Morgan Garner. The execution was the subject of an article by The Kansas City Star entitled "Eight to die in Arkansas", making reference to eight men being executed in Arkansas over a sixteen-day period. Although Clark County has sentenced many to death in its history, only five, including Hodges, were executed, four for the crime of murder and one for the crime of rape. The other four were Louie McBryde, Willis Green, Anderson Mitchell, and Daniel Jones, the latter three being hanged together on March 15, 1889, for the murder of local preacher Arthur Horton. These statistics do not include lynchings, which were not common in 19th century Clark County, nor does it include firing squad executions committed during the Civil War era.

Clark County Constable Morgan Garner was the second police officer in a two-year time frame to be killed in Clark County, the other being the 1912 murder of Gurdon Town Marshal I.Y. Nash. Nash was killed by his own deputy, Sam Arnott, after the two became involved in an argument which escalated into a physical altercation, which resulted in a brief shootout during which Nash was shot twice and killed. That altercation was a result of Marshal Nash demanding the resignation of Arnott. Both murders took place during Sheriff Abraham's tenure as sheriff.[9][10]

Great Depression

The discovery of cinnabar in the foothills of the Ouachita Mountains, mostly south of Amity, sparked the 1931 Quicksilver Rush. This sparked a boost in employment opportunities, which was badly needed due to the Great Depression. However, it was short-lived, as cinnabar became more readily accessible from other sources. By 1940 any significant mining had ended. However, with the outbreak of World War II, large numbers of Clark County men went off to the military for service. In 1943, the county conducted a local option election pursuant to Initiated Act No. 1 of 1942,[11] and the electorate voted to ban the retail sale of alcohol in the county.

In 1966, wealthy businesswoman and philanthropist Jane Ross and her mother Esther Clark Ross founded the "Ross Foundation", a foundation concentrating primarily on educational assistance. To date that organization has contributed in excess of $10,000,000 to local charities and educational programs, in addition to other projects. In 1972 she also helped found the "Clark County Historical Association". The county has thirty seven locations listed with the National Register of Historic Places, to include the Clark County Courthouse, Magnolia Manor, and the Captain Charles C. Henderson House. U.S. Route 67 was a main highway leading through Clark County, bolstering hotels and businesses along that route. In the mid-1960s I-30 was completed, dooming the small businesses who were by that time dependent on the constant US 67 traffic. However, with the interstate came other business, and the city of Arkadelphia began to thrive. DeGray Lake was completed by 1972, giving the county a small tourist industry in that realm.[12]

Tornado disaster of 1997

On March 1, 1997, a tornado in the F-4 category ripped through Clark County in a north eastern direction, causing major damage to much of the county, including heavy damage to the downtown portion of Arkadelphia. The tornado also heavily damaged other parts of the state. By later media accounts, Arkadelphia was the hardest hit that day.[13] The event was on such a scale that it prompted a visit and tour by US President Bill Clinton on March 4, 1997. That one tornado resulted in 6 people being killed and 113 injured in Clark County alone, with 25 deaths statewide. The local police and fire departments were commended for their quick response during and immediately following the tornado, and the Arkansas Army National Guard were deployed to assist in preventing looting and evacuate victims. The disaster prompted a recovery program that assisted with housing and medical support, with the American Red Cross and press agencies from across the country converging on the county seat.[14][15][16][17]

The county formed the "2025 Commission", responsible for planning and organizing the recovery efforts. The commission included state Senator Percy Malone, who was later credited with having been a driving force behind the recovery efforts. A 40 block area of Arkadelphia had been destroyed, better than 60% of the downtown area alone, along with property damage totalling in the millions of dollars county wide.[18] Within a decade, the county and city of Arkadelphia were commended for their recovery efforts, having repaired or rebuilt almost every building affected by the storm, and with the downtown portion of Arkadelphia thriving beyond its former success.[19] Due to the tornado of March 1, 1997, Arkadelphia was the first community in Arkansas to participate in the "Project Impact" initiative of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Arkadelphia installed shatter proof windows in all its schools, purchased a 10-kilowatt generator, improved its drainage systems to help prevent flooding, and designed and built a "safe building" capable of holding 900 people at the Peake Elementary School.[20]

Wet/Dry Ballot Initiative

Clark County voted dry in 1943. In the mid-2000s, a group of local citizens began planning a local option petition drive for the 2006 election cycle but failed to make the ballot. In 2008, a committee having many of the same members succeeded in getting the issue on the ballot. However, the day before the general election, the Arkansas Supreme Court ruled that some of the petition's signatures had been gathered improperly and directed the Clark County Clerk not to count the ballots.[21] The committee was successful in getting the local option issue on the ballot in the 2010 general election, and the measure passed 56% to 44%.[22]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 883 square miles (2,290 km2), of which 866 square miles (2,240 km2) is land and 17 square miles (44 km2) (1.9%) is water.[23]

Major highways

.svg.png) Interstate 30

Interstate 30 U.S. Highway 67

U.S. Highway 67 Highway 7

Highway 7 Highway 8

Highway 8 Highway 26

Highway 26 Highway 51

Highway 51 Highway 53

Highway 53

Adjacent counties

- Hot Spring County (northeast)

- Dallas County (east)

- Ouachita County (southeast)

- Nevada County (southwest)

- Pike County (west)

- Montgomery County (northwest)

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1830 | 1,369 | — | |

| 1840 | 2,309 | 68.7% | |

| 1850 | 4,070 | 76.3% | |

| 1860 | 9,735 | 139.2% | |

| 1870 | 11,953 | 22.8% | |

| 1880 | 15,771 | 31.9% | |

| 1890 | 20,997 | 33.1% | |

| 1900 | 21,289 | 1.4% | |

| 1910 | 23,686 | 11.3% | |

| 1920 | 25,632 | 8.2% | |

| 1930 | 24,932 | −2.7% | |

| 1940 | 24,402 | −2.1% | |

| 1950 | 22,998 | −5.8% | |

| 1960 | 20,950 | −8.9% | |

| 1970 | 21,537 | 2.8% | |

| 1980 | 23,326 | 8.3% | |

| 1990 | 21,437 | −8.1% | |

| 2000 | 23,546 | 9.8% | |

| 2010 | 22,995 | −2.3% | |

| Est. 2014 | 22,576 | [24] | −1.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[25] 1790–1960[26] 1900–1990[27] 1990–2000[28] 2010–2014[1] | |||

As of the 2000 United States Census,[30] there were 23,546 people, 8,912 households, and 5,819 families residing in the county. The population density was 27 people per square mile (10/km²). There were 10,166 housing units at an average density of 12 per square mile (5/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 74.28% White, 22.02% Black or African American, 0.46% Native American, 0.62% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 1.37% from other races, and 1.20% from two or more races. 2.40% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 8,912 households out of which 29.80% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.80% were married couples living together, 12.20% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.70% were non-families. 27.60% of all households were made up of individuals and 12.40% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 2.91.

In the county the population was spread out with 21.70% under the age of 18, 20.00% from 18 to 24, 23.80% from 25 to 44, 19.90% from 45 to 64, and 14.60% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 32 years. For every 100 females there were 92.70 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.90 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $28,845, and the median income for a family was $37,092. Males had a median income of $28,692 versus $19,886 for females. The per capita income for the county was $14,533. About 13.50% of families and 19.10% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.90% of those under age 18 and 18.40% of those age 65 or over.

Communities

Cities

- Amity

- Arkadelphia (county seat)

- Gurdon

Towns

Unincorporated communities

Townships

Note: Unlike most Arkansas counties, Clark County only has one single township. That township encompasses the entire county.

Townships in Arkansas are the divisions of a county. Each township includes unincorporated areas; some may have incorporated cities or towns within part of their boundaries. Arkansas townships have limited purposes in modern times. However, the United States Census does list Arkansas population based on townships (sometimes referred to as "county subdivisions" or "minor civil divisions"). Townships are also of value for historical purposes in terms of genealogical research. Each town or city is within one or more townships in an Arkansas county based on census maps and publications. The townships of Clark County are listed below; listed in parentheses are the cities, towns, and/or census-designated places that are fully or partially inside the township. [31][32]

- Caddo

Notable residents

- The Clark County town of Alpine was once a childhood home to Hollywood film star Billy Bob Thornton.

- Dallas Cowboys NFL great Cliff Harris played his college football for the Ouachita Baptist University football team.

- Though raised in Hot Spring County, Arkansas, rising country music star Jody Evans got his start in Clark County, and works for the Arkadelphia Police Department.

- Actor Daniel Davis, best known for playing "Niles the butler" in the television series The Nanny, was born in Gurdon.

- Two modern politicians had roots in Arkadelphia: former Lieutenant Governor Bob C. Riley, a Democrat who served from 1971–1975, and Jerry Thomasson, a former member of the Arkansas House of Representatives who switched to the Republican Party to run unsuccessfully for state attorney general in 1966 and 1968.

- Rex Nelson, former Political Editor of the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, was born and raised in Arkadelphia.

See also

- List of lakes in Clark County, Arkansas

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Clark County, Arkansas

References

- 1 2 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ Amtour.net

- ↑ CWbullet.net

- ↑ Siftingsherald.com

- ↑ archiver.rootsweb.com

- ↑ Users.bestweb.net

- ↑ Ourtimepress.com

- ↑ Fastcase.com

- ↑ Fastcase.com

- ↑ Ark. Code Ann. § 3-8-201 et seq., Initiated Act No. 1 of 1942, 1 January 1943

- ↑ Encyclopediaofarkansas.net

- ↑ NCDC.noaa.gov

- ↑ USAtoday.com

- ↑ Weather.gov

- ↑ Camiros.com

- ↑ Ardemaz.com

- ↑ DRJ.com

- ↑ Planning.org

- ↑ News-leader.com

- ↑ Mays v. Cole, 374 Ark. 532 (Ark. 3 November 2008) (“To summarize, we hold that the circuit judge erred in construing the relevant provisions of the Arkansas Constitution and statutes to allow persons to sign the petition before they became registered voters. We, therefore, reverse the circuit court's ruling and set aside the certification of the question regarding the sale of alcoholic beverages in Clark County for placement on the November 4, 2008 ballot. We further direct that no votes cast on this question be counted.”).

- ↑ Phelps, Joe (3 November 2010). "County goes 'wet'". The Daily Siftings Herald.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2014". Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ↑ Based on 2000 census data

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ↑ 2011 Boundary and Annexation Survey (BAS): Clark County, AR (PDF) (Map). U. S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-08-23.

- ↑ "Arkansas: 2010 Census Block Maps - County Subdivision". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

External links

- Confederate Medal of Honor

- 1st Arkansas Infantry Regiment, CSA, Company B

- Lt. Andrew J. Pitner and Pvt. Charles Trickett, CSA Medal of Honor

- Stanford-Sellers murder, 1893

- Sheriff James H. Abraham

- Jane Ross

- Indictment, Green, Mitchell, Jones vs State of Arkansas, Clark County

- Encyclopedia of Arkansas

|

Hot Spring County |  | ||

| Pike County | |

Dallas County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Nevada County | Ouachita County |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 34°05′20″N 93°09′50″W / 34.08889°N 93.16389°W