Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War

Washington, D.C., during the American Civil War was a significant civilian leadership, military headquarters, and logistics center. As the capital of the United States, defending the city and the District of Columbia (which were not co-terminous at the time) became a major priority of the War Department, and often dictated military strategy. In many ways, the war transformed Washington from a rather modest, semi-rural city into an urban center of national importance as population, government, infrastructure, public and private buildings, and visitation all dramatically increased during the conflict. This set the stage for the rapid expansion of the city throughout the latter half of the 19th century.

Washington, D.C., during the early stages of the War

Despite being the nation's capital, Washington remained a small city of a few thousand residents, virtually deserted during the torrid summertime, until the outbreak of the Civil War. In February 1861, the Peace Congress, a last-ditch attempt by delegates from 21 of the 34 states to avert what many saw as the impending Civil War, met in the city's Willard Hotel. The strenuous effort failed and the War started in April 1861.

Faced with a legal procedure called "secession" that had turned hostile, President Abraham Lincoln began organizing a military force to protect Washington. The Confederates desired to take Washington in order to end the war quickly and gain independence. On April 10 forces began to trickle into the city. On April 19, the Baltimore riot threatened the arrival of further reinforcements. Led by Andrew Carnegie, a railroad was built circumventing Baltimore, allowing soldiers to arrive on April 25, thereby saving the capital.

Thousands of raw volunteers (as well as many professional soldiers) came to the area to fight for the Union. By the mid-summer, Washington teemed with volunteer regiments and artillery batteries from throughout the North, all serviced by what was little more than a country town of what had been in 1860, 75,800 people.[b] George Templeton Strong's observation of Washington life led him to declare

Of all the detestable places Washington is first. Crowd, heat, bad quarters, bad fair [fare], bad smells, mosquitos, and a plague of flies transcending everything within my experience... Beelzebub surely reigns here, and Willard's Hotel is his temple.

The city became the staging area for what became the Manassas Campaign. When Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell's beaten and demoralized army staggered back into Washington after the stunning Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run, the realization came that the war might be prolonged, and efforts began to fortify the city in case of a Confederate assault. Lincoln knew he had to have a professional and trained army to protect the Capital area, and therefore began by organizing the Department on the Potomac on August 4, 1861,[1] and the Army of the Potomac 16 days later.[2]

Most Washington citizens embraced the arriving troops, although there were pockets of apathy and Southern sympathy. Upon hearing a Union regiment singing "John Brown's Body" as the soldiers marched beneath her window, resident Julia Ward Howe wrote the patriotic "Battle Hymn of the Republic" to the same tune.

The significant expansion of the federal government to administer the ever-expanding war effort – and its legacies, such as veterans' pensions – led to notable growth in the city's population, especially in 1862 and 1863 when the military forces and the supporting infrastructure dramatically expanded from early war days. The 1860 Census put the population at just over 75,000 persons, but by 1870 the District population had grown to nearly 132,000. Warehouses, supply depots, ammunition dumps, and factories were established to provide and distribute materiel for the Federal armies, and civilian workers and contractors flocked to the city.

Slavery was abolished throughout the District on April 16, 1862 — eight months before Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation — with the passage of the Compensated Emancipation Act.[3] Washington became a popular place for freed slaves to congregate, and many were employed in constructing the ring of fortresses that eventually surrounded the city.

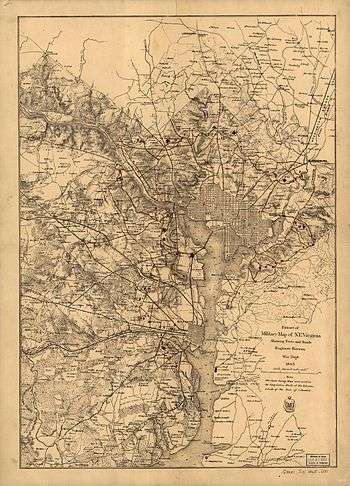

Defending the capital

At the beginning of the war, Washington's only defense was one old fort (Fort Washington, 12 miles (19 km) away to the south), and the Union Army soldiers themselves.[4] When Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan assumed command of the Department of the Potomac on August 17, 1861, he became responsible for the capital's defense.[1] McClellan began by laying out lines for a complete ring of entrenchments and fortifications that would cover 33 miles (53 km) of land. He built enclosed forts on high hills around the city, and placed well protected batteries of field artillery in the gaps between these forts,[5] augmenting the 88 guns already placed on the defensive line facing Virginia and south.[6] In between these batteries interconnected rifle pits were dug, allowing highly effective co-operative fire.[5] This layout, once complete, would make the city one of the most heavily-defended locations in the world, and almost unassailable by nearly any number of men.[4]

The capital's defenses for the most part deterred the Confederate Army from attacking. One notable exception was the Battle of Fort Stevens on July 11–12, 1864, in which Union soldiers repelled troops under the command of Confederate Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early. This battle was the first time since the War of 1812 that a U.S. president came under enemy fire during wartime when Lincoln visited the fort to observe the fighting.

By 1865 the defenses of Washington were most stout, amply covering both land and sea approaches. At war's end the now 37 miles (60 km) of line included at least 68 forts, over 20 miles (32 km) of rifle pits, and were supported by 32 miles (51 km) of military use only roads and four individual picket stations. 93 separate batteries of artillery had been placed on this line, comprising over 1,500 guns, both field & siege varieties, as well as mortars.[4]

D.C. Military formations

- Owens Company, District of Columbia cavalry {3 months unit-1861}

- 8 Battalions, District of Columbia Infantry {3 months unit-1861}

- 1st Regiment, District of Columbia Infantry

- 2nd Regiment, District of Columbia Infantry

- Unassigned District of Columbia Colored

- Unassigned District of Columbia Volunteers

Washington, D.C., during the later stages of the War

Hospitals in the Washington area became significant providers of medical services to wounded soldiers needing long-term care after being transported to the city from the front lines. Among the most significant of these Civil War hospitals were the Armory Square Hospital, Finley Hospital, and the Campbell Hospital. More than 20,000 injured or ill soldiers received treatment in an array of permanent and temporary hospitals in the capital, including the U.S. Patent Office, and, for a time, the Capitol itself. Among the notables who served in nursing were American Red Cross founder Clara Barton, and Dorothea Dix, who served as superintendent of female nurses in Washington. Novelist Louisa May Alcott served at the Union Hospital in Georgetown. Poet Walt Whitman served as a hospital volunteer, and in 1865 would publish his famous poem "The Wound-Dresser."[7] The United States Sanitary Commission had a significant presence in Washington, as did the United States Christian Commission and other relief agencies. The Freedman's Hospital was established in 1862 to serve the needs of the growing population of freed slaves.[8]

As the war progressed, the overcrowding severely strained the city's water supply. The Army Corps of Engineers constructed a new aqueduct that brought 10,000 US gallons (38,000 l; 8,300 imp gal) of fresh water to the city each day. Police and fire protection were beefed up, and work resumed to complete the unfinished dome of the Capitol Building. However, for most of the war, Washington suffered from unpaved streets, poor sanitation and garbage collection, swarms of mosquitos facilitated by the dank canals and sewers, and poor ventilation in most public (and private) buildings.[9]

Important political and military prisoners were often housed in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, including accused spies Rose Greenhow and Belle Boyd, as well as partisan ranger John S. Mosby. One inmate, Henry Wirz, the commandant of the Andersonville Prison in Georgia was hanged in the yard of the prison shortly after the war for his cruelty and neglect toward the Union prisoners of war.[10]

Lincoln's assassination

On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the war, Lincoln was shot in Ford's Theater by John Wilkes Booth during the play Our American Cousin. The next morning, at 7:22 AM, President Lincoln died in the house across the street, the first American president to be assassinated. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton said, "Now he belongs to the ages" (or perhaps "angels"). The residents and visitors to the city experienced a wide array of reactions, from stunned disbelief to rage. Stanton immediately closed off most major roads and bridges, and the city was placed under martial law. Scores of residents and workers were questioned during the growing investigation, and a handful were detained or arrested on suspicion of having aided the assassins or for a perception they were withholding information.

Lincoln's body was displayed in the Capitol rotunda, and thousands of Washington residents, as well as throngs of visitors, stood in long queues for hours to glimpse the fallen president. Hotels and restaurants were filled to capacity, bringing an unexpected windfall to their owners. Following the identification and eventual arrest of the actual conspirators, the city was the site of the trial and execution of several of the assassins, and again, Washington was the center of the nation's media attention.

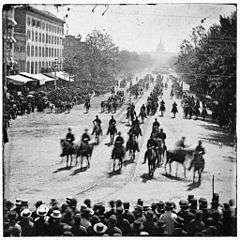

Grand Review of the Armies

On May 9, 1865, the new president, Andrew Johnson, declared that the rebellion was virtually at an end, and planned with government authorities a formal review to honor the victorious troops. One of his side goals was to change the mood of the capital, which was still in mourning following the assassination. Three of the leading Federal armies were close enough to travel to Washington to participate in the procession— the Army of the Potomac, the Army of the Tennessee, and the Army of Georgia. Officers in the three armies who had not seen each other for some time communed and renewed acquaintances, while at times, infantrymen engaged in verbal sparring (and sometimes fisticuffs) in the town's taverns and bars over which army was superior.

The Army of the Potomac was the first to parade through the city, on May 23, in a procession that stretched for seven miles. The mood in Washington was now one of gaiety and celebration, and the crowds and soldiers frequently engaged in singing patriotic songs as column passed the reviewing stand in front of the White House, where President Johnson, general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant, senior military leaders, the Cabinet, and leading government officials awaited.

On the following day, William T. Sherman led the 65,000 men of the Army of the Tennessee and the Army of Georgia along Washington's streets past the cheering crowds. Within a week after the celebrations, the two armies were disbanded and many of the volunteer regiments and batteries were sent home to be mustered out of the army.

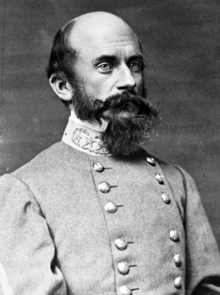

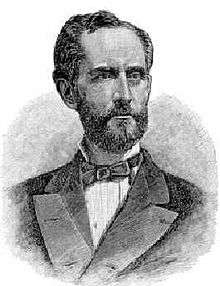

Notable Civil War leaders from Washington, D.C.

The District of Columbia, including Washington or adjoining Georgetown, was the birthplace of several Union army generals and naval admirals, as well as a leading Confederate commander.

-

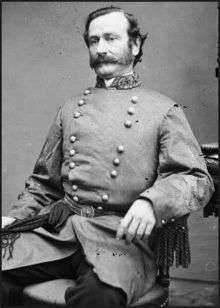

Lt. Gen.

Richard S. Ewell

CSA -

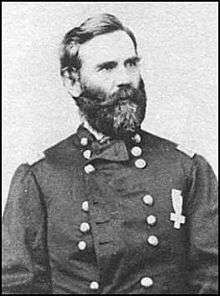

Maj. Gen.

Manning Force

USA -

Bvt. Maj. Gen.

George W. Getty

USA -

Admiral

Louis M. Goldsborough

USA -

Maj. Gen.

William Montrose Graham, Jr.

USA -

Maj. Gen.

Mansfield Lovell

CSA -

Maj. Gen.

Alfred Pleasonton

USA

Other important personalities of the Civil War born in the immediate Washington area included Confederate Senator Thomas Jenkins Semmes, Union general John Milton Brannan, John Rodgers Meigs (whose death sparked a significant controversy throughout the North), and Confederate brigade commander Richard Hanson Weightman.

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 Eicher, p. 843.

- ↑ Eicher, p.856.

- ↑ "History of D.C. Emancipation", District of Columbia Office of the Secretary

- 1 2 3 NPS description of defenses

- 1 2 Catton, p. 61.

- ↑ Wert, p. 80.

- ↑ Peck, Garrett (2015). Walt Whitman in Washington, D.C.: The Civil War and America's Great Poet. Charleston, SC: The History Press. pp. 15, 24, 73–80. ISBN 978-1626199736.

- ↑ Whitman's Drum Taps and Washington's Civil War hospitals

- ↑ WETA-TV, Explore DC: Civil War Washington website

- ↑ Old Capitol Prison

Notes

^[b] Data provided by "District of Columbia - Race and Hispanic Origin: 1800 to 1990" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 2002-09-13. Retrieved 2008-07-29. Until 1890, the U.S. Census Bureau counted the City of Washington, Georgetown, and unincorporated Washington County as three separate areas. The data provided in this article from before 1890 is calculated as if the District of Columbia were a single municipality as it is today. To view the population data for each specific area prior to 1890 see: Gibson, Campbell (June 1998). "Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States: 1790 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

References

- Catton, Bruce, Army of the Potomac: Mr. Lincoln's Army, Doubleday and Company, 1961

- Eicher, John H., and Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Furgurson, Ernest B., Freedom Rising : Washington In The Civil War, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004. ISBN 978-0-375-40454-2.

- NPS description of defenses

- Wert, Jeffry D., General James Longstreet: The Confederacy's Most Controversial Soldier: A Biography, Simon & Schuster, 1993, ISBN 0-671-70921-6.

External links

- Washington, D.C. defenses, National Park Service

- Civil War Washington

- C-SPAN American History TV Tour of Civil War Defenses of Washington, D.C.

Further reading

- Laas, Virginia Jeans, ed., Wartime Washington : The Civil War Letters of Elizabeth Blair Lee, University of Illinois Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-252-06859-1.

- Leech, Margaret, Reveille in Washington: 1860–1865, Harper and Brothers, 1941. ISBN 978-1-931313-23-0

- Leepson, Marc, Desperate Engagement: How a Little-Known Civil War Battle Saved Washington, D.C., and Changed The Course Of American History, Thomas Dunne Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0-312-36364-2.

| ||||||||||||||