Neutropenia

| Neutropenia | |

|---|---|

|

Blood film with a striking absence of neutrophils, leaving only red blood cells and platelets | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| ICD-10 | D70 |

| ICD-9-CM | 288.0 |

| DiseasesDB | 8994 |

| MedlinePlus | 007230 |

| eMedicine | med/1640 |

| MeSH | D009503 |

Neutropenia or neutropaenia, is an abnormally low concentration of neutrophils (a type of white blood cell) in the blood.[1] Neutrophils make up the majority of circulating white blood cells and serve as the primary defense against infections by destroying bacteria, bacterial fragments and immunoglobulin-bound viruses in the blood.[2] Patients with neutropenia are more susceptible to bacterial infections and, without prompt medical attention, the condition may become life-threatening (neutropenic sepsis).[3]

Neutropenia can be acute (temporary) or chronic (long lasting). The term is sometimes used interchangeably with "leukopenia" ("deficit in the number of white blood cells")[4]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms and signs of neutropenia are consistent with: fever, odynophagia, gingival pain, skin abscesses, and otitis. These symptoms may exist because individuals with neutropenia often have infection[5] Children may show signs of irritability, and poor feeding.[6] Hypotension has also been observed.[3]

Causes

The causes of neutropenia can be divided between problems that are transient and those that are chronic . Causes can be divided into these groups:[7]

- Chronic neutropenia:

- Transient neutropenia:

Gram-positive bacteria are present in 60-70% of bacterial infections. There are serious concerns regarding antibiotic-resistant organisms. These would include as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) or vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE).[9]

Other causes of congental neutropenia are Shwachman-Diamond syndrome, Cyclic neutropenia, Bone Marrow Failure Syndromes, Cartilage-hair hypoplasia, Reticular dysgenesis, and Barth syndrome. Viruses that infect of neutrophil progenitors can also be the cause of neutropenia. Viruses identified that have an effect on neutrophils are rubella and cytomegalovirus.[8]

Though the body can manufacture a normal level of neutrophils, in some cases the destruction of excessive numbers of neutriphils can lead to neutropenia. These are:

- Bacterial or fungal sepsis

- Necrotizing enterocolitis, circulating neutrophil population depleted due to migration into the intestines and peritoneum

- Alloimmune neonatal neutropenia, the mother produces antibodies against fetal neutrophils

- Inherited autoimmune neutropenia, mother has autoimmune neutropenia

- Autoimmune neutropenia of infancy, the sensitization to self-antigens[8]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of neutropenia can be divided into congenital and acquired. In congenital neutropenia (cyclic neutropenia) is autosomal dominant, mutations in the ELA2 gene ( neutrophil elastase), is the genetic reason for this condition. Acquired neutropenia (immune-associated neutropenia) is due to anti-neutrophil antibodies that work against neutrophil-specific antigens, ultimately altering neutrophil function.[10]

Neutropenia fever can complicate the treatment of cancers. Observations of pediatric patients have noted that fungal infections are more likely to develop in patients with neutropenia. Mortality increases during cancer treatments if neutropenia is also present.[3] Congenital neutropenia is determined by blood neutrophil counts (absolute neutrophil counts or ANC) < 0.5 × 109/L and recurrent bacterial infections beginning very early in childhood.[11]

Congenital neutropenia is related to alloimmunization, sepsis, maternal hypertension, twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome, and Rh hemolytic disease.[8]

Diagnosis

Neutropenia that is developed in response to chemotherapy typically becomes evident in seven to fourteen days after treatment. Conditions that indicate the presence of neutropenic fever are implanted devices; leukemia induction; the compromise of mucosal, mucociliary and cutaneous barriers; a rapid decline in absolute neutrophil count, duration of neutropenia >7-10 days, and other illnesses that exist in the patient.[9]

Signs of infection in patients can be subtle. Fevers are a common and early observation. Sometimes overlooked is the presence of hypothermia which can be present in sepsis. Physical examination and accessing the history and physical examination is focussed on sites of infection. Indwelling line sites, areas of skin breakdown, sinuses, nasopharynx, bronchi and lungs, alimentary tract, and skin are assessed.[9]

The diagnosis of neutropenia is done via the low neutrophil count detection on a full blood count. Generally, other investigations are required to arrive at the right diagnosis. When the diagnosis is uncertain, or serious causes are suspected, bone marrow biopsy may be necessary.Other investigations commonly performed: serial neutrophil counts for suspected cyclic neutropenia, tests for antineutrophil antibodies, autoantibody screen (and investigations for systemic lupus erythematosus), vitamin B12 and folate assays.[12][13] Rectal examinations are usually not performed due to the increased risk of introducing bacteria into the blood stream and the possible development of rectal abscesses. A routine chest X-ray and urinalysis may be can not be relied upon or considered normal due to the absence of neutrophils.[9]

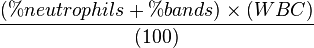

Classification

Generally accepted reference range for absolute neutrophil count (ANC) in adults is 1500 to 8000 cells per microliter (µl) of blood. Three general guidelines are used to classify the severity of neutropenia based on the ANC (expressed below in cells/µl):[14]

- Mild neutropenia (1000 ≥ ANC < 1500): minimal risk of infection

- Moderate neutropenia (500 ≥ ANC < 1000): moderate risk of infection

- Severe neutropenia (ANC < 500): severe risk of infection.

Each of these are either derived from laboratory tests or via the formula below:

Epidemiology

Neutropenia is usually detected shortly after birth, affecting 6% to 8% of all newborns in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs). Out of the approximately 600,000 neonates annually treated in NICUs in the United States, 48,000 may be diagnosed as neutropenic. Incidence of neutropinia is greater in premature infants. Six to fifty-eight percent of preterm neonates are diagnosed with this auto-immune disease. The incidence of neutropenia correlates with decreasing birth weight. The disorder is seen up to 38% in infants that weigh less than 1000g, 13% in infants weighing less than 2500g, and 3% of term infants weighing more than 2500 g. Neutropenia is often temporary, affecting most newborns in only first few days after birth. In others, it becomes more severe and chronic indicating a deficiency in innate immunity.[8]

Treatment

In terms of treatment for neutropenia recombinant granulocyte-colony stimulating factor, such as filgrastim[16] can be effective in patients with congenital forms of neutropenia including severe congenital neutropenia and cyclic neutropenia,[17] the amount needed (dosage) varies considerably (depending on the individual's condition) to stabilize the neutrophil count.[18] Guidelines for neutropenia regarding diet are currently being studied.[19]

Most cases of neonatal neutropenia are temporary. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended because of the possibility of encouraging the development of multidrug-resistant bacterial strains.[8]

Neutropenia can be treated with hematopoietic Growth Factors, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) or granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). These are cytokines (inflammation-inducing chemicals) that are present naturally in the body. These factors are used regularly in cancer treatment with adults and children. The factors promote neutrophil recovery following anticancer therapy.[8]

The administration of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs) has had some success in treating neutropenias of alloimmune and autoimmune origins with a response rate of about 50%. Blood transfusions have not been effective.[8]

Prognosis

If left untreated, patients with fever and absolute neutrophil count <500 have a mortality of up to 70% within 24 hours.[9] The prognosis of neutropenia depends on the cause. Antibiotic agents have improved the prognosis for individuals with severe neutropenia. Neutropenic fever in individuals treated for cancer has a mortality of 4-30%.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Neutropenia - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Information, National Center for Biotechnology; Pike, U. S. National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville; MD, Bethesda; Usa, 20894. "Neutrophils - National Library of Medicine". PubMed Health. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- 1 2 3 Fredricks, David N; Fung, Monica; Kim, Jane; Marty, Francisco M.; Schwarzinger, Michaël; Koo, Sophia (2015). "Meta-Analysis and Cost Comparison of Empirical versus Pre-Emptive Antifungal Strategies in Hematologic Malignancy Patients with High-Risk Febrile Neutropenia". PLOS ONE 10 (11): e0140930. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0140930. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ↑ Boxer, Laurence A. (2012-12-08). "How to approach neutropenia". ASH Education Program Book 2012 (1): 174–182. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2012.1.174. ISSN 1520-4391. PMID 23233578.

- ↑ "Neutropenia Clinical Presentation: History, Physical Examination". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Hazinski, Mary Fran (2012-05-04). Nursing Care of the Critically Ill Child. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 835. ISBN 0323086039.

- ↑ Newburger, Peter E.; Dale, David C. (2013-07-01). "Evaluation and Management of Patients with Isolated Neutropenia". Seminars in hematology 50 (3): 198–206. doi:10.1053/j.seminhematol.2013.06.010. ISSN 0037-1963. PMC 3748385. PMID 23953336.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ohls, Robin (2012). Hematology, immunology and infectious disease neonatology questions and controversies. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-2662-6: Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

- 1 2 3 4 5 Williams, Mark (2007). Comprehensive hospital medicine an evidence based approach. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-0223-9; Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

- ↑ Schwartzberg, Lee S. (2006-01-01). "Neutropenia: etiology and pathogenesis". Clinical Cornerstone. 8 Suppl 5: S5–11. ISSN 1098-3597. PMID 17379162. – via ScienceDirect (Subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries.)

- ↑ Makaryan, Vahagn; Rosenthal, Elisabeth A.; Bolyard, Audrey Anna; Kelley, Merideth L.; Below, Jennifer E.; Bamshad, Michael J.; Bofferding, Kathryn M.; Smith, Joshua D.; Buckingham, Kati; Boxer, Laurence A.; Skokowa, Julia; Welte, Karl; Nickerson, Deborah A.; Jarvik, Gail P.; Dale, David C. (2014). "TCIRG1-Associated Congenital Neutropenia". Human Mutation 35 (7): 824–827. doi:10.1002/humu.22563. ISSN 1059-7794.

- ↑ Levene, Malcolm I.; Lewis, S. M.; Bain, Barbara J.; Imelda Bates (2001). Dacie & Lewis Practical Haematology. London: W B Saunders. p. 586. ISBN 0-443-06377-X.

- ↑ "Neutropenic Patients and Neutropenic Regimes | Patient". Patient. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- 1 2 Hsieh MM, Everhart JE, Byrd-Holt DD, Tisdale JF, Rodgers GP (April 2007). "Prevalence of neutropenia in the U.S. population: age, sex, smoking status, and ethnic differences". Ann. Intern. Med. 146 (7): 486–92. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00004. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 17404350.

- ↑ "Absolute Neutrophil Count Calculator". reference.medscape.com. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ↑ Schouten, H. C. (3 October 2006). "Neutropenia management" (PDF). Annals of Oncology 17 (suppl 10): x85–x89. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdl243. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ James, R M; Kinsey, S E (2006-10-01). "The investigation and management of chronic neutropenia in children". Archives of Disease in Childhood 91 (10): 852–858. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.094706. ISSN 0003-9888. PMC 2066017. PMID 16990357.

- ↑ Agranulocytosis—Advances in Research and Treatment: 2012 Edition: ScholarlyBrief. ScholarlyEditions. 2012-12-26. p. 95. ISBN 9781481602754.

- ↑ Jubelirer, S. J. (6 April 2011). "The Benefit of the Neutropenic Diet: Fact or Fiction?". The Oncologist 16 (5): 704–707. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0001. PMC 3228185. PMID 21471277.

- ↑ "Neutropenia". eMedicine. MedScape. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

Further reading

- Vidal, Liat; Ben dor, Itsik; Paul, Mical; Eliakim-Raz, Noa; Pokroy, Ellisheva; Soares-Weiser, Karla; Leibovici, Leonard (2013-10-09). Oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment for febrile neutropenia in cancer patients. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd003992.pub3/full. ISBN 1465-1858.

- Turgeon, Mary Louise (2005-01-01). Clinical Hematology: Theory and Procedures. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781750073.

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||