Christoffel symbols

In mathematics and physics, the Christoffel symbols are an array of numbers describing an affine connection.[1] In other words, when a surface or other manifold is endowed with a sense of differential geometry — parallel transport, covariant derivatives, geodesics, etc. — the Christoffel symbols are a concrete representation of that geometry in coordinates on that surface or manifold. Frequently, but not always, the connection in question is the Levi-Civita connection of a metric tensor.

At each point of the underlying n-dimensional manifold, for any local coordinate system around that point, the Christoffel symbols are denoted Γijk for i, j, k = 1, 2, ..., n. Each entry of this n × n × n array is a real number. Under linear coordinate transformations on the manifold, the Christoffel symbols transform like the components of a tensor, but under general coordinate transformations they do not.

Christoffel symbols are used for performing practical calculations. For example, the Riemann curvature tensor can be expressed entirely in terms of the Christoffel symbols and their first partial derivatives. In general relativity, the connection plays the role of the gravitational force field with the corresponding gravitational potential being the metric tensor. When the coordinate system and the metric tensor share some symmetry, many of the Γijk are zero.

The Christoffel symbols are named for Elwin Bruno Christoffel (1829–1900).[2]

Preliminaries

The definitions given below are valid for both Riemannian manifolds and pseudo-Riemannian manifolds, such as those of general relativity, with careful distinction being made between upper and lower indices (contra-variant and co-variant indices). The formulas hold for either sign convention, unless otherwise noted. Einstein summation convention is used in this article. The connection coefficients of the Levi-Civita connection (or pseudo-Riemannian connection) expressed in a coordinate basis are called the Christoffel symbols.

Definition

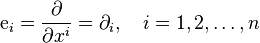

Given a local coordinate system xi, i = 1, 2, ..., n on a n-manifold M with metric tensor  , the tangent vectors

, the tangent vectors

define a local coordinate basis of the tangent space to M at each point of its domain.

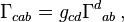

Christoffel symbols of the first kind

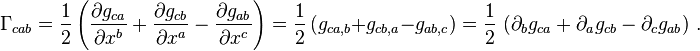

The Christoffel symbols of the first kind can be derived either from the Christoffel symbols of the second kind and the metric,[3]

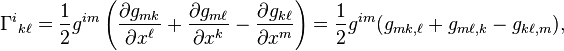

or from the metric alone,[3]

As an alternative notation one also finds[2][4][5]

It is worth noting that ![[ab, c] = [ba, c]](../I/m/91c2ff722579d646800cc0ca6fd85289.png) .[6]

.[6]

Christoffel symbols of the second kind (symmetric definition)

The Christoffel symbols of the second kind are the connection coefficients—in a coordinate basis—of the Levi-Civita connection, and since this connection has zero torsion, then in this basis the connection coefficients are symmetric, i.e.,  .[4] For this reason a torsion-free connection is often called 'symmetric'.

.[4] For this reason a torsion-free connection is often called 'symmetric'.

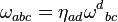

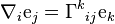

In other words, the Christoffel symbols of the second kind[7][4]

(sometimes

(sometimes  or

or  )[2][4] are defined as the unique coefficients such that the equation

)[2][4] are defined as the unique coefficients such that the equation

holds, where  is the Levi-Civita connection on M taken in the coordinate direction

is the Levi-Civita connection on M taken in the coordinate direction  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  and where

and where  is a local coordinate (holonomic) basis.

is a local coordinate (holonomic) basis.

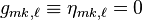

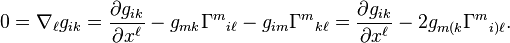

The Christoffel symbols can be derived from the vanishing of the covariant derivative of the metric tensor  :

:

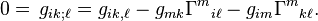

As a shorthand notation, the nabla symbol and the partial derivative symbols are frequently dropped, and instead a semi-colon and a comma are used to set off the index that is being used for the derivative. Thus, the above is sometimes written as

Using that the symbols are symmetric in the lower two indices, one can solve explicitly for the Christoffel symbols as a function of the metric tensor by permuting the indices and resumming:[6]

where  is the inverse of the matrix

is the inverse of the matrix  , defined as (using the Kronecker delta, and Einstein notation for summation)

, defined as (using the Kronecker delta, and Einstein notation for summation)

.

Although the Christoffel symbols are written in the same notation as tensors with index notation, they are not tensors,[8]

since they do not transform like tensors under a change of coordinates; see below.

.

Although the Christoffel symbols are written in the same notation as tensors with index notation, they are not tensors,[8]

since they do not transform like tensors under a change of coordinates; see below.

Connection coefficients in a non holonomic basis

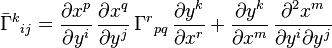

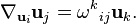

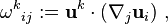

The Christoffel symbols are most typically defined in a coordinate basis, which is the convention followed here. In other words, the name Christoffel symbols is reserved only for coordinate (i.e., holonomic) frames. However, the connection coefficients can also be defined in an arbitrary (i.e., non holonomic) basis of tangent vectors  by

by

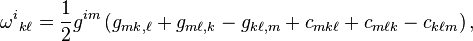

Explicitly, in terms of the metric tensor, this is[7]

where  are the commutation coefficients of the basis; that is,

are the commutation coefficients of the basis; that is,

where  are the basis vectors and

are the basis vectors and ![[{\,},{\,}]\](../I/m/ef84cbdd256f01ff599aebe273706962.png) is the Lie bracket. The standard unit vectors in spherical and cylindrical coordinates furnish an example of a basis with non-vanishing commutation coefficients.

is the Lie bracket. The standard unit vectors in spherical and cylindrical coordinates furnish an example of a basis with non-vanishing commutation coefficients.

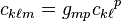

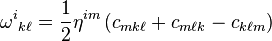

Ricci rotation coefficients (asymmetric definition)

When we choose the basis  orthonormal:

orthonormal:  then

then  . This implies that

. This implies that

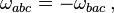

and the connection coefficients become antisymmetric in the first two indices:

where  .

.

In this case, the connection coefficients  are called the Ricci rotation coefficients.[9][10]

are called the Ricci rotation coefficients.[9][10]

Equivalently, one can define Ricci rotation coefficients as follows:[7]

where  is an orthonormal non holonomic basis

and

is an orthonormal non holonomic basis

and  its co-basis.

its co-basis.

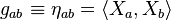

Relationship to index-free notation

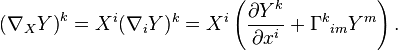

Let X and Y be vector fields with components  and

and  . Then the kth component of the covariant derivative of Y with respect to X is given by

. Then the kth component of the covariant derivative of Y with respect to X is given by

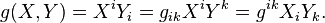

Here, the Einstein notation is used, so repeated indices indicate summation over indices and contraction with the metric tensor serves to raise and lower indices:

Keep in mind that  and that

and that  , the Kronecker delta. The convention is that the metric tensor is the one with the lower indices; the correct way to obtain

, the Kronecker delta. The convention is that the metric tensor is the one with the lower indices; the correct way to obtain  from

from  is to solve the linear equations

is to solve the linear equations  .

.

The statement that the connection is torsion-free, namely that

is equivalent to the statement that—in a coordinate basis—the Christoffel symbol is symmetric in the lower two indices:

The index-less transformation properties of a tensor are given by pullbacks for covariant indices, and pushforwards for contravariant indices. The article on covariant derivatives provides additional discussion of the correspondence between index-free notation and indexed notation.

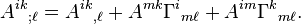

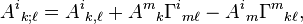

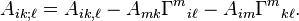

Covariant derivatives of tensors

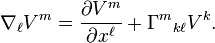

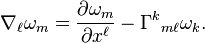

The covariant derivative of a vector field Vm is

The covariant derivative of a scalar field  is just

is just

and the covariant derivative of a covector field  is

is

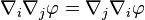

The symmetry of the Christoffel symbol now implies

for any scalar field, but in general the covariant derivatives of higher order tensor fields do not commute (see curvature tensor).

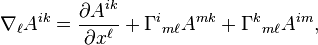

The covariant derivative of a type (2,0) tensor field  is

is

that is,

If the tensor field is mixed then its covariant derivative is

and if the tensor field is of type (0,2) then its covariant derivative is

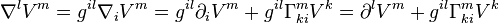

Contravariant derivatives of tensors

To find the contravariant derivative of a vector field, we must first transform it into a covariant derivative using the metric tensor

Change of variable

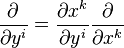

Under a change of variable from  to

to  , vectors transform as

, vectors transform as

and so

where the overline denotes the Christoffel symbols in the y coordinate system. Note that the Christoffel symbol does not transform as a tensor, but rather as an object in the jet bundle. More precisely, the Christoffel symbols can be considered as functions on the jet bundle of the frame bundle of M, independent of any local coordinate system. Choosing a local coordinate system determines a local section of this bundle, which can then be used to pull back the Christoffel symbols to functions on M, though of course these functions then depend on the choice of local coordinate system.

At each point, there exist coordinate systems in which the Christoffel symbols vanish at the point.[11] These are called (geodesic) normal coordinates, and are often used in Riemannian geometry.

Applications to general relativity

The Christoffel symbols find frequent use in Einstein's theory of general relativity, where spacetime is represented by a curved 4-dimensional Lorentz manifold with a Levi-Civita connection. The Einstein field equations—which determine the geometry of spacetime in the presence of matter—contain the Ricci tensor, and so calculating the Christoffel symbols is essential. Once the geometry is determined, the paths of particles and light beams are calculated by solving the geodesic equations in which the Christoffel symbols explicitly appear.

See also

- Basic introduction to the mathematics of curved spacetime

- Proofs involving Christoffel symbols

- Differentiable manifold

- List of formulas in Riemannian geometry

- Ricci calculus

- Riemann–Christoffel tensor

- Gauss–Codazzi equations

- Example computation of Christoffel symbols

Notes

- ↑ See, for instance, (Spivak 1999) and (Choquet-Bruhat & DeWitt-Morette 1977)

- 1 2 3 Christoffel, E.B. (1869), "Ueber die Transformation der homogenen Differentialausdrücke zweiten Grades", Jour. für die reine und angewandte Mathematik, B. 70: 46–70

- 1 2 Ludvigsen, Malcolm (1999), General Relativity: A Geometrical Approach, p. 88

- 1 2 3 4 Chatterjee, U.; Chatterjee, N. (2010). Vector and Tensor Analysis. p. 480.

- ↑ Struik, D.J. (1961). Lectures on Classical Differential Geometry (first published in 1988 Dover ed.). p. 114.

- 1 2 Bishop, R.L.; Goldberg (1968), Tensor Analysis on Manifolds, p. 241

- 1 2 3 http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ChristoffelSymboloftheSecondKind.html.

- ↑ See, for example, (Kreyszig 1991), page 141

- ↑ G. Ricci-Curbastro (1896). "Dei sistemi di congruenze ortogonali in una varietà qualunque". Mem. Acc. Lincei 2 (5): 276–322.

- ↑ H. Levy (1925). "Ricci's coefficients of rotation". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 31 (3-4): 142–145. doi:10.1090/s0002-9904-1925-03996-8.

- ↑ This is assuming that the connection is symmetric (e.g., the Levi-Civita connection). If the connection has torsion, then only the symmetric part of the Christoffel symbol can be made to vanish.

References

- Abraham, Ralph; Marsden, Jerrold E. (1978), Foundations of Mechanics, London: Benjamin/Cummings Publishing, pp. See chapter 2, paragraph 2.7.1, ISBN 0-8053-0102-X

- Bishop, R.L.; Goldberg, S.I. (1968), Tensor Analysis on Manifolds (First Dover 1980 ed.), The Macmillan Company, ISBN 0-486-64039-6

- Choquet-Bruhat, Yvonne; DeWitt-Morette, Cécile (1977), Analysis, Manifolds and Physics, Amsterdam: Elsevier, ISBN 978-0-7204-0494-4

- Landau, Lev Davidovich; Lifshitz, Evgeny Mikhailovich (1951), The Classical Theory of Fields, Course of Theoretical Physics, Volume 2 (Fourth Revised English ed.), Oxford: Pergamon Press, pp. See chapter 10, paragraphs 85, 86 and 87, ISBN 0-08-025072-6

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1991), Differential Geometry, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-66721-8

- Misner, Charles W.; Thorne, Kip S.; Wheeler, John Archibald (1970), Gravitation, New York: W.H. Freeman, pp. See chapter 8, paragraph 8.5, ISBN 0-7167-0344-0

- Ludvigsen, Malcolm (1999), General Relativity: A Geometrical Approach, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-63019-3

- Spivak, Michael (1999), A Comprehensive introduction to differential geometry, Volume 2, Publish or Perish, ISBN 0-914098-71-3

- Chatterjee, U.; Chatterjee, N. (2010). Vector & Tensor Analysis. Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-93-8059-905-2.

- Struik, D.J. (1961). Lectures on Classical Differential Geometry (first published in 1988 Dover ed.). Dover. ISBN 0-486-65609-8.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![\Gamma_{cab} = [ab, c].](../I/m/68c31a7272be8d86f7c9a1ac2dfc3c4e.png)

![[\mathbf{u}_k,\mathbf{u}_\ell] = c_{k\ell}{}^m \mathbf{u}_m\,\](../I/m/a3c2353fe4bd78510ba3c5057729b278.png)

![\nabla_X Y - \nabla_Y X = [X,Y]\](../I/m/d648cf4c00e22c528c0c716bfc400b2d.png)