Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis

| Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| OMIM | 211600 601847 602347 |

| DiseasesDB | 29084 |

| eMedicine | ped/2771 |

| GeneReviews | |

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) refers to a group of familial cholestatic conditions caused by defects in biliary epithelial transporters. The clinical presentation usually occurs first in childhood with progressive cholestasis. This usually leads to failure to thrive, cirrhosis, and the need for liver transplantation.

Signs and symptoms

The onset of the disease is usually before age 2, but patients have been diagnosed with PFIC even into adolescence. Of the three entities, PFIC-3 usually presents earliest. Patients usually present in early childhood with cholestasis, jaundice, and failure to thrive. Intense pruritus is characteristic;[1] in patients who present in adolescence, it has been linked with suicide. Patients may have fat malabsorption, leading to fat soluble vitamin deficiency, and complications, including osteopenia.[2]

Pathogenesis

PFIC-1 is caused by a variety of mutations in ATP8B1, a gene coding for a P-type ATPase protein, FIC-1, that is responsible for phospholipid translocation across membranes.[3] It was previously identified as clinical entities known as Byler's disease and Greenland-Eskimo familial cholestasis. Patients with PFIC-1 may also have watery diarrhea, in addition to the clinical features below, due to FIC-1's expression in the intestine. How ATP8B1 mutation leads to cholestasis is not yet well understood.

PFIC-2 is caused by a variety of mutations in ABCB11, the gene that codes for the bile salt export pump, or BSEP. Retention of bile salts within hepatocytes, which are the only cell type to express BSEP, causes hepatocellular damage and cholestasis.

PFIC-3 is caused by a variety of mutations in ABCB4, the gene encoding multidrug resistance protein 3 (MDR3),[4] which codes for a floppase responsible for phosphatidylcholine translocation. The defective phosphatidylcholine translocation leads to a lack of phosphatidylcholine in bile. Phosphatidylcholine normally chaperones bile acids, preventing damage to the biliary epithelium. The free or "unchaperoned" bile acids in bile of patients with MDR3 deficiency cause a cholangitis. Biochemically, this is of note, as PFIC-3 is associated with a markedly elevated GGT.

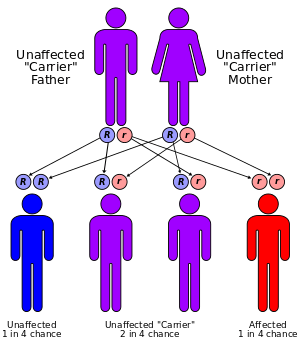

The inheritance pattern of all three forms of PFIC defined to date is autosomal recessive.

Liver biopsies typically show evidence of cholestasis (including bile plugs and bile infarcts), duct hypoplasia, hepatocellular injury, and Zone 3 fibrosis. Giant cell change and other features of hepatocellular injury are more pronounced in PFIC-2 than in PFIC-1 or PFIC-3. End-stage disease in all forms of PFIC defined to date is characterized by bridging fibrosis with duct proliferation in peri-portal regions.[5]

Diagnosis

Biochemical markers include a normal GGT for PFIC-1 and -2, with a markedly elevated GGT for PFIC-3. Serum bile acid levels are grossly elevated. Serum cholesterol levels are typically not elevated, as is seen usually in cholestasis, as the pathology is due to a transporter as opposed to an anatomical problem with biliary cells.

Treatment

Initial treatment is supportive, with the use of agents to treat cholestasis and pruritus, including the following:

- Ursodeoxycholic acid

- Cholestyramine

- Rifampin

- Naloxone, in refractory cases

Patients should be supplemented with fat-soluble vitamins, and occasionally medium-chain triglycerides in order to improve growth.

When liver synthetic dysfunction is significant, patients should be listed for transplantation. Family members should be tested for PFIC mutations, in order to determine risk of transmission.

Prognosis

The disease is typically progressive, leading to fulminant liver failure and death in childhood, in the absence of liver transplantation. Hepatocellular carcinoma may develop in PFIC-2 at a very early age; even toddlers have been affected.

Epidemiology

- Consanguinity is believed to be a major risk factor.

- Similar transport protein mutations are believed to pose a higher risk for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy.

See also

References

- ↑ Shneider BL (2004). "Progressive intrahepatic cholestasis: mechanisms, diagnosis and therapy". Pediatric transplantation 8 (6): 609–12. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3046.2004.00240.x. PMID 15598335.

- ↑ "eMedicine - Progressive Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis : Article by Karan M Emerick, MD". Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ↑ Bull LN, van Eijk MJ, Pawlikowska L, et al. (1998). "A gene encoding a P-type ATPase mutated in two forms of hereditary cholestasis". Nat. Genet. 18 (3): 219–24. doi:10.1038/ng0398-219. PMID 9500542.

- ↑ Jacquemin E, De Vree JM, Cresteil D, et al. (2001). "The wide spectrum of multidrug resistance 3 deficiency: from neonatal cholestasis to cirrhosis of adulthood". Gastroenterology 120 (6): 1448–58. doi:10.1053/gast.2001.23984. PMID 11313315.

- ↑ Alonso EM, Snover DC, Montag A, Freese DK, Whitington PF (1994). "Histologic pathology of the liver in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis". J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 18 (2): 128–33. doi:10.1097/00005176-199402000-00002. PMID 8014759.

External links

- Patient pamphlet

- GeneReview/NIH/UW entry on Low γ-GT Familial Intrahepatic Cholestasis

- OMIM entry on CHOLESTASIS, PROGRESSIVE FAMILIAL INTRAHEPATIC, 1; PFIC1

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||