Chiller

A chiller is a machine that removes heat from a liquid via a vapor-compression or absorption refrigeration cycle. This liquid can then be circulated through a heat exchanger to cool air or equipment as required. As a necessary byproduct, refrigeration creates waste heat that must be exhausted to ambient or, for greater efficiency, recovered for heating purposes. Concerns in design and selection of chillers include performance, efficiency, maintenance, and product life cycle environmental impact

Use in air conditioning

In air conditioning systems, chilled water is typically distributed to heat exchangers, or coils, in air handling units or other types of terminal devices which cool the air in their respective space(s), and then the water is re-circulated back to the chiller to be cooled again. These cooling coils transfer sensible heat and latent heat from the air to the chilled water, thus cooling and usually dehumidifying the air stream. A typical chiller for air conditioning applications is rated between 15 and 150 short tons (13 and 134 long tons; 14 and 136 t) (180,000 to 18,000,000 BTU/h or 53 to 5,275 kW), and at least one manufacturer can produce chillers capable of up to 8,500 tons of cooling.[1] Chilled water temperatures can range from 35 to 45 °F (2 to 7 °C), depending upon application requirements.[2]

When the chillers for the air conditioning systems are not operable or they are in need of a repair or replacement, emergency chillers may be used to supply chilled water. Rental chillers are mounted on a trailer so that they can be quickly deployed to the site. Large chilled water hoses are used to connect between the rental chillers and the air conditioning systems.[3]

Use in industry

In industrial application, chilled water or other liquid from the chiller is pumped through process or laboratory equipment. Industrial chillers are used for controlled cooling of products, mechanisms and factory machinery in a wide range of industries. They are often used in the plastic industries, injection and blow molding, metal working cutting oils, welding equipment, die-casting and machine tooling, chemical processing, pharmaceutical formulation, food and beverage processing, paper and cement processing, vacuum systems, X-ray diffraction, power supplies and power generation stations, analytical equipment, semiconductors, compressed air and gas cooling. They are also used to cool high-heat specialized items such as MRI machines and lasers, and in hospitals, hotels and campuses.

Chillers for industrial applications can be centralized, where a single chiller serves multiple cooling needs, or decentralized where each application or machine has its own chiller. Each approach has its advantages. It is also possible to have a combination of both centralized and decentralized chillers, especially if the cooling requirements are the same for some applications or points of use, but not all.

Decentralized chillers are usually small in size and cooling capacity, usually from 0.2 to 10 short tons (0.179 to 8.929 long tons; 0.181 to 9.072 t). Centralized chillers generally have capacities ranging from ten tons to hundreds or thousands of tons.

Chilled water is used to cool and dehumidify air in mid- to large-size commercial, industrial, and institutional (CII) facilities. Water chillers can be water-cooled, air-cooled, or evaporatively cooled. Water-cooled chillers incorporate the use of cooling towers which improve the chillers' thermodynamic effectiveness as compared to air-cooled chillers. This is due to heat rejection at or near the air's wet-bulb temperature rather than the higher, sometimes much higher, dry-bulb temperature. Evaporatively cooled chillers offer higher efficiencies than air-cooled chillers but lower than water-cooled chillers.

Water-cooled chillers are typically intended for indoor installation and operation, and are cooled by a separate condenser water loop and connected to outdoor cooling towers to expel heat to the atmosphere.

Air-cooled and evaporatively cooled chillers are intended for outdoor installation and operation. Air-cooled machines are directly cooled by ambient air being mechanically circulated directly through the machine's condenser coil to expel heat to the atmosphere. Evaporatively cooled machines are similar, except they implement a mist of water over the condenser coil to aid in condenser cooling, making the machine more efficient than a traditional air-cooled machine. No remote cooling tower is typically required with either of these types of packaged air-cooled or evaporatively cooled chillers.

Where available, cold water readily available in nearby water bodies might be used directly for cooling, place or supplement cooling towers. The Deep Lake Water Cooling System in Toronto, Canada, is an example. It uses cold lake water to cool the chillers, which in turn are used to cool city buildings via a district cooling system. The return water is used to warm the city's drinking water supply, which is desirable in this cold climate. Whenever a chiller's heat rejection can be used for a productive purpose, in addition to the cooling function, very high thermal effectiveness is possible.

Vapor-compression chiller technology

There are four basic types of compressors used in vapor compression chillers: Reciprocating compression, scroll compression, screw-driven compression, and centrifugal compression are all mechanical machines that can be powered by electric motors, steam, or gas turbines. They produce their cooling effect via the "reverse-Rankine" cycle, also known as 'vapor-compression'. With evaporative cooling heat rejection, their coefficients-of-performance (COPs) are very high; typically 4.0 or more.

- COP

- COP

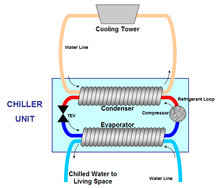

Current vapor-compression chiller technology is based on the "reverse-Rankine" cycle known as vapor-compression. See the attached diagram which outlines the key components of the chiller system.

Key components of the chiller:

Refrigeration Compressors - are essentially a pump for refrigerant gas. The capacity of the compressor, and hence the chiller cooling capacity is measured in kilowatts input (kW), Horse Power input (HP), or volumetric flow (m3/h, ft3/h). The mechanism for compressing refrigerant gas differs between compressors, and each has its own application. Common refrigeration compressors include Reciprocating, Scroll, Screw, or Centrifugal. These can be powered by electric motors, steam turbines or gas turbines. Compressors can have an integrated motor from a specific manufacturer, or be open drive - allowing the connection to another type of mechanical connection. Compressors can also be either Hermetic (welded closed) or semi-hermetic (bolted together).

In recent years, application of Variable Speed Drive (VSD) technology has increased efficiencies of vapor compression chillers. The first VSD was applied to centrifugal compressor chillers in the late 1970s and has become the norm as the cost of energy has increased. Now, VSDs are being applied to rotary screw and scroll technology compressors.

Condensers can be air cooled, water cooled, or evaporative. The condenser is a heat exchanger which allows heat to migrate from the refrigerant gas to either water or air. Air cooled condenser are manufactured from copper tubes (for the refrigerant flow) and aluminium fins (for the air flow). Each condenser has a different material cost and they vary in terms of efficiency. With evaporative cooling condensers, their coefficients-of-performance (COPs) are very high; typically 4.0 or more.

The expansion device or refrigerant metering device (RMD) restricts the flow of the liquid refrigerant causing a pressure drop that vaporizes some of the refrigerant; this vaporization absorbs heat from nearby liquid refrigerant. The RMD is located immediately prior to the evaporator so that the cold gas in the evaporator can absorb heat from the water in the evaporator. There is a sensor for the RMD on the evaporator outlet side which allows the RMD to regulate the refrigerant flow based on the chiller design requirement.

Evaporators can be plate type or shell and tube type. The evaporator is a heat exchanger which allows the heat energy to migrate from the water stream into the refrigerant gas. During the state change of the remaining liquid to gas, the refrigerant can absorb large amounts of heat without changing temperature.

How absorption technology works

The thermodynamic cycle of an absorption chiller is driven by a heat source; this heat is usually delivered to the chiller via steam, hot water, or combustion. Compared to electrically powered chillers, an absorption chiller has very low electrical power requirements - very rarely above 15 kW combined consumption for both the solution pump and the refrigerant pump. However, its heat input requirements are large, and its COP is often 0.5 (single-effect) to 1.0 (double-effect). For the same tonnage capacity, an absorption chiller requires a much larger cooling tower than a vapor-compression chiller. However, absorption chillers, from an energy-efficiency point of view, excel where cheap, high-grade heat or waste heat is readily available. In extremely sunny climates, solar energy has been used to operate absorption chillers.

The single-effect absorption cycle uses water as the refrigerant and lithium bromide as the absorbent. It is the strong affinity that these two substances have for one another that makes the cycle work. The entire process occurs in almost a complete vacuum.

- Solution Pump : A dilute lithium bromide solution (63% concentration) is collected in the bottom of the absorber shell. From here, a hermetic solution pump moves the solution through a shell and tube heat exchanger for preheating.

- Generator : After exiting the heat exchanger, the dilute solution moves into the upper shell. The solution surrounds a bundle of tubes which carries either steam or hot water. The steam or hot water transfers heat into the pool of dilute lithium bromide solution. The solution boils, sending refrigerant vapor upward into the condenser and leaving behind concentrated lithium bromide. The concentrated lithium bromide solution moves down to the heat exchanger, where it is cooled by the weak solution being pumped up to the generator.

- Condenser : The refrigerant vapor migrates through mist eliminators to the condenser tube bundle. The refrigerant vapor condenses on the tubes. The heat is removed by the cooling water which moves through the inside of the tubes. As the refrigerant condenses, it collects in a trough at the bottom of the condenser.

- Evaporator : The refrigerant liquid moves from the condenser in the upper shell down to the evaporator in the lower shell and is sprayed over the evaporator tube bundle. Due to the extreme vacuum of the lower shell [6 mm Hg (0.8 kPa) absolute pressure], the refrigerant liquid boils at approximately 39 °F (4 °C), creating the refrigerant effect. (This vacuum is created by hygroscopic action - the strong affinity lithium bromide has for water - in the Absorber directly below.)

- Absorber : As the refrigerant vapor migrates to the absorber from the evaporator, the strong lithium bromide solution from the generator is sprayed over the top of the absorber tube bundle. The strong lithium bromide solution actually pulls the refrigerant vapor into solution, creating the extreme vacuum in the evaporator. The absorption of the refrigerant vapor into the lithium bromide solution also generates heat which is removed by the cooling water. Now the dilute lithium bromide solution collects in the bottom of the lower shell, where it flows down to the solution pump. The chilling cycle is now completed and the process begins once again.[4]

Industrial chiller technology

Industrial chillers typically come as complete, packaged, closed-loop systems, including the chiller unit, condenser, and pump station with recirculating pump, expansion valve, no-flow shutdown, internal cold water control. The internal tank helps maintain cold water temperature and prevents temperature spikes from occurring. Closed-loop industrial chillers recirculate a clean coolant or clean water with condition additives at a constant temperature and pressure to increase the stability and reproducibility of water-cooled machines and instruments. The water flows from the chiller to the application's point of use and back.

If the water temperature differentials between inlet and outlet are high, then a large external water tank would be used to store the cold water. In this case the chilled water is not going directly from the chiller to the application, but goes to the external water tank which acts as a sort of "temperature buffer." The cold water tank is much larger than the internal water goes from the external tank to the application and the return hot water from the application goes back to the external tank, not to the chiller.

The less common open loop industrial chillers control the temperature of a liquid in an open tank or sump by constantly recirculating it. The liquid is drawn from the tank, pumped through the chiller and back to the tank. In industrial water chillers is the use of water cooling instead of air cooling. In this case the condenser does not cool the hot refrigerant with ambient air, but uses water that is cooled by a cooling tower. This development allows a reduction in energy requirements by more than 15% and also allows a significant reduction in the size of the chiller, due to the small surface area of the water-based condenser and the absence of fans. Additionally, the absence of fans allows for significantly reduced noise levels.

Most industrial chillers use refrigeration as the media for cooling, but some rely on simpler techniques such as air or water flowing over coils containing the coolant to regulate temperature. Water is the most commonly used coolant within process chillers, although coolant mixtures (mostly water with a coolant additive to enhance heat dissipation) are frequently employed.

Industrial chiller selection

Important specifications to consider when searching for industrial chillers include the total life cycle cost, the power source, chiller IP rating, chiller cooling capacity, evaporator capacity, evaporator material, evaporator type, condenser material, condenser capacity, ambient temperature, motor fan type, noise level, internal piping materials, number of compressors, type of compressor, number of fridge circuits, coolant requirements, fluid discharge temperature, and COP (the ratio between the cooling capacity in RT to the energy consumed by the whole chiller in KW). For medium to large chillers this should range from 3.5 to 7.0, with higher values meaning higher efficiency. Chiller efficiency is often specified in kilowatts per refrigeration ton (kW/RT).

Process pump specifications that are important to consider include the process flow, process pressure, pump material, elastomer and mechanical shaft seal material, motor voltage, motor electrical class, motor IP rating and pump rating. If the cold water temperature is lower than −5 °C, then a special pump needs to be used to be able to pump the high concentrations of ethylene glycol. Other important specifications include the internal water tank size and materials and full load current.

Control panel features that should be considered when selecting between industrial chillers include the local control panel, remote control panel, fault indicators, temperature indicators, and pressure indicators.

Additional features include emergency alarms, hot gas bypass, city water switchover, and casters.[4]

Demountable chillers are also an option for deployment in remote areas and where the conditions may be hot and dusty.[5]

Refrigerants

A vapor-compression chiller uses a refrigerant internally as its working fluid. Many refrigerants options are available; when selecting a chiller, the application cooling temperature requirements and refrigerant's cooling characteristics need to be matched. Important parameters to consider are the operating temperatures and pressures.

There are several environmental factors that concern refrigerants, and also affect the future availability for chiller applications. This is a key consideration in intermittent applications where a large chiller may last for 25 years or more. Ozone depletion potential (ODP) and global warming potential (GWP) of the refrigerant need to be considered. ODP and GWP data for some of the more common vapor-compression refrigerants (noting that many of these refrigerants are highly flammable and/or toxic):[6]

| Refrigerant | ODP | GWP |

|---|---|---|

| R12 | 1 | 2400 |

| R123 | 0.012 | 76 |

| R134a | 0 | 1300 |

| R22 | 0.05 | 1700 |

| R290 (propane) | 0 | 3 |

| R401a | 0.027 | 970 |

| R404a | 0 | 3260 |

| R407a | 0 | 2000 |

| R407c | 0 | 1525 |

| R408a | 0.016 | 3020 |

| R409a | 0.039 | 1290 |

| R410a | 0 | 1725 |

| R500 | 0.7 | ??? |

| R502 | 0.18 | 5600 |

| R600a | 0 | 3 |

| R744 (CO2)[7] | 0 | 1 |

| R717 (ammonia) | 0 | 0 |

| R718 (water)[8] | 0 | 0 |

R12 is the ODP reference. CO2 is the GWP reference

The refrigerants used in the chillers sold in Europe are mainly R410a (70%), R407c (20%) and R134a (10%).[9]

See also

References

- ↑ TITAN Multistage Industrial Chillers (FORM 160.72-EG1) (PDF). York International. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- ↑ American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers http://www.ashrae.org/publications/page/158

- ↑ Request for Proposal #946 - Emergency Chillers Rentals (PDF). Montclair State University. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- 1 2 http://matsu.com.au/chiller-range/chiller-range-2

- ↑ "Summit Matsu Chillers - Chillers for Mining - Summit Matsu Chillers". Summit Matsu Chillers.

- ↑ "Refrigerants". Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ "R744 (Carbon dioxide)". Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ↑ Kilicarslon, Ali; Müller, Norbert (18 July 2005). "A comparative study of water as a refrigerant with some current refrigerants" (PDF). Int. J. Energy Res. (Wiley) 29: 947–959. doi:10.1002/er.1084.

- ↑ Eurovent Market Intelligence https://www.eurovent-marketintelligence.eu/

External links

|