Children's literature

.jpg)

Children's literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are enjoyed by children. Modern children's literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader.

Children's literature can be traced to stories and songs, part of a wider oral tradition, that adults shared with children before publishing existed. The development of early children's literature, before printing was invented, is difficult to trace. Even after printing became widespread, many classic "children's" tales were originally created for adults and later adapted for a younger audience. Since the 15th century, a large quantity of literature, often with a moral or religious message, has been aimed specifically at children. The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries became known as the "Golden Age of Children's Literature" as this period included the publication of many books acknowledged today as classics.

Introduction

There is no single or widely used definition of children's literature.[1]:15–17 It can be broadly defined as anything that children read[2] or more specifically defined as fiction, non-fiction, poetry, or drama intended for and used by children and young people.[3][4]:xvii Nancy Anderson, of the College of Education at the University of South Florida, defines children's literature as "all books written for children, excluding works such as comic books, joke books, cartoon books, and non-fiction works that are not intended to be read from front to back, such as dictionaries, encyclopedias, and other reference materials".[5]

The International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature notes that "the boundaries of genre ... are not fixed but blurred".[1]:4 Sometimes, no agreement can be reached about whether a given work is best categorized as literature for adults or children. Some works defy easy categorization. J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series was written and marketed for young adults, but it is also popular among adults. The series' extreme popularity led The New York Times to create a separate best-seller list for children's books.[6]

Despite the widespread association of children's literature with picture books, spoken narratives existed before printing, and the root of many children's tales go back to ancient storytellers.[7]:30 Seth Lerer, in the opening of Children's Literature: A Reader's History from Aesop to Harry Potter, says, "This book presents a history of what children have heard and read ... The history I write of is a history of reception."[8]:2

History

Early children's literature consisted of spoken stories, songs, and poems that were used to educate, instruct, and entertain children.[9] It was only in the 18th century, with the development of the concept of childhood, that a separate genre of children's literature began to emerge, with its own divisions, expectations, and canon.[10]:x-xi

French historian Philippe Ariès argues in his 1962 book Centuries of Childhood that the modern concept of childhood only emerged in recent times. He explains that children were in the past not considered as greatly different from adults and were not given significantly different treatment.[11]:5 As evidence for this position, he notes that, apart from instructional and didactic texts for children written by clerics like the Venerable Bede and Ælfric of Eynsham, there was a lack of any genuine literature aimed specifically at children before the 18th century.[12][13]:11

Other scholars have qualified this viewpoint by noting that there was a literature designed to convey the values, attitudes, and information necessary for children within their cultures,[14] such as the Play of Daniel from the 12th century.[8]:46[15]:4 Pre-modern children's literature, therefore, tended to be of a didactic and moralistic nature, with the purpose of conveying conduct-related, educational and religious lessons.[15]:6–8

Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Every culture has its own mythology, unique fables, and other traditional stories that are told for instruction and entertainment.[1]:654 Early folk-type tales included the Panchatantra from India, which was composed about 200 AD and may be "the world's oldest collection of stories for children".[1]:807[7]:301 Oral stories that would have been enjoyed by children include the tale of The Asurik Tree, which dates back at least 3,000 years in Persia.[16]

In Imperial China, children attended public events with their parents, where they would listen to the complicated tales of professional storytellers. Children also watched the plays performed at festivals and fairs. Though not specifically intended for children, the elaborate costumes, acrobatics, and martial arts held even a young child's interest. The stories often explained the background behind the festival, covering folklore, history, and politics. Storytelling may have reached its peak during the Song Dynasty from 960-1279. This traditional literature was used for instruction in Chinese schools until the 20th century.[1]:830–831

Greek and Roman children would have enjoyed listening to stories such as the Odyssey, written by Homer, and Aesop's Fables by the eponymous Aesop.

Examples of medieval literature include Gesta Romanorum, the Roman fables of Avianus, the French Livre pour l'enseignement de ses filles, and the Welsh Mabinogion. In Ireland, many of the thousands of folk stories were recorded in the 11th and 12th centuries. Written in Old Irish on vellum, they began spreading through Europe, influencing other folk tales with stories of magic, witches, and fairies.[7]:256[17]:10

Early-modern Europe

During the 17th century, the concept of childhood began to emerge in Europe. Adults saw children as separate beings, innocent and in need of protection and training by the adults around them.[11]:6–7[17]:9 The English philosopher John Locke developed his theory of the tabula rasa in his 1690 An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. In Locke's philosophy, tabula rasa was the theory that the (human) mind is at birth a "blank slate" without rules for processing data, and that data is added and rules for processing are formed solely by one's sensory experiences. A corollary of this doctrine was that the mind of the child was born blank, and that it was the duty of the parents to imbue the child with correct notions. Locke himself emphasized the importance of providing children with "easy pleasant books" to develop their minds rather than using force to compel them; "children may be cozen'd into a knowledge of the letters; be taught to read, without perceiving it to be anything but a sport, and play themselves into that which others are whipp'd for." He also suggested that picture books be created for children.

Another influence on this shift in attitudes came from Puritanism, which stressed the importance of individual salvation. Puritans were concerned with the spiritual welfare of their children, and there was a large growth in the publication of "good godly books" aimed squarely at children.[9] Some of the most popular works were by James Janeway, but the most enduring book from this movement, still widely read today , was The Pilgrim's Progress (1678) by John Bunyan.

Chapbooks, pocket-sized pamphlets that were often folded instead of being stitched,[7]:32 were published in Britain; illustrated by woodblock printing, these inexpensive booklets reprinted popular ballads, historical re-tellings, and folk tales. Though not specifically published for children at this time, young people enjoyed the booklets as well.[17]:8 Johanna Bradley says, in From Chapbooks to Plum Cake, that chapbooks kept imaginative stories from being lost to readers under the strict Puritan influence of the time.[13]:17

Hornbooks also appeared in England during this time, teaching children basic information such as the alphabet and the Lord's Prayer.[18] These were brought from England to the American colonies in the mid-17th century. The first such book was a catechism for children written in verse by the Puritan John Cotton. Known as Spiritual Milk for Boston Babes, it was published in 1646, appearing both in England and Boston. Another early book, The New England Primer, was in print by 1691 and used in schools for 100 years. The primer begins, "In Adam's fall We sinned all ...", and continues through the alphabet. It also contained religious maxims, acronyms, spelling help and other educational items, all decorated by woodcuts.[7]:35

In 1634, the Pentamerone from Italy became the first major published collection of European folk tales. Charles Perrault began recording fairy tales in France, publishing his first collection in 1697. They were not well received among the French literary society, who saw them as only fit for old people and children. In 1658, Jan Ámos Comenius in Bohemia published the informative illustrated Orbis Pictus, for children under six learning to read. It is considered to be the first picture book produced specifically for children.[17]:7

The first Danish children's book was The Child's Mirror by Niels Bredal in 1568, an adaptation of a Courtesy book by the Dutch priest Erasmus. A Pretty and Splendid Maiden's Mirror, an adaptation of a German book for young women, became the first Swedish children's book upon its 1591 publication.[1]:700, 706 Sweden published fables and a children's magazine by 1766.

In Italy, Giovanni Francesco Straparola released The Facetious Nights of Straparola in the 1550s. Called the first European storybook to contain fairy-tales, it eventually had 75 separate stories and written for an adult audience.[19] Giulio Cesare Croce also borrowed from stories children enjoyed for his books.[20]:757

Russia's earliest children's books, primers, appeared in the late 16th century. An early example is ABC-Book, an alphabet book published by Ivan Fyodorov in 1571.[1]:765 The first picture book published in Russia, Karion Istomin's The Illustrated Primer, appeared in 1694.[1]:765 Peter the Great's interest in modernizing his country through Westernization helped Western children's literature dominate the field through the 18th century.[1]:765 Catherine the Great wrote allegories for children, and during her reign, Nikolai Novikov started the first juvenile magazine in Russia.[1]:765

Origins of the modern genre

The modern children's book emerged in mid-18th-century England.[21] A growing polite middle-class and the influence of Lockean theories of childhood innocence combined to create the beginnings of childhood as a concept. A Little Pretty Pocket-Book, written and published by John Newbery, is widely considered the first modern children's book, published in 1744. It was a landmark as the first children's publication aimed at giving enjoyment to children,[22] containing a mixture of rhymes, picture stories and games for pleasure.[23] Newbery believed that play was a better enticement to children's good behavior than physical discipline,[24] and the child was to record his or her behavior daily.

The book was child–sized with a brightly colored cover that appealed to children—something new in the publishing industry. Known as gift books, these early books became the precursors to the toy books popular in the 19th century.[25] Newbery was also adept at marketing this new genre. According to the journal The Lion and the Unicorn, "Newbery's genius was in developing the fairly new product category, children's books, through his frequent advertisements ... and his clever ploy of introducing additional titles and products into the body of his children's books."[26][27]

The improvement in the quality of books for children, as well as the diversity of topics he published, helped make Newbery the leading producer of children's books in his time. He published his own books as well as those by authors such as Samuel Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith;[7]:36[28] the latter may have written The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes, Newbery's most popular book.

Another philosopher who influenced the development of children's literature was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, who argued that children should be allowed to develop naturally and joyously. His idea of appealing to a children's natural interests took hold among writers for children.[7]:41 Popular examples included Thomas Day's The History of Sandford and Merton, four volumes that embody Rousseau's theories. Furthermore, Maria and Richard Lovell Edgeworth's Practical Education: The History of Harry and Lucy (1780) urged children to teach themselves.[29]

Rousseau's ideas also had great influence in Germany, especially on German Philanthropism, a movement concerned with reforming both education and literature for children. Its founder, Johann Bernhard Basedow, authored Elementarwerk as a popular textbook for children that included many illustrations by Daniel Chodowiecki. Another follower, Joachim Heinrich Campe, created an adaptation of Robinson Crusoe that went into over 100 printings. He became Germany's "outstanding and most modern"[1]:736 writer for children. According to Hans-Heino Ewers in The International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature, "It can be argued that from this time, the history of European children's literature was largely written in Germany."[1]:737

In the early 19th century, Danish author and poet Hans Christian Andersen traveled through Europe and gathered many well-known fairy tales.[30] He was followed by the Brothers Grimm, who preserved the traditional tales told in Germany.[20]:184 They were so popular in their home country that modern, realistic children's literature began to be looked down on there. This dislike of non-traditional stories continued there until the beginning of the next century.[1]:739–740 The Grimms's contribution to children's literature goes beyond their collection of stories, as great as that is. As professors, they had a scholarly interest in the stories, striving to preserve them and their variations accurately, recording their sources.[7]:259

A similar project was carried out by the Norwegian scholars Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe, who collected Norwegian fairy tales and published them as Norwegian Folktales, often referred to as Asbjørnsen and Moe. By compiling these stories, they preserved Norway's literary heritage and helped create the Norwegian written language.[7]:260

In Switzerland, Johann David Wyss published The Swiss Family Robinson in 1812, with the aim of teaching children about family values, good husbandry, the uses of the natural world and self-reliance. The book became popular across Europe after it was translated into French by Isabelle de Montolieu.

Golden age

The shift to a modern genre of children's literature occurred in the mid-19th century, as the didacticism of a previous age began to make way for more humorous, child-oriented books, more attuned to the child's imagination. The availability of children's literature greatly increased as well, as paper and printing became widely available and affordable, the population grew and literacy rates improved.[1]:654–655

Tom Brown's School Days by Thomas Hughes appeared in 1857, and is considered to be the founding book in the school story tradition.[31]:7–8 However, it was Lewis Carroll's fantasy, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1865 in England, that signaled the change in writing style for children to an imaginative and empathetic one. Regarded as the first "English masterpiece written for children"[7]:44 and as a founding book in the development of fantasy literature, its publication opened the "First Golden Age" of children's literature in Britain and Europe that continued until the early 1900s.[31]:18 Another important book of that decade was The Water-Babies, A Fairy Tale for a Land Baby, by Reverend Charles Kingsley (1862), which became extremely popular in England, and remains a classic of British children's literature.

In 1883, Carlo Collodi wrote the first Italian fantasy novel, The Adventures of Pinocchio, which was translated many times. In that same year, Emilio Salgari, the man who would become "the adventure writer par excellence for the young in Italy"[32] gave birth to his most legendary character Sandokan. In Britain, The Princess and the Goblin and its sequel The Princess and Curdie, by George MacDonald, appeared in 1872 and 1883, and the adventure stories Treasure Island and Kidnapped, both by Robert Louis Stevenson, were extremely popular in the 1880s. Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book was first published in 1894, and J. M. Barrie told the story of Peter Pan in the novel Peter and Wendy in 1911. Johanna Spyri's two-part novel Heidi was published in Switzerland in 1880 and 1881.[1]:749 In the US, children's publishing entered a period of growth after the American Civil War in 1865. Boys' book writer Oliver Optic published over 100 books. In 1868, the "epoch-making book"[7]:45 Little Women, the fictionalized autobiography of Louisa May Alcott, was published. This "coming of age" story established the genre of realistic family books in the United States. Mark Twain released Tom Sawyer in 1876, and in 1880 another bestseller, Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings, a collection of African American folk tales adapted and compiled by Joel Chandler Harris, appeared.[1]:478

Recent national traditions

China

The Chinese Revolution of 1911 and World War II brought political and social change that revolutionized children's literature in China. Western science, technology, and literature became fashionable. China's first modern publishing firm, Commercial Press, established several children's magazines, which included Youth Magazine, and Educational Pictures for Children.[1]:832–833 The first Chinese children's writer was Sun Yuxiu, an editor of Commercial Press, whose story The Kingdom Without a Cat was written in the language of the time instead of the classical style used previously. Yuxiu encouraged novelist Shen Dehong to write for children as well. Dehong went on to rewrite 28 stories based on classical Chinese literature specifically for children. In 1932, Zhang Tianyi published Big Lin and Little Lin, the first full-length Chinese novel for children.[1]:833–834

The Chinese Revolution of 1949 changed children's literature again. Many children's writers were denounced, but Tianyi and Ye Shengtao continued to write for children and created works that aligned with Maoist ideology. The 1976 death of Mao Zedong provoked more changes sweep China. Many writers from the early part of the century were brought back, and their work became available again. In 1990, General Anthology of Modern Children's Literature of China, a fifteen-volume anthology of children's literature since the 1920s, was released.[1]:834–835

Europe

Britain

The Golden Age of Children's Literature ended with World War I in Great Britain and Europe, and the period before World War II was much slower in children's publishing. The main exceptions in England were the publications of Winnie-the-Pooh by A. A. Milne in 1926 and The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien in 1937.[1]:682–683 T. H. White's sequence of Arthurian novels, The Once and Future King, began with The Sword in the Stone, published in 1938. In 1941, children's paperback books were first released in England under the Puffin Books imprint, and their lower prices helped make book buying possible for children during World War II.[1]:475–476

In the 1950s, the book market in Europe began recovering from the effects of two world wars. In Britain, C. S. Lewis published the first installment of The Chronicles of Narnia series in 1950, Dodie Smith's The Hundred and One Dalmatians was published in 1956, and Roald Dahl wrote Charlie and the Chocolate Factory in 1964. Children's fantasy literature remained strong in Great Britain throughout the 20th century. In Wales, the Welsh Joint Education Committee and the Welsh Books Council encouraged the publication of children's books in the Welsh language as well as books in English about Wales.

Continental Europe

The period from 1890 until World War I is considered the Golden Age of Children's Literature in Scandinavia. Erik Werenskiold, Theodor Kittelsen, and Dikken Zwilgmeyer were especially popular, writing folk and fairy tales as well as realistic fiction. The 1859 translation into English by George Webbe Dasent helped increase the stories' influence.[1]:705 One of the most influential and internationally most successful Scandinavian children's books from this period is Selma Lagerlöfs The Wonderful Adventures of Nils.

The interwar period saw a slow-down in output similar to Britain, although "one of the first mysteries written specifically for children", Emil and the Detectives by Erich Kästner, was published in Germany in 1930.[20]:315

The period during and following World War II became the Classical Age of the picture book in Switzerland, with works by Alois Carigiet, Felix Hoffmann, and Hans Fischer.[1]:683–685, 399, 692, 697, 750 1963 was the first year of the Bologna Children's Book Fair in Italy, which was described as "the most important international event dedicated to the children's publishing".[33] For four days it brings together writers, illustrators, publishers, and book buyers from around the world.[33]

Russia and USSR

In Russia, Russian fairy tales were introduced to children literature by Aleksandr Afanasyev in his children's edition of his eight-volume Russian Folk Tales in 1871. By the 1860s, literary realism and non-fiction dominated children's literature. More schools were started, using books by writers like Konstantin Ushinsky and Leo Tolstoy, whose Russian Reader included an assortment of stories, fairy tales, and fables. Books written specifically for girls developed in the 1870s and 1880s. Publisher and journalist Evgenia Tur wrote about the daughters of well-to-do landowners, while Aleksandra Annenskaya's stories told of middle-class girls working to support themselves. Vera Zhelikhovsky, Elizaveta Kondrashova, and Nadezhda Lukhmanova also wrote for girls during this period.[1]:767

Children's non-fiction gained great importance in Russia at the beginning of the century. A ten-volume children's encyclopedia was published between 1913 and 1914. Vasily Avenarius wrote fictionalized biographies of important people like Nikolai Gogol and Alexander Pushkin around the same time, and scientists wrote for books and magazines for children. Children's magazines flourished, and by the end of the century there were 61. Lidia Charskaya and Klavdiya Lukashevich continued the popularity of girls' fiction. Realism took a gloomy turn by frequently showing the maltreatment of children from lower classes. The most popular boys' material was Sherlock Holmes, and similar stories from detective magazines.[1]:768

The state took control of children's literature during the October Revolution. Maksim Gorky edited the first children's, Northern Lights, under Soviet rule. People often label the 1920s as the Golden Age of Children's Literature in Russia.[1]:769 Samuil Marshak led that literary decade as the "founder of (Soviet) children's literature".[34]:193 As head of the children's section of the State Publishing House and editor of several children's magazines, Marshak exercised enormous influence by[34]:192–193 recruiting Boris Pasternak and Osip Mandelstam to write for children.

In 1932, professional writers in the Soviet Union formed the USSR Union of Writers, which served as the writer's organization of the Communist Party. With a children's branch, the official oversight of the professional organization brought children's writers under the control of the state and the police. Communist principles like collectivism and solidarity became important themes in children's literature. Authors wrote biographies about revolutionaries like Lenin and Pavlik Morozov. Alexander Belyayev, who wrote in the 1920s and 1930s, became Russia's first science fiction writer.[1]:770 According to Ben Hellman in the International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature, "war was to occupy a prominent place in juvenile reading, partly compensating for the lack of adventure stories", during the Soviet Period.[1]:771 More political changes in Russia after World War II brought further change in children's literature. Today, the field is in a state of flux because some older authors are being rediscovered and others are being abandoned.[1]:772

India

Christian missionaries first established the Calcutta School-Book Society in the 19th century, creating a separate genre for children's literature in that country. Magazines and books for children in native languages soon appeared.[1]:808 In the latter half of the century, Raja Shivprasad wrote several well-known books in Hindustani.[1]:810 A number of respected Bengali writers began producing Bengali literature for children including Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, who translated some stories and wrote others himself. Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore wrote plays, stories, and poems for children, including one work illustrated by painter Nandalal Bose. They worked from the end of the 19th century into the beginning of the 20th century. Tagore's work was later translated into English, with Bose's pictures.[1]:811 Behari Lal Puri was the earliest writer for children in Punjabi. His stories were didactic in nature.[1]:815

The first full-length children's book was Khar Khar Mahadev by Narain Dixit, which was serialized in one of the popular children's magazines in 1957. Other writers include Premchand, and poet Sohan Lal Dwivedi.[1]:811 In 1919, Sukumar Ray wrote and illustrated nonsense rhymes in the Bengali language, and children's writer and artist Abanindranath Tagore finished Barngtarbratn. Bengali children's literature flourished in the later part of the twentieth century. Educator Gijubhai Badheka published over 200 children's books in the Gujarati language, and many of them are still popular.[1]:812 In 1957, political cartoonist K. Shankar Pillai founded the Children's Book Trust publishing company. The firm became known for high quality children's books, and many of them were released in several languages. One of the most distinguished writers is Pandit Krushna Chandra Kar in Oriya literature, who wrote many good books for children, including Pari Raija, Kuhuka Raija, Panchatantra, and Adi Jugara Galpa Mala. He wrote biographies of many historical personalities, such as Kapila Deva. In 1978, the firm organized a writers' competition to encourage quality children's writing. The following year, the Children's Book Trust began a writing workshop and organized the First International Children's Book Fair in New Delhi.[1]:809 Children's magazines, available in many languages, were widespread throughout India during this century.[1]:811–820

United States

One of the most famous books of American children's literature is L. Frank Baum's fantasy novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900. "By combining the English fondness for word play with the American appetite for outdoor adventure", Connie Epstein in International Companion Encyclopedia Of Children's Literature says Baum "developed an original style and form that stands alone".[1]:479 Baum wrote thirteen more Oz novels, and other writers continued the Oz series into the twenty-first century.

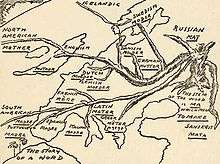

Demand continued to grow in North America between World War I and World War II, helped by the growth of libraries in both Canada and the United States. Children's reading rooms in libraries, staffed by specially trained librarians, helped create demand for classic juvenile books. Reviews of children's releases began appearing regularly in Publishers Weekly and in The Bookman magazine began to regularly publish reviews of children's releases, and the first Children's Book Week was launched in 1919. In that same year, Louise Seaman Bechtel became the first person to head a juvenile book publishing department in the country. She was followed by May Massee in 1922, and Alice Dalgliesh in 1934.[1]:479–480

The American Library Association began awarding the Newbery Medal, the first children's book award, in 1922.[35] The Caldecott Medal for illustration followed in 1938.[36] The first book by Laura Ingalls Wilder about her life on the American frontier, Little House in the Big Woods appeared in 1932.[20]:471 In 1937 Dr. Seuss published his first book, entitled, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. The young adult book market developed during this period, thanks to sports books by popular writer John R. Tunis', the novel Seventeenth Summer by Maureen Daly, and the Sue Barton nurse book series by Helen Dore Boylston.[37]:11

The already vigorous growth in children's books became a boom in the 1950s, and children's publishing became big business.[1]:481 In 1952, American journalist E. B. White published Charlotte's Web, which was described as "one of the very few books for young children that face, squarely, the subject of death".[20]:467 Maurice Sendak illustrated more than two dozen books during the decade, which established him as an innovator in book illustration.[1]:481 The Sputnik crisis that began in 1957, provided increased interest and government money for schools and libraries to buy science and math books and the non-fiction book market "seemed to materialize overnight".[1]:482

Classification

Children's literature can be divided into a number of categories, but it is most easily categorized according to genre or the intended age of the reader.

By genre

A literary genre is a category of literary compositions. Genres may be determined by technique, tone, content, or length. According to Anderson,[38] there are six categories of children's literature (with some significant subgenres):

- Picture books, including concept books that teach the alphabet or counting for example, pattern books, and wordless books.

- Traditional literature, including folktales, which convey the legends, customs, superstitions, and beliefs of people in previous civilizations. This genre can be further broken into subgenres: myths, fables, legends, and fairy tales

- Fiction, including fantasy, realistic fiction, and historical fiction

- Non-fiction

- Biography and autobiography

- Poetry and verse.

By age category

The criteria for these divisions are vague, and books near a borderline may be classified either way. Books for younger children tend to be written in simple language, use large print, and have many illustrations. Books for older children use increasingly complex language, normal print, and fewer (if any) illustrations. The categories with an age range are listed below:

- Picture books, appropriate for pre-readers or children ages 0–5.

- Early reader books, appropriate for children ages 5–7. These books are often designed to help a child build his or her reading skills.

- Chapter books, appropriate for children ages 7–12.

- Short chapter books, appropriate for children ages 7–9.

- Longer chapter books, appropriate for children ages 9–12.

- Young-adult fiction, appropriate for children ages 12–18.

Illustration

Pictures have always accompanied children's stories.[8]:320 A papyrus from Byzantine Egypt, shows illustrations accompanied by the story of Hercules' labors.[39] Modern children's books are illustrated in a way that is rarely seen in adult literature, except in graphic novels. Generally, artwork plays a greater role in books intended for younger readers (especially pre-literate children). Children's picture books often serve as an accessible source of high quality art for young children. Even after children learn to read well enough to enjoy a story without illustrations, they continue to appreciate the occasional drawings found in chapter books.

According to Joyce Whalley in The International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature, "an illustrated book differs from a book with illustrations in that a good illustrated book is one where the pictures enhance or add depth to the text."[1]:221 Using this definition, the first illustrated children's book is considered to be Orbis Pictus which was published in 1658 by the Moravian author Comenius. Acting as a kind of encyclopedia,Orbis Pictus had a picture on every page, followed by the name of the object in Latin and German. It was translated into English in 1659 and was used in homes and schools around Europe and Great Britain for years.[1]:220

Early children's books, such as Orbis Pictus, were illustrated by woodcut, and many times the same image was repeated in a number of books regardless of how appropriate the illustration was for the story.[8]:322 Newer processes, including copper and steel engraving were first used in the 1830s. One of the first uses of Chromolithography (a way of making multi-colored prints) in a children's book was demonstrated in Struwwelpeter, published in Germany in 1845. English illustrator Walter Crane refined its use in children's books in the late 19th century.

Another method of creating illustrations for children's books was etching, used by George Cruikshank in the 1850s. By the 1860s, top artists were illustrating for children, including Crane, Randolph Caldecott, Kate Greenaway, and John Tenniel. Most pictures were still black-and-white, and many color pictures were hand colored, often by children.[1]:224–226 The Essential Guide to Children's Books and Their Creators credits Caldecott with "The concept of extending the meaning of text beyond literal visualization".[20]:350

Twentieth-century artists such as Kay Nielson, Edmund Dulac, and Arthur Rackham produced illustrations that are still reprinted today.[1]:224–227 Developments in printing capabilities were reflected in children's books. After World War II, offset lithography became more refined, and painter-style illustrations, such as Brian Wildsmith's were common by the 1950s.[1]:233

Scholarship

Professional organizations, dedicated publications, individual researchers and university courses conduct scholarship on children's literature. Scholarship in children's literature is primarily conducted in three different disciplinary fields: literary studies/cultural studies (literature and language departments and humanities), library and information science, and education. (Wolf, et al., 2011).

Typically, children's literature scholars from literature departments in universities (English, German, Spanish, etc. departments), cultural studies, or in the humanities conduct literary analysis of books. This literary criticism may focus on an author, a thematic or topical concern, genre, period, or literary device and may address issues from a variety of critical stances (poststructural, postcolonial, New Criticism, psychoanalytic, new historicism, etc.). Results of this type of research are typically published as books or as articles in scholarly journals.

The field of Library and Information Science has a long history of conducting research related to children's literature.

Most educational researchers studying children's literature explore issues related to the use of children's literature in classroom settings. They may also study topics such as home use, children's out-of-school reading, or parents' use of children's books. Teachers typically use children's literature to augment classroom instruction.

Literary Criticism

Controversies often emerge around the content and characters of prominent children’s books.[40][41] Well-known classics that remain popular throughout decades[42] commonly become criticized by critics and readers as the values of contemporary culture change.[43][44][45] Critical analysis of children’s literature is common through children's literary journals as well as published collections of essays contributed to by psychoanalysts, scholars and various literary critics such as Peter Hunt.

Stereotypes, racism and cultural bias

Popular classics such as The Secret Garden, Pippi Longstocking, Peter Pan, The Chronicles of Narnia and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory have been criticized for their racial stereotyping of minorities and marginalized cultures.[40][46][47][48] The academic journal Children’s Literature Review has provided sources of critical analysis of many well known children’s books. In its 114th volume, the journal discuses the damaging cultural stereotypes in Belgian cartoonist Herge’s Tintin series in reference to its depiction of people from the Congo.[49] The Five Chinese Brothers, written by Claire Huchet Bishop and illustrated by Kurt Wiese has been criticized for its stereotypical caricatures of Chinese people.[50] Helen Bannerman’s The Story of Little Black Sambo and Florence Kate Upton’s The Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and a Golliwogg have also been noted for their racist and controversial depictions, becoming "emblems of racism".[51] The term sambo, is a considered a racial slur from the American South causing a widespread ban of Bannerman's book.[52] Author Julius Lester and illustrator Jerry Pinkney revised the story as Sam and the Tigers: A New Telling of Little Black Sambo, making its content more appropriate and empowering for children of colour.[53] Feminist theologian Dr. Eske Wollrad claimed Astrid Lindgren's Pippi Longstocking novels “have colonial racist stereotypes”,[46] urging parents to skip specific offensive passages when reading to their children. Criticisms of the 1911 novel The Secret Garden by author Frances Hodgson Burnett claim endorsement of racist attitudes toward black people through the dialogue of main character Mary Lennox, symbology and as a running theme throughout the novel.[54][55][56] Hugh Lofting's The Story of Doctor Dolittle has been accused of “white racial superiority”,[57] suggesting through its underlying message that a person of colour is less human than animal.[58]

The picture book The Snowy Day, written and illustrated by Ezra Jack Keats was published in 1962 and is known as the first picture book to portray an African-American child as a protagonist. It has been noted that still many children of colour remain underrepresented in North American picture books such as Middle Eastern and Central American protagonists.[59] In his interview in the book Ways of Telling: Conversations on the Art of the Picture Book, Jerry Pinkney mentioned how difficult it was find children's books with black children as characters.[60] In the literary journal The Black Scholar, Bettye I. Latimer has criticized popular children’s books for their renditions of people as almost exclusively white, stating Dr. Seuss books lack depictions of people of colour.[61] The popular school readers Fun with Dick and Jane which ran from the 1930s until the 1970s, are known for their whitewashed renditions of the North American nuclear family as well as their highly gendered stereotypes. The first black family didn't appear in the series until the 1960s, thirty years into its run.[62][63][64]

Writer Mary Renck Jalongo In Young Children and Picture Books discusses damaging stereotypes of Native Americans in children's literature, stating repeated depictions of indigenous people as living in the 1800s with feathers and face paint cause children to mistake them as fictional and not as people that still exist today.[65] The depictions of Native American people in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie and J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan are widely discussed among critics. Wilder’s novel, based on her childhood in America’s midwest in the late 1800s, portrays Native Americans as racialized stereotypes and has been banned in some classrooms.[66] In her essay, Somewhere Outside the Forest: Ecological Ambivalence in Neverland from The Little White Bird to Hook, writer M. Lynn Byrd describes how the natives of Neverland are depicted as "uncivilized," valiant fighters unafraid of death and are referred to as “redskins”, now considered a racial slur.[67][68]

The Empire, imperialism and colonialism

The presence of empire as well as pro-colonialist and imperialist themes in children’s literature have been identified in some of the most well known children’s classics of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Scholars note that this was a way of perpetuating and guaranteeing that the values and ideologies of a culture were successfully passed on to the next generation.[69][70][71]

In the French illustrator Jean de Brunhoff’s 1931 picture book Histoire de Babar, le petit elephant (The Story of Babar, The Little Elephant), prominent themes of imperialism and colonialism have been commonly noted and identified as propaganda. Said to be an allegory for French colonialism, Babar easily assimilates himself into the bourgeois lifestyle. It is a world where the adapted elephants dominate the animals who have not yet been assimilated into the new and powerful civilization.[72][73][74][75] H. A. Rey and Margret Rey’s Curious George first published in 1941 has been criticized for its blatant slave and colonialist narratives. Critics claim The Man with the Yellow Hat represents a colonialist poacher of European descent who kidnaps George, a native from Africa, and sends him on a ship to America. Details such as the man in colonialist uniform and Curious George's lack of tail are points in this argument. In an article, The Wall Street Journal interprets it as a “barely disguised slave narrative." [76][77][78] Rudyard Kipling, the author of Just So Stories and The Jungle Book has also been accused of colonial prejudice attitudes that have been connected to his writings.[79] Literary critic Jean Webb, among others, has pointed out the presence of British Imperialism in The Secret Garden. The protagonist, Mary Lennox and her friends are said to be portrayed as innocent victims of Imperialism.[80][81] Colonialist ideology has been identified as a prominent element in Peter Pan by critics.[82][83]

Gender roles and representation of women

In her book Children’s Literature: From the fin de siècle to the new millennium, professor Kimberley Reynolds claims gender division stayed in children's books prominently until the 1990s when a shift began to take place. She also says that capitalism encourages gender-specific marketing of books and toys.[84] Adventure stories have been identified as being for boys and domestic fiction intended for girls.[85] Publishers often believe that boys will not read stories about girls, but that girls will read stories about both boys and girls; therefore, a story that features male characters is expected to sell better.[86] The interest in appealing to boys is also seen in the Caldecott awards, which tend to be presented to books that are believed to appeal to boys.[86]

Reynolds also says that both boys and girls have been presented by limited representations of appropriate behaviour, identities and careers through the illustrations and text of children’s literature. She argues girls have traditionally been marketed books that feminize them in order to prepare them for domestic jobs and motherhood. Conversely, boys are conditioned through characters that encourage bureaucracy and war.[87] Introducing Children's Literature: From Romanticism to Postmodernism argues children’s fiction colonizes the reader in order to implant hegemonic ideologies that support gender roles.[88] I’m Glad I’m a Boy! I’m Glad I’m a Girl! (1970) by Whitney Darrow, Jr. was criticized for its narrow depictions of careers for both boys and girls. The book instructs the reader that boys are doctors, policemen, pilots, and Presidents while girls are nurses, meter maids, stewardesses and First Ladies.[89] Growing up with Dick and Jane highlights the heterosexual, nuclear family and also points out the gender-specific duties of the Mother, Father, Brother and Sister.[90] Young Children and Picture Books encourages readers to avoid books with women who are portrayed as inactive and unsuccessful as well as intellectually inferior and subservient to their fellow male characters to avoid children’s books that have repressive and sexist stereotypes for women.[59]

In addition to perpetuating stereotypes about appropriate behavior and occupations for women and girls, children's books frequently lack female characters entirely, or include them only as minor or unimportant characters.[86] In the book Boys and Girls Forever: Reflections on Children's Classics, scholar Alison Lurie says most adventure novels of the 20th century, with few exceptions, contain boy protagonists while female characters in books such as those by Dr. Seuss, would typically be assigned the gender-specific roles of receptionists and nurses.[91] The Winnie-the-Pooh characters written by A. A. Milne, have been pointed out as being primarily male, with the exception of the character Kanga, who is a mother to Roo.[92] Even animals and inanimate objects are usually identified as being male in children's books.[86] The near-absence of significant female characters is paradoxical because of the role of women in creating children's literature.[86]

Some of the earliest children’s stories to be referred by critics to contain feminist themes are Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women and Frank L. Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. With many women of this period being represented in children’s books as doing housework, these two books deviated from this pattern. Drawing attention to the perception of housework as oppressive is one of the earliest forms of the feminist movement. Little Women, a story about four sisters, is said to show power of women in the home and is seen as both conservative and radical in nature. The character of Jo is observed as having a rather contemporary personality and has even been pinned as a representation of the feminist movement. The feminist themes in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz are speculated to be the influence of Baum's mother-in law, Matilda Gage, an important figure in the suffragist movement. His significant political commentary on capitalism, and racial oppression are also said to be part of Gage's influence. Examples made of these themes is the main protagonist, Dorothy who is punished by being made to do housework. Another example made of positive representations of women is in Finnish author Tove Jansson's Moomin series which features strong and individualized female characters.[93] In recent years, there has been a surge in the production and availability of feminist children's literature as well as gender neutrality in children's literature.

Debate over controversial content

A widely discussed and debated topic by critics and publishers in the children’s book industry is whether outdated and offensive content, specifically racial stereotypes, should be changed upon the printing of new editions. Some question if certain books should be banned[44] while others believe original content should remain but publishers should make additions that guide parents[94] in conversations with their children about the problematic elements of the particular story.[95][96] Some see racist stereotypes as cultural artifacts that should be preserved.[97] In The Children’s Culture Reader, scholar Henry Jenkins references Herbert Kohl’s essay Should We Burn Babar? which raises the debate whether children should be educated on how to think critically towards oppressive ideologies rather than ignore historical mistakes. Jenkins suggests that parents and educators should trust children to make responsible judgments.[98]

Some books have been altered in newer editions and significant changes can be seen, such as illustrator Richard Scarry’s book Best Word Book Ever.[99] and Roald Dahl’s book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.[96] In other cases classics have been rewritten into updated versions by new authors and illustrators. Several versions of Little Black Sambo have been remade as more appropriate and without prejudice.[100]

Effect on early childhood development

Some childhood psychologists have argued the importance and influence childhood stories have on children, such as Bruno Bettelheim. In his book The Uses of Enchantment, he uses psychoanalysis to examine the impact that Fairy Tales have on the developing child. Bettelheim states the unconscious mind of a child is affected by the message behind a story and thus, it shapes their perception and guides their development.[101] Author and illustrator Anthony Browne contends the early viewing of an image in a picture book leaves an important and lasting impression on a child.[102] According to research, a child’s most crucial individual characteristics are developed in their first five years. Their environment and interaction with images in picture books have a profound impact on this development and are intended to inform a child about the world.[103]

Children’s literature critic Peter Hunt argues that no book is innocent of harbouring an ideology of the culture it comes from.[104] Some critics claim that an author’s ethnicity, gender and social class inform their work.[105] Scholar Kimberley Reynolds suggests books can never be neutral as their nature is intended as instructional and by using its language, children are imbedded with the values of that society.[106] Claiming childhood as a culturally constructed concept,[107] Reynolds states that it is through children’s literature that a child learns how to form their behaviour and to act as a child should by the expectations of the culture they are a part of. She also attributes capitalism as a prominent means of instructing our children in their behaviours, specifically middle class children.[87] The “image of childhood”[108] is said to be created and perpetuated by adults to affect children "at their most susceptible age”.[109] Kate Greenaway’s illustrations are used as an example of imagery intended to instruct a child in the proper way to look and behave.[108] In Roberta Slinger Trites book Disturbing the Universe: Power and Repression in Adolescent Literature, she also argues adolescence is a social construct established by ideologies present in literature.[110] In the study The First R: How Children Learn About Race and Racism, researcher Debra Ausdale studies children in multiethnic daycare centres. Ausdale claims children as young as three have already entered into and begun experimenting with the race ideologies of the adult world. She asserts racist attitudes are assimilated[111] using interactions children have with books as an example of how children internalize what they encounter in real life.[112]

Awards

Many noted awards for children's literature exist in various countries:

- In Africa, The Golden Baobab Prize runs an annual competition for African writers of children's stories. It is one of the few African literary awards that recognizes writing for children and young adults. The competition is the only pan-African writing competition that recognizes promising African writers of children's literature. Every year, the competition invites entries of unpublished African-inspired stories written for an audience of 8- to 11-year-olds (Category A) or 12- to 15-year-olds (Category B). The writers who are aged 18 or below, are eligible for the Rising Writer Prize.

- In Australia, the Children's Book Council of Australia runs a number of annual CBCA book awards

- In Canada, the Governor General's Literary Award for Children's Literature and Illustration, in English and French, is established. A number of the provinces' school boards and library associations also run popular "children's choice" awards where candidate books are read and championed by individual schools and classrooms. These include the Blue Spruce (grades K-2) Silver Birch Express (grades 3–4), Silver Birch (grades 5–6) Red Maple (grades 7–8) and White Pine (high school) in Ontario. Programs in other provinces include The Red Cedar and Stellar Awards in BC, the Willow Awards in Saskatchewan, and the Manitoba Young Readers Choice Awards. IBBY Canada offers a number of annual awards.

- In the Philippines, The Carlos Palanca Memorial Award for Literature for short story literature in the English and Filipino languages (Maikling Kathang Pambata) has been established since 1989. The Children's Poetry in the English and Filipino languages has been established since 2009. The Pilar Perez Medallion for Young Adult Literature was awarded in 2001 and 2002. The Philippine Board on Books for Young People gives major awards, which include the PBBY-Salanga Writers' Prize for excellence in writing and the PBBY-Alcala Illustrator's Prize for excellence in illustration. Other awards are The Ceres Alabado Award for Outstanding Contribution in Children's Literature; the Gintong Aklat Award (Golden Book Award); The Gawad Komisyon para sa Kuwentong Pambata (Commission Award for Children's Literature in Filipino) and the National Book Award (given by the Manila Critics' Circle) for Outstanding Production in Children's Books and young adult literature.

- In the United Kingdom and Commonwealth, the Carnegie Medal for writing and the Kate Greenaway Medal for illustration, the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize, and the Guardian Award are a few notable awards.

- In the United States, the American Library Association Association for Library Service to Children give the major awards. They include the Newbery Medal for writing, Michael L. Printz Award for writing for teens, Caldecott Medal for illustration, Golden Kite Award in various categories from the SCBWI, Sibert Medal for informational, Theodor Seuss Geisel Award for beginning readers, Laura Ingalls Wilder Medal for impact over time, Batchelder Award for works in translation, Coretta Scott King Award for work by an African-American writer, and the Belpre Medal for work by a Latino writer. Other notable awards are the National Book Award for Young People's Literature and the Orbis Pictus Award for excellence in the writing of nonfiction for children.

International awards also exist as forms of global recognition. These include the Hans Christian Andersen Award, the Astrid Lindgren Memorial Award, Ilustrarte Bienale for illustration, and the BolognaRagazzi Award for art work and design.[113] Additionally, bloggers with expertise on children's and young adult books give a major series of online book awards called The Cybils Awards, or, Children's and Young Adult Bloggers' Literary Awards.

See also

- Book talk

- Children's literature criticism

- Disability in children's literature

- International Children's Digital Library

- Internet Archive's Children's Library

- Native Americans in children's literature

- Young-adult literature

- Feminist children's literature

Lists

- List of children's book series

- List of children's classic books

- List of children's literature authors

- List of children's non-fiction writers

- List of fairy tales

- List of illustrators

- List of publishers of children's books

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 Hunt, Peter (editor) (1996). International Companion Encyclopedia Of Children's Literature. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-203-16812-7.

- ↑ Nodelman, Perry (2008). The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature. JHU. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-8018-8980-6.

- ↑ Library of Congress. "Children's Literature" (PDF). LIbrary of Congress Collections Policy Statement. Library of Congress. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- ↑ Chevalier, Tracy (1989). Twentieth-Century Children's Writers. Chicago: St. James Press. ISBN 0-912289-95-3.

- ↑ Anderson 2006, p. 2.

- ↑ Smith, Dinitia (June 24, 2000). "The Times Plans a Children's Best-Seller List". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Arbuthnot, May Hill (1964). Children and Books. United States: Scott, Foresman.

- 1 2 3 4 Lerer, Seth (2008). Children's Literature: A Reader's History, from Aesop to Harry Potter. University of Chicago.

- 1 2 "To Instruct and Delight A History of Children's Literature". Randon History. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- ↑ Nikolajeva, María (editor) (1995). Aspects and Issues in the History of Children's Literature. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-29614-7.

- 1 2 Shavit, Zohar (2009). Poetics of Children's Literature. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0-8203-3481-3.

- ↑ McMunn, Meradith Tilbury; William Robert McMunn (1972). "Children's Literature in the Middle Ages". Children's Literature 1: 21. doi:10.1353/chl.0.0064. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- 1 2 Bradley, Johanna (2007). From Chapbooks to Plumb Cake: The History of Children's Literature. ProQuest. ISBN 978-0-549-34070-6.

- ↑ Wyile, Andrea Schwenke (editor) (2008). Considering Children's Literature: A Reader. Broadview. p. 46.

- 1 2 Kline, Daniel T. (2003). Medieval Literature for Children. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-8153-3312-8.

- ↑ Ghaeni, Zohreh. "Asurik Tree: The Oldest Children's Story in Persian History". International Board on Books for Young People. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Reynolds, Kimberley (2011). Children's Literature: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia: Children's Literature. Columbia University Press. 2009.

- ↑ Opie, Iona; Peter Opie (1974). The Classic Fairy Tales. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-19-211559-6{{inconsistent citations}}

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Silvey, Anita (editor) (2002). The Essential Guide to Children's Books and their Creators. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-19082-1.

- ↑ "How the Newbery Award Got Its Name".

- ↑ "Early Children's Literature: From moralistic stories to narratives of everyday life".

- ↑ Marks, Diana F. (2006). Children's Book Award Handbook. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited. p. 201.

- ↑ Townsend, John Rowe. Written for Children. (1990). New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-446125-4, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Lundin, Anne H. (1994). "Victorian Horizons: The Reception of Children's Books in England and America, 1880–1900". The Library Quarterly (The University of Chicago Press) 64.

- ↑ Susina, Jan (June 1993). "Editor's Note: Kiddie Lit(e): The Dumbing Down of Children's Literature". The Lion and the Unicorn 17 (1): v–vi. doi:10.1353/uni.0.0256. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- ↑ Rose, p. 218.

- ↑ Rose, p. 219.

- ↑ Leader, Zachary, Reading Blake's Songs, p.3

- ↑ Elias Bredsdorff, Hans Christian Andersen: the story of his life and work 1805–75, Phaidon (1975) ISBN 0-7148-1636-1

- 1 2 Knowles, Murray (1996). Language and Control in Children's Literature. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-203-41975-5.

- ↑ Lawson Lucas, A. (1995) "The Archetypal Adventures of Emilio Salgari: A Panorama of his Universe and Cultural Connections New Comparison", A Journal of Comparative and General Literary Studies, Number 20 Autumn

- 1 2 "Italy | Bologna Children's Book Fair". Culture360. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- 1 2 Shrayer, Maxim (editor) (2007). An Anthology of Jewish-Russian Literature: 1801–1953. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-0521-4.

- ↑ "Newbery Awards". Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ↑ "Caldecott Medal Awards". Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ↑ Cart, Michael (2010). Young Adult Literature: From Romance to Realism. ALA Editions. ISBN 978-0-8389-1045-0.

- ↑ Anderson 2006

- ↑ Cribiore, Raffaella, Gymnastics of the Mind, pg. 139 Princeton University, 2001, cited in Lerer, Seth, Children's Literature, pg. 22, University of Chicago, 2008.

- 1 2 Arteaga, Juan; Champion, John. "The 6 Most Secretly Racist Classic Children's Books". CRACKED. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Jalongo, Mary Renk (2004). Young Children and Picture Books. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. pp. 17–20. ISBN 1-928896-15-4.

- ↑ Ciabattari, Jane. "The 11 greatest children's books". BBC culture. BBC. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Lurie, Alson (2003). Boys and Girls Forever: Reflections on Children's Classics. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 38.

- 1 2 ., Sharon. "Should We Ban "Little House" for Racism?". Adios Barbie. Adios Barbie. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Finan, Victoria. "BBC chooses best children's books of all time - do you agree?". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- 1 2 Flood, Alison. "Pippi Longstocking books charged with racism". the guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Byrd, M. Lynn (May 11, 2004). Wild Things: Children's Culture and Ecocriticism: Somewhere Outside the Forest: Ecological Ambivalence in Neverland from The Little White Bird to Hook. Detroit: Wayne State UP. p. 65. ISBN 0814330282.

- ↑ Richard, Olga; McCann; Donnarae (1973). The Child's First Books. New York: H.W. Wilson Company. p. 19. ISBN 0824205014.

- ↑ Burns, Tom (2006). "Tintin". Children's Literature Review 114: 3.

- ↑ Cai, Mingshui (2002). Multicultural Literature for Children and Young Adults. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 67&75.

- ↑ McCorquodale, Duncan (December 29, 2009). Illustrated Children's Books. London: Black Dog Publishing. p. 22.

- ↑ Jalongo, Mary Renck (2004). Young Children and Picture Books. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. p. 17.

- ↑ Marcus, Leonard S (2002). Ways of Telling: Conversations on the Art of the Picture Book. New York, N.Y: Dutton Children's. p. 164.

- ↑ Burns, Tom (2007). "The Secret Garden". Children's Literature Review. 122: 22–103.

- ↑ Arteaga, Juan; Champion, John. "The 6 Most Secretly Racist Classic Children's Books". Cracked. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Sprat, Jack. "Exploring the Classics: The Secret Garden". TreasuryIslands. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Egoff, Sheila A. (1981). Thursday's Child: Trends and Patterns in Contemporary Children's Literature. Chicago, Ill.: American Library Association. p. 248.

- ↑ Nodelman, Perry (2008). The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP. p. 71.

- 1 2 Jalongo, Mary Renck (2004). Young Children and Picture Books. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. p. 37.

- ↑ Marcus, Leonard S (2002). Ways of Telling: Conversations on the Art of the Picture Book. New York, N.Y: Dutton Children's. p. 157.

- ↑ Latimer, Bettye I. (1973). "Children's Books and Racism". The Black Scholar 4.8 (9): 21.

- ↑ Kismaric, Carole; Heiferman, Marvin (1996). Growing up with Dick and Jane: Learning and Living the American Dream. San Francisco: Collins San Francisco,. p. 98.

- ↑ Shabazz, Rika. "Dick and Jane and Primer Juxtaposition in "The Bluest Eye"". KALEIDO[SCOPES]: DIASPORA RE-IMAGINED. Williams College, Africana. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Wards, Jervette R. (April 1, 2012). "In Search of Diversity: Dick and Jane and Their Black Playmates". Making Connections 13 (2).

- ↑ Jalongo, Mary Renck (2004). Young Children and Picture Books. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. p. 39.

- ↑ Burns, Tom (2006). "Laura Ingalls Wilder 1867-1957". Children's Literature Review 111: 164.

- ↑ Dobrin, Sidney I (2004). Wild Things: Children's Culture and Ecocriticism. Detroit: Wayne State UP. p. 57.

- ↑ Nodelman, Perry (2008). The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature. Baltimore, Md: Johns Hopkins UP. p. 272.

- ↑ Reynolds, Kimberley (2012). Children's Literature from the Fin De Siecle to the New Millennium. Tavistock, Devon, U.K: Northcote House. p. 24.

- ↑ Thacker, Deborah Cogan; Webb, Jean (2002). Introducing Children's Literature: From Romanticism to Postmodernism. London: Routledge. London: Routledge. p. 91.

- ↑ Nodelman, Perry (2008). The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins United Press. p. 272.

- ↑ Burns, Tom (2006). "Babar". Children's Literature Review 116: 31.

- ↑ McCorquodale, Duncan (2009). Illustrated Children's Books. London: Black Dog Publishing. p. 43.

- ↑ WIELAND, RAOUL. "Babar The Elephant – Racism, Sexism, and Privilege in Children’s Storie". The Good Men Project. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Gopnik, Adam. "Freeing the Elephants: What Babar brought.". The New Yorker. The New Yorker. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Miller, John J. "Curious George's Journey to the Big Scree". The Wall Street Journal. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Munson, Kyle. "Does monkey tale speak of slavery?". The Des Moines Register. The Des Moines Register. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Peacock, Scot; Marion, Allison (2004). "Margret and H. A. Rey". Children's Literature Review 93: 77–99.

- ↑ McCorquodale, Duncan (2009). Illustrated Children's Books. London: Black Dog Publishing. p. 66.

- ↑ Webb, Jean; Thacker, Deborah Cogan (2002). Introducing Children's Literature: From Romanticism to Postmodernism. London: Routledge. p. 91.

- ↑ Burns, Tom (2007). "The Secret Garden". Children's Literature Review. 122: 33.

- ↑ Dobrin, Sydney I (2004). Wild Things: Children's Cultture and Ecocriticism. Detroit: Wayne State UP. p. 65.

- ↑ Stoddard Holms, Martha (2009). Peter Pan and the Possibilities of Child Literatue. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 138&144.

- ↑ Reynolds, Kimberley (2012). Children's Literature from the Fin De Siècle to the New Millennium. Tavistock, Devon, U.K: Northcote House. p. 6.

- ↑ Thacker, Deborah Cogan; Webb, Jean (2002). Introducing Children's Literature: From Romanticism to Postmodernism. London: Routledge. London: Routledge. p. 53.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yabroff, Jennie (2016-01-08). "Why are there so few girls in children’s books?". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- 1 2 Reynolds, Kimberley (2012). Children's Literature from the Fin De Siècle to the New Millennium. Tavistock, Devon, U.K: Northcote House. p. 5.

- ↑ Thacker, Deborah Cogan; Webb, Jean (2002). Introducing Children's Literature: From Romanticism to Postmodernism. London: Routledge. London: Routledge. p. 54.

- ↑ Popova, Maria. "I’m Glad I’m a Boy! I’m Glad I’m a Girl! "Boys fix things. Girls need things fixed."". brain pickings. brain pickings. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Kismaric, Carole; Heiferman, Marvin (1996). Growing up with Dick and Jane: Learning and Living the American Dream. San Francisco: Collins San Francisco,.

- ↑ Lurie, Alison (2003). Boys and Girls Forever: Reflections on Children's Classics. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 43 & 98.

- ↑ Lurie, Alison (2003). Boys and Girls Forever: Reflections on Children's Classics. London: Chatto & Windus. p. 82.

- ↑ Lurie, Alison (2003). Boys and Girls Forever: Reflections on Children's Classics. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 18–20, 25–45 & 82.

- ↑ Smith, Graham. "Pig-tailed Pippi Longstocking books branded 'racist' by German theologian". Mail Online. The Daily Mail. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Rao, Kavitha. "Are some children's classics unsuitable for kids?". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- 1 2 Marche, Stephen. "How to Read a Racist Book to Your Kids". The New York Times Magazine. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ McCorquodale, Duncan (December 29, 2009). Illustrated Children's Books. London: Black Dog Publishing. p. 78.

- ↑ Jenkins, Henry (1998). The Children's Cultural Reader. New York and London: New York University Press. pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Ha, Thu-Huong. "Spot the difference: This update to a classic children’s book reimagines gender roles". Quartz. Quartz. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ Jalongo, Mary Renck (2004). Young Children and Picture Books. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children. p. 17.

- ↑ Bettelheim, Bruno (2010). The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. United States: Vintage Books. p. 6.

- ↑ McCorquodale, Duncan (December 29, 2009). Illustrated Children's Books. London: Black Dog Publishing. p. 6.

- ↑ MacCann, Donnarae; Richard, Olga (1973). The child's first books; a critical study of pictures and texts. New York: Wilson. p. 1 & 107.

- ↑ Hunt, Peter (2003). Literature for Children Contemporary Criticism. London: Routledge. p. 18.

- ↑ Nodelman, Perry (2008). The Hidden Adult: Defining Children's Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins United Press. p. 100.

- ↑ Reynolds, Kimberley (2012). Children's Literature from the Fin De Siècle to the New Millennium. Tavistock, Devon, U.K: Northcote House. p. ix.

- ↑ Reynolds, Kimberley (2012). Children's Literature from the Fin De Siècle to the New Millennium. Tavistock, Devon, U.K: Northcote House. p. 4.

- 1 2 Reynolds, Kimberley (2012). Children's Literature from the Fin De Siècle to the New Millennium. Tavistock, Devon, U.K: Northcote House. p. 23.

- ↑ Egoff, Sheila A. (1981). Thursday's Child: Trends and Patterns in Contemporary Children's Literature. Chicago, Ill: American Library Association. p. 247.

- ↑ Trites, Roberta Seelinger (2000). Disturbing the Universe Power and Repression in Adolescent Literature. Iowa City: U of Iowa. p. xi-xii.

- ↑ Ausdale, Debra; Feagin, Joe R. (2001). The First R: How Children Learn Race and Racism. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield.

- ↑ Ausdale, Debra; Feagin, Joe R. (2001). The First R: How Children Learn Race and Racism. Lanham, Md: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 150–151.

- ↑ "Winners 2012: Fiction". Bologna Children's Book Fair. BolognaFiere S.p.A. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

Further reading

- Reynolds, Kimberley (2011). Children's Literature: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-956024-0.

- Zipes, Jack, ed. (2006). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514656-1.

- Anderson, Nancy (2006). Elementary Children's Literature. Boston: Pearson Education. ISBN 0-205-45229-9.

- Chapleau, Sebastien (2004). New Voices in Children's Literature Criticism. Lichfield: Pied Piper Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9546384-4-3.

- Huck, Charlotte (2001). Children's Literature in the Elementary School, 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-232228-4.

- Hunt, Peter (1991). Criticism, Theory, and Children's Literature. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-16231-3.

- Lesnik-Oberstein, Karin (1996). "Defining Children's Literature and Childhood". In Hunt, Peter (ed.). International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature. London: Routledge. pp. 17–31. ISBN 0-415-08856-9.

- Lesnik-Oberstein, Karin (1994). Children's Literature: Criticism and the Fictional Child. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-811998-4.

- Lesnik-Oberstein, Karin (2004). Children's Literature: New Approaches. Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 1-4039-1738-8.

- Rose, Jacqueline (1984). The Case of Peter Pan or the Impossibility of Children's Fiction (1993 ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1435-8.

- Wolf, Shelby (2010). Handbook of Research in Children's and Young Adult Literature. Cambridge: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96506-4.

External links

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Choosing High Quality Children's Literature |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Children's literature. |

| Library resources about Children's literature |

- International Board on Books for Young People

- National Children's Literacy Website, US-based literacy resource site

- Arne Nixon Center for the Study of Children's Literature at California State University, Fresno

- The Society of Children's Book Writers and Illustrators

- Children's Books Central

- International Companion Encyclopedia of Children's Literature.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Children's Literature.

- Francophone Children's Literature

- Series Books for Girls . . . and a Few for Boys

Digital Libraries

- International Children's Digital Library Repository of 2,827 children's books in 48 languages viewable over the Internet

- Digitized Children's Literature at the Library of Congress

- Children's Literature Research Collections at the University of Minnesota

- Baldwin Digital Library of Children's Literature

- Classics for Young People

- Children's eTexts at Project Gutenberg (more)

- Historic Children's Book Collection at Ball State University, Indiana – online access to children's books from the 20th and 19th centuries

- Childrens-Stories.net modern Children's Stories by leading authors available free online helping parent's and teachers encourage reading

|