Chewing gum

|

An unwrapped stick of chewing gum | |

| Type | Confectionery |

|---|---|

| Main ingredients | Chicle or polyisobutylene |

|

| |

Chewing gum is a soft, cohesive substance designed for chewing but not swallowing. Humans have used chewing gum in some form for at least 100,000 years. Modern chewing gum is made from butadiene-based synthetic rubber. Most chewing gums are considered polymers.

History

Chewing gum in many forms has existed since the Neolithic period. 5,000-year-old chewing gum made from birch bark tar, with tooth imprints, has been found in Kierikki, Yli-Ii, Finland. The tar from which the gums were made is believed to have antiseptic properties and other medicinal benefits.[1] The ancient Aztecs used chicle, a natural tree gum, as a base for making a gum-like substance and to stick objects together in everyday use. Forms of chewing gums were also chewed in Ancient Greece. The Ancient Greeks chewed mastic gum, made from the resin of the mastic tree.[2] Many other cultures have chewed gum-like substances made from plants, grasses, and resins.

The American Indians chewed resin made from the sap of spruce trees.[3] The New England settlers picked up this practice, and in 1848, John B. Curtis developed and sold the first commercial chewing gum called The State of Maine Pure Spruce Gum. Around 1850 a gum made from paraffin wax was developed and soon exceeded the spruce gum in popularity. William Semple filed an early patent on chewing gum, patent number 98,304, on December 28, 1869.[4]

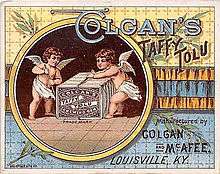

The first flavored chewing gum was created in the 1860s by John Colgan, a Louisville, Kentucky pharmacist. Colgan mixed the aromatic flavoring tolu, a powder obtained from an extract of the balsam tree with powdered sugar, creating small sticks of flavored chewing gum he named "Taffy Tolu".[5] Colgan also lead the way in the manufacturing and packaging of chicle-based chewing gum, licensing a patent for automatically cutting chips of chewing gum from larger sticks: US 966,160 "Chewing Gum Chip Forming Machine" August 2, 1910[6] and a patent for automatically cutting wrappers for sticks of chewing gum: US 913,352 "Web-cutting attachment for wrapping-machines" February, 23, 1909[7] from Louisville, Kentucky inventor James Henry Brady, an employee of the Colgan Gum Company.

Modern chewing gum was first developed in the 1860s when chicle was brought from Mexico by the former President, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, to New York, where he gave it to Thomas Adams for use as a rubber substitute. Chicle did not succeed as a replacement for rubber, but as a gum, which was cut into strips and marketed as Adams New York Chewing Gum in 1871.[8] Black Jack (1884) and Chiclets (1899), it soon dominated the market.[9] Synthetic gums were first introduced to the U.S. after chicle no longer satisfied the needs of making good chewing gum. The hydrocarbon polymers approved to be in chewing gum are styrene-butadiene rubber, isobutylene, isoprene copolymer, paraffin wax, and petroleum wax. By the 1960s, US manufacturers had switched to butadiene-based synthetic rubber, as it was cheaper to manufacture.

Effects on health

Brain function

A review about the cognitive advantages of chewing gum by Onyper et al. (2011) found strong evidence of improvement for the following cognitive domains: Working memory, episodic memory and perceptual speed of processing. However the improvements were only evident when chewing took place prior to cognitive testing. The precise mechanism by which gum chewing improves cognitive functioning is however not well understood. The researchers did also note that chewing-induced arousal could be masked by the distracting nature of chewing itself, which they named "dual-process theory", which in turn could explain some of the contradictory findings by previous studies. They also noticed the similarity between mild physical exercise such as pedaling a stationary bike and chewing gum. It has been demonstrated that mild physical exercise leads to little cognitive impairment during the physical task accompanied by enhanced cognitive functioning afterwards. Furthermore, the researchers noted that no improvement could be found for verbal fluency, which is in accordance with previous studies. This finding suggests that the effect of chewing gum is domain specific. The cognitive improvements after a period of chewing gum have been demonstrated to last for 15–20 minutes and decline afterwards.[10]

Dental health

Sugar-free gum sweetened with xylitol has been shown to reduce cavities and plaque.[11] The sweetener sorbitol has the same benefit, but is only about one-third as effective as xylitol.[11] Other sugar substitutes, such as maltitol, aspartame and acesulfam, have also been found to not cause tooth decay.[8][12] Xylitol is specific in its inhibition of Streptococcus mutans, bacteria that are significant contributors to tooth decay.[13] Xylitol inhibits Streptococcus mutans in the presence of other sugars, with the exception of fructose.[14] Xylitol is a safe sweetener that benefits teeth and saliva production because it is not fermented to acid like most sugars.[8] Daily doses of xylitol below 3.44 grams are ineffective and doses above 10.32 grams show no additional benefit.[13] Other active ingredients in chewing gum include fluoride, which strengthens tooth enamel, and p-chlorbenzyl-4-methylbenzylpiperazine, which prevents travel sickness. Chewing gum also increases saliva production.[8]

Food and sucrose have a demineralizing effect upon enamel that has been reduced by adding calcium lactate to food.[15] Calcium lactate added to toothpaste has reduced calculus formation.[16] One study has shown that calcium lactate enhances enamel remineralization when added to xylitol-containing gum,[17] but another study showed no additional remineralization benefit from calcium lactate or other calcium compounds in chewing-gum.[18]

Other studies[19] indicated that the caries preventive effect of chewing sugar-free gum is related to the chewing process itself rather than being an effect of gum sweeteners or additives, such as polyols and carbamide.

A helpful way to cure halitosis (bad breath) is to chew gum. Chewing gum not only helps to add freshness to breath but can aid in removing food particles and bacteria associated with bad breath from teeth. It does this by stimulating saliva, which essentially washes out the mouth. Chewing sugar-free gum for 20 minutes after a meal helps prevent tooth decay, according to the American Dental Association, because the act of chewing the sugar-free gum produces saliva to wash away bacteria, which protects teeth.[20] Chewing gum after a meal replaces brushing and flossing, if that's not possible, to prevent tooth decay and increase saliva production.[21] Chewing gum can also help with the lack of saliva or xerostomia since it naturally stimulates saliva production.[8] Saliva is made of chemicals, such as organic molecules, inorganic ions and macromolecules. 0.5% of saliva deals with dental health, since tooth enamel is made of calcium phosphate, those inorganic ions in saliva help repair the teeth and keep them in good condition. The pH of saliva is neutral, which having a pH of 7 allows it to remineralize tooth enamel. Falling below a pH of 5.5 (which is acidic) causes the saliva to demineralize the teeth.[8]

Masumoto et al. looked at the effects of chewing gum after meals following an orthodontic procedure, to see if chewing exercises caused subjects pain or discomfort, or helped maintain a large occlusal contact area. 35 adult volunteers chewed gum for 10 to 15 minutes before or after three meals each day for 4 weeks. 90% of those questioned said that the gum felt "quite hard", and half reported no discomfort.[22]

Use in surgery

Several randomized controlled studies have investigated the use of chewing gum in reducing the duration of post-operative ileus following abdominal and specifically gastrointestinal surgery. A systematic review of these suggests gum chewing, as a form of "sham feeding", is a useful treatment therapy in open abdominal or pelvic surgery, although the benefit is less clear when laparoscopic surgical techniques are used.[23]

Chewing gum after a colon surgery helps the patient recover sooner. If the patient chews gum for fifteen minutes for at least four times per day, it will reduce their recovery time by a day and a half.[24] The average patient took 0.66 fewer days to pass gas and 1.10 fewer days to have a bowel movement.[25] Saliva flow and production is stimulated when gum is chewed. Gum also gets digestive juices flowing and is considered "sham feeding".[25] Sham feeding is the role of the central nervous system in the regulation of gastric secretion.

Stomach

Chewing gum is used as a novel approach for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). One hypothesis is that chewing gum stimulates the production of more bicarbonate-containing saliva and increases the rate of swallowing. After the saliva is swallowed, it neutralizes acid in the esophagus. In effect, chewing gum exaggerates one of the normal processes that neutralize acid in the esophagus.[26] However, chewing gum is sometimes considered to contribute to the development of stomach ulcers. It stimulates the stomach to secrete acid and the pancreas to produce digestive enzymes that aren't required.[27] In some cases, when consuming large quantities of gum containing sorbitol, gas and/or diarrhea may occur.

Possible carcinogens

Concern has arisen about the possible carcinogenicity of the vinyl acetate (acetic acid ethenyl ester) used by some manufacturers in their gum bases. Currently, the ingredient can be hidden in the catch-all term "gum base". The Canadian government at one point classified the ingredient as a "potentially high hazard substance."[28] However, on January 31, 2009, the Government of Canada's final assessment concluded that exposure to vinyl acetate is not considered to be harmful to human health.[29] This decision under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) was based on new information received during the public comment period, as well as more recent information from the risk assessment conducted by the European Union.

Swallowed gum

Various myths hold that swallowed gum will remain in a human's stomach for up to 7 years, as it is not digestible. According to several medical opinions, there seems to be little truth behind the tale. In most cases, swallowed gum will pass through the system as quickly as any other food.[30]

There have been cases where swallowing gum has resulted in complications requiring medical attention. A 1998 paper describes a four-year-old boy being referred with a two-year history of constipation. The boy was found to have "always swallowed his gum after chewing five to seven pieces each day", being given the gum as a reward for good behavior, and the build-up resulted in a solid mass which could not leave the body.[31] A 1½-year-old girl required medical attention when she swallowed her gum and four coins, which got stuck together in her esophagus.[30][31] A bezoar is formed in the stomach when food or other foreign objects stick to gum and build up, causing intestinal blockage.[32] As long as the mass of gum is small enough to pass out of the stomach, it will likely pass out of the body easily,[33] but it is recommended that gum not be swallowed or given to young children who do not understand not to.[31]

Bans

Many schools do not allow chewing gum because students often dispose of it inappropriately, the chewing may be distracting in class, and the gum might carry diseases or bacteria from other students.[34]

The Singapore government outlawed chewing gum in 1992 citing the danger of discarded gum being wedged in the sliding doors of underground trains. However, in 2002 the government allowed sugarless gum to be sold in pharmacies if a doctor or dentist prescribed it.[8]

Detrimental effects on the environment

Chewing gum is not water-soluble and unlike other confectionery is not fully consumed. There has been much effort at public education and investment aimed at encouraging responsible disposal. Despite this it is commonly found stuck underneath benches, tables, handrails and escalators. It is extremely difficult and expensive to remove once "walked in" and dried. Gum bonds strongly to asphalt and rubber shoe soles because they are all made from polymeric hydrocarbons. It also bonds strongly with concrete paving. Removal is generally achieved by steam jet and scraper but the process is slow and labour-intensive.

Most external urban areas with high pedestrian traffic show high incidence of casual chewing gum discard. Likely as a consequence of Singapore's ban, Singapore's pavements are, perhaps uniquely amongst modern cities, free of gum. More than other litter which can be picked up or is quickly degraded by the weather, chewing gum, with its glue-like characteristics, is regarded as environmentally damaging. In 2000 a study on Oxford Street, one of London’s busiest shopping streets, showed that a quarter of a million black or white blobs of chewing gum were stuck to its pavement.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ "Student dig unearths ancient gum" BBC.co.uk.

- ↑ "The History of Chewing Gum and Bubble Gum" page of About.com Inventors.

- ↑ "History Of Chewing Gum" page of BeemarsGum.org.

- ↑ Patent number 98,304

- ↑ "It's Flavored Chewing Gum: Taffy Tolu Invention Is Remembered". Kentucky New Era (Hopkinsville, Christian County, Kentucky). December 22, 1978. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Web-cutting attachment for wrapping-machines". Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- ↑ "Web-cutting attachment for wrapping-machines". Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Emsley, J. (2004). Vanity, vitality, and virility. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 189–97. ISBN 0-19-280509-6.

- ↑ Chewing gum companies in 1860-1900

- ↑ Onyper, Serge V.; Carr, Timothy L.; Farrar, John S.; Floyd, Brittney R. (2011). "Cognitive advantages of chewing gum. Now you see them, now you don't". Appetite 57 (2): 321–8. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2011.05.313. PMID 21645566.

- 1 2 Deshpande, Amol; Jadad, Alejandro R. (2008). "The impact of polyol-containing chewing gums on dental caries". The Journal of the American Dental Association 139 (12): 1602–14. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0102. PMID 19047666.

- ↑ Thabuis, C; Cheng, C. Y.; Wang, X; Pochat, M; Han, A; Miller, L; Wils, D; Guerin-Deremaux, L (2013). "Effects of maltitol and xylitol chewing-gums on parameters involved in dental caries development". European Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 14 (4): 303–8. PMID 24313583.

- 1 2 Milgrom, P.; Ly, K.A.; Roberts, M.C.; Rothen, M.; Mueller, G.; Yamaguchi, D.K. (2006). "Mutans Streptococci Dose Response to Xylitol Chewing Gum". Journal of Dental Research 85 (2): 177–81. doi:10.1177/154405910608500212. PMC 2225984. PMID 16434738.

- ↑ Kakuta, Hatsue; Iwami, Yoshimichi; Mayanagi, Hideaki; Takahashi, Nobuhiro (2003). "Xylitol Inhibition of Acid Production and Growth of Mutans Streptococci in the Presence of Various Dietary Sugars under Strictly Anaerobic Conditions". Caries Research 37 (6): 404–9. doi:10.1159/000073391. PMID 14571117.

- ↑ Kashket, S.; Yaskell, T. (1997). "Effectiveness of Calcium Lactate Added to Food in Reducing Intraoral Demineralization of Enamel". Caries Research 31 (6): 429–33. doi:10.1159/000262434. PMID 9353582.

- ↑ Schaeken, M.J.M.; Van Der Hoeven, J.S. (1993). "Control of Calculus Formation by a Dentifrice Containing Calcium Lactate". Caries Research 27 (4): 277–9. doi:10.1159/000261550. PMID 8402801.

- ↑ Suda, R.; Suzuki, T.; Takiguchi, R.; Egawa, K.; Sano, T.; Hasegawa, K. (2006). "The Effect of Adding Calcium Lactate to Xylitol Chewing Gum on Remineralization of Enamel Lesions". Caries Research 40 (1): 43–6. doi:10.1159/000088905. PMID 16352880.

- ↑ Schirrmeister, J.F.; Seger, R.K.; Altenburger, M.J.; Lussi, A.; Hellwig, E. (2007). "Effects of Various Forms of Calcium Added to Chewing Gum on Initial Enamel Carious Lesions in situ". Caries Research 41 (2): 108. doi:10.1159/000098043. PMID 17284911.

- ↑ Machiulskiene, Vita; Nyvad, Bente; Baelum, Vibeke (2001). "Caries preventive effect of sugar-substituted chewing gum". Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 29 (4): 278–88. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290407.x. PMID 11515642.

- ↑ Gajilan, Chris. "Chew on this: Gum may be good for body, mind". CNN. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ↑ Sioda, Paul. "Can I Chew Gum?". Paul Sioda Dentistry. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ↑ Masumoto, N.; Yamaguchi, K.; Fujimoto, S. (2009). "Daily chewing gum exercise for stabilizing the vertical occlusion". Journal of Oral Rehabilitation 36 (12): 857–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2009.02010.x. PMID 19845836.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, J. Edward F.; Ahmed, Irfan (2009). "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Chewing-Gum Therapy in the Reduction of Postoperative Paralytic Ileus Following Gastrointestinal Surgery". World Journal of Surgery 33 (12): 2557–66. doi:10.1007/s00268-009-0104-5. PMID 19763686.

- ↑ Abd-El-Maeboud, KHI; Ibrahim, MI; Shalaby, DAA; Fikry, MF (2009). "Gum chewing stimulates early return of bowel motility after caesarean section". BJOG 116 (10): 1334–9. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02225.x. PMID 19523094. Lay summary – Rodale (September 2, 2009).

- 1 2 Purkayastha, Sanjay; Tilney, H. S.; Darzi, A. W.; Tekkis, P. P. (2008). "Meta-analysis of Randomized Studies Evaluating Chewing Gum to Enhance Postoperative Recovery Following Colectomy". Archives of Surgery 143 (8): 788–93. doi:10.1001/archsurg.143.8.788. PMID 18711040. Lay summary – Science Daily (August 19, 2008).

- ↑ Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

- ↑ "Risky chewing gum, gum, gum". Janethull.com. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ↑ "Substance found in chewing gum could be labelled toxic". Canada.com. 2008-05-30. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- ↑ "Summary of Public Comments Received on the Government of Canada's Draft Screening Assessment Report and Risk Management Scope on Bisphenol A" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- 1 2 Matson, John. "Fact or Fiction?: Chewing Gum Takes Seven Years to Digest: Scientific American". Sciam.com. Retrieved 2012-01-25.

- 1 2 3 Milov, D. E.; Andres, J. M.; Erhart, N. A.; Bailey, D. J. (1998). "Chewing Gum Bezoars of the Gastrointestinal Tract". Pediatrics 102 (2): e22. doi:10.1542/peds.102.2.e22. PMID 9685468.

- ↑ Rimar, Yossi; Babich, Jay P; Shaoul, Ron (2004). "Chewing gum bezoar". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 59 (7): 872. doi:10.1016/S0016-5107(04)00162-2. PMID 15173807.

- ↑ "...eventually the normal housekeeping waves in the digestive tract will sort of push it through, and it will come out pretty unmolested."

- ↑ "B-schools ban chewing gum on campus". indiatimes.com. 26 June 2009. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

-solution.jpg)