Chest pain in children

| Pediatric chest pain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Classification and external resources | |

| ICD-10 | R07 |

| ICD-9-CM | 786.5 |

| DiseasesDB | 16537 |

| MedlinePlus | 003079 |

| MeSH | D002637 |

Chest pain in children is the pain felt in the chest by infants, children and adolescents. In most cases the pain is not associated with the heart. It is primarily identified by the observance or report of pain by the infant, child or adolescent by reports of distress by parents or caregivers. Chest pain is not uncommon in children. Many children are seen in ambulatory clinics, emergency departments and hospitals and cardiology clinics. Most often there is a benign cause for the pain for most children. Some have conditions that are serious and possibly life-threatening. Chest pain in pediatric patients requires careful physical examination and a detailed history that would indicate the possibility of a serious cause. Studies of pediatric chest pain are sparse and prospective studies remain largely unavailable. It has been difficult to create evidence-based guidelines for evaluation.[1]

Differential diagnosis

Chest pain in children is usually evaluated in cardiology clinics and in emergency room departments. It can be distressing for parents and children. Pediatric chest pain differs from chest pain in adults because it is most often unrelated to the heart.[2] The causes of pediatric chest pain vary according to the organ or tissue in the child. that generates the pain. Generally, muscular skeletal pain, which includes costochondritis, is the reason for the emergency room visit. Pain that is felt in the chest but is due to muscular skeletal inflammation or an unknown cause and accounts for 7% and 69% visits. Muscular skeletal pain is described and defined differently as a diagnosis of exclusion or is documented as being associated with idiopathic causes. Asthma and other respiratory symptoms are the second most common presentation. Respiratory associated causes compose 13% to 24% of pediatric chest pain symptoms. Gastrointestinal and psychogenic symptoms reported by parents and patients occur less than 10% of the time. Cardiac causes of pediatric chest pain are found infrequently and are not identified more than 5% of the time. Unknown causes, were estimated to account for 20% to 61% of the final diagnosis given. Patients who receive a diagnosis of cardiac disease are more apt to have acute pain. This pain often awakes them from sleep or presents with fever or abnormal observations found during the physical examination. Trauma can also be a cause for chest pain and has been found to be associated with the pain in 5% of the patients.[1]

Children can present with chest pain can have a sudden onset related to vigorous physical activity and coughing. These symptoms seem to be closely associated with asthma.[1] Infection with Haemophilus influenzae can cause chest pain.[3]

Preliminary

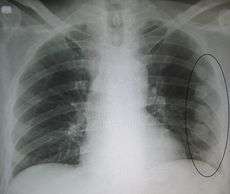

Since most causes of pediatric and adolescent chest pain are not considered life-threatening, parents and their children are often reassured that in the majority of cases, the cause of the pain can be determined. If the child or adolescent appears to have some dehydration, and intravenous line along with administration of saline is done. The clinician may or may not decide to perform diagnostic testing . This is especially true if the child or adolescent has symptoms of chronic pain. If an obvious cause of the chest pain is not readily apparent, testing may begin with an x-rayand an electrocardiogram . This helps the clinician to determine whether or not the cause of pain is related to pulmonary or cardiac causes.[4]

A possible preliminary diagnosis may be able to made based upon consistent symptoms. Some of these are:

- bruising and chest pain could be from unrecognized trauma

- an abnormal abdominal examination may be related to a possible gastrointestinal condition with pain referred to the chest.

- abnormal blood pressure measurements suggests to the clinician that dehydration may be present and related to cardiac insufficiency

- heart sounds such as heart murmur, rub, arrhythmia may indicate to a condition of the heart

- the pain may be related to a chronic illness and may be part of a serious condition such as systemic lupus erythematosus or Hodgkin lymphoma [5]

- pleural effusion and chest pain may be related to arthritis

- decreased breath sounds or wheezing can be suggestive of asthma or the fatigue of chest wall muscles

- subcutaneous emphysema can be felt by the clinician indicating a pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax

- tenderness of the costochondral junctions or the wall of the chest is suggestive of musculoskeletal or costochondritis pain[4]

Cardiac associated risks

.png)

Preliminary "red flags" are identified that are more likely to suggest chest pain associated with heart. These are:

- past or current history of congentital or acquired heart disease

- fainting when the child exerts herself or himself

- an abnormality of blood coagulation that increases the risk of blood clots

- high levels of cholesterol in the blood

- history of:

- the sudden death of a family member under 35 years-old

- the early onset in a family member of coronary artery disease

- an family history arrhythmias such as Brugada syndrome or Long QT syndrome

- an implanted cardioverter defibrillator

- having a connective tissue disease

- a history of cocaine/amphetamine use[2]

Testing

If the diagnosis is unclear, the clinician may order additional testing. These tests may be an electrocardiogram, stress test, pulmonary function test, drug screen and ultrasound.[4][6]

Muscular skeletal causes

Respiratory causes

- asthma[1][4]

- airway foreign body[1]

- chronic cough[4]

- Coxsackievirus

- Pleural effusion[1]

- Pneumonia[4]

- pulmonary embolism

- pleuritis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus[1]

- Pleural effusion[4]

Cardiovascular causes

- Coronary artery disease

- Kawasaki disease

- Premature arterial sclerosis

- Structural associations

- Arterial vasospasm

- Cocaine/marijuana toxicity and induced vasospasm

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Valvular stenosis

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Aortic aneurysm or dissection

- Noonan, Turner, or Marfan syndromes

- Congenital absence of pericardium

- Endocarditis

- Pericarditis[10]

- Pneumothorax

- Myocarditis

- Arrhythmia[1]

- Rhythm disturbances

- Ischemia[4]

Gastrointestinal causes

Non-organic causes

Epidemiology

Chest pain is relatively common in children and adolescents. Unlike adults, the cause is rarely cardiac.[2] Approximately 0.3% to 0.6% of emergency room department visits by pediatric patients are for chest pain. The emergency department visits are consistent throughout the seasons and times of year. The median age pediatric patients that complain of pain is from 12 to 13 years old both males and females display the symptoms and signs at approximately the same ratio.[2] Those that do complain of the chest pain usually present with acute pain that they have experienced for less than one day. This is not universal though. A small study in Turkey evaluated patients and found that 59% complained of pain that they had had for more than one month in duration. Estimates of 13% to 24% of patients seen in the emergency department are found to have a pulmonary association with their pain.[1]

Treatment

Children who have chest pain that is related to asthma and exercise stress can be treated with bronchodilator use.[1] If there is obviously distress and difficulty breathing, treatment to provide the support of airway and breathing is provided. In addition, treatment can include measures to support circulation.[4]

Part of effective treatment includes obtaining a detailed medical history .[2] A medical history taken by the clinician covers the following topics:

- past medical history

- history of trauma

- recent use of cocaine

- a description of the pain

- the presence of nausea , vomiting , and anorexia

- shortness of breath and pain worse with exertion .

- the time of the onset of pain

- family history

- dizziness

- severity and frequency of pain

- recent significant stress (examples: death of a loved one, moving to a new home, serious illness in the family)

- possible associated complaints[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Thull-Freedman, Jennifer (2010). "Evaluation of Chest Pain in the Pediatric Patient". Medical Clinics of North America 94 (2): 327–347. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2010.01.004. ISSN 0025-7125. PMID 20380959: Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Collins, S. A.; Griksaitis, M. J.; Legg, J. P. (2013). "15-minute consultation: A structured approach to the assessment of chest pain in a child" (PDF). Archives of Disease in Childhood - Education and Practice 99 (4): 122–126. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-303919. ISSN 1743-0585.

- ↑ Yeh, Y-H; Chu, P-H; Yeh, C-H; Jan Wu, Y-J; Lee, M-H.; Jung, S-M; Kuo, C-T (2004). "Haemophilus influenzae pericarditis with tamponade as the initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus". International Journal of Clinical Practice 58 (11): 1045–1047. doi:10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00041.x. ISSN 1368-5031. PMID 15605669.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 McMahon, Maureen (2011). Pediatrics a competency-based companion. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-5350-7: Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

- ↑ Maharaj, Satish S; Chang, Simone M (2015). "Cardiac tamponade as the initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus: a case report and review of the literature". Pediatric Rheumatology 13 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/s12969-015-0005-0. ISSN 1546-0096.

- ↑ Brass, Patrick; Hellmich, Martin; Kolodziej, Laurentius; Schick, Guido; Smith, Andrew F; Brass, Patrick (2015). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011447.

|chapter=ignored (help) - ↑ Keech, Brian M. (2015). "Thoracic epidural analgesia in a child with multiple traumatic rib fractures". Journal of Clinical Anesthesia 27 (8): 685–691. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2015.05.008. ISSN 0952-8180. PMID 26118312.

- ↑ Bounakis, Nikolaos; Karampalis, Christos; Sharp, Hilary; Tsirikos, Athanasios I (2015). "Surgical treatment of scoliosis in Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome type 2: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports 9 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-9-10. ISSN 1752-1947.

- ↑ Stroud, Andrea M.; Tulanont, Darena D.; Coates, Thomasena E.; Goodney, Philip P.; Croitoru, Daniel P. (2014). "Epidural analgesia versus intravenous patient-controlled analgesia following minimally invasive pectus excavatum repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Pediatric Surgery 49 (5): 798–806. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.02.072. ISSN 0022-3468. PMID 24851774.

- ↑ Punja, Mohan; Mark, Dustin G.; McCoy, Jonathan V.; Javan, Ramin; Pines, Jesse M.; Brady, William (2010). "Electrocardiographic manifestations of cardiac infectious-inflammatory disorders". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 28 (3): 364–377. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2008.12.017. ISSN 0735-6757. PMID 20223398:Access provided by the University of Pittsburgh

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||