Chera dynasty

| Chera kingdom | |||||

| Monarchy | |||||

| |||||

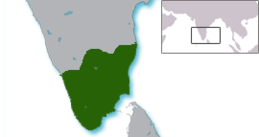

Extent of Chera kingdom | |||||

| Capital | Early Cheras: Karuvur Later/ Second Cheras: Mahodayapuram | ||||

| Languages | Tamil, Malayalam[1] | ||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||

| Political structure | Monarchy | ||||

| History | |||||

| • | Established | c. 3rd century BCE | |||

| • | Disestablished | 10th century CE (1124, 2nd Chera kingdom) | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

| Part of a series on |

| History of Tamil Nadu |

|---|

|

| Outline of South Asian history | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Riwatian people (1,900,000 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Soanian people (500,000 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Stone Age (50,000–3000 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bronze Age (3000–1300 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Iron Age (1200–230 BCE)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Classical period (230 BCE–1279CE) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late medieval period (1206–1596)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern period (1526–1858)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Colonial period (1510–1961)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other states (1102–1947)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Kingdoms of Sri Lanka

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nation histories |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Cheras, also known as Keralaputras,[2] were an ancient Dravidian dynasty of Tamil origin, who ruled parts of the present-day Tamil Nadu and Kerala state in India.[3] Together with the Chola and the Pandyas, it formed the three principal warring Iron Age kingdoms of South India, known as Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam, in the early centuries of the Common Era.

By the early centuries of the Common Era, civil society and statehood under the Cheras were developed in present-day western Tamil Nadu. The location of the Chera capital is generally assumed to be at modern Karur (identified with the Korura of Ptolemy). The Chera kingdom later extended to the plains of Kerala, the Palghat gap, along the river Perar and occupied land between the river Perar and river Periyar, creating two harbor towns, Tondi (Tyndis) and Muciri (Muziris),[4][5] where the Roman trade settlements flourished.[6]

The Cheras were in continuous conflict with the neighbouring Cholas and Pandyas. The Cheras are said to have defeated the combined armies of the Pandyas and the Cholas and their ally states. They also made battles with the Kadambās of Banavasi and the Yavanas (the Greeks) on the Indian coast. After the 2nd century CE, the Cheras' power decayed rapidly with the decline of the lucrative trade with the Romans.[7]

The Tamil poetic collection called Sangam literature describes a long line of Chera rulers dated to the first few centuries CE. It records the names of the kings, the princes, and the court poets who extolled them. The internal chronology of this literature is still far from settled, and at present a connected account of the history of the period cannot be derived. Uthiyan Cheralathan, Nedum Cheralathan and Senguttuvan Chera are some of the rulers referred to in the Sangam poems. Senguttuvan Chera, the most celebrated Chera king, is famous for the legends surrounding Kannagi, the heroine of the Tamil epic Silapathikaram.[8]

The Chera kingdom owed its importance to trade with West Asia, Greece and Rome. Its geographical advantages, like the abundance of exotic spices, the navigability of the rivers connecting the Ghat mountains with the Arabian sea, and the discovery of favourable Monsoon winds which carried sailing ships directly from the Arabian coast to Chera kingdom, combined to produce a veritable boom in the Chera foreign trade.[7]

The Later Cheras ruled from the 9th century. Little is known about the Cheras between the two dynasties. The second dynasty, Kulasekharas ruled from a city on the banks of River Periyar called Mahodayapuram (Kodungallur).[9] Though never regained the old status in the Peninsula, Kulasekharas fought numerous wars with their powerful neighbors and diminished to history in the 12th century as a result of continuous Chola and Rashtrakuta invasions. The Chera dynasty was supported by Tamil warriors such as Villavar, Vanavar and Malayar clans.

The Chera rulers of Venadu, based at the port Quilon in southern Kerala, trace their relations back to the later/second Cheras. Ravi Varma Kulasekhara, ruler of Venadu from 1299 to 1314, is known for his ambitious military campaigns to former Pandya and Chola territories.[10]

Etymology of the word Chera

The word Chera probably derived from Cheral, meaning "declivity of a mountain" in ancient Tamil.[11][12][13] The Cheras are referred as Kedalaputho ("Kerala Putra") in the Ashoka's edicts (3rd century BCE).[14] The Graeco-Roman trade map Periplus Maris Erythraei refers the Cheras as Celobotra.[15]

The term Ceralamdivu or Ceran tivu and its cognates, meaning the "island of the Ceran kings", is a Classical Tamil name of Sri Lanka that takes root from the term Chera, from which the dynasty name is derived.[16]

Early Cheras

Indian literary sources

The primary literary sources available regarding the early Chera Kings are the anthologies of Sangam literature, created between c. 1st and the 4th centuries CE.[17][18] Pathirruppaththu, the fourth book in the Ettuthokai anthology of Sangam poems, mentions a number of rulers of the Chera dynasty. Each ruler is praised in ten songs sung by the court poet. The rulers (many were heirs-apparent) are mentioned in the following order:[19]

- Nedum Cheralathan – Kumatturk Kannanar

- Palyane Chel Kezhu Kuttuvan -Palaik Kantamanar

- Narmudi Cheral – Kappiyarruk Kappiyanar

- Senguttuvan Chera – Paranar

- Adu Kottu Pattu Cheralathan – Kakkaipatiniyar Nacellaiyar

- Selva Kadumko Valiathan – Kapilar

- Perum Cheral Irumporai – Aricil Kilar

- Ilam Cheral Irumporai – Perunkunrurk Kilar

Sangam literature is rich in descriptions about a number of Chera kings and princes, along with the poets who extolled them. However, these are not worked into connected history and settled chronology so far.[20] A chronological device, known as Gajabahu synchronism, is used by historians to help date early Tamil history.[21] Despite its dependency on numerous conjectures, Gajabahu synchronism has wide acceptance among modern scholars and is considered as the sheet anchor for the purpose of dating ancient Tamil literature.[22][23] The method depends on an event depicted in Silappatikaram, which describes the visit of Kayavaku, the king of Ilankai (Sri Lanka), in the Chera kingdom during the reign of the Chera king, Senguttuvan. The Gajabahu method considers this Kayavaku as Gajabahu, who according Mahavamsa, a historical poem written in Pali language on the kings of Sri Lanka, lived in the latter half of the 2nd century CE. This, in turn, has been used to fix the period Senguttuvan, who ruled his kingdom for 55 years (according to the Pathirruppaththu), in the 2nd century CE.[24]

The Cheras, the Pandyas, and the Cholas are also mentioned as the three ruling dynasties of Southern India in the Hindu epic Ramayana.[25][26] Cheras are also mentioned in Aitareya Aranyaka, and Mahabharata, where they take the sides with the Pandavas in the famous war at Kurukshetra.[27][28]

Archaeological sources

Archaeology has found epigraphic evidence of the early Cheras.[29] Two identical inscriptions near Tiruchirappalli, dated to the 2nd century CE, describe three generations of Chera rulers of the Irumporai clan. They record the construction of a rock shelter for Jains on the occasion of the investiture of the crown prince Ilam Kadungo, son of Perum Kadungo, and the grandson of Athan Cheral Irumporai.

Rulers according to the Sangam poems

Uthiyan Cheralathan

The first of the known rulers of the Chera entity was "Vanavaramban" Perumchottu Uthiyan Cheralathan. His capital was at Kuzhumur. Uthiyan Cheralathan was a contemporary of the Chola ruler Karikala Chola. Mamulanar credits him with having conducted a feast in honour of his ancestors. In a battle at Venni, Uthiyan Cheralathan was wounded on the back by Karikala Chola (Pattinappalai ). Unable to bear the disgrace, the Chera committed suicide by starvation.[19][30]

Nedum Cheralathan

Nedum Cheralathan probably consolidated the Chera kingdom, and literature and art developed highly during his period. Nedum Cheralathan is praised in the Second Ten of Pathirruppaththu composed by his court poet Kannanar. Nedum Cheralathan, famous for his hospitality, even gave a part of Umbarkkattu (Anamalai) to Kannanar.[11]

The greatest enemies of Nedum Cheralathan were Kadambas of Banavasi. He also won another victory over the Yavanas (Westerners) on the coast. The chief of the Yavanas was captured and paraded in public with hands pinioned to his back and head poured over with ghee. Mamulanar refers to a sea coast township called Mantai and the exhibition ornaments and diamonds captured by Nedum Cheralathan there. Nedum Cheralathan was killed in a battle with a Chola ruler. The Chola ruler was also killed in the battle by a spear thrown at him by Nedum Cheralathan.[11]

Nedum Cheralathan is claimed to have conquered Bharatavarsha up to the Himalayas and to have inscribed his royal emblem on the face of the mountains.

Palyani Sel Kelu Kuttuvan

"Puzhiyarkon" Palyani Sel Kelu Kuttuvan was the brother of Nedum Cheralathan. He helped his brother in the conquests of northern Malabar. At least a part of northern Malabar came under the Chera rule in this period as is proven by the title "Puzhiyarkon". In the later years of his life, Palyani retired from military life and spent time in arts, letters, gifts and helping Brahmins.[11]

Narmudi Cheral

"Kalangaikkani" Narmudi Cheral (son of Nedum Cheralthan) is praised in the 4th set, written by Kappiyanar. He, famous for his generosity over the defeated, won a series of victories of the enemies. In the battle of Vakai-perum-turai Narmudi Cheral defeated and killed Nannan of Ezhimalai, annexing Puzhinadu.[11]

Selva Kadumko Valiathan

Selva Kadumko Valiathan was the son of Anthuvan Cheral and the hero of the 7th set of poems composed by Kapilar. His residence was at the city of Tondi. He married the sister of the wife of Nedum Cheralathan. Selva Kadumko defeated the combined armies of the Pandyas and the Cholas. He is sometimes identified as the Athan Cheral Irumporai mentioned in the Aranattar-malai inscription of Pugalur.[11]

Vel Kelu Kuttuvan (Senguttuvan)

Vel Kelu Kuttuvan, son of Nedum Cheralathan, ascended to the Chera throne after the death of his father. Vel Kelu Kuttuvan is often identified with the legendary Kadal Pirakottiya "Senguttuvan Chera", the most illustrious ruler of the early Cheras of the Sangam Age. Under his reign, the Chera kingdom extended from Kollimalai in the east to Tondi and Mantai on the western coast. The queen of Senguttuvan was Illango Venmal (the daughter of a Velir chief).[11]

In the early years of his rule, Senguttuvan successfully intervened in a civil war in the Chola Kingdom. The war was among the Chola princes and the Cheras stood on the side of their relative Killi. The rivals of Prince Killi were defeated in a battle at Neriyavil, Uraiyur and he firmly established the Chola throne.

The land and naval expedition against the Kadambas was also successful. The Kadambas had the support of the Yavanas, who were routed in the Battle of Idumbil and Valyur. The Fort Kodukur in the which the Kadamba army took shelter was stormed and the Kadambas was beaten. In the following naval expedition the Yavana-supported Kadamba army was crushed. He is said to have defeated the Kongu people and a warrior called Mogur Mannan.

Ilango Adigal wrote the legendary Tamil epic Silappatikaram, which describes his brother Senguttuvan Chera's decision to propitiate a temple (Virakkallu) for the goddess Pattini (Kannagi) at Vanchi.

Senguttuvan Chera was perhaps a contemporary king Gajabahu of Sri Lanka. King Gajabahu, according to the Sangam poems, visited the Chera country during the Pattini festival at Vanchi.[31] He is mentioned in the context of king Gajabahu’s rule in Sri Lanka, which can be dated to either the first or last quarter of the 2nd century CE, depending on whether he was the earlier or the later Gajabahu.[8]

Adu Kottu Pattu Cheralathan

Adu Kottu Pattu Cheralathan was a crown prince for a long 38 years. Trade and commerce flourished in the Chera kingdom during his rule. He is said to have given some villages to Brahmins in Kuttanadu.[11]

Perum Cheral Irumporai

"Tagadur Erinta" Perum Cheral Irumporai defeated the combined armies of the Pandyas, Cholas and that of the chief of Tagadur. He destroyed the famous city of Tagadur which was ruled by the a powerful ruler Adigaman Ezhni. He is also called "the lord of Puzhinad and Kollimala" and "the lord of Puhar". Puhar was the Chola capital. Perum Cheral Irumporai also annexed the territories of a minor chief called Kaluval.[11]

Illam Cheral Irumporai

Illam Cheral Irumporai defeated the Pandyas and the Cholas and brought immense wealth to his capital at a city called Vanchi. He is said to have distributed these treasures among the Pana poets.[11]

Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai

King Yanaikatchai Mantaran Cheral Irumporai preserved the territorial integrity of the Chera Kingdom under his rule. However, by the time of Mantaran Cheral the decline of the kingdom had begun. The Chera ruled from Kollimalai in the east to Tondi and Mantai on the western coast. He defeated his enemies in a battle at Vilamkil.[11]

The famous Pandya ruler Nedum Chezhian captured Mantaran Cheral as a prisoner. However, he managed to escape and regain the lost kingdom.[11]

Kanaikkal Irumporai

Kanaikkal Irumporai is said to have defeated a local chief called Muvan. The Chera then brutally pulled out the teeth of his prisoner and planted them on the gates of the city of Tondi. The later Kanaikkal Irumporai was captured by the Chola ruler Sengannan and he later committed suicide by starvation.[11]

Government and society during the Sangam era

Administration

Monarchy was the most important political institution of the Chera kingdom. There was a high degree of pomp and pageantry associated with the person of the king. The king wore a gold crown studded with precious stones. The king was an autocrat, but his powers were limited by a counsel of ministers and scholars. The king held daily durbar to hear the problems of the common men and to redress them on the spot.[30] The royal queen had a very important and privileged status and she took her seat by the side of the king in all religious ceremonies.[30]

Another important institution was the manram which functioned in each village of the Chera kingdom. Its meetings were usually held by the village elders under a banyan tree, and helped in the local settlement disputes. The manrams were the venues for the village festivals as well.[30] In the course of the imperial expansion of the Cheras the members of the royal family set up residence at several places of the kingdom. They followed the collateral system of succession according to which the eldest member of the family, wherever he lived, ascended the throne. Junior princes and heir-apparents (crown princes) helped the ruling king in the administration.[11]

The Cheras had a well-equipped army which consisted of infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots. There was also an efficient navy. The Chera soldiers made offering to the war goddess Kottavai before any military operation. It was traditional when the Chera rulers were victorious in a battle to wear anklets made out of the crowns of the defeated rulers.[30]

Foreign trade

Chera trade with foreign countries around the Mediterranean sea can be traced back to before the Common Era.[4][6] In the 1st century of the Common Era, the Romans conquered Egypt, which helped them to establish dominance in the Arabian sea trade. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea portrays the trade in the kingdom of Cerobothras in detail. Muziris was the most important port in the Malabar coast, which according to the Periplus, abounded with large ships of Romans, Arabs and Greeks. Bulk spices, ivory, timber, pearls and gems were exported from the Chera ports to Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Phoenicia and Arabia.[32] The Romans brought vast amounts of gold in exchange for pepper.[33][34][35]

Society and religion

Most of the Chera population followed native Dravidian practices. The worship of departed heroes was a common practice in the Chera kingdom along with tree worship and other kinds of ancestor worships. The war goddess Kottavai was propitiated with complex sacrifices. The Cheras probably worshiped this mother goddess. Kottavai was later assimilated into the present day form of the goddess Devi.[36] There is no evidence of snake worship in the Chera realms during the Sangam Age.[37]:17 Perhaps the Brahmins came to the Chera kingdom in the 3rd century BCE following the Jains and Buddhists. It was only in the 8th century CE that the Aryanisation of the Chera country reached its climax.[37]:10

A small percentage of the population followed Jainism, Buddhism and Brahmanism. These three philosophies came from northern India to the Chera kingdom.[37]:11 A small Jewish and Christian population also lived in the Chera territories.[38][39][39][40]

Decline of early Cheras

The 4th and 5th centuries witnessed the decline and fall of the Western Roman Empire. Also in the post-Sangam era, the Chera kingdom was invaded by a number of northern powers. A Kadamba record of the 5th century at the Edakkal cave in Wayanad bears testimony to the Kadamba presence in the deep south.[41] Chera kingdom seems to have been affected by the Kalabhra upheaval in the 5th and 6th centuries CE. According to Buddhist works, Kalabhra ruler Achuta Vikkanta kept the Chera, Chola and Pandya rulers in his confinement and established control over a large portion of southern India. The Kalabhras were defeated around the 6th century with the revival of Pallava and Pandya power.

The Chalukyas of Badami must have conducted temporary conquests of Malabar. An inscription of Pulakeshin I claims that he conquered the Chera ruler. A number of other inscriptions mentions their victories over the kings of Chera kingdom and Ezhil Malai rulers. Pulakeshin II (610–642) is also said to have conquered Chera, Pandya and Chola kingdoms. Soon the three rulers made an alliance and marched against the Chalukyas. But the Chalukyas defeated the confederation. Vinayaditya also subjugated the Chera king and made him pay tribute to the Chalukyas. King Vikramaditya is also said to have defeated the Cheras.

King Simhavishnu and Mahendra Varman are the first Pallava rulers to claim sovereignty over the Chera kingdom. Narasimha Varman and the Pandya ruler Sendan (654–670) also won victories over the Cheras. King Nandivarman II of the Pallavas allied with the Cheras in a fight against the Pandyas under Varaguna I. Rashtrakutas also claimed control over Cheras. Antidurga and Govinda III is said to have defeated the Cheras.

The Ay kingdom, south of the Chera kingdom, long functioned as an effective buffer state between a declining Chera kingdom and an emerging Pandya kingdom. Later the Pandyas conquered the Ays and a made it a tributary state. As late as 788 CE, the Pandyas under Maranjadayan or Jatilavarman Parantaka invaded the Ay kingdom and took the port city of Vizhinjam. However, the Ays did not seem to have submitted to the Pandyas, as they fought against them for almost a century.

Second/Later Cheras

Second/Later Cheras, formerly known as Kulasekharas were the nominal rulers of the Chera kingdom, a loose federation of regional chiefs, which existed between the 9th and 12th centuries CE.[42]

The rule of later Cheras was based at the city of Mahodayapuram near the present day Kodungalloor, Kerala.[43] The Perumal government was described by historian MGS Narayanan as a "Brahmin oligarchy with ritual sovereignty".[42]

The Chera kingdom of the Perumals was the only large state that existed in pre-modern Kerala. It was a loose federation of Aryan-Brahmin settlers ("Naduvazhis") nominally acknowledging the sovereignty of the Cheraman Perumal and supporting him in defensive wars against the other Tamil powers. There was a Brahmin oligarchy which supported the Perumal. Most of the Perumals were saintly scholars who remained influenced by the power of Brahmin councillors ( "Tali Adhikaris"). State formation was weak and state military enterprise in the imperial Chola style was out of the question.[44] In the Chera period the quasi-autonomous Brahmin settlements were administered by the "Sabha" under the supervision of the Naduvazhis. Naduvazhis were mostly the sons of Brahmins because of the Marumakkathayam system which promoted sambandham, a form of Brahmin-Sudra (Aryan-non-Aryan) matrimonial alliance.[44]

The Chera state had only a precarious existence for three centuries, within which the Perumals were subordinate to the neighboring Cholas for more than half a century. The Cholas often controlled the Chera state during the 11th century. The Cholas had conquered the Cheras but the latter continued to rule as feudatories of the Cholas for well over a hundred years. It was only in the last decades of the 11th century, when the power of the Chola kingdom had weakened, that the Perumal of Mahodayapuram asserted his sovereignty. But this did not last long. The reign of the last Perumal, Rama Varma Kulashekhara|Rama Kulasekhara, was disturbed by internecine quarrels which led to his abdication of throne in favour of his Son Kotha Varma[45] Subsequent to the disappearance of Rama Kulasekhara at the beginning of the 12th century, the land of Kerala was governed by dozens of Naduvazhis under a feudal system which went by the Brahminical codes of morality, precedents and traditions.[44]

The Chera state had extensive trade relations with countries of the outside world. Sulaiman and al-Mas'udi, the Arab travellers who visited Malabar Coast during the period, have testified to the high degree of economic prosperity achieved by the state from its foreign trade. Sulaiman makes specific mention of the brisk trade with China. Malayalam emerged as a distinct language during the Kollam era, and Hinduism became the prominent religion of the state.[45]

| Prof. Elamkulam Kunjan Pillai;[11] | Prof. M. G. S. Narayanan |

|---|---|

|

|

Cheras of Venadu

In the absence of a central power at Makkotai, the divisions of the Chera kingdom soon emerged as principalities under separate chieftains. The post-Chera period witnessed a gradual decadence of the Nambudiri-Brahmans and rise of the Nairs. The original Villavar Chera dynasty migrated to Kollam (Quilon) and merged with the Ay kingdom. Ramavarma Kulasekhara, the last Chera King of Makotaiya Puram (Kodungaloor), became the first ruler of the Chera-Ai Dynasty and was called Ramar Thiruvadi.[46]:137 The rulers of the kingdom of Venadu, based at port Quilon in southern Kerala, trace their relations to the Perumals of Makkotai. Venadu ruler Kotha Varma (1102–1125) probably conquered Kottar and portions of Nanjanadu from the Pandyas. Under the reign of Vira Ravi Varma the system of government became very efficient, and village assemblies functioned vigorously. Udaya Marthanda Varma's tenure was noted for the close relationship between the Venadu and Pandyas. By the time of Ravi Kerala Varma (1215–1240), Odanadu kingdom had acknowledged the authority of the Venadu rulers. The next Venadu ruler Padmanabha Marthanda Varma is alleged to have been killed by Vikrama Pandya in 1264 CE.[11]

The Pandyas probably led a successful military expedition to Venadu and captured the capital city of Quilon between 1250 to 1300 CE. The records of Jatavarman Sundara Pandya and Maravarman Kulasekhara Pandya testify the establishment of Pandya rule over Venadu Cheras.[11] The Chera-Ai Dynasty was a vassal country under the Pandyan dynasty. After the invasion of Malik Kafur in 1311 CE the Pandyan dynasty was defeated and the last Tamil Chera-Ai ruler Veera Udaya Marthanda Varma was forced to abdicate in favour of two Matriarchal princess from the Tulu Kolathiri kingdom called Attingal and Kunnumel Ranis.[46]:234

Ravi Varma Kulasekhara

The death of the celebrated Pandyan king Jayasimha initiated a civil war in Venadu. Ravi Varma Kulasekhara, the last of the Venadu kings, came to throne according to the patrilineal system, and came out successful in this battle. Ravi Varma ruled Venadu as a vassal of the Pandyas till the death of king Maravarman Kulasekhara. After the death of the king he became independent and even claimed the throne of the Pandyas (Ravi Varma had married the daughter of the deceased Pandya ruler). He later annexed large parts of southern India and raised Venadu Cheras to the position of a powerful military state for a short time. The chaotic situation in the Pandya kingdom helped his conquests. The Venadu ruler invaded Pandya kingdom and defeated the prince Vira Pandya. After annexing the entire Pandya state, he was crowned as "Emperor of South India" in 1312 at Madurai. He later annexed Tiruvati and Kanchi (the Chola kingdom). Under Ravi Varma Venadu attained a high degree of economic prosperity.[11]

The success of Ravi Varma was short lived and soon after his the death the region became a conglomeration of warring states. Venadu itself transformed into one these states. The line of Venadu kings after Ravi Varma continued through the law of matrilineal succession.

Aditya Varma Sarvanganatha (1376–1383) is known have defeated the Muslim raiders of the south and checked the tide of Islamic advance. Under the rule of Chera Udaya Marthanda Varma, the Venadu gradually extended their sway over the Tirunelveli region. Ravi Ravi Varma (1484–1512) was the ruler of Venad during the arrival of the Portuguese in India.[11]

Venadu after the Fall of Pandyans

The Tamil Chera-Ai dynasty of Venad continued to survive with their capital changed to Southern Tamil Nadu at Kalakkadu, Cheran Madevi and Kallidaikurichi. Boothala Veera Mathanda Varma (1516-1535) who had the titles Ventru Mankonda Boothala Veeran and Puli Marthandan, was the famous ruler of this dynasty. The Chera-Ai Dynasty was mixed with two other Tamil dynasties, the Pandyas and Cholas. The country which extended between Kollam to Cheranmadevi was called Desinga Nadu and the court language continued to be Tamil. After the war with the Vijayanagaram in 1535 this dynasty was weakened and survived until the 17th century.[46]:238 After the disappearance of Jayasimha Vamsham Kerala was dominated by matriarchal Tulu-Nepalese dynasties with roots from the Kolathiri dynasty of Kannur who then adopted the Tamil titles of Chera dynasty. The Kings from the matriarchal dynasties of Attingal and Kunnumel Ranis added their birthstars to their names unlike the Tamil rulers.

Copper-plate grants

The Vazhapalli Plates are a set of copper-plate grants issued by Kulasekhara Mahodayapuram King Rajashekhara Varman (820-844).[46]

The Tharisapalli plates are a set of copper-plate grants issued to Mar Sapir Iso, the leader of the Saint Thomas Christians by Ayyanadikal Thiruvadikal in 849, conferring on the Palli and Palliyar a large number of privileges, including the 72 royal rights. These copper-plates are still present at Devalokam Aramana Kottayam, the headquarters of Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (successor to the Saint Thomas Christians).[46][47][48]

The Jewish copper plate was given to the Cochin Jews by Kulasekhara (Later Chera dynasty) king Bhaskara Ravi Varman I (962-1019 CE). This inscription conferred on a Jewish leader Ousep Rabban the rights of the Anjuvannam and 72 other proprietary rights.

Mahodayapuram

Mahodaya Puram or Mahodaya Pattanam, Makotai was the capital city of Chera dynasty between 8th and 12th centuries CE. It was spread around present day Kodungallur (Cranganore), Thrissur district, and Kerala.[11]

The city was built around Tiruvanchikkulam temple (10°12′37″N 76°12′23″E / 10.2103°N 76.2064°ECoordinates: 10°12′37″N 76°12′23″E / 10.2103°N 76.2064°E) and was protected by high fortresses on all sides and had extensive pathways and palaces. The temple was a centre of Saivite cult in the early years of the later Chera age. The royal palace was at Gotramalleswaram, now known as Cheraman Parambu. The city administration was controlled by a special representative body, the Kuttam. Mahodaya Puram was also called Vanchi by the later Chera rulers after their former capital.[11]

The Chera rulers shifted their capital to Mahodayapuram from Vanchi. Chera ruler Kulashekhara Varman (9th century) styles himself in his works as the "Lord of Mahodayapuram". The famous Jewish Copper Plate grant (1000 CE) was issued by Muyirikkode (Mahodayapuram).[11]

Mahodayapuram was famous throughout South India in the 9th and 10th centuries as great centre of learning and science. A well-equipped observatory functioned there under the charge of Sankaranarayana (c. 840 – c. 900), the Chera court astronomer.[49] It functioned in accordance with the rules of astronomy laid down by Aryabhata. Chera ruler Sthanu Ravi equipped a section of the observatory with some special machines (the yantras; Rasi Chakra, Jalesa Sutra, Golayantra etc.) and hence it came to be called Ravi Varma Yantra Valayam. It seems that that arrangements had been made in the city for recording correct time and announcing it to the public from different centres by the tolling of bells at regular intervals of a Ghatika (25 minutes). IThis practice (Nazhikakkottu) continued until the early 15th century.[11]

The districts of the city were:[11]

- Senamugham

- Kottakkakam

- Gotramalleswaram

- Kodungallur

- Balakrideswaram, etc.

Decline and fall

In the 11th and 12th centuries, the Cholas attacked the Chera state from the west. The Chola ruler Raja Raja made a number of successful military campaigns to the Chera kingdom during the rule of Bhaskara Ravi. The Cholas attacked the capital from the north and ravaged the city. Chola records suggests the fall of the fort at Udagai (Makotai, Mahodayapuram) sometime before 1008 CE. Other records suggests the Chola ruler's long journey through forests for burning down Udagai.[11]

The Chola ruler Rajendra Chola probably surrounded the capital and killed the Chera king Bhaskara Ravi II in a decisive battle at Mahodayapuram in 1019 CE. The number of Chera generals and chieftains were also killed in the battle.[11]

During the long war during the rule of Rama Varma, Mahodayapuram and neighboring places were completely burnt down and destroyed by the Cholas.The prolonged wars had weakened the Chera power considerably and some chiefs ("Naduvazhis") took advantage of the chaotic opportunity and asserted their independence. The royal palace at Gotramalleswaram was probably also burnt down and the king is known to have stayed at multiple locations such as Nediatali in Kodungallur and at Kollam (1102 CE). Later the Rama Varma shifted his capital to Kollam.[11]

Keralolpathi mentions a Tulu invader from Alupa Dynasty, brother of Kavi Simharachan (Kavi Alupendra 1110-1160 CE) of Tulunadu, who assumed the title of Cheraman Perumal and established a dynasty at Valarpattinam near Kannur. He attacked Kerala with a large army derived from Ahichatra/Nepal.[50]

After the end of the Chera state, Mahodayapuram fell into the hands of the Kingdom of Perumpadappu. Traditionally, the rulers of Perumpadappu are regarded as descendants of the Chera rulers in the maternal line. In 1225 CE, the Perumpadappu ruler Vira Raghava issued the famous Syrian Christian Copper Plate grant to Iravi Kortanan from Mahodayapuram. Mahodayapuram served as the capital of Kingdom of Perumpadappu between the 13th and 15th centuries.[11]

See also

- History of Tamil Nadu

- History of Kerala

- Cheraman Perumal

- Mukundamala

- Kodungallur

- Economy of ancient Tamil country

- Industry in ancient Tamil country

- Sangam period

- Tamilakam

- Indo-Roman relations

- Indo-Roman trade relations

- Indian maritime history

References

- ↑ www.kerala.gov.in/docs/publication/2013/

- ↑ Bhanwar Lal Dwivedi (1994). Evolution of Education Thought in India. Northern Book Centre. p. 164. ISBN 978-81-7211-059-8. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- ↑ P L Kessler and Abhijit Rajadhyaksha (2010-04-29). "Kingdoms of South Asia - Indian Kingdom of the Cheras". Historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- 1 2 "Artefacts from the lost Port of Muziris." The Hindu. December 3, 2014.

- ↑ "Muziris, at last?" R. Krishnakumar, www.frontline.in Frontline, Apr. 10-23 2010.

- 1 2 "Pattanam richest Indo-Roman site on Indian Ocean rim." The Hindu. May 3, 2009.

- 1 2 "Ancient India: A History Textbook for Class XI (1999)" Ram Mohan Sharma; National Council of Educational Research and Training, India

- 1 2 "India – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ↑ (Ancient name, Chully ref: Akam. 149)

- ↑ Romila Thapar. Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press, 2004 pp 368

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 A Survey of Kerala History by A. Sreedhara Menon – Kerala (India) – 1967

- ↑ Sivaraja Pillai, The Chronology of the Early Tamils – Based on the Synchronistic Tables of Their Kings, Chieftains and Poets Appearing in the Tamil Sangam Literature.

- ↑ Vincent A. Smith (1 January 1999). The Early History of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-618-1. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ↑ Keay, John (2000) [2001]. India: A history. India: Grove Press. ISBN 0802137970.

- ↑ Robert Caldwell (1 December 1998). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Or South-Indian Family of Languages. Asian Educational Services. p. 92. ISBN 978-81-206-0117-8. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ M. Ramachandran, Irāman̲ Mativāṇan̲ (1991). The spring of the Indus civilisation. Prasanna Pathippagam, pp. 34. "Srilanka was known as "Cerantivu' (island of the Cera kings) in those days. The seal has two lines. The line above contains three signs in Indus script and the line below contains three alphabets in the ancient Tamil script known as Tamil ...

- ↑ Kamil Veith Zvelebil, Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, p.12

- ↑ K.A. Nilakanta Sastry, A History of South India, OUP (1955) p.105

- 1 2 Subodh Kapoor (1 July 2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia. Cosmo Publications. p. 1449. ISBN 978-81-7755-257-7. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ Barbara A. West (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 781. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ↑ V., Kanakasabhai (1997). The Tamils Eighteen Hundred Years Ago. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0150-5.

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamil (1973). The smile of Murugan: On Tamil literature of south India. Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 37–39. ISBN 90-04-03591-5.

The opinion that the Gajabahu Synchronism is an expression of genuine historical tradition is accepted by most scholars today

- ↑ Pillai, Vaiyapuri (1956). History of Tamil Language and Literature; Beginning to 1000 AD. Madras, India: New Century Book House. p. 22.

We may be reasonably certain that chronological conclusion reached above is historically sound

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil (1975). Tamil Literature. BRILL. p. 38. ISBN 978-90-04-04190-5. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ↑ "The Ramayana and Mahabharata: Book VII: In the Nilgiri Mountains". Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ V.Jayaram (9 January 2007). "The Ramayana Kishkindha". Hinduwebsite.com. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ "Britannica Article on Dravidian". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. 9 January 2004. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ "Mahabharata: The Great War and World History". Bvashram.org. Retrieved 2011-03-16.

- ↑ See report in Frontline, June/July 2003

- 1 2 3 4 5 A. Sreedhara Menon (1987). Political History of Modern Kerala. D C Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-81-264-2156-5. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ↑ See Mahavamsa – http://lakdiva.org/mahavamsa/. Since Senguttuvan (Kadal Pirakottiya Vel Kezhu Kuttuvan) was a contemporary of Gajabahu I of Sri Lanka he was perhaps the Chera king during the 2nd century CE.

- ↑ Hermann Kulke (28 October 2004). A History of India. Psychology Press. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ↑ http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/thscrip/print.pl?file=2007012800201800.htm&date=2007/01/28/&prd=th&

- ↑ "History of Ancient Kerala". Government of india. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Raoul McLaughlin, Rome and the distant East: trade routes to the ancient lands of Arabia, India and China Continuum International Publishing Group, 6 July 2010

- ↑ P. 104 Indian Anthropologist: Journal of the Indian Anthropological Association By Indian Anthropological Association

- 1 2 3 Cultural heritage of Kerala: An Introduction. A. Sreedhara Menon. East-West Publications. 1978.

- ↑ The Jews of India: A Story of Three Communities by Orpa Slapak. The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. 2003. p. 27. ISBN 965-278-179-7.

- 1 2 The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 5 by Erwin Fahlbusch. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing - 2008. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-8028-2417-2.

- ↑ Manimekalai, by Merchant Prince Shattan, Gatha 27

- ↑ The official web portal of Government of Kerala. "History". Kerala.gov.in. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- 1 2 M. G. S. Narayanan, Perumals of Kerala: Political and Social Conditions of Kerala Under the Cēra Perumals of Makotai (c. 800 CE-1124 CE). Xavier Press, 1996

- ↑ Focus on a PhD thesis that threw new light on Perumals R. Madhavan Nair [The Hindu]

- 1 2 3 MGS Narayanan. Gods and Ancestors in Development: A study of Kerala Rethinking Development: Kerala's Development Experience, Volume 1. Concept Publishing Company, 01-Jan-1999

- 1 2 A Sreedhara Menon. A Survey Of Kerala History D C Books, 01-Jan-2007 - Kerala (India)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Keralacharitram ("The history of Kerala"), A. Sreedhara Menon, D. C. Books 2008, Kottayam, Kerala, India.

- ↑ M. G. S. Narayanan (1972), Cultural Symbiosis, Kerala Society.

- ↑ George Menachery (1998) Indian Church History Classics, Vol. I, The Nazranies, SARAS.

- ↑ George Gheverghese Joseph (2009). A Passage to Infinity. New Delhi: SAGE Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 13. ISBN 978-81-321-0168-0.

- ↑ കേരളോല്പത്തി(“Keralolpathi”), Velayadhan Panikkassery, CURRENT BOOKS DC Press (P) Ltd, Kottayam-12 2008. P.37

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chera Dynasty. |

- Mahavidwan R.Raghava Iyengar, Vanjimanagar (1918, 1932) University of Madras

- Inscriptions of India – Complete listing of historical inscriptions from Indian temples and monuments

- Tamil Coins, R. Nagasamy

- A magnum opus on Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions – Book review

- Mahavamsa

- Aihole Inscription of Pulakeshin II

- Ashoka's Rock Edicts

External links

| ||||||