Chengdu J-7

| J-7 / F-7 Airguard | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| An upgraded version of F-7 of Pakistan Airforce known as F-7PG. | |

| Role | Fighter aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Chengdu Aircraft Corporation/Guizhou Aircraft Industry Corporation |

| First flight | January 1966 |

| Status | Operational |

| Primary users | People's Liberation Army Air Force Pakistan Air Force Bangladesh Air Force Korean People's Air Force |

| Produced | 1965–2013 |

| Number built | 2,400+ |

| Developed from | Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 |

| Variants | Guizhou JL-9 |

The Chengdu J-7 (Chinese: 歼-7; third generation export version F-7; NATO Code: Fishbed) is a People's Republic of China license-built version[1] of the Soviet Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21. Though production ceased in 2013, it continues to serve, mostly as an interceptor, in several air forces, including the People's Liberation Army Air Force. The J-7 was extensively re-developed into the CAC/PAC JF-17 Thunder, which became a successor to the type.[2][3]

Design and development

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union shared most of its conventional weapons technology with the People's Republic of China. The famous MiG-21, powered by a single engine and designed on a simple airframe, were inexpensive but fast, suiting the strategy of forming large groups of 'people's fighters' to overcome the technological advantages of Western aircraft. However, the Sino-Soviet split abruptly ended the initial cooperation, and from July 28 to September 1, 1960, the Soviet Union withdrew its advisers from China, resulting in the project being stopped in China.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev unexpectedly wrote to Mao Zedong in February, 1962, to inform Mao that the Soviet Union was willing to transfer MiG-21 technology to China, and he asked the Chinese to send their representatives to the Soviet Union as soon as possible to discuss the details. The Chinese viewed this offer as a Soviet gesture to make peace, and they were understandably suspicious, but they were nonetheless eager to take up the Soviet offer for an aircraft deal. A delegation headed by General Liu Yalou, the commander-in-chief of the People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) and himself a Soviet military academy graduate, was dispatched to Moscow immediately, and the Chinese delegation was given three days to visit the production facility of the MiG-21, which was previously off-limits to foreigners. The authorization for this visit was personally given by Nikita Khrushchev, and on March 30, 1962, the technology transfer deal was signed. However, given the political situation and the relationship between the two countries, the Chinese were not optimistic about gaining the technology, and thus they were prepared for reverse engineering.

Russian sources state that several complete examples of the MiG-21 were sent to China, flown by Soviet pilots, and China also received MiG-21Fs in kits, along with parts and technical documents. Just as the Chinese had expected, however, when the Soviets delivered the kits, parts and documents to Shenyang Aircraft Factory five months after the deal was signed, the Chinese discovered that the technical documents provided by the Soviets were incomplete and that some of the parts could not be used. China set about to reverse-engineer the aircraft for local production, and in doing so, they succeeded in solving 249 major problems and reproducing eight major technical documents that were not provided by the Soviet Union. The Discovery Channel's Wings Over The Red Star series claims that the Chinese intercepted several Soviet MiG-21s en route to North Vietnam (during the Vietnam War), but these aircraft did not perform in a manner consistent with their original specifications, suggesting that the Chinese actually intercepted down-rated aircraft that were intended for export, rather than fully capable production aircraft. For this reason, the Chinese had to re-engineer the intercepted MiG-21 airframes in order to achieve their original capabilities. This re-engineering effort was largely successful, as the Chinese-built J-7 aircraft showed only minor differences in design and performance from the original Soviet MiG-21.

In March 1964, Shenyang Aircraft Factory began the first domestic production of the J-7 jet fighter, which they successfully accomplished the next year. However, the mass production of the J-7 aircraft was severely hindered by an unexpected social and economic problem—the Cultural Revolution—that resulted in poor initial quality and slow progress, which, in turn, resulted in full-scale production only coming about in the 1980s, by which time the original aircraft design was showing its age. The J-7 only reached its Soviet-designed capabilities in the mid 1980s. However, the fighter is affordable and has been widely exported as the F-7, often with Western systems incorporated, like the ones sold to Pakistan. China later developed the Shenyang J-8 based both on the expertise gained by the program, and by utilizing the incomplete technical information acquired from the Soviet Ye-152 developmental jet.

In May 2013, J-7 production has ceased after decades of manufacturing. The last 12 F-7BGIs were delivered to the Bangladeshi Air Force.[4]

Operational history

Most actions carried out by the F-7 export model have been air-to-ground missions. In air-to-air missions, there have rarely been any encounters resulting in dogfights.

Africa

- Namibia

Namibian AF ordered 12 Chengdu F-7NMs in August 2005. Chinese sources reported the delivery in November 2006. This is believed to be a variation of the F-7PG acquired by Pakistan with Grifo MG radar.[5]

- Nigeria

In early 2008, Nigeria procured 12 F-7NI fighters and three FT-7NI trainers to replace the existing stock of MiG-21 aircraft. The first batch of F-7s arrived in December 2009.[6]

- Sudan

Sudanese F-7Bs were used in the Second Sudanese Civil War against ground targets.

- Tanzania

Tanzanian Air Force F-7As served in the Uganda–Tanzania War against Uganda and Libya in 1979. Its appearance effectively brought a halt to bombing raids by Libyan Tupolev Tu-22s.

- Zimbabwe

During Zimbabwe's involvement in the DRC, six or seven F-7s were deployed to the Lubumbashi IAP and then to a similar installation near Mbuji-Mayi. From there, AFZ F-7s flew dozens of combat air patrols in the following months, attempting in vain to intercept transport aircraft used to bring supplies and troops from Rwanda and Burundi to the Congo. In late October 1998, F-7s of the No.5 Squadron were used in an offensive in east-central Congo. This began with a series of air strikes that first targeted airfields in Gbadolite, Dongo and Gmena, and then rebel and Rwandan communications and depots in the Kisangani area on November 21.[7]

Europe

- Albania

The stationing of F-7As in north of the country, near the border successfully checked Yugoslav incursions into Albanian airspace.[8]

East and South-East Asia

- China

In the mid 1990s, the PLAAF began replacing its J-7Bs with the substantially redesigned J-7E variant. The wings of the J-7E have been changed to a unique "double delta" design offering improved aerodynamics and increased fuel capacity, and the J-7E also features a more powerful engine and improved avionics. The newest version of the J-7, the J-7G, entered service with the PLAAF in 2003.

The role of the J-7 in the People's Liberation Army is to provide local air defence and tactical air superiority. Large numbers are to be employed to deter enemy air operations.

- Myanmar

F-7Ms were planned to use for interception. However, they are now out of service and stored as reserve aircraft as new superior fighters arrived.

Middle East

- Egypt

Relations between Egypt and Libya deteriorated after Egypt signed a peace accord with Israel. Egyptian Air Force MiG-21s shot down Libyan MiG-23s, and F-7Bs were deployed to the Egyptian-Libyan border along with MiG-21s to fend off possible further Libyan MiG-23 incursions into Egyptian airspace.

- Iran

Although not in any known combat actions, it was in several movies portraying Iraqi MiG-21s during the Iran–Iraq War. One tells the story of an Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force strike on the Iraqi nuclear reactor at Osirak on September 30, 1980. Another "Attack on H3" tells the story of the 810 km-deep raids into the Iraqi heartland against Iraqi Air Force airfields on April 4, 1981, and other movies depicting the air combat in 1981 that resulted in the downing of around 70 Iraqi aircraft. However, unconfirmed reports claimed that during the later stages of the war, these aircraft were used for air-to-ground attacks. On July 24, 2007 an Iranian F-7 crashed in northern eastern Iran. The plane crashed due to technical difficulties.[9]

- Iraq

F-7Bs paid for by Egypt arrived too late for the aerial combat in the early part of the Iran–Iraq War, but later participated mainly in air-to-ground sorties.

South Asia

- Bangladesh

The Bangladeshi Air Force, currently operates F-7MB Airguards, and F-7BG/Gs interceptors. The F-7MB/A-5Cs will be replaced by 16 F-7BGI fighters by 2014. BAF has also upgraded all of its F-7BGs to fire Chinese built LS-6 and LT-2 ground attack munitions, giving them a potent strike capability.

- Pakistan

Pakistan is currently the largest non-Chinese F-7 operator, with ~120 F-7P and ~60 F-7PG. The Pakistan Air Force is to replace its entire fleet of F-7 with the JF-17 multirole fighter, all F-7P are planned to be retired and replaced with JF-17 Thunder aircraft by 2015.

- Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Air Force used three F-7BS and for ground attack missions against the LTTE and three FT-7 trainer. Due to the lack of endurance and payload, SLAF some times uses their F-7s for pilot training purposes.[10]

Early 2008 the air force received six more advanced F-7Gs, these will be primarily used as interceptors. All The F-7G's, F-7BS's and FT-7s are flown by the No 5 Jet Squadron.[11]

Sri Lankan officials reported that on 9 September 2008, three Sri Lankan Air Force F-7s were scrambled after two rebel flown Zlín-143 were detected by ground radar, two were sent to bomb two rebel airstrips at Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi areas, the government claims the third intercepting one ZLin-143 resulting in one LTTE Zlín-143 shot down by the chasing F-7G using air-to-air missiles while the rebel flown light aircraft was returning to its base at Mullaitivu after a bombing run against Vavuniya base.[12][13]

Variants

Approximately 48 variants of the J-7 exist and are listed below.

Chinese variants

- J-7

- (a.k.a. Type 62) The first reverse-engineered copies of the MiG-21F-13 "Fishbed-C" by Shenyang Aircraft Factory in 1966, powered by WP-7 (a R-11F-300 copy). Only 12 were produced.[14][15]

- J-7I

- An improved J-7 variant built by Chengdu Aircraft Industry Corp (CAC) in the 1970s, it differs from the J-7 in that the fixed intake of the J-7 was replaced by a variable intake, the armament reverted to 2x 30mm cannons, a brake parachute container was added to the base of the fin under the rudder, whilst the WP-7 engine was retained. Production and service with the PLAAF and PLANAF was very limited due to design flaws, quality control issues and poor performance. In 1960s, as soon as PLAAF received PL-2 air-to-air missile, J-7Is started to attempt using PL-2 missiles to intercept USAF reconnaissance UAVs. Due to PL-2s' fuse is designed to target larger aircraft, these attempts were unsuccessful to some degree. Later J-7Is successfully shot down unknown numbers of USAF UAVs with air-to-air rockets.[16]

- J-7I (modified)

- One of the biggest flaws of the original J-7 was in its hydraulic system, which suffered leaks. As many as 70% of the J-7s in some PLAAF Squadrons were grounded due to this issue. An extensive redesign was implemented to solve this problem. The resulting J-7I (modified) had much better hydraulic systems, and although the system still did not reach the Western standard of the same era, the quality was greatly improved in comparison to the earlier system it had replaced, and was considered acceptable by J-7 users.

- J-7II

- Improved J-7I variant built in the 1970s and limited all-weather fighter with two 30mm guns and a WP-7B engine. The forward-hinged canopy jettisoned with the ejection seat of the Soviet design proved to be unsuccessful and was replaced by a rearward hinged canopy jettisoned before the ejection seat.

- J-7IIA

- Improved J-7II variant in early 1980s with Western avionics, such as the British Type 956 HUD, which became standard for J-7 fighters from then on.

- J-7IIM

- Conversion package to upgrade domestic Chinese J-7s to F-7M:standard.

- J-7IIH

- Improved J-7II variant with enhanced ground attack capability. First J-7 model to have a multi-function display, which is located to the upper right corner of the dashboard.[17] J-7IIH is the first J-7 fighter that is capable of using PL-8 air-to-air missile.[18]

- J-7IIK

- Conversion package resulted from experienced gained from J-7MP:to upgrade domestic Chinese J-7 to J-7MP/F-7MP/F-7P standard.

- J-7III

- Reverse-engineered copies of MiG-21MF "Fishbed-J," reportedly obtained from Egypt[19] by Chengdu Aircraft Industry Corp. (CAC) with JL-7 fire-control radar (weight was 100 kg, maximum range is 28 km, and MTBF is 70 hours). Liyang WP-13 turbojet engine, new HUD/avionics, and improved fuel capacity. The new avionics included Type 481 data link, which enables the ground-controlled interception centers to feed directions directly to the autopilots of J-7IIIs to fly "hands off" to the interception, and Type 481 data link was latter included as standard equipment of all later models. Limited production of 20-30.

- J-7B

- The most obvious visual difference between this model and earlier models is that the smaller canopy and the small window behind it on earlier models were replaced by a larger canopy on this model, so that the small window no longer existed.

- J-7BS

- First J-7 to have 4 under-wing pylons.

- J-7E

- Improved variant of the J-7II, developed in 1987 as a replacement for the J-7II/F-7B. A new double-delta wing, WP-13F turbojet engine, British GEC-Marconi Super Skyranger radar, increased internal fuel capacity, and improved performance. It is 45% more maneuverable than the J/F-7M, while the take-off and landing distance is reduced to 600 meters, in comparison to the 1,000 meter take-off distance and 900 meter landing distance of earlier versions of the J-7.[20] J-7E is the first of the J-7 family to incorporate HOTAS, which has since become standard on the later versions. This version is also the first of J-7 series to be later upgraded with helmet mounted sights (HMS), however, it is reported that the helmet mounted sight is not compatible with radars, and air-to-air missiles must be independently controlled by either HMS or radar, but not both.

- J-7EB

- A unarmed J-7EB variant was used by the People's Liberation Army Air Force August 1 Aerobatic Team.

- J-7EH

- J-7E derivative used by People's Liberation Army Naval Air Force with capability to carry anti-ship missiles such as C-802. However, the due to the limitation of its airborne radar, J-7EH cannot independently engage shipping targets and after the launching of the anti-ship missiles, the targeting information must be provided by other aircraft such as the Y-8X and Harbin SH-5.

- J-7FS

- Technology demonstration aircraft built by CAC, with redesigned under-chin inlet and WP-13IIS engine. First flew in 1998, only two prototypes were built before being replaced by J-7MF[21]

- J-7G

- The ultimate J-7, improved from the double delta wing J-7E by CAC, first flew in 2002. Equipped with a new KLJ-6E PD radar, which is reported to be SY-80 radar with SY is short for Shen Ying, meaning Celestial Eagle in Chinese. This radar a Chinese development of the Italian Pointer-2500 ranging radar used for the Q-5M, and the Italian radar itself was a development of Pointer radar, the Italian copy of Israeli Elta EL/M-2001. In comparison to the Italian Grifo series radar on Pakistani F-7s, the SY-80 weighs more at 60 kg, and the range is also shorter, at 30 km. However, the radar does have a feat that the Italian radars do not have: it is fully compatible with helmet-mounted sights (HMS) so that both the radar and HMS can be worked together to control PL-8/9 air-to-air missiles. One 30 mm gun was removed, and a more powerful engine installed.[20] It is said that in a close quarter combat, it has a maneuverability as good as the early variant of F-16.

- J-7GB

- Unarmed version of the J-7G used to replace the J-7EB for the August 1st Aerobatic team.

- J-7M

- Until the 2000s (decade), there was at least a F-7M used by Chinese as a radar and avionics test bed. Differs from other models in that there was no fixed radars and avionics due to the different equipment being tested.

- J-7MF

- Successor of the J-7FS, with rectangular under-chin inlet similar to that of the Eurofighter Typhoon, and movable canards for better aerodynamic performance. No prototypes were ever built before the project being abandoned in favor of the FC-1.

- J-7MG

- J-7E armed with GEC-Marconi Super Skyranger radar with planar slotted array and Martin-Baker ejection seat for potential customers' evaluation. Pakistan and Bangladesh evaluated the aircraft, and evolved to F-7MG.

- J-7MP

- After nearly two years use of the F-7M, Pakistani Air Force (PAF) returned the 20 F-7M aircraft to China in the late 1980s with recommendations for 24 upgrades, including replacing the original GEC-Marconi Type 226 Skyranger radar with the Italian FIAR Grifo-7 radar, and AIM-9 Sidewinder capability.

- The Italian radar weighs 55 kg, had a slot antenna planar array, and had a range greater than 50 km, while the British radar only weighs 42 kg, with a parabolic antenna, but only had range of 15 km. Both radars have a mean time between failure rate of 200 hours. J-7MP:is the design specially tailored to Pakistani requirements.

- J-7PG

- Alternative to J-7MG, similar to the J-7MG except with Italian FIAR Grifo-MG radar, which further increased the sector of scan to +/- 30 degrees from the +/- 20 degrees of Grifo-Mk-II on F-7P. The Grifo-MG radar has better ECCM, look-down and shoot-down capabilities than its predecessor Grifo-Mk-II, while the weight remained the same. The number of targets can be tracked simultaneously is increased from the original 4 of the Grifo-Mk-II to a total of 8 of the Grifo-MG. Pakistan and Bangladesh evaluated the aircraft, and evolved to F-7PG.

- JJ-7

- Dual-seat J-7 trainer and Chinese equivalent of the MiG-21U Mongol-A design. Originally built by Guizhou Aircraft Design Institute and Guizhou Aircraft Company (now Guizhou Aviation Industry Group/GAIC) in 1981.[22][23]

- JJ-7I

- Chinese equivalent of the Soviet MiG-21US trainer with domestic Type-II ejection seat. Only a very small number were built before converting to the JJ-7II.

- JJ-7II

- JJ-7I with Rockwell Collins avionics that became standard for later J-7 models.

- Also known as FTC-2000 Mountain Eagle (Shan Ying), new two-seat trainer derived from the JJ-7 series. Built by GAIC in 2000s (decade) as the low-cost solution to JJ-7 trainer replacement.[24]

- JZ-7

- Reconnaissance version of the J-7, Chinese equivalent of MiG-21R. In addition to the photo reconnaissance, this aircraft was the first to have the domestically developed ESM reconnaissance pod.

- J-7 Drone

- Unmanned J-7 remote-controlled drones mostly converted from J-7I fighters.

Export variants

- F-7IIA - Export version of the J-7IIA, with the pitot re-located to the intake upper lip on the starboard side, a WP-7BM engine, stronger windscreen, improved zero-zero ejection seat and GEC-Marconi Type956 HUD/ Weapons Aiming Computer, as well as re-inforced landing gear.

- F-7IIN 22 modified F-7M sold to Zimbabwe, with the domestic Chinese avionics replacing the Western avionics, originally believed to be fitted with JL-7A radar. There were reports in 2005 that radars on the fighters had been upgraded.

- F-7III Export version of the J-7III with different missile launching rails that are compatible with French R550 Magic Air-to-air missiles. No sales have been reported.

- J-7IIIA. Improved J-7III/F-7-3 with JL-7A radar and WP-13FI turbojet engine, jointly developed by CAC and Guizhou Aviation Industry Group (GAIG). Limited production of 20-30. Straight topped spine like that of MiG-21PF and PFMA.[19]

- F-7A Limited export version of the J-7sans suffixe with a WP-7B engine, one 30mm gun, and 2 under-wing pylons. It was exported to Albania and Tanzania. In accordance with Mao Zedong's foreign aid policy at the time, the export version was armed with better equipment than the domestic one.[22]

- F-7B Export version of the J-7II with re-wired pylons using the French R550 Magic Air-to-air missiles. Sold to Egypt (a total of 150 F-7Bs and F-7Ms), Iraq, and Sudan from 1982-1983. The Iraqi units were paid by Egypt.

- F-7BG 16 were delivered to Bangladesh in 2006 including 4 two-seater FT-7BG. The capability to carry reconnaissance pods and operate the equipment inside the pods from the cockpit of earlier F-7MB is retained. Reported to use Grifo MG radar.[5]

- F-7BGI Upgraded version for Bangladesh Air Force ordered in 2011. Based on J-7G, guided munition capable.

- F-7 BGI has a speed of Mach 2.2

- 7 Hard-points to carry air-to-air missiles, laser-guided bomb, GPS-guided bombs, drop tanks

- Full glass cockpit.

- can carry 3000 kg bomb, including Chinese laser-guided bombs.

- F-7 BGI has KLJ-6F radar Fire control Radar with 86 km+ Range which is near BVR or BVR considering what is the silver lining between them and can track 6 and engage 2 enemy aircraft simultaneously.

- F-7 BGI can carry C-704 Antiship Missiles (Therefore, maritime also possible)

- afterburner: F-7 BGI (82 kN) thrust

- Missiles procurement are currently unknown for F-7 BGI but they can fire the 70–75 km range PL-12,PL-11 and also PL-2, PL-5, PL-7, PL-8, PL-9, Magic R.550 and AIM-9 .

- F-7 BGI got J-7G2 Airframe with double delta wing. This improves the lift at high angles of attack and delays or prevents stalling.

- G-limit: +8 g / -3 g

- Service ceiling: 17,500 m (57,420 ft) for F-7 BGI

- 3 Multi functional HUD displays and Hotas.

- Chinese Helmet Mounted Sights.

- Reportedly more maneuverable than most of the Mig21s and many of the other contemporary fighters.

- F-7BS export versions of the J-7BS, hybrid of F-7B and F-7M, 4 units were sold to Sri Lanka in 1991. These units lacked HUDs.

- F-7D Export version of the J-7IIIA with different missile l7aunching rails that are compatible with the French R550 Magic Air-to-air missiles. No sales have been reported.

- F-7M Airguard Improved J-7II variant for export with Western avionics, with British GEC-Marconi as the prime contractor. Program initiated in 1978 and took six years to complete, after 10 rounds of negotiation. Western avionics includes:

- British Type 226 Skyranger radar: Ranging radar that weighs 41 kg with a range of 15 km.

- British Type 956 HUDAWAC: This HUD has a built-in weapon aiming computer, hence the name Head-Up Display And Weapon Aiming Computer.

- British Type 50-048-02 digitized air data computer

- British Type 2032 camera gun, which is linked to HUD with capability to interchange rolls of film while airborne. Each roll of film lasts more than 2 minutes

- American converter that is over 30% more efficient in comparison to the original Chinese converter.

- American Type 0101-HRA/2 radar altimeter with range increased to 1.5 km in comparison to the original 0.6 km of the Chinese radar altimeter it had replaced.

- British AD-3400 secured radio with range in excess of 400 km at 1.2 km altitude.

- Other improvement includes domestic newly designed CW-1002 air data sensor developed in conjunction with the Western avionics, and WP-7B/WP-7BM engine.

- A totally different wing enabled the take-off and landing distance to be reduced by 20%, while increasing the aerodynamic performance in dogfights. According to customers' claims, F-7M is nearly 40% more effective than MiG-21 in terms of overall performance. It can use French R550 Magic and PL-7 Air-to-air missiles. It was sold to Myanmar, Egypt and Bangladesh in 1980s.

- Pakistan contribution: Although Pakistan did not purchase any F-7M and later returned all 20 F-7M's to China after evaluation to require China to provide a better fighter (which eventually resulted in F-7MP/P), Pakistan did provide important support for F-7M program, including:

- In the last quarter of 1982, test flights revealed that the radar was plagued by the problem of picking up ground clutter. China did not have any Western radar assisted air-to-ground attack experience, and had no idea of conducting the necessary flight tests specifically designed for the Western avionics to solve the problem. Pakistani Air Force provided pilots (including F-16 pilots) to China to perform these tests and helped in solving this problem.

- Chinese 630th Institute responsible for F-7M program lacked the facility and experience to conduct live round weapon tests with advanced Western avionics, and it also lacked the capability to conduct mocked air combat with Western aircraft. Therefore, from June, 1984 to September, 1984, two F-7Ms were sent to Pakistan to conduct such tests. Pakistan Air Force once again provided F-16 pilots to help to complete the tests, with the Chinese team in Pakistan led by Mr. Chen Baoqi (陈宝琦) of the Chinese Aviation Ministry and Mr Xie Anqing (谢安卿) of Chengdu Aircraft Co.

- F-7MB 16 F-7MB units exported to Bangladesh, with the capability to carry reconnaissance pods and operate the equipment inside the pods from the cockpit.

- F-7MF Italian-proposed export version of the J-7MF armed with a proposed FIAR Grifo-M radar. The plan was abandoned in favor of the FC-1/JF-17, but the aircraft was reportedly used to test the FIAR Grifo-S radar for FC-1/JF-17. However, it is rumored that of the a total 80 F-7PG ordered by Pakistan, the last 30 were switched to the F-7MF, but this cannot be confirmed.

- F-7MG Export variant of the J-7MG, with the single piece windshield replacing the 3-piece windshield of the J-7MG. Evolved to F-7BG. Zimbabwe bought at least 12 of these in 2004.[25]

- F-7MP A J-7MP converted from the F-7M. 20 were delivered and are in Pakistani service. It is also known as the F-7P Skybolt like the F-7P. The Pakistani Air Force does not distinguish the two since the only difference was how they were produced. From this model onward, all F-7 fighters delivered to Pakistan are equipped with a Chinese helmet mounted sight (HMS), which greatly enhanced the capability in dogfights.[26]

- F-7N 18 export F-7MP version to Iran with domestic Chinese avionics replacing the Western avionics. Reportedly, the radar was SY-80 pulse doppler radar.

- F-7P Newly built Skybolt for the Pakistani Air Force (PAF). A total of 60 were built. Starting with this model, F-7s in the Pakistani service began to be upgraded with the Italian FIAR Grifo-Mk-II radar license assembled by the ISO - 9002 certified Kamra avionics, Electronics and Radar Factory of the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC).

- In comparison to the Grifo-7, the new radar only weighs an extra 1 kg (56 kg total), but the sector of scan was increased to ±20 degrees from the original ±10 degrees of Grifo-7. The newer radar also had improved ECM and look-down and shoot-down capability, and can track 4 targets simultaneously while engage one of four target tracked.

- F-7PG Export variant of the J-7PG, with the single piece windshield replacing the 3-piece windshield of the J-7PG. Pakistan ordered a total of 80 in two batches, with 50 and 30 respectively in each. According to the Pakistan Air Force, the performance at high altitude of the F-7PG has increased more than 83% in comparison to the F-7P/MP. Just like the earlier Italian FIAR Grifo-Mk-II radar on F-7MP/P, the Italian FIAR Grifo-MG radar of F-7PG will be assembled under license by the ISO - 9002 certified Kamra avionics, Electronics and Radar Factory of the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC).

- F-7W First J-7 export model with a HUD. The smaller canopy and the small window behind it were replaced by a larger canopy so that the small window no longer existed on J-7 models from then on. The first customer was Jordan, but the aircraft did not enter Jordanian service, instead, the aircraft ended up in Iraqi hands.

- FT-7 Export version of the JJ-7. It used the domestic Chinese Type-II ejection seat, replacing the Chinese copy of the original Soviet design, because the Soviet design was less reliable.

- FT-7A Conversion package offered to Soviet MiG-21U trainer customers such as Egypt to replace the original Soviet-built ejection seats with Chinese built Type-II ejection seat, and a rear hinged canopy that would be jettisoned before the ejection seat instead of the forward hinged canopy jettisoned with the ejection seat.

- FT-7B Export version of JJ-7II, the first J-7 model to have a Martin-Baker ejection seat.

- FT-7M Trainer version of the F-7M. This is the J-7 trainer version on which the head-up display became standard.

- FT-7P Trainer version of the F-7MP and F-7P. Unlike most Chinese built J-7 trainers which lack radars, the FT-7P was armed with the same radar on the single seat version and thus fully capable for combat.

- FT-7PG FT-7 trainer variant of the F-7PG for the Pakistani Air Force. The rear seat is 0.5 metre higher than the front seat, so the periscope is eliminated.

- Super-7 did away with British upgrades to the F-7M in the mid-1980s. After a successful deal with Chinese in the early 1980s resulting in the F-7M, the United Kingdom offered a further upgrade to improve the performance of the F-7M by adopting either General Electric F404 or Pratt & Whitney PW 1120 turbofan engines. The radar options would include the Red Fox, a repackaged version of the Blue Fox radar used on Sea Harrier FRS Mk 1, or the Emerson AN/APG-69. Although radar tests were successful, the upgrade was rejected before any engine tests, because a single radar or a single engine had cost more than a new J-7 (2 million United States Dollars, 1984 price).

- F-7S Saber II Replacement for the Super-7. Re-designed F-7M by Grumman Corporation for the Pakistan Air Force. Side intakes replaced the nose intake and a General Electric AN/APG-67 radar on F-20 Tigershark would have been adopted. The program was terminated due to the Tiananmen Square protest of 1989.

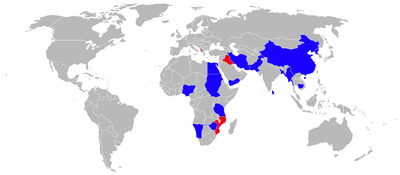

Operators

Current

- Bangladesh Air Force: 32 x F-7 in service. 10× F-7MB reportedly retired, 16 F-7BG received in 2006 and 16 F-7BGI received in 2013.

- People's Liberation Army Air Force: 290× J-7 plus 40× JJ-7 trainers remained in service (As of February 2012).[27]

- People's Liberation Army Naval Air Force: 30× J-7D/E remained in service (As of February 2012).[27]

- Egyptian Air Force: 74 F-7 in service,[28]

- Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force: 21 F-7 in service.[29]

- Myanmar Air Force: 24× F-7M and 6× FT-7 trainers remained in service (As of February 2012).[27]

- Namibian Air Force: Six F-7 and two FT-7 in service, 8 F-7NG on order.[30]

- Nigerian Air Force: 12 F-7 and 2 FT-7.[31]

- North Korean Air Force: As of February 2012, 180× F-7 remained in service. However, reports of dire levels of serviceability suggest an airworthiness rate of less than 50%.[27]

- Pakistan Air Force: As of February 2012, 143× F-7P/PG plus 7× FT-7 remained in service.[27]

- No. 19 Squadron Sherdils – Operated F-7P/FT-7P from 1990 [32] until April 2014.[33] Replaced by F-16A/B Block 15 ADF.[34]

- CCS Dashings - Operated F-7P from 1992 until January 2015. Replaced by JF-17 Block 1.[35]

- Sri Lankan Air Force: 9× F-7/GS/BS and 1× FT-7 trainer remained in service (As of February 2012).[27]

- Sudanese Air Force: 20× F-7 in service.[36]

- Tanzanian Air Force: Originally having had 11 × F-7 in service,[37] Tanzania replaced them with 12 new J-7's (single-seat) under the designation J-7G and 2 dual-seat aircraft designated F-7TN in 2011. Originally ordered in 2009, the deliveries were completed and the aircraft are now fully operational at the air bases in Dar es Salaam and Mwanza. The new aircraft are equipped with a KLJ-6E Falcon radar, thought to be developed from the Selex Galileo Grifo 7 radar. The J-7G's primary weapon is the Chinese PL-7A short-range infrared air-to-air missile.[38]

- Air Force of Zimbabwe: 7× F-7 in service[39]

Former

- Albanian Air Force: Total 12 F-7A in service from 1969 through 2004,now retired.[40][41][42]

- Iraqi Air Force: 80× F-7, all retired.

- United States Air Force [43] (Foreign Technology Evaluation: MiG-21F-13)

Specifications (J-7MG)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004[44]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 14.885 m (Overall) (48 ft 10 in)

- Wingspan: 8.32 m (27 ft 3½ in)

- Height: 4.11 m (13 ft 5½ in)

- Wing area: 24.88 m² (267.8 ft²)

- Aspect ratio: 2.8:1

- Empty weight: 5,292 kg (11,667 lb)

- Loaded weight: 7,540 kg (16,620 lb) (two PL-2 or PL-7 air-to-air missiles)

- Max. takeoff weight: 9,100 kg (20,062 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Liyang Wopen-13F afterburning turbojet

- Dry thrust: 44.1 kN (9,921 lbf)

- Thrust with afterburner: 64.7 kN (14,550 lbf)

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 2.0 (2,200 km/h (1,189 knots, 1,375 mph)) IAS

- Stall speed: 210 km/h (114 knots, 131 mph) IAS

- Combat radius: 850 km (459 nmi, 528 mi) (air superiority, two AAMs and three drop tanks)

- Ferry range: 2,200 km (1,187 nmi, 1,367 mi)

- Service ceiling: 17,500 m (57,420 ft)

- Rate of climb: 195 m/s (38,386 ft/min)

Armament

- Guns: 2× 30 mm Type 30-1 cannon, 60 rounds per gun

- Hardpoints: 5 in total - 4× under-wing, 1× centreline under-fuselage with a capacity of 2,000 kg maximum (up to 500 kg each)[45]

- Rockets: 55 mm rocket pod (12 rounds), 90 mm rocket pod (7 rounds)

- Missiles:

- Bombs: 50 kg to 500 kg unguided bombs

Avionics

- FIAR Grifo-7 mk.II radar

Significant losses

Flying officer Marium Mukhtiar, the first female fighter pilot in the Pakistan Air Force, died on 24 November 2015 when a twin-seat FT-7PG crashed at PAF Base M.M. Alam near Kundian in Punjab province on a training mission. Both pilots ejected, but she succumbed to injuries received on landing. It is not known whether she was occupying the front or rear seat during the training mission; front as trainee pilot-in-command, or rear for Instrument Flight Rules training. Pakistan's F-7 fighters are fitted with the Martin-Baker Mk.10 zero-zero ejection seat, however these are rated for level flight/ground and a rate of descent raises the safe operating limit. [46]

See also

- Related development

References

- Citations

- ↑ J7, Sino Defence.

- ↑ Medeiros 2005, p. 162.

- ↑ "China’s Expert Fighter Designer Knows Jets, Avoids America’s Mistakes". International Relations and Security Network. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ↑ Coatepeque. "China Defense Blog". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 Transfers of major conventional weapons. 1950 to 2011. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

- ↑ Jane's Defence Weekly; 21 January 2009, Vol. 46 Issue 3, p16-16

- ↑ "Zaire/DR Congo since 1980". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ http://www.dutchaviationsupport.com/Articles/Titana%20UK.pdf

- ↑ "People's Daily Online - Iranian military plane crashes in northeastern province:report". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ The MIG27 affair - Fighter Pilots reveal what the "defence analysts" forgot to tell, Sri Lanka Ministry of Defence

- ↑ DefenceNet. "DefenceNet: Defence News from Sri Lanka". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Indiandefenceforum.com". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Dailymirror.lk Archived September 15, 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Jian-7 Interceptor Fighter". - SinoDefence.com. 25 December 2008. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ↑ Gordon and Komissarov 2008, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ "J-7I Fighter Intercept USAF UAVs". - AirForceWorld.com. 2 Sep 2011.

- ↑ Archived May 7, 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "J-7IIH and PL-8 air-to-air missile". AirForceWorld.com. Retrieved 15 Aug 2011.

- 1 2 J-7C/D All-Weather Fighter - SinoDefence.com

- 1 2 J-7E, J-7G, F-7MG - SinoDefence.com

- ↑ J-7FS Technology Demonstration Aircraft - SinoDefence.com Archived May 10, 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 John Pike. "J-7 (Jianjiji-7 Fighter aircraft 7) / F-7". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ JJ-7 (FT-7) Fighter-Trainer - SinoDefence.com

- ↑ "JL-1". SinoDefence. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Doubts Cast on Supposed Zimbabwean Fighter Order from China (November 2004)

- ↑ "中华网--中华军事--中国图像式头盔瞄准具[图]". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "The AMR Regional Air Force Directory 2012" (PDF). Asian Military Review. February 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ↑ Hacket 2010, p. 250

- ↑ Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 40.

- ↑ Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 43.

- ↑ Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 44.

- ↑ "PAF s' Squadrons". paffalcons.com. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ Allport, Dave (28 April 2014). "First Five ex-Jordanian F-16s Delivered to Pakistan AF". airforcesdaily.com. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ Chaudhry, Asif Bashir (28 April 2014). "5 used Jordanian F-16s inducted into PAF". The Nation (Pakistan). Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ "JF-17 Thunder aircraft inducted into PAF Combat Commanders’ School". The News International. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ↑ Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 47.

- ↑ Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 48.

- ↑ IHS Jane's Defence Weekly, vol 50, issue 47 (Nov 20, 2013), page 21: Tanzania swaps old J-7-s for new ones

- ↑ Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 53.

- ↑ Historical Listings

- ↑ World Air Forces

- ↑ "Chengdu F-7A/MiG-21F-13, Rinas AFB, Albania". YouTube. 31 December 1969. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Sweetman, Bill (7 August 2012). "We didn’t know what 90 percent of the switches did". aviationweek.com/blog. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ↑ Jackson 2003, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Sinodefence.com

- ↑ Pakistan's First Female Fighter Pilot Killed in Trainer Crash, Usman Ansari, DefenseNews.com, 24 November 2015

- Bibliography

- Gordon, Yefim and Dmitry Komissarov. Chinese Aircraft: China's Aviation Industry since 1951. Manchester, UK: Hikoki Publications, 2008. ISBN 978-1-902109-04-6.

- Hacket, James, ed. (2010), "The Military Balance 2010", International Institute for Strategic Studies Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Jackson, Paul. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group, 2003. ISBN 0-7106-2537-5.

- Medeiros, Evan S., Roger Cliff, Keith Crane and James C. Mulvenon. A New Direction for China's Defense Industry. Rand Corporation, 2005. ISBN 0-83304-079-0.

- "World Air Forces". Flight International, 14–20 December 2010. pp. 26–53.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chengdu J-7. |

- F-7 Fighter Jet Family

- FT-7/JJ-7 Trainer Jet

- F-7BG

- F-7MB

- Bangladesh Air Force F-7MB & F-7BG Photo Gallery

- Technical Data from MiG-21.de

- Globalsecurity.org

- Sino Defense Today

- J-7/F-7 Fighter Aircraft Images

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||