Chemical potential

In thermodynamics, chemical potential, also known as partial molar free energy, is a form of potential energy that can be absorbed or released during a chemical reaction. It may also change during a phase transition. The chemical potential of a species in a mixture can be defined as the slope of the free energy of the system with respect to a change in the number of moles of just that species. Thus, it is the partial derivative of the free energy with respect to the amount of the species, all other species' concentrations in the mixture remaining constant, and at constant temperature. When pressure is constant, chemical potential is the partial molar Gibbs free energy. At chemical equilibrium or in phase equilibrium the total sum of chemical potentials is zero, as the free energy is at a minimum.[1][2][3]

In semiconductor physics, the chemical potential of a system of electrons at a temperature of zero Kelvin is known as the Fermi energy.[4]

Overview

Particles tend to move from higher chemical potential to lower chemical potential. In this way, chemical potential is a generalization of "potentials" in physics such as gravitational potential. When a ball rolls down a hill, it is moving from a higher gravitational potential (higher elevation) to a lower gravitational potential (lower elevation). In the same way, as molecules move, react, dissolve, melt, etc., they will always tend naturally to go from a higher chemical potential to a lower one, changing the particle number, which is conjugate variable to chemical potential.

A simple example is a system of dilute molecules diffusing in a homogeneous environment. In this system, the molecules tend to move from areas with high concentration to low concentration, until eventually the concentration is the same everywhere.

The microscopic explanation for this is based in kinetic theory and the random motion of molecules. However, it is simpler to describe the process in terms of chemical potentials: For a given temperature, a molecule has a higher chemical potential in a higher-concentration area, and a lower chemical potential in a low concentration area. Movement of molecules from higher chemical potential to lower chemical potential is accompanied by a release of free energy. Therefore it is a spontaneous process.

Another example, not based on concentration but on phase, is a glass of liquid water with ice cubes in it. Above 0°C, an H2O molecule that is in the liquid phase (liquid water) has a lower chemical potential than a water molecule that is in the solid phase (ice). When some of the ice melts, H2O molecules convert from solid to liquid where their chemical potential is lower, so the ice cubes shrink. Below 0°C, the molecules in the ice phase have the lower chemical potential, so the ice cubes grow. At the temperature of the melting point, 0°C, the chemical potentials in water and ice are the same; the ice cubes neither grow nor shrink, and the system is in equilibrium.

A third example is illustrated by the chemical reaction of dissociation of a weak acid, such as acetic acid, HA, A=CH3COO−.

- HA

H+ + A−

H+ + A−

Vinegar contains acetic acid. When acid molecules dissociate, the concentration of the undissociated acid molecules (HA) decreases and the concentrations of the product ions (H+ and A−) increase. Thus the chemical potential of HA decreases and the sum of the chemical potentials of H+ and A− increases. When the sums of chemical potential of reactants and products are equal the system is at equilibrium and there is no tendency for the reaction to proceed in either the forward or backward direction. This explains why vinegar is acidic, because acetic acid dissociates to some extent, releasing hydrogen ions into the solution.

Chemical potentials are important in many aspects of equilibrium chemistry, including melting, boiling, evaporation, solubility, osmosis, partition coefficient, liquid-liquid extraction and chromatography. In each case there is a characteristic constant which is a function of the chemical potentials of the species at equilibrium.

In electrochemistry, ions do not always tend to go from higher to lower chemical potential, but they do always go from higher to lower electrochemical potential. The electrochemical potential completely characterizes all of the influences on an ion's motion, while the chemical potential includes everything except the electric force. (See below for more on this terminology.)

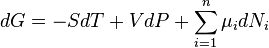

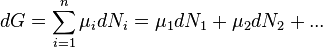

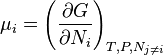

Thermodynamic definitions

The fundamental equation of chemical thermodynamics for a system containing n constituent species, with the i-th species having Ni particles is, in terms of Gibbs energy

At constant temperature and pressure this simplifies to

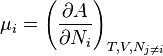

The definition of chemical potential of the i-th species, μi, follows by setting all the numbers Nj, apart from Ni, to be constant.

When temperature and volume are taken to be constant chemical potential relates to the Helmholtz free energy, A.

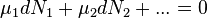

The chemical potential of a species is the slope of the free energy with respect to the number of particles of that species. It reflects the change in free energy when the number of particles of one species changes. Each chemical species, be it an atom, ion or molecule, has its own chemical potential. At equilibrium free energy is at its minimum for the system, that is, dG=0. It follows that the sum of chemical potentials is also zero.

Use of this equality provides the means to establish the equilibrium constant for a chemical reaction.

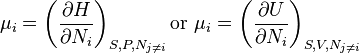

Other expressions are sometimes used.

.

.

Here U is internal energy, H is enthalpy and the entropy, S, is taken to be constant (see #History). Keeping the entropy fixed requires perfect thermal insulation, so these definitions have limited practical applications. The various expressions for chemical potential are related to each other by Legendre transformations.

Dependence on concentration (particle number)

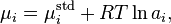

The variation of chemical potential with particle number is most easily expressed in terms relating quantities to their concentrations. The concentration of a species in a given volume, V, is simply Ni / V, so chemical potential can be defined in terms of concentration rather than particle number. For species in solution

where μistd is the potential in a given standard state and ai is the activity of the species in solution. Activity can be expressed as a product of concentration and an activity coefficient, so if activity coefficients are ignored, chemical potential is proportional to the logarithm of the concentration of the species.

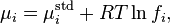

For species in the gaseous state the variation is expressed as

where fi is the fugacity. If the ideal gas law applies, fugacity is equal to partial pressure and chemical potential is proportional to the logarithm of the partial pressure.

Dependence on temperature and pressure

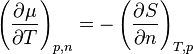

The Maxwell relation

shows that the temperature variation of chemical potential depends on entropy. If entropy increases as the particle number increases, then chemical potential will decrease as temperature increases.

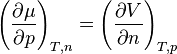

Similarly

shows that the pressure coefficient depends on volume. If volume increases with particle number, chemical potential also increases as pressure increases.

Applications

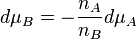

The Gibbs–Duhem equation is useful because it relates individual chemical potentials. For example, in a binary mixture, at constant temperature and pressure, the chemical potentials of the two participants are related by

Every instance of phase or chemical equilibrium is characterized by a constant. For instance, the melting of ice is characterized by a temperature, known as the melting point at which solid and liquid phases are in equilibrium with each other. Chemical potentials can be used to explain the slopes of lines on a phase diagram by using the Clapeyron equation, which in turn can be derived from the Gibbs–Duhem equation.[5] They are used to explain colligative properties such as melting-point depression by the application of pressure.[6] Both Raoult's law and Henry's law can be derived in a simple manner using chemical potentials.[7]

History

Chemical potential was first described by the American engineer, chemist and mathematical physicist Josiah Willard Gibbs. He defined it as follows:

If to any homogeneous mass in a state of hydrostatic stress we suppose an infinitesimal quantity of any substance to be added, the mass remaining homogeneous and its entropy and volume remaining unchanged, the increase of the energy of the mass divided by the quantity of the substance added is the potential for that substance in the mass considered.

Gibbs later noted also that for the purposes of this definition, any chemical element or combination of elements in given proportions may be considered a substance, whether capable or not of existing by itself as a homogeneous body. This freedom to choose the boundary of the system allows chemical potential to be applied to a huge range of systems. The term can be used in thermodynamics and physics for any system undergoing change. Chemical potential is also referred to as partial molar Gibbs energy (see also partial molar property). Chemical potential is measured in units of energy/particle or, equivalently, energy/mole.

In his 1873 paper A Method of Geometrical Representation of the Thermodynamic Properties of Substances by Means of Surfaces, Gibbs introduced the preliminary outline of the principles of his new equation able to predict or estimate the tendencies of various natural processes to ensue when bodies or systems are brought into contact. By studying the interactions of homogeneous substances in contact, i.e. bodies, being in composition part solid, part liquid, and part vapor, and by using a three-dimensional volume–entropy–internal energy graph, Gibbs was able to determine three states of equilibrium, i.e. "necessarily stable", "neutral", and "unstable", and whether or not changes will ensue. In 1876, Gibbs built on this framework by introducing the concept of chemical potential so to take into account chemical reactions and states of bodies that are chemically different from each other. In his own words, to summarize his results in 1873, Gibbs states:

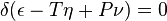

If we wish to express in a single equation the necessary and sufficient condition of thermodynamic equilibrium for a substance when surrounded by a medium of constant pressure P and temperature T, this equation may be written:

where δ refers to the variation produced by any variations in the state of the parts of the body, and (when different parts of the body are in different states) in the proportion in which the body is divided between the different states. The condition of stable equilibrium is that the value of the expression in the parenthesis shall be a minimum.

In this description, as used by Gibbs, ε refers to the internal energy of the body, η refers to the entropy of the body, and ν is the volume of the body.

Electrochemical, internal, external, and total chemical potential

The abstract definition of chemical potential given above—total change in free energy per extra mole of substance—is more specifically called total chemical potential.[8][9] If two locations have different total chemical potentials for a species, some of it may be due to potentials associated with "external" force fields (Electric potential energy differences, gravitational potential energy differences, etc.), while the rest would be due to "internal" factors (density, temperature, etc.)[8] Therefore the total chemical potential can be split into internal chemical potential and external chemical potential:

where

i.e., the external potential is the sum of electric potential, gravitational potential, etc. (q and m are the charge and mass of the species, respectively, V and h are the voltage and height of the container, respectively, and g is the acceleration due to gravity.) The internal chemical potential includes everything else besides the external potentials, such as density, temperature, and enthalpy.

The phrase "chemical potential" sometimes means "total chemical potential", but that is not universal.[8] In some fields, in particular electrochemistry, semiconductor physics, and solid-state physics, the term "chemical potential" means internal chemical potential, while the term electrochemical potential is used to mean total chemical potential.[10][11][12][13][14]

Systems of particles

Chemical potential of electrons

Electrons in solids have a chemical potential, defined the same way as the chemical potential of a chemical species: The change in free energy when electrons are added or removed from the system. In the case of electrons, the chemical potential is usually expressed in energy per particle rather than energy per mole, and the energy per particle is conventionally given in units of electron-volt (eV).

Chemical potential plays an especially important role in solid-state physics and is closely related to the concepts of work function, Fermi energy, and Fermi level. For example, n-type silicon has a higher internal chemical potential of electrons than p-type silicon. In a p–n junction diode at equilibrium the chemical potential (internal chemical potential) varies from the p-type to the n-type side, while the total chemical potential (electrochemical potential, or, Fermi level) is constant throughout the diode.

As described above, when describing chemical potential, one has to say "relative to what". In the case of electrons in semiconductors, internal chemical potential is often specified relative to some convenient point in the band structure, e.g., the to bottom of the conduction band. It may also be specified "relative to vacuum", to yield a quantity known as work function, however work function varies from surface to surface even on a completely homogeneous material. Total chemical potential on the other hand is usually specified relative to electrical ground.

In atomic physics, the chemical potential of an atom is sometimes said to be the negative of the atom's electronegativity. Likewise, the process of chemical potential equalization is sometimes referred to as the process of electronegativity equalization. This connection comes from the Mulliken electronegativity scale. By inserting the energetic definitions of the ionization potential and electron affinity into the Mulliken electronegativity, it is seen that the Mulliken chemical potential is a finite difference approximation of the electronic energy with respect to the number of electrons., i.e.,

where IP and EA are the ionization potential and electron affinity of the atom, respectively.

Sub-nuclear particles

In recent years, thermal physics has applied the definition of chemical potential to systems in particle physics and its associated processes. For example, in a quark–gluon plasma or other QCD matter, at every point in space there is a chemical potential for photons, a chemical potential for electrons, a chemical potential for baryon number, electric charge, and so forth.

In the case of photons, photons are bosons and can very easily and rapidly appear or disappear. Therefore the chemical potential of photons is always and everywhere zero. The reason is, if the chemical potential somewhere was higher than zero, photons would spontaneously disappear from that area until the chemical potential went back to zero; likewise if the chemical potential somewhere was less than zero, photons would spontaneously appear until the chemical potential went back to zero. Since this process occurs extremely rapidly (at least, it occurs rapidly in the presence of dense charged matter), it is safe to assume that the photon chemical potential is never different from zero.

Electric charge is different, because it is conserved, i.e. it can be neither created nor destroyed. It can, however, diffuse. The "chemical potential of electric charge" controls this diffusion: Electric charge, like anything else, will tend to diffuse from areas of higher chemical potential to areas of lower chemical potential.[15] Other conserved quantities like baryon number are the same. In fact, each conserved quantity is associated with a chemical potential and a corresponding tendency to diffuse to equalize it out.[16]

In the case of electrons, the behavior depends on temperature and context. At low temperatures, with no positrons present, electrons cannot be created or destroyed. Therefore there is an electron chemical potential that might vary in space, causing diffusion. At very high temperatures, however, electrons and positrons can spontaneously appear out of the vacuum (pair production), so the chemical potential of electrons by themselves becomes a less useful quantity than the chemical potential of the conserved quantities like (electrons minus positrons).

The chemical potentials of bosons and fermions is related to the number of particles and the temperature by Bose–Einstein statistics and Fermi–Dirac statistics respectively.

See also

- Activity (chemistry)

- Chemical equilibrium

- Electrochemical potential

- Equilibrium chemistry

- Excess chemical potential

- Fugacity

- Partial molar property

- Thermodynamic equilibrium

References

- ↑ Atkins, Peter; de Paula, Julio (2006). Atkins' Physical Chemistry (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-870072-2. Page references in this article refer specifically to the 8th edition of this book.

- ↑ Baierlein, Ralph (April 2001). "The elusive chemical potential" (PDF). American Journal of Physics 69 (4): 423–434. Bibcode:2001AmJPh..69..423B. doi:10.1119/1.1336839.

- ↑ Job, G.; Herrmann, F. (February 2006). "Chemical potential–a quantity in search of recognition" (PDF). European Journal of Physics 27 (2): 353–371. Bibcode:2006EJPh...27..353J. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/27/2/018.

- ↑ Kittel, Charles; Herbert Kroemer (1980-01-15). Thermal Physics (2nd Edition). W. H. Freeman. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-7167-1088-2.

- ↑ Atkins, Section 4.1, p 126

- ↑ Atkins, Section 5.5, pp 150-155

- ↑ Atkins, Section 5.3, pp 143-145

- 1 2 3 Thermal Physics by Kittel and Kroemer, second edition, page 124.

- ↑ Thermodynamics in Earth and Planetary Sciences by Jibamitra Ganguly, google books link. This text uses "internal", "external", and "total chemical potential" as in this article.

- ↑ Electrochemical Methods by Bard and Faulkner, 2nd edition, Section 2.2.4(a),4-5.

- ↑ Electrochemistry at Metal and Semiconductor Electrodes, by Norio Sato, pages 4-5, google books link

- ↑ Physics Of Transition Metal Oxides, by Sadamichi Maekawa, p323, google books link

- ↑ The Physics of Solids: Essentials and Beyond, by Eleftherios N. Economou, page 140, google books link. In this text, total chemical potential is usually called "electrochemical potential", but sometimes just "chemical potential". The internal chemical potential is referred to by the unwieldy phrase "chemical potential in the absence of the [electric] field".

- ↑ Solid State Physics by Ashcroft and Mermin, page 257 note 36. Page 593 of the same book uses, instead, an unusual "flipped" definition where "chemical potential" is the total chemical potential which is constant in equilibrium, and "electrochemical potential" is the internal chemical potential; presumably this unusual terminology was an unintentional mistake.

- ↑ Baierlein, Ralph (2003). Thermal Physics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65838-1. OCLC 39633743.

- ↑ Hadrons and Quark-Gluon Plasma, by Jean Letessier, Johann Rafelski, p91

External links

- Chemical Potential

- Chemical Potentials

- Values of the chemical potential of 1300 substances

- G. Cook and R. H. Dickerson "Understanding the chemical potential", American Journal of Physics 63 pp. 737-742 (1995)

- T. A. Kaplan "The Chemical Potential", Journal of Statistical Physics 122 pp. 1237-1260 (2006)

![\mu_{\mathrm{Mulliken}}=-\chi_{\mathrm{Mulliken}}=-\frac{IP+EA}{2}=\left[\frac{\delta E[N]}{\delta N}\right]_{N=N_0}](../I/m/d0ad966d69609202f1584b44f0f272f5.png)