Charles XIV John of Sweden

| Charles XIV & III John | |

|---|---|

Charles XIV John (King of Sweden and Norway). Painting by François Gérard | |

| King of Sweden and Norway | |

| Reign | 5 February 1818 – 8 March 1844 |

| Coronations |

11 May 1818 (Sweden) 7 September 1818 (Norway) |

| Predecessor | Charles XIII/II |

| Successor | Oscar I |

| Born |

26 January 1763 Pau, France |

| Died |

8 March 1844 (aged 81) Stockholm, Sweden |

| Burial | Riddarholmskyrkan, Stockholm |

| Spouse |

Désirée Clary (m. 1798; his death 1844) |

| Issue | Oscar I |

| House | Bernadotte |

| Father | Henri Bernadotte |

| Mother | Jeanne de Saint-Jean |

| Religion |

Church of Sweden prev. Roman Catholicism |

| Signature |

|

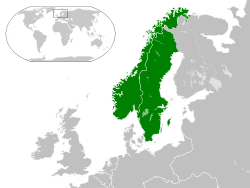

Charles XIV & III John, also Carl John, Swedish and Norwegian: Karl Johan (26 January 1763 – 8 March 1844) was King of Sweden (as Charles XIV John) and King of Norway (as Charles III John) from 1818 until his death and served as de facto regent and head of state from 1810 to 1818. When he became Swedish royalty, he had also been the Sovereign Prince of Pontecorvo in Central-Southern Italy from 1806 until 1810[1] (title established on June 5, 1806 by Napoleon), but then stopped using that title.

He was born Jean Bernadotte[2] and subsequently had acquired the full name of Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte[3] by the time Carl also was added upon his Swedish adoption in 1810. He did not use Bernadotte in Sweden but founded the royal dynasty there by that name.

French by birth, Bernadotte served a long career in the French Army. He was appointed as a Marshal of France by Napoleon I, though the two had a turbulent relationship. His service to France ended in 1810, when he was elected the heir-presumptive to the Swedish throne because the Swedish royal family was dying out with King Charles XIII. Baron Carl Otto Mörner (22 May 1781 – 17 August 1868), a Swedish courtier and obscure member of the Riksdag of the Estates, advocated for the succession.[4]

Early life and family

Bernadotte was born in Pau, France, as the son of Jean Henri Bernadotte (Pau, Béarn, 14 October 1711 – Pau, 31 March 1780), prosecutor at Pau, and wife (married at Boeil, 20 February 1754) Jeanne de Saint-Jean (Pau, 1 April 1728 – Pau, 8 January 1809), niece of the Lay Abbot of Sireix. The family name was originally du Poey (or de Pouey), but was changed to Bernadotte – a surname of an ancestress – at the beginning of the 17th century.[5] Bernadotte himself added Jules to his first names later.[5]

Military career

| Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Marshal Bernadotte, Prince de Ponte-Corvo. Painted by Joseph Nicolas Jouy, after François-Joseph Kinson | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Years of service | 1780 - 1810 |

| Rank | Marshal of the Empire |

| Commands held | Governor of Hanover |

| Battles/wars |

French Revolutionary Wars Napoleonic Wars |

| Awards |

Legion of Honour Names inscribed under the Arc de Triomphe Titled Prince of Ponte-Corvo |

| Other work |

Minister of War Councillor of State |

Bernadotte joined the army as a private in the Régiment de Royal-Marine on 3 September 1780, and first served in the newly conquered territory of Corsica.[5] Following the outbreak of the French Revolution, his eminent military qualities brought him speedy promotion.[5] He was promoted by 1794 brigadier, attached to the Army of Sambre-et-Meuse.[5] After Jourdan's victory at Fleurus (26 June 1794) he became a general of division. At the Battle of Theiningen (1796), Bernadotte contributed, more than anyone else, to the successful retreat of the French army over the Rhine after its defeat by the Archduke Charles of Austria. In 1797 he brought reinforcements from the Rhine to Bonaparte's army in Italy, distinguishing himself greatly at the passage of the Tagliamento, and in 1798 served as ambassador to Vienna, but had to quit his post owing to the disturbances caused by his hoisting the tricolour over the embassy.[5]

From 2 July to 14 September he was Minister of War, in which capacity he displayed great ability. He declined to help Napoleon Bonaparte stage his coup d'état of November 1799, but nevertheless accepted employment from the Consulate, and from April 1800 to 18 August 1801 commanded the army in the Vendée.[5]

On the introduction of the First French Empire, Bernadotte became one of the eighteen Marshals of the Empire and, from June 1804 to September 1805, served as governor of the recently occupied Hanover. During the campaign of 1805, Bernadotte with an army corps from Hanover, co-operated in the great movement which resulted in the shutting off of Mack in Ulm. As a reward for his services at Austerlitz (2 December 1805) he became the 1st Sovereign Prince of Ponte Corvo (5 June 1806), but during the campaign against Prussia, in the same year, was severely reproached by Napoleon for not participating with his army corps in the battles of Jena and Auerstädt, though close at hand.[6]

In 1808, as governor of the Hanseatic towns, he was to have directed the expedition against Sweden, via the Danish islands, but the plan came to naught because of the want of transports and the defection of the Spanish contingent. In the war against Austria, Bernadotte led the Saxon contingent at the Battle of Wagram (6 July 1809), on which occasion, on his own initiative, he issued an Order of the Day attributing the victory principally to the valour of his Saxons, which order Napoleon at once disavowed.[6] It was during the middle of that battle that Marshal Bernadotte was stripped of his command after retreating contrary to Napoleon's orders. Napoleon remarked on St. Helena, "I can accuse him of ingratitude but not treachery".[7]

Conspiracy of Rennes/Plot of Placards & the Governor of Louisiana

Bernadotte was one of the worst malcontents in the French general staff, and this was well known to Napoleon. In the early summer of 1802, Bernadotte's chief-of-staff was caught leading a conspiracy to whip up a revolt among the large numbers of troops that were being concentrated in Rennes, Brittany. These conscripts were soon to be dispatched to the West Indies, where it was well known that most Europeans were dying from Yellow Fever. Though the plot was uncovered before much more had been achieved than the distribution of seditious handbills and placards, it had still been frightening enough for Napoleon; he initially threatened to have Bernadotte shot, but he wisely backed away after Joseph Bonaparte, Bernadotte's brother-in-law, successfully convinced his younger brother that there was no evidence directly linking Bernadotte with the conspiracy. Nevertheless, Bernadotte remained persona non grata at the Consulate and kept a low profile by residing in Plombières-les-Bains.

In September 1802, Napoleon considered who would make a suitable governor for the retrocession of Louisiana, effective on 15 October 1802. Bernadotte seemed to be the perfect candidate for this virtual exile; he accepted, and he and his family made preparations to depart from La Rochelle. On the day of Bernadotte's scheduled departure, April 12, 1803, James Monroe arrived in Paris to close the deal on the Louisiana Purchase. When Bernadotte's party arrived in La Rochelle, confusion ensued for many days as the ship charted to take them to Louisiana was counter-ordered to carry General Jean Augustin Ernouf to his appointment of governor general of the French colony in Saint-Domingue and Guadeloupe following the suppression of a sudden widespread slave insurrection. A second possible ship was recalled to convey supplies to the army in Saint Domingue. While organizing a third vessel to take him to Louisiana, Parisian newspapers had reached Bernadotte announcing the surprise conclusion of the Louisiana Purchase. Bernadotte was waiting in La Rochelle for clarification from the Consulate on May 16, when Britain declared war on France. On May 27, Bernadotte sent a letter to Napoleon through Joseph resigning his Louisianan appointment and asking for an army for the impending War of the Third Coalition. Under pressure from Joseph, Napoleon acquiesced, but still did not send orders to Bernadotte for over a year.[7]

Offer of the Swedish throne

Bernadotte, considerably piqued, returned to Paris where the council of ministers entrusted him with the defence of the Netherlands against the British expedition in Walcheren. In 1810, he was about to enter upon his new post as governor of Rome when he was unexpectedly elected the heir-presumptive to King Charles XIII of Sweden.[6] The problem of Charles' successor had been acute almost from the time he had ascended the throne a year earlier, as it was apparent that the Swedish branch of the House of Holstein-Gottorp would die with him. He was 61 years old and in failing health. He was also childless; Queen Charlotte had given birth to two children who had died in infancy, and there was no prospect of her bearing another child. The king had adopted a Danish prince, Charles August, as his son soon after his coronation, but he had died just a few months after his arrival.[8]

Bernadotte was elected partly because a large part of the Swedish Army, in view of future complications with Russia, were in favour of electing a soldier, and partly because he was also personally popular, owing to the kindness he had shown to the Swedish prisoners during the recent war with Denmark.[6] The matter was decided by one of the Swedish courtiers, Baron Karl Otto Mörner, who, entirely on his own initiative, offered the succession to the Swedish crown to Bernadotte. Bernadotte communicated Mörner's offer to Napoleon, who treated the whole affair as an absurdity. The Emperor did not support Bernadotte but did not oppose him either and so Bernadotte informed Mörner that he would not refuse the honour if he were elected. Although the Swedish government, amazed at Mörner's effrontery, at once placed him under arrest on his return to Sweden, the candidature of Bernadotte gradually gained favour and on 21 August 1810[6] he was elected by the Riksdag of the Estates to be the new Crown Prince,[6] and was subsequently made Generalissimus of the Swedish Armed Forces by the King.[9]

Before freeing Bernadotte from his allegiance to France, Napoleon asked him to agree never to take up arms against France. Bernadotte having refused to make any such agreement, upon the ground that his obligations to Sweden would not allow it, Napoleon exclaimed “Go, and let our destinies be accomplished” and signed the act of emancipation unconditionally.[10]

Crown Prince and Regent

Painting by Fredric Westin.

On 2 November Bernadotte made his solemn entry into Stockholm, and on 5 November he received the homage of the Riksdag of the Estates, and he was adopted by King Charles XIII under the name of "Charles John" (Karl Johan).[6] At the same time, he converted from Roman Catholicism to the Lutheranism of the Swedish court.[11]

“I have beheld war near at hand, and I know all its evils: for it is not conquest which can console a country for the blood of her children, spilt on a foreign land. I have seen the mighty Emperor of the French, so often crowned with the laurel of victory, surrounded by his invincible armies, sigh after the olive-branches of peace. Yes, Gentlemen, peace is the only glorious aim of a sage and enlightened government: it is not the extent of a state which constitutes its strength and independence; it is its laws, its commerce, its industry, and above all, its national spirit.”

The new Crown Prince was very soon the most popular and most powerful man in Sweden. The infirmity of the old King and the dissensions in the Privy Council of Sweden placed the government, and especially the control of foreign policy, entirely in his hands. The keynote of his whole policy was the acquisition of Norway as a compensation for the loss of Finland and Bernadotte proved anything but a puppet of France. [6] Many Swedes expected him to reconquer Finland which had been ceded to Russia, however, the Crown Prince was aware of its difficulty for reasons of the desperate situation of the state finance and the lack of the Finnish people to accept their return to Sweden. [13] Even if Finland was regained, he thought, it would put Sweden into a cycle of conflicts with the powerful neighbor because there was no guarantee Russia would accept the loss as final. [14]Therefore, he made up his mind to make a united Scandinavia peninsula by taking Norway from Denmark and uniting her to Sweden. He tried to divert public opinion from Finland to Norway, by arguing that to create a compact peninsula, with sea for its natural boundary, was to inaugurate an era of peace, and that to establish a state of war with Russia would lead to ruinous consequences.[15]

Soon after Charles John’s arrival in Sweden, Napoleon compelled him to accede to the continental system and declare war against Great Britain; otherwise, Sweden would have to face the determination of France, Denmark and Russia.This demand would mean a hard blow to the national economy and the Swedish population. Sweden reluctantly declared war against Great Britain but it was treated by both countries as being merely nominal, although Swedish imports of British goods decreased from £4,871 million in 1810 to £523 million in the following year. [16][17]

Suddenly French troops in January, 1812, invaded Swedish Pomerania and the island of Rügen.[18] The decisive reason was that Napoleon, before marching to Moscow, had to secure his rear and dared not trust a Swedish continental foothold behind him.[19] The invasion was a clear violation of international law as well as an act of war so that public opinion in Sweden was understandably outraged.[19][20] Moreover, it antagonized the pro-French faction at the Swedish court.[21] Thereafter, the Crown Prince declared the neutrality of Sweden and opened negotiations with Great Britain and Russia.[22]

In 1813 he allied Sweden with Napoleon's enemies, including Great Britain, Russia and Prussia, in the Sixth Coalition, hoping to secure Norway. After the defeats at Lützen (2 May 1813) and Bautzen (21 May 1813), it was the Swedish Crown Prince who put fresh fighting spirit into the Allies; and at the conference of Trachenberg he drew up the general plan for the campaign which began after the expiration of the Truce of Pläswitz.[6]

Charles John, as the Commander-in-Chief of the Northern Army, successfully defended the approaches to Berlin and was victorious in battle against Oudinot in August and against Ney in September at the Battles of Großbeeren and Dennewitz; but after the Battle of Leipzig he went his own way, determined at all hazards to cripple Denmark and to secure Norway,[6] defeating the Danes in a relatively quick campaign. His efforts culminated in the favourable Treaty of Kiel, which transferred Norway to Swedish control.[11]

However, the Norwegians were unwilling to accept Swedish overlordship. They declared independence, adopted a liberal constitution and elected Danish crown prince Christian Frederick to the throne. The ensuing war was swiftly won by Sweden under Charles John's generalship. Charles John could have named his terms to Norway, but in a key concession accepted the Norwegian constitution.[11][23] This paved the way for Norway to enter a personal union with Sweden later that year.[6]

King of Sweden and Norway

As the union King, Charles XIV John in Sweden and Charles III John in Norway, who succeeded to that title on 5 February 1818 following the death of Charles XIII & II, he was initially popular in both countries.[6]

The foreign policy applied by Charles John in the post-Napoleonic era was characterized by the maintenance of balance between the Great Powers and non-involvement into conflicts that took place outside of the Scandinavian peninsula, and he successfully kept his kingdoms in state of peace from 1814 until his death. [24][11] He was especially concerned about the conflict between Great Britain and Russia. In 1834, when the relationship between both countries strained regarding the Near East Crisis, he sent memorandum to British and Russian governments and proclaimed neutrality in advance. It is pointed out as the origin of Swedish neutrality.[25]

His domestic policy particularly focused on promotion of economy and investment in social overhead capital, and the long peace since 1814 led to an increased prosperity for the country.[26] During his long reign of 26 years, the population of the Kingdom was so much increased that the inhabitants of Sweden alone became equal in number to those of Sweden and Finland before the latter province was torn from the former, the national debt was paid off, a civil and a penal code were proposed for promulgation, education was promoted, agriculture, commerce, and manufactures prospered, and the means of internal communication were increased.[26][27]

On the other hand, radical in his youth, his views had veered steadily rightward over the years, and by the time he ascended the throne he was an ultra-conservative. His autocratic methods, particularly his censorship of the press, were very unpopular, especially after 1823. However, his dynasty never faced serious danger, as the Swedes and the Norwegians alike were proud of a monarch with a good European reputation.[11] [6]

He also faced challenges in Norway. The Norwegian constitution gave the Norwegian parliament, the Storting, more power than any legislature in Europe. While Charles John had the power of absolute veto in Sweden, he only had a suspensive veto in Norway. He demanded that the Storting give him the power of absolute veto, but was forced to back down.[23]

Opposition to his rule reached a fever pitch in the 1830s, culminating in demands for his abdication.[11] Charles John survived the abdication controversy and he went on to have his silver jubilee, which was celebrated with great enthusiasm on 18 February 1843. He reigned as King of Sweden and Norway from 5 February 1818 until his death in 1844.[6]

Death

On 26 January 1844,[6] his 81st birthday, Charles John was found unconscious in his chambers having suffered a stroke. While he regained consciousness, he never fully recovered and died on the afternoon of 8 March. On his deathbed, he was heard to say:

"Nobody has had a career in life like mine.[26] I could perhaps have been able to agree to become Napoleon’s ally: but when he attacked the country that had placed its fate in my hands, he could find in me no other than an opponent. The events that shook Europe and that gave her back her freedom are known. It is also known which part I played in that."[28]

His remains were interred after a state funeral in Stockholm's Riddarholm Church.[29] He was succeeded by his only son, Oscar I.[30]

Titles, styles, honours, and arms

- 18 May 1804 - 26 September 1810: Jean Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, Marshal of France

- 5 June 1806 - 26 September 1810: Jean Baptiste Jules, Sovereign Prince of Pontecorvo

- 26 September 1810 - 5 November 1810: His Royal Highness Prince Johan Baptist Julius de Pontecorvo, Prince of Sweden[31]

- 5 November 1810[6] - 4 November 1814: His Royal Highness Charles John, Crown Prince of Sweden

- 4 November 1814[6] - 5 February 1818: His Royal Highness Charles John, Crown Prince of Sweden and Norway

- 5 February 1818 - 8 March 1844: His Majesty the King of Sweden and Norway.

Honours

King Charles John was the 909th Knight of the Order of the Golden Fleece in Spain and the 28th Grand Cross of the Order of the Tower and Sword in Portugal.

- The main street of Oslo, Karl Johans gate, was named after him in 1852.

- The main base for the Royal Norwegian Navy, Karljohansvern, was also named after him in 1854.

- The Karlsborg Fortress (Swedish: Karlsborgs fästning), located in the present-day Karlsborg Municipality in Västra Götaland County, was also named in honour of him.

Arms

|

|

|

|

Fictional portrayals

The love triangle between Napoleon, Bernadotte and Desiree Clary was the subject of the novel Désirée, by Annemarie Selinko.

The novel was filmed as Désirée in 1954, with Marlon Brando as Napoleon, Jean Simmons as Désirée, and Michael Rennie as Bernadotte.

Bernadotte appears in a series of side missions in the video game Assassin's Creed Unity, again concerning the love triangle.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Charles XIV John of Sweden | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ↑ Palmer 1990, p. .

- ↑ Ulf Ivar Nilsson in Allt vi trodde vi visste men som faktiskt är FEL FEL FEL!, Bokförlaget Semic 2007 ISBN 978-91-552-3572-7 p 40

- ↑ Six 2003, p. .

- ↑ Cronholm 1902, pp. 249-71.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bain 1911, p. 931.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Bain 1911, p. 932.

- 1 2 Barton 1921.

- ↑ Charles XIII at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Ancienneté och Rang-Rulla öfver Krigsmagten år 1813 (in Swedish). 1813.

- ↑ Barton, Sir Dunbar Plunket (1930). P.245-246

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Charles XIV John at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Meredith, William George (1829). P.105-106

- ↑ Berdah, Jean-Francois (2009).P.39

- ↑ Palmer, Alan(1990). P.181

- ↑ Barton, Sir Dunbar Plunket (1930). P.257-258

- ↑ Berdah, Jean-Francois (2009).P.40-41

- ↑ Barton, Sir Dunbar Plunket (1930). P.259

- ↑ Barton, Sir Dunbar Plunket (1930). P.265

- 1 2 Scott, Franklin D.(1988). P.307

- ↑ Favier, Franck (2010). P.206-207

- ↑ Griffiths, Tony (2004). P.19

- ↑ Berdah, Jean-Francois (2009). P.45

- 1 2 Norway at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Killham, Edward L.(1993). P.17-19

- ↑ Wahlbäck, Krister(1986).P.7-12

- 1 2 3 Sjostrom, Olof

- ↑ Barton, Sir Dunbar Plunket (1930). P.374

- ↑ Alm, Mikael;Johansson, Brittinger(Eds) (2008).p.12

- ↑ Palmer 1911, p. 248.

- ↑ The American Cyclopædia (1879)

- ↑ Succession au trône de Suède: Acte d'élection du 21 août 1810, Loi de succession au trône du 26 septembre 1810 (in French)

References

- Alm, Mikael;Johansson, Brittinger(Eds) (2008). Script of Kingship:Essays on Bernadotte and Dynastic Formation in an Age of Revolution, Reklam & katalogtryck AB, Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-977312-2-5

- Barton, Sir Dunbar Plunket (1921). Bernadotte and Napoleon: 1763–1810. London: John Murray.

- Barton, Sir Dunbar Plunket (1930). The Amazing Career of Bernadotte 1763-1844, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

- Berdah, Jean-Francois (2009). “The Triumph of Neutrality : Bernadotte and European Geopolitics(1810-1844)”, Revue D’ Histoire Nordique, No.6-7.

- Cronholm, Neander N. (1902). "39". A History of Sweden from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. pp. 249–71.

- Favier, Franck (2010). Bernadotte: Un marechal d’empire sur le trone de Suede, Ellipses Edition Marketing, Paris. ISBN 9782340-006058

- Griffiths, Tony (2004). Scandinavia, C. Hurst & Co., London. ISBN 1-85065-317-8

- Killham, Edward L.(1993).The Nordic Way : A Path to Baltic Equilibrium, The Compass Press, Washington, DC. ISBN 0-929590-12-0

- Meredith, William George (1829). Memorials of Charles John, King of Sweden and Norway, Henry Colburn, London.

- Palmer, Alan (1990). Bernadotte : Napoleon’s Marshal, Sweden’s King, John Murray, London. ISBN 0-7195-4703-2

- Scott, Franklin D.(1988). Sweden, The Nation's History, Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale. ISBN 0-8093-1489-4

- Six, Georges (2003). Dictionnaire Biographique des Generaux & Amiraux Francais de la Revolution et de l'Empire (1792-1814). Paris: Gaston Saffroy.

- Sjostrom, Olof. "KARL XIV JOHAN" (PDF). Ambassade de France en Suede. Retrieved 2016-01-09.

- Wahlbäck, Krister(1986). The Roots of Swedish Neutrality, The Swedish Institute, Stockholm.

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). "Charles XIV.". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 931–932.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). "Charles XIV.". In Chisholm, Hugh. Encyclopædia Britannica 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 931–932. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Bernadotte, Jean Baptiste Jules". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Bernadotte, Jean Baptiste Jules". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

Further reading

- Alm, Mikael and Britt-Inger Johansson, eds. Scripts of Kingship: Essays on Bernadotte and Dynastic Formation in an Age of Revolution (Uppsala: Swedish Science Press, 2008)

- Review by Rasmus Glenthøj, English Historical Review (2010) 125#512 pp 205–208.

- Barton, Dunbar B.: The amazing career of Bernadotte, 1930; condensed one volume biography based on Barton's detailed 3 vol biography 1914-1925, which contained many documents

- Koht, Halvdan. "Bernadotte and Swedish-American Relations, 1810-1814," Journal of Modern History (1944) 16#4 pp. 265–285 in JSTOR

- Lord Russell of Liverpool: Bernadotte: Marshal of France & King of Sweden, 1981

- Jean-Marc Olivier. "Bernadotte Revisited, or the Complexity of a Long Reign (1810–1844)", in Nordic Historical Review, n°2, 2006.

- Scott, Franklin D. Bernadotte and the Fall of Napoleon (1935); scholarly analysis

- Moncure, James A. ed. Research Guide to European Historical Biography: 1450-Present (4 vol 1992); vol 1 pp 126–34

External links

-

Media related to Charles XIV John of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles XIV John of Sweden at Wikimedia Commons - "Marshal Bernadotte". The Napoleon Series.

-

"Charles XIV. John". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Charles XIV. John". New International Encyclopedia. 1905. -

"Bernadotte, Jean Baptiste Jules". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

"Bernadotte, Jean Baptiste Jules". The American Cyclopædia. 1879.

| Charles XIV/III John Born: 26 January 1763 Died: 8 March 1844 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Charles XIII/II |

King of Sweden and Norway 5 February 1818 – 8 March 1844 |

Succeeded by Oscar I |

| New title | Prince of Pontecorvo 5 June 1806 – 21 August 1810 |

Vacant Title next held by Lucien Murat |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Louis de Mureau |

Minister of War of France 2 July 1799 – 14 September 1799 |

Succeeded by Edmond Dubois-Crancé |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||

|

2.svg.png)

._D%C3%A9claration_des_Droits_et_des_Devoirs_de_l'Homme_et_du_Citoyen.jpg)