Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

| Charles William Ferdinand | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel | |||||

| |||||

| Reign | 26 March 1780 – 10 November 1806 | ||||

| Predecessor | Charles I | ||||

| Successor | Frederick William | ||||

| Born |

9 October 1735 Wolfenbüttel, Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel | ||||

| Died |

10 November 1806 (aged 71) Ottensen | ||||

| Consort |

Princess Augusta of Great Britain (m. 1764–1806; his death) | ||||

| Issue |

Augusta, Duchess of Württemberg Charles George Augustus, Hereditary Prince Duke George William Christian Duke Augustus Caroline, Queen of the United Kingdom Frederick William Duchess Amelia | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Brunswick-Bevern | ||||

| Father | Charles I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel | ||||

| Mother | Princess Philippine Charlotte of Prussia | ||||

Charles William Ferdinand (German: Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Fürst und Herzog von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel) (October 9, 1735 – November 10, 1806), Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, was a sovereign prince of the Holy Roman Empire, and a professional soldier who served as a Generalfeldmarschall of the Kingdom of Prussia. Born in Wolfenbüttel, Germany, he was duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel from 1780 until his death. He is a recognized master of the modern warfare of the mid-18th century, a cultured and benevolent despot in the model of Frederick the Great, and was married to Princess Augusta, a sister of George III of Great Britain. The botanical genus Brunsvigia was named in his honour.

Early life

Charles William Ferdinand (German: Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand) was the son of Charles I, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel and Philippine Charlotte, daughter of King Frederick William I of Prussia. Karl received an unusually wide and thorough education, and travelled in his youth in the Netherlands, France and various parts of Germany.

Initial military career

Charles William Ferdinand entered the military, serving during the Seven Years' War of 1756-63. He joined the allied north-German forces of the Hanoverian Army of Observation, whose task was to protect Hanover (a British ally) and the surrounding states from invasion by the French. The force was initially commanded by the Hanoverian Prince William, Duke of Cumberland.[1] At the Battle of Hastenbeck Charles William Ferdinand led a charge at the head of an infantry brigade, an action which gained him some renown.[1][2]

The subsequent French Invasion of Hanover and Convention of Klosterzeven of 1757 temporarily knocked Hanover out of the war (they were to return the following year). Charles William Ferdinand was easily persuaded to continue his military service as a general officer by his uncle Ferdinand of Brunswick, who replaced Cumberland in command of the remaining allied north-German forces.[2] Charles William Ferdinand's reputation continued to improve, and he became an acknowledged master of irregular warfare.[2]

He was part of the allied Anglo-German force at the Battle of Minden (1759), and the Battle of Warburg (1760). Both were decisive victories over the French, during which he proved himself an excellent subordinate commander.[2] He continued to serve in the army commanded by his uncle for the remainder of the war, which was generally successful for the north German forces. Peace was restored in 1763.

He was made a Prussian general in 1773.

From 1778-79 he served in the War of the Bavarian Succession.[2]

Ruler of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

His father, Charles I, had been an enthusiastic supporter of the war, but nearly bankrupted the state paying for it. As a result, in 1773 Charles William Ferdinand was given a major role in reforming the economy. With the assistance of the minister Feonçe von Rotenkreuz he was highly successful, restoring the state's finances and improving the economy. This made him hugely popular in the duchy.[2]

Charles I died in 1780, at which point Charles William Ferdinand inherited the throne. He soon became known as a model sovereign, a typical enlightened despot of the period, characterized by economy and prudence.[2]

The duke's combination of interest in the well-being of his subjects and habitual caution led to a policy of gradual reforms, a successful middle way between the conservatism of some contemporary monarchs and the over-enthusiastic wholesale changes pursued by others. He sponsored enlightenment arts and sciences; most notably he was patron to the young mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss, paying for him to attend university against the wishes of Gauss' father.[3]

He resembled his uncle Frederick the Great in many ways, but he lacked the resolution of the king, and in civil as in military affairs was prone to excessive caution.[2] He brought Brunswick into close alliance with the king of Prussia, for whom he had fought in the Seven Years' War; he was a Prussian field marshal, and was at pains to make the regiment of which he was colonel a model one.[2]

The duke was frequently engaged in diplomatic and other state affairs. In August 1784 he hosted a secret diplomatic visit from Karl August, Duke of Saxe-Weimar and Saxe-Eisenach (Goethe was a member of Karl August's entourage). The visit was disguised as a family visit, but was in fact to discuss the formation of a league of small- and mid-sized German states as a counterbalance within the Holy Roman Empire to Habsburg Austria's ambitions to trade the Austrian Netherlands for the Electorate of Bavaria. This Fürstenbund (League of Princes) was formally announced in 1785, with the Duke of Brunswick as one of its members and commander of its military forces.[2] The league was successful in forcing the Austrian Joseph II to back down, and thereafter became obsolete.

In 1803 the process of German Mediatisation led to the acquisition of the neighbouring imperial abbeys of Gandersheim and Helmstedt, which were secularised.

Military leader

Invasion of the Netherlands

In 1787 the Duke was made Generalfeldmarschall (field marshal) in the Prussian army. Frederick William II of Prussia appointed him as commander of a 20,000-strong Prussian force which was to invade the United Provinces of the Netherlands (The Dutch Republic). The goal was to suppress the Patriots of the Batavian Revolution, restoring the authority of the stadtholder William V of the House of Orange.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica described the duke's invasion: "His success was rapid, complete and almost bloodless, and in the eyes of contemporaries the campaign appeared as an example of perfect generalship".[2] The Patriots put up no real resistance; their militias were forced to abandon their insurrection, and many Patriots fled to France. The campaign took less than a month: the duke entered the Netherlands on 13 September and the last Patriot city surrendered on 10 October. William V was restored to power, which he was to hold until 1795.

War of the First Coalition

At the outbreak of the War of the First Coalition in the early summer of 1792, Ferdinand was poised with military forces at Coblenz. After the Girondins had arranged for France to declare war on Austria, voted on April 20, 1792, the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II and the Protestant King of Prussia Frederick William II had combined armies and put them under Brunswick's command.

The Brunswick Proclamation

The "Brunswick Proclamation" or "Brunswick Manifesto" that he now issued from Coblenz on July 25, 1792 threatened war and ruin to soldiers and civilians alike, should the Republicans injure Louis XVI and his family. His avowed aim was:

to put an end to the anarchy in the interior of France, to check the attacks upon the throne and the altar, to reestablish the legal power, to restore to the king the security and the liberty of which he is now deprived and to place him in a position to exercise once more the legitimate authority which belongs to him.

Additionally, the manifesto threatened the French population with instant punishment should they resist the Imperial and Prussian armies, or the reinstatement of the monarchy. In large part, the manifesto had been written by Louis XVI's cousin, Louis Joseph de Bourbon, Prince de Condé, who was the leader of a large corps of émigrés in the allied army.

It has been asserted that the manifesto was in fact issued against the advice of Brunswick himself; the duke, a model sovereign in his own principality, sympathized with the constitutional side of the French Revolution, while as a soldier he had no confidence in the success of the enterprise. However, having let the manifesto bear his signature, he had to bear the full responsibility for its consequences.

The proclamation was intended to threaten the French population into submission; it had exactly the opposite effect.

In Paris, Louis XVI was generally believed to be in correspondence with the Austrians and Prussians already, and the republicans became more vocal in the early summer of 1792. It remained for the Duke of Brunswick's proclamation to assure the downfall of the monarchy by his proclamation, which was being rapidly distributed in Paris by July 28 apparently by the monarchists, who badly misjudged the effect it would have (See text in link). The "Brunswick Manifesto" seemed to furnish the agitators with a complete justification for the revolt that they were already planning. The first violent action was carried out on August 10, when the Tuileries Palace was stormed.

Invasion of France

Having already military restored the authority of the House of Orange in 1787, the Duke was less successful against French citizen's army that met him at Valmy. Having secured Longwy and Verdun without serious resistance, he turned back after a mere skirmish in Valmy, and evacuated France. When he counterattacked the Revolutionary French who had invaded Germany, in 1793, he recaptured Mainz after a long siege, but resigned in 1794 in protest at interference by Frederick William II of Prussia.

War of the Fourth Coalition

Prussia did not take part in the Second Coalition or Third Coalition against Revolutionary France. However, in 1806 Prussia declared war on France, beginning the War of the Fourth Coalition. Despite being over 70 years old, the Duke of Brunswick returned to command the Prussian army at the personal request of Louise, Queen of Prussia.[2]

By this stage the Prussian army was regarded as backward, using outdated tactics and with poor intelligence and communication. The structure of the high command has been particularly criticised by historians, with multiple officers developing differing plans and then disagreeing on which should be followed, leading to disorganisation and indecision.

The duke commanded the large Prussian army at Auerstedt during the double Battle of Jena–Auerstedt on 14 October 1806. His forces were defeated by Napoleon's marshal Davout, despite the Prussians outnumbering the French around Auerstedt by two to one. During the battle he was struck by a musket ball and lost both of his eyes; his second-in-command Friedrich Wilhelm Carl von Schmettau was also mortally wounded, causing a breakdown in the Prussian command. Severely wounded, the Duke was carried with his forces before the advancing French. He died of his wounds in Ottensen on 10 November 1806.[2]

Personal life and travels

Shortly after the Seven Years' War ended in 1763, he married Princess Augusta of Great Britain.[1] The couple then embarked on a wide-ranging tour of Europe, visiting many of the major states.

Augusta first took Charles William Ferdinand to visit her native Britain (Augusta was the elder sister of King George III).[1] In 1766 they went to France, where they were received by both his allies and recent battlefield enemies with respect.[2] In Paris he made the acquaintance of Marmontel. The couple next proceeded to Switzerland, where they met Voltaire. The longest stop on their travels was Rome, where they remained for a long time exploring the antiquities of the city under the guidance of Winckelmann. After a visit to Naples they returned to Paris, and thence to Brunswick.[2]

The couple had four sons and three daughters.

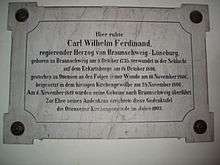

When he died in 1806, the duke's body was provisionally laid to rest in Christianskirche. It was later transferred for reburial in Brunswick Cathedral on 6 November 1819.

Offspring

_and_wife.jpg)

Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand's eldest son and designated heir, Karl Georg August (1766–1806), married Frederika Luise Wilhelmine, Princess of Orange-Nassau, daughter of William V, Prince of Orange and Wilhelmina of Prussia, in 1790. He died childless shortly before his father on 20 September 1806.

His successor, Friedrich Wilhelm (1771 – June 16, 1815), who was one of the bitterest opponents of Napoleonic domination in Germany, took part in the war of 1809 at the head of a corps of partisans, fled to England after the Battle of Wagram, and returned to Brunswick in 1813, where he raised fresh troops. He was killed at the Battle of Quatre Bras.[2]

The remaining two sons, Georg Wilhelm Christian (1769–1811) and August (1770–1822), were declared incapacitated and excluded from the line of succession; neither of them married. The eldest daughter, Auguste Caroline Friederike (1764–1788), married King Frederick I of Württemberg. The second daughter, Caroline (1768–1821), married, with very unhappy results, her first cousin King George IV of the United Kingdom.

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Auguste Caroline Friederike Luise | 3 December 1764 | 27 September 1788 | married 1780, Friedrich III, Duke of Württemberg; had issue |

| Karl Georg August | 8 February 1766 | 20 September 1806 | married 1790, Frederika Luise Wilhelmine, Princess of Orange-Nassau; no issue |

| Caroline Amalie Elisabeth | 17 May 1768 | 7 August 1821 | married 1795, George IV of the United Kingdom; had issue |

| Georg Wilhelm Christian | 27 June 1769 | 16 September 1811 | Declared an invalid; Excluded from line of succession |

| August | 18 August 1770 | 18 December 1822 | Declared an invalid; Excluded from line of succession |

| Friedrich Wilhelm | 9 October 1771 | 16 June 1815 | married 1802, Maria Elisabeth Wilhelmine, Princess of Baden; had issue |

| Amelie Karoline Dorothea Luise | 22 November 1772 | 2 April 1773 |

Ancestry

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Brunswick, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of. |

- Text of the Proclamation of the Duke of Brunswick-Luneburg, 1792

- Prussian Army during the Napoleonic Wars

- Fitzmaurice, Edmond (1901). Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick: An Historical Study, 1735-1806. London: Longmans, Green, & co. Retrieved 29 January 2016.

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 "BRUNSWICK-LÜNEBURG, Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of". Napoleon.org. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Brunswick, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Brunswick, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Dunnington, G. Waldo. (May 1927). The Sesquicentennial of the Birth of Gauss at the Wayback Machine (archived February 26, 2008) Scientific Monthly XXIV: 402–414. Retrieved on 29 June 2005. Now available at "The Sesquicentennial of the Birth of Gauss". Retrieved 28 January 2016.

General sources

- Lord Fitzmaurice, Charles W. F., duke of Brunswick (London, 1901)

- Memoir in Allgemeine deutsche Biographie, vol. ii. (Leipzig, 1882)

- Arthur Chuquet, Les Guerres de la Révolution: La Première Invasion prussienne (Paris)

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

| Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel House of Brunswick-Bevern Cadet branch of the House of Welf Born: 9 October 1735 Died: 10 November 1806 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Charles I |

Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg Prince of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel 1780–1806 |

Succeeded by Frederick William |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|