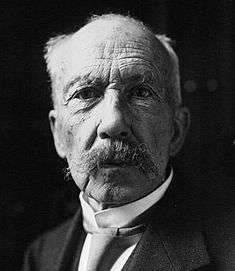

Charles Richet

| Charles Richet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

August 25, 1850 Paris |

| Died |

December 4, 1935 (aged 85) Paris |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (1913) |

Charles Robert Richet (25 August 1850 – 4 December 1935) was a French physiologist who initially investigated a variety of subjects such as neurochemistry, digestion, thermoregulation in homeothermic animals, and breathing. He won the Nobel Prize "in recognition of his work on anaphylaxis" in 1913.[1] He also presided over the French Eugenic Society from 1920 to 1926.

Richet devoted many years to the study of paranormal and spiritualist phenomena, coining the term "ectoplasm".

Life

During his studies, Richet spent a period as an intern at the Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, where he observed Jean-Marie Charcot's work with hysterical patients.

In 1887 Richet was named professor of physiology at the Collège de France, and in 1898 he became a member of the Académie de Médecine. It was, however, his work with Paul Portier on anaphylaxis (his term for a sensitized individual's sometimes lethal reaction to a second, small-dose injection of an antigen) that in 1913 won him the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. This research helped elucidate hay fever, asthma and other allergic reactions to foreign substances and explained some previously not understood cases of intoxication and sudden death. In 1914 he became a member of the Académie des Sciences.

Richet was a man of many interests, and his works included books about history, sociology, philosophy, psychology, as well as theatre plays and poetry. He was a pioneer in aviation.

He also had a deep interest in extrasensory perception and hypnosis. In 1884 Alexandr Aksakov interested him in the medium Eusapia Palladino. In 1891 Richet founded the Annales des sciences psychiques. He kept in touch with renowned occultists and spiritists of his time such as Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, Frederic William Henry Myers and Gabriel Delanne.

Starting in 1902 the French pacifist societies began to meet at a National Peace Congress, which often had several hundred attendees. However, they were unable to unify the pacifist forces apart from setting up a small Permanent Delegation of French Pacifist Societies in 1902, led by Charles Richet, with Lucien Le Foyer as Secretary-General.[2]

In 1905 Richet was named president of the Society for Psychical Research in the United Kingdom, and coined the term "ectoplasm." He experimented with Eva Carrière, Elisabeth D'Espérance, William Eglinton and Stefan Ossowiecki.

In 1919 he became honorary president of the Institut Métapsychique International in Paris, and, in 1929, full-time president.

Parapsychology

As a scientist, Richet was positive about a physical explanation for paranormal phenomena.[3] He wrote: "It has been shown that as regards subjective metapsychics the simplest and most rational explanation is to suppose the existence of a faculty of supernormal cognition ... setting in motion the human intelligence by certain vibrations that do not move the normal senses."[4]

He later wrote about a “sixth sense,” an ability to perceive the hypothetical vibrations; he discussed this hypothesis in his book Our Sixth Sense (1928).[5]

In the early 20th century Joaquin María Argamasilla known as the "Spaniard with X-ray Eyes" claimed to be able to read handwriting or numbers on dice through closed metal boxes. Argamasilla managed to fool Gustav Geley and Richet into believing he had genuine psychic powers.[6] In 1924 he was exposed by Harry Houdini as a fraud. Argamasilla peeked through his simple blindfold and lifted up the edge of the box so he could look inside it without others noticing.[7]

Spiritualism

Richet believed that some mediumship could be explained physically due to the external projection of a material substance (ectoplasm) from the body of the medium, however he denied this substance had anything to do with spirits.[8] Richet rejected the spirit hypothesis of mediumship, instead supporting the sixth sense hypothesis.[9] According to Richet:

| “ | It seems to me prudent not to give credence to the spiritistic hypothesis... it appears to me still (at the present time, at all events) improbable, for it contradicts (at least apparently) the most precise and definite data of physiology, whereas the hypothesis of the sixth sense is a new physiological notion which contradicts nothing that we learn from physiology. Consequently, although in certain rare cases spiritism supplies an apparently simpler explanation, I cannot bring myself to accept it. When we have fathomed the history of these unknown vibrations emanating from reality – past reality, present reality, and even future reality – we shall doubtless have given them an unwonted degree of importance. The history of the Hertzian waves shows us the ubiquity of these vibrations in the external world, imperceptible to our senses.[10] | ” |

Joseph McCabe has written that Richet was duped by the tricks of the fraudulent mediums Eva Carrière and Eusapia Palladino.[11]

Eva Carrière

In 1905, Eva Carrière held a series of séances at Villa Carmen and sitters were invited. In these séances she claimed to materialize a spirit called Bien Boa a 300-year-old Brahmin Hindu, however, photographs taken of Boa looked like the figure was made from a large cardboard cutout.[12] In other sittings Richet reported that Boa was breathing, had moved around the room and had touched him, a photograph taken revealed Boa to be a man dressed up in a cloak, helmet and beard.[13]

A newspaper article in 1906 had revealed that an Arab coachman known as Areski who had previously worked at the villa had been hired to play the part of Bien Boa and that the entire thing was a hoax. Areski wrote that he made his appearance into the room by a trapdoor. Carrière had also admitted to being involved with the hoax.[14]

Eusapia Palladino

Richet with Oliver Lodge, Frederic William Henry Myers and Julian Ochorowicz investigated the medium Eusapia Palladino in the summer of 1894 at his house in the Ile Roubaud in the Mediterranean. Richet claimed furniture moved during the séance and that some of the phenomena was the result of a supernatural agency.[15] However, Richard Hodgson claimed there was inadequate control during the séances and the precautions described did not rule out trickery. Hodgson wrote all the phenomena "described could be account for on the assumption that Eusapia could get a hand or foot free." Lodge, Myers and Richet disagreed, but Hodgson was later proven correct in the Cambridge sittings as Palladino was observed to have used tricks exactly the way he had described them.[15]

In July 1895, Eusapia Palladino was invited to England to Myers' house in Cambridge for a series of investigations into her mediumship. According to reports by the investigators Myers and Oliver Lodge, all the phenomena observed in the Cambridge sittings were the result of trickery. Her fraud was so clever, according to Myers, that it "must have needed long practice to bring it to its present level of skill."[16]

In the Cambridge sittings the results proved disastrous for her mediumship. During the séances Palladino was caught cheating in order to free herself from the physical controls of the experiments.[15] Palladino was found liberating her hands by placing the hand of the controller on her left on top of the hand of the controller on her right. Instead of maintaining any contact with her, the observers on either side were found to be holding each other's hands and this made it possible for her to perform tricks.[17] Richard Hodgson had observed Palladino free a hand to move objects and use her feet to kick pieces of furniture in the room. Because of the discovery of fraud, the British SPR investigators such as Henry Sidgwick and Frank Podmore considered Palladino's mediumship to be permanently discredited and because of her fraud she was banned from any further experiments with the SPR in Britain.[17]

In the British Medical Journal on 9 November 1895 an article was published titled Exit Eusapia!. The article questioned the scientific legitimacy of the SPR for investigating Palladino a medium who had a reputation of being a fraud and imposture.[18] Part of the article read "It would be comic if it were not deplorable to picture this sorry Egeria surrounded by men like Professor Sidgwick, Professor Lodge, Mr. F. H. Myers, Dr. Schiaparelli, and Professor Richet, solemnly receiving her pinches and kicks, her finger skiddings, her sleight of hand with various articles of furniture as phenomena calling for serious study."[18] This caused Henry Sidgwick to respond in a published letter to the British Medical Journal, 16 November 1895. According to Sidgwick SPR members had exposed the fraud of Palladino at the Cambridge sittings, Sidgwick wrote "Throughout this period we have continually combated and exposed the frauds of professional mediums, and have never yet published in our Proceedings, any report in favour of the performances of any of them."[19] The response from the Journal questioned why the SPR wastes time investigating phenomena that are the "result of jugglery and imposture" and not urgently concerning the welfare of mankind.[19]

In 1898, Myers was invited to a series of séances in Paris with Richet. In contrast to the previous séances in which he had observed fraud he claimed to have observed convincing phenomena.[20] Sidgwick reminded Myers of Palladino's trickery in the previous investigations as "overwhelming" but Myers did not change his position. This enraged Richard Hodgson, then editor of SPR publications to ban Myers from publishing anything on his recent sittings with Palladino in the SPR journal. Hodgson was convinced Palladino was a fraud and supported Sidgwick in the "attempt to put that vulgar cheat Eusapia beyond the pale."[20] It wasn't until the 1908 sittings in Naples that the SPR reopened the Palladino file.[21]

Fraud

In 1954, the Society for Psychical Research member Rudolf Lambert published a report revealing details about a case of fraud that was covered up by many early members of the Institute Metapsychique International (IMI).[22] Lambert who had studied Gustav Geley's files on the medium Eva Carrière discovered photographs depicting fraudulent ectoplasm taken by her companion Juliette Bisson.[23] Various "materializations" were artificially attached to Eva's hair by wires. The discovery was never published by Geley. Eugene Osty (the director of the institute) and members Jean Meyer, Albert von Schrenck-Notzing and Richet all knew about the fraudulent photographs but were firm believers in mediumship phenomena so demanded the scandal be kept secret.[23]

Works

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Charles Robert Richet |

Richet's works on parascientific subjects, which dominated his later years, include Traité de Métapsychique (Treatise on Metapsychics, 1922), Notre Sixième Sens (Our Sixth Sense, 1928), L'Avenir et la Prémonition (The Future and Premonition, 1931) and La grande espérance (The Great Hope, 1933).

- Richet, C. Traité de métapsychique (Paris, F. Alcan, 1922).

- Maxwell, J & Richet, C. Metapsychical phenomena: methods and observations (London : Duckworth, 1905).

See also

References

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1913 Charles Richet". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ Guieu, Jean-Michel (2005). "6 - Tensions nationalistes et efforts pacifistes". La France, l’Allemagne et l’Europe (1871-1945) (in French). Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- ↑ Alvarado, C. S. (2006). "Human radiations: Concepts of force in mesmerism, spiritualism and psychical research" (PDF). Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 70: 138–162.

- ↑ Richet, C. (1923). Thirty Years of Psychical Research. Translated from the second French edition. New York: Macmillan.

- ↑ Richet, C. (nd, ca 1928). Our Sixth Sense. London: Rider. (First published in French, 1928)

- ↑ Massimo Polidoro. (2001). Final Séance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. pp. 171–172. ISBN 978-1591020868

- ↑ Joe Nickell. (2007). Adventures in Paranormal Investigation. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 215. ISBN 978-0813124674

- ↑ Richet, C. (1923). Thirty Years of Psychical Research. New York: Macmillan. (Translated from the second French edition)

- ↑ Ashby, Robert H. (1972). The Guidebook for the Study of Psychical Research. Rider.

- ↑ Various Reflections on the the [sic] Sixth Sense by Charles Richet

- ↑ McCabe, Joseph. (1920). Scientific Men and Spiritualism: A Skeptic's Analysis. The Living Age. 12 June. pp. 652–657.

- ↑ Buckland, Raymond. (2005). The Spirit Book: The Encyclopedia of Clairvoyance, Channeling, and Spirit Communication. Visible Ink Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-1578592135

- ↑ Brower, M. Brady (2010). Unruly Spirits: The Science of Psychic Phenomena in Modern France. University of Illinois Press. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-0252077517

- ↑ Aykroyd, Peter H.; Narth, Angela and Aykroyd, Dan (2009). A History of Ghosts: The True Story of Séances, Mediums, Ghosts, and Ghostbusters. Rodale Books. p. 59. ISBN 978-1605298757

- 1 2 3 Mann, Walter (1919). The Follies and Frauds of Spiritualism. Rationalist Association. London: Watts & Co. pp. 115–130

- ↑ McCabe, Joseph (1920) Is Spiritualism Based on Fraud?: The Evidence Given by Sir A.C. Doyle and Others. London, Watts & Co. p. 14

- 1 2 Brower, M. Brady (2010). Unruly Spirits: The Science of Psychic Phenomena in Modern France. University of Illinois Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0252077517

- 1 2 "Exit Eusapia!". The British Medical Journal 2 (1819): 1182. 9 November 1895. PMC 2509128.

- 1 2 Sidgwick, Henry (16 November 1895). "Exit Eusapia". The British Medical Journal 2 (1820): 1263–1264. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.1820.1263-e. PMC 2509272.

- 1 2 Oppenheim, Janet (1985). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914. Cambridge University Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-0521265058

- ↑ Polidoro, Massimo. (2003). Secrets of the Psychics: Investigating Paranormal Claims. Prometheus Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-1591020868

- ↑ Lambert, Rudolf (1954). "Dr. Geley's Reports on the Medium Eva C". Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 37: 380–386.

- 1 2 Lachapelle. Sofie (2011). Investigating the Supernatural: From Spiritism and Occultism to Psychical Research and Metapsychics in France, 1853–1931. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-1421400136

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Richet. |

- Works by Charles Richet at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Charles Richet at Internet Archive

- Short biography and bibliography in the Virtual Laboratory of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science

- Richet's Dictionnaire de physiologie (1895–1928) as fullscan from the original

- Charles Robert Richet photo at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009)

- Charles Richet Biography on Nobel Prize website

- Short biography by Nandor Fodor on SurvivalAfterDeath.org.uk with links to several articles on psychical research

|