Charles Booth (social reformer)

George Frederic Watts, c. 1901

Charles James Booth (30 March 1840 – 23 November 1916) was an English social researcher and reformer. He is most famed for his innovative work on documenting working class life in London at the end of the 19th century, work that along with that of Benjamin Seebohm Rowntree influenced government intervention against poverty in the early 20th century and contributed to the creation of Old Age pensions[1] and free school meals for the poorest children.

Booth's wife, Mary Macaulay, was a cousin of the Fabian socialist and author Martha Beatrice Webb, Baroness Passfield (née Potter; 1858–1943). Booth worked closely with Potter for his research on poverty.

St Paul's Cathedral is the grateful recipient of his gift of Holman Hunt's painting: The Light of The World.[2]

Early life

Charles Booth was born in Liverpool, Lancashire on 30 March 1840 to Charles Booth and Emily Fletcher. His father, a scion of the ancient Cheshire family, was a wealthy shipowner and corn merchant as well as being a prominent Unitarian.[3]

He attended the Royal Institution School in Liverpool before being apprenticed in the family business at the age of sixteen.[1]

Booth's father died in 1860, leaving him in control of the family company to which he added a successful glove manufacturing business.[3] Booth entered the skins and leather business with his elder brother Alfred, and they set up Alfred Booth and Company with offices in Liverpool and New York City using a £20,000 inheritance.[4]

After learning shipping trades, Booth was able to persuade Alfred and his sister Emily to invest in steamships and established a service to Pará, Maranhão and Ceará in Brazil. Booth himself went on the first voyage to Brazil on 14 February 1866. He was also involved in the building of a harbour at Manaus which overcame seasonal fluctuations in water levels. Booth described this as his "monument" (to shipping) when he visited Manaus for the last time in 1912.[5]

Booth also had some involvement in politics, although he canvassed unsuccessfully as the Liberal parliamentary candidate in the General Election of 1865. Following the Conservative Party victory in municipal elections in 1866, his interest in active politics waned. This result changed Booth's attitudes, and he foresaw that he could influence people more by educating the electorate, rather than by being a representative in Parliament.[1]

He rejected subsequent offers from Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone of elevation to the House of Lords as a Peer. Booth engaged in Joseph Chamberlain's Birmingham Education League, a survey which looked into levels of work and education in Liverpool. The survey found that 25,000 children in Liverpool were neither in school or work.

On 29 April 1871, Booth married Mary Macaulay, who was niece of the celebrated historian Thomas Babington Macaulay.[1] His eldest daughter married the Hon Sir Malcolm Macnaghten, and others married into the Ritchie and Gore Browne families.

Public health

Booth was critical of the existing statistical data on poverty, by analysing census returns he argued that they were unsatisfactory and later sat on a committee in 1891 which suggested improvements which could be made to them.

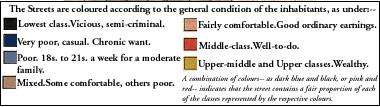

Booth publicly criticised the claims of the leader of the Social Democratic Federation H. M. Hyndman – leader of Britain's first socialist party. In the Pall Mall Gazette of 1885, Hyndman stated that 25% of Londoners lived in abject poverty.[6] Booth investigated poverty in London, working with a team of investigators which included his cousin Beatrice Potter (Beatrice Webb) and the chapter on women's work was conducted by the budding economist Clara Collet. This research, which looked at incidences of pauperism in the East End of London, showed that 35% were living in abject poverty – even higher than the original figure. This work was published under the title Life and Labour of the People in 1889. A second volume, entitled Labour and Life of the People, covering the rest of London, appeared in 1891.[7] Booth also popularised the idea of a 'poverty line', a concept originally conceived by the London School Board.[8] Booth set this line at 10 to 20 shillings, which he considered to be the minimum amount necessary for a family of 4 or 5 people to subsist.[9]

After the first two volumes were published Booth expanded his research. This investigation was carried out by Booth himself and his team of researchers. Nonetheless Booth continued to operate his successful shipping business while these investigations were taking place. The fruit of this research was a second expanded edition of his original work, published as Life and Labour of the People in London in nine volumes between 1892 and 1897. A third edition (now expanded to seventeen volumes) appeared 1902-3.[10]

He used this work to argue for the introduction of Old Age Pensions which he described as "limited socialism". Booth argued that such reforms would help prevent socialist revolution from occurring in Britain. Booth was far from tempted by the ideals of socialism, but had sympathy with the working classes and, as part of his investigations, he took lodgings with working-class families and recorded his thoughts and findings in his diaries.

The London School of Economics keeps his work on an online searchable database.[11] BMJ Open has based some areas of its research on his work.

Political views

While Booth's attitudes towards poverty might make him seem fairly left-wing, Booth actually became more conservative in his views in later life. Some of his investigators such as Beatrice Potter became Socialists as a result of this research, however Booth was critical of the way in which the Liberal Government appeared to support Trade Unions after they won the 1906 General Election.

Influence of his work

Life and Labour of the People in London can be seen as one of the founding texts of British sociology, drawing on both quantitative (statistical) methods and qualitative methods (particularly ethnography). Because of this, it was an influence on Chicago School sociology (notably the work of Robert E. Park) and later the discipline of community studies associated with the Institute of Community Studies in East London.

The importance of Booth's work in social statistics was recognised by the Royal Statistical Society, which bestowed upon him the first Guy Medal in Gold in 1882, and he was elected as President of that society in the same year. Booth was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1899 "as having applied Scientific Methods to Social Investigation".[12]

Thringstone

In later life, Booth moved to Grace Dieu Manor near Thringstone, Leicestershire. Here he built England's first community centre, and founded Grace Dieu Cricket Club.[13] Booth was buried in the churchyard of Saint Andrew's Church[14] in the village, and a memorial dedicated to him stands on the village green. There is also a blue plaque on the house where he lived in South Kensington, 6 Grenville Place.[15]

Works

- Life and Labour of the People, 1st ed., Vol. I. (1889).

- Labour and Life of the People, 1st ed., Vol II. (1891).

- Life and Labour of the People in London, 2nd ed., (1892–97). 9 vols.

- Life and Labour of the People in London, 3rd ed., (1902–03). 17 vols.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Charles Booth (1840–1916) – a biography (Charles Booth Online Archive)

- ↑ www.stpauls.co.uk

- 1 2 Unitarian Society

- ↑ Charles Booth (1840–1916) – a biography (Charles Booth Online Archive)

- ↑ Norman-Butler, Belinda (1972). Victorian Aspirations. London: Allen & Unwin. p. 177. ISBN 0-04-923059-X.

- ↑ Charles Booth's London (1969) edited by Albert Fried and Richard Ellman. London, Hutchinson: xxviii

- ↑ The reversal of the words in the title of the second volume was due to the original title "Life and Labour" being claimed by Samuel Smiles who wrote a similarly titled book in 1887.

- ↑ Gillie, Alan (1996). "The Origin of the Poverty Line". The Economic History Review 49 (4): 715–730 [p. 726]. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1996.tb00589.x.

- ↑ David Boyle – The Tyranny of Numbers p.116

- ↑ Charles Booth's London (1969) edited by Albert Fried and Richard Ellman. London, Hutchinson: 341

- ↑ Booth Poverty Map & Modern map (Charles Booth Online Archive)

- ↑ Royal Society citation

- ↑ gdpcc.hitscricket.com

- ↑ http://www.thringstonestandrews.co.uk

- ↑ "Charles Booth blue plaque". openplaques.org. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Booth. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Booth, Charles. |

- The Charles Booth Online Archive

- Works by or about Charles Booth at Internet Archive

- www.burkespeerage.com

- Charles Booth Papers at Senate House Library, University of London

- Spartacus description of Booth's life

- The centre for Spatially Integrated Social Science

- Charles Booth (1840–1916) – a biography

- Middlesex Universities' Business School

- Ben Gidley, The Proletarian Other: Charles Booth and the Politics of Representation (London: Centre for Urban and Community Research, Goldsmiths College, 2000).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|