Chaldea

Chaldea (/kælˈdiːə/), from Ancient Greek: Χαλδαία, Chaldaia; Akkadian: māt Kaldu/Kašdu; Hebrew: כשדים, Kaśdim;[1] Aramaic: ܟܠܕܘ, Kaldo, also spelled Chaldaea, was a small Semitic nation that emerged between the late 10th and early 9th century BC, surviving until the mid 6th century BC, after which it disappeared as the Chaldean tribes were absorbed into the native population of Babylonia.[2] It was located in the marshy land of the far southeastern corner of Mesopotamia, and briefly came to rule Babylon.

During a period of weakness in the East Semitic speaking empire of Babylonia, new tribes of West Semitic-speaking migrants[3] arrived in the region from the Levant between the 11th and 10th centuries BC. The earliest waves consisted of Suteans and Arameans, followed a century or so later by the Kaldu, a group who became known later as the Chaldeans or the Chaldees. The Hebrew Bible uses the term כשדים (Kaśdim) and this is translated as Chaldaeans in the Septuagint, although there is some dispute as to whether Kasdim in fact means Chaldean. These migrations did not affect Assyria to the north, which repelled these incursions.

The short-lived 11th dynasty of the Kings of Babylon (6th century BC) is conventionally known to historians as the Chaldean Dynasty, although the last rulers, Nabonidus and his son Belshazzar, were known to be from Assyria.[4]

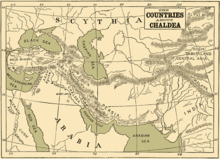

These nomad Chaldeans settled in the far southeastern portion of Babylonia, chiefly on the right bank of the Euphrates. Though for a short time the name later commonly referred to the whole of southern Mesopotamia, this was a misnomer, as Chaldea proper was in fact only the plain in the far southeast formed by the deposits of the Euphrates and the Tigris, extending about four hundred miles along the course of these rivers, and averaging about a hundred miles in width.

Land

Chaldea as a name is used in two different senses. In the early period, between the early 800's and late 600's BC, it was the name of a small sporadically independent territory under the domination of the Neo Assyrian Empire in southeastern Babylonia, extending to the western shores of the Persian Gulf.[1] At some point after the Chaldean tribes settled in the region it eventually became called mat Kaldi "land of Chaldeans" by the native Mesopotamian Assyrians and Babylonians. The expression mat Bit Yakin is also used, apparently synonymously. Bit Yakin was likely the chief or capital city of the land. The king of Chaldea was also called the king of Bit Yakin, just as the kings of Babylonia and Assyria were regularly styled simply king of Babylon or Assur, the capital city in each case. In the same way, the Persian Gulf was sometimes called "the Sea of Bit Yakin", and sometimes "the Sea of the Land of Chaldea".

The boundaries of the early lands settled by Chaldeans in the early 800's BC have not been identified with precision by historians. Chaldea generally referred to the low, marshy, alluvial land around the estuaries of the Tigris and Euphrates, which in ancient times discharged their waters through separate mouths into the sea. In a later time, between 608 BC and 557 BC, when the Chaldean tribe had burst their narrow bonds and obtained their short lived period of ascendency over all of Babylonia, they briefly gave their name to the whole land, which was then called Chaldea by some peoples, particularly the Jews, although this term eventually fell out of use.

From the 10th to late 7th centuries BC, Chaldea, like the rest of Mesopotamia and much of the ancient Near East and Asia Minor, came to be dominated by the Neo Assyrian Empire (911–608 BC), which was based in northern Mesopotamia.

The Old Testament book of the prophet Habbakuk describes the Chaldeans as "a bitter and swift nation".[5]

Chaldean people

Unlike the East Semitic Akkadian-speaking Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians, whose ancestors had been established in Mesopotamia since the 30th century BC, the Chaldeans were not a native Mesopotamian people, but were late 10th or early 9th century BC West Semitic Levantine migrants to the south eastern corner of the region, who had played no part in the previous 3,000 years of Mesopotamian civilization and history.[6][7] They are also not to be confused with the unrelated modern Chaldean Catholics of northern Iraq, who are accepted to be one and the same people as the modern Assyrians.[8][9][10] The ancient Chaldeans seem to have appeared sometime between c. 940–860 BC, a century or so after other new Semitic arrivals, the Arameans and the Suteans, appeared in Babylonia, c. 1100 BC. This was a period of weakness in Babylonia, and its ineffectual native kings were unable to prevent new waves of semi-nomadic foreign peoples from invading and settling in the land.[11]

Though belonging to the same West Semitic ethnic group and migrating from the same Levantine regions as the earlier arriving Arameans, they are to be differentiated; the Assyrian king Sennacherib, for example, carefully distinguishes them in his inscriptions.

The Chaldeans were rapidly and completely assimilated into the dominant Assyro-Babylonian culture, as was the case for the Amorites, Kassites, Suteans and Arameans before them. By the time Babylon fell in 539 BC, the Chaldean tribes had already disappeared as a distinct race, becoming completely absorbed into the general population of southern Mesopotamia, and the term "Chaldean" was no longer used or relevant in describing a specific ethnicity. However, the term lingered, but was used only in relation to a socio-economic class of astrologers, and not a race of people. The nation of Chaldea in southeast Mesopotamia seems to have disappeared even before the fall of Babylon, and the succeeding Achaemenid Empire did not retain a province or land called Chaldea, and made no mention of a Chaldean race in its annals.

The Chaldeans originally spoke a West Semitic language similar to Aramaic. However, they eventually adopted the Babylonian dialect of Akkadian, the same East Semitic language save for slight peculiarities in sound and characters, as Assyrian Akkadian. During the Assyrian Empire, the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III introduced an Eastern Aramaic dialect as the lingua franca of his empire. In late periods, both the Babylonian and Assyrian dialects of Akkadian ceased to be spoken, and Mesopotamian Aramaic took its place across Mesopotamia, including among the Chaldeans. The language remains the mother tongue of the Assyrian (also known as Chaldo-Assyrian) Christians of northern Iraq and its surrounds to this day. One form of this widespread language is used in Daniel and Ezra, but the use of the name "Chaldee" to describe it, first introduced by Jerome, is a misnomer.

In the Hebrew Bible, the prophet Abraham is stated to have originally come from "Ur of the Chaldees" (Ur Kaśdim). If this city is identified with the ancient Sumerian city state of Ur, it would be within what would many centuries later become the Chaldean homeland south of the Euphrates. However, it must be pointed out that no extra-Biblical evidence has yet been discovered indicating that the Chaldeans existed in Mesopotamia (or anywhere else in historical record) at the time Abraham (circa 1800–1700 BC) is believed to have existed, arriving some eight or nine hundred years later.[12] The traditional identification with a site in Assyria (a nation in Upper Mesopotamia predating Chaldea by well over thirteen hundred years, and never recorded in historical annals as ever having been inhabited by the much later arriving Chaldeans) would then imply the much later sense of "Babylonia". Some interpreters have additionally identified Abraham's birthplace with Chaldia in Asia Minor on the Black Sea, a distinct region utterly unrelated geographically, culturally and ethnically to the southeast Mesopotamian Chaldea. According to the Book of Jubilees, Ur Kaśdim (and Chaldea) took their names from Ura and Kesed, descendants of Arpachshad. However, by the beginning of the 21st century, and despite sporadic attempts by more conservative theologically minded scholars such as Kenneth Kitchen to interpret these Biblical patriarchal narratives as actual true history, many modern archaeologists, orientalists and historians had "given up hope of recovering any context that would make Abraham, Isaac or Jacob credible or realistic 'historical figures'"[13]

Modern Chaldean Christians

The term "Chaldean" has fairly recently been revived to describe those Assyrians who broke from the Church of the East in the 16th and 17th centuries AD and entered communion with the Roman Catholic Church. This is a historic, ethnic and geographic inaccuracy. After initially calling it "The Church of Assyria and Mosul" in 1553 AD and designating its first leader as the "Patriarch of the East Assyrians", it was later renamed the Chaldean Catholic Church in 1683 AD. However, this line also reverted back to the Assyrian church, whereas the modern Chaldean Catholic Church was only founded in northern Mesopotamia 1830 AD. The term Chaldean Catholic should thus be understood purely as a Christian denominational rather than a racial, ethnic or historical term, as the modern Chaldean Catholics are in fact ethnically Assyrian people,[14] converts to Catholicism, and long indigenous to the Assyrian homeland in northern Mesopotamia, rather than relating to long extinct Chaldeans who hailed from The Levant and settled in the far southeastern parts Mesopotamia before wholly disappearing during the 6th century BC. There has been no accredited academic study nor historical, archaeological or anthropological evidence that links the modern Chaldean Catholics of northern Iraq to the ancient Chaldeans of south eastern Iraq, in other words no Chaldean continuity. The evidence points to their being one and the same people as, and hailing from the same region as, the Assyrians. In other words, they are in fact a part of the Assyrian continuity.

The naming by Rome is believed to be due to a misinterpretation of the term Ur Kasdim, the supposed north Mesopotamian birthplace of Abraham in Hebraic tradition as Ur of the Chaldees, and a reluctance to use the earlier terms, such as Assyrians, East Assyrians, East Syrians and Nestorians, due to their connotations with the Assyrian Church of the East and Syriac Orthodox Church.[15]

It is noteworthy that the term "Chaldeans" had a history of selective use by Rome,[16] having been previously officially used by the Council of Florence in 1445 AD as a new name for a group of Greek Nestorians of Cyprus who entered in Full Communion with the Catholic Church. Rome then used the term Chaldeans to indicate the members of the Church of the East in Communion with Rome primarily in order to avoid the terms Nestorian, Assyrian and Syriac, which were theologically unacceptable, having connotations to churches doctrinally and politically at odds with The Vatican. This was also done in 1681 AD for Joseph I and later, after his line reverted back to the Assyrian church, in 1830 AD when Yohannan Hormizd, of the line of Alqosh, became the first so called "Patriarch of Babylon of the Chaldeans" of the modern Chaldean Catholic Church. In addition, Rome had also long inaccurately used the name Chaldea to designate the completely unrelated Chaldia in Asia Minor on the Black Sea.

History

The region that the Chaldeans eventually made their homeland was in relatively poor southeastern Mesopotamia, at the head of the Persian Gulf. They appear to have migrated into southern Babylonia from The Levant at some unknown point between the end of the reign of Ninurta-kudurri-usur II (a contemporary of Tiglath-Pileser II) circa 940 BC, and the start of the reign of Marduk-zakir-shumi I in 855 BC, although there is no historical proof of their existence prior to the late 850s BC.[17]

For perhaps a century or so after settling in the area, these semi-nomadic migrant Chaldean tribes had no impact on the pages of history, seemingly remaining subjugated by the native Akkadian speaking kings of Babylon or by perhaps regionally influential Aramean tribes. The main players in southern Mesopotamia during this period were the indigenous Babylonians and Assyrians, together with the Elamites to the east, and Aramean tribes that had already settled in the region a century or so prior to the arrival of the Chaldeans.

The very first historical attestation of the Chaldeans occurs in 852 BC,[18] in the annals of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III, who mentions invading the southeastern extremes of Babylonia and subjugating one Mushallim-Marduk, the chief of the Amukani tribe and overall leader of the Kaldu tribes,[19] together with capturing the town of Baqani, extracting tribute from Adini, chief of the Bet-Dakkuri, another Chaldean tribe.

Shalmanesser III had invaded Babylonia at the request of its own king, Marduk-zakir-shumi I, the Babylonian king being threatened by his own rebellious relations, together with powerful Aramean tribes. The subjugation of the Chaldean tribes appears to have been an aside, as they were not at that time a powerful force, or a threat to the native Babylonian king.

Important Kaldu regions in southeastern Babylonia were Bit-Yâkin (the original area the Chaldeans settled in on the Persian Gulf), Bet-Dakuri, Bet-Adini, Bet-Amukkani, and Bet-Shilani.

Chaldean leaders had by this time already adopted native Assyro-Babylonian names, religion, language and customs, indicating that they had become Akkadianized to a great degree.

The Chaldeans remained quietly ruled by the native Babylonians (who were in turn subjugated by their Assyrian relations) for the next seventy-two years, only coming to historical prominence in Babylonia in 780 BC, when a previously unknown Chaldean named Marduk-apla-usur usurped the throne from the native Babylonian king Marduk-bel-zeri (790–780 BC). The latter was a vassal of the Assyrian king Shalmaneser IV (783–773 BC), who was otherwise occupied quelling a civil war in Assyria at the time.

This was to set a precedent for all future Chaldean aspirations on Babylon during the Neo Assyrian Empire; always too weak to confront a strong Assyria alone and directly, the Chaldeans awaited periods when Assyrian kings were distracted elsewhere or engaged in internal conflicts, then, in alliance with other powers stronger than themselves (usually Elam), they made a bid for control over Babylonia.

Shalmaneser IV attacked and defeated Marduk-apla-usur, retaking northern Babylonia and forcing on him a border treaty in Assyria's favour. The Assyrians allowed him to remain on the throne, although subject to Assyria. Eriba-Marduk, another Chaldean, succeeded him in 769 BC and his son, Nabu-shuma-ishkun in 761 BC, with both being dominated by the new Assyrian king Ashur-Dan III (772–755 BC). Babylonia appears to have been in a state of chaos during this time, with the north occupied by Assyria, its throne occupied by foreign Chaldeans, and continual civil unrest throughout the land.

Chaldean rule proved short lived. A native Babylonian king named Nabonassar (748–734 BC) defeated and overthrew the Chaldean usurpers in 748 BC, restored indigenous rule, and successfully stabilised Babylonia. The Chaldeans once more faded into obscurity for the next three decades. During this time both the Babylonians and the Chaldean and Aramean migrant groups who had settled in the land once more fell completely under the yoke of the powerful Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727 BC), a ruler who introduced Imperial Aramaic as the lingua franca of his empire. The Assyrian king at first made Nabonassar and his successor native Babylonian kings Nabu-nadin-zeri, Nabu-suma-ukin II and Nabu-mukin-zeri his subjects, but decided ruled Babylonia directly from 729 BC. He was followed by Shalmaneser V (727–722 BC), who also ruled Babylon in person.

When Sargon II (722–705 BC) ascended the throne of the Assyrian Empire in 722 BC after the death of Shalmaneser V, he was forced to launch a major campaign in Persia and Media in Ancient Iran. He defeated and drove out the Scythians and Cimmerians who had attacked Assyria's Persian and Median vassal colonies in the region. At the same time, Egypt began encouraging and supporting rebellion against Assyria in Israel and Canaan.

These events allowed the Chaldeans to once more attempt to assert themselves. While the Assyrian king was otherwise occupied defending his Iranian colonies, Marduk-apla-iddina II (the Biblical Merodach-Baladan) of Bit-Yâkin, allied himself with the powerful Elamite kingdom and the native Babylonians, briefly seizing control of Babylon between 721 and 710 BC. With the Scythians and Cimmerians vanquished and the Egyptians defeated and ejected from southern Canaan, Sargon II was free at last to deal with the Chaldeans, Babylonians and Elamites. He attacked and deposed Marduk-apla-iddina II in 710 BC, also defeating his Elamite allies in the process. After defeat by the Assyrians, Merodach-Baladan fled to his protectors in Elam.

In 703, Merodach-Baladan very briefly regained the throne from a native Akkadian-Babylonian ruler Marduk-zakir-shumi II, who was a puppet of the new Assyrian king, Sennacherib (705–681 BC). He was once more soundly defeated at Kish, and once again fled to Elam where he died in exile after one final failed attempt to raise a revolt against Assyria in 700 BC, this time not in Babylon, but in the Chaldean tribal land of Bit-Yâkin. A native Babylonian king named Bel-ibni (703–701 BC) was placed on the throne as a puppet of Assyria.

The next challenge to Assyrian domination came from the Elamites in 694 BC, with Nergal-ushezib deposing and murdering Ashur-nadin-shumi (700–694 BC), the Assyrian prince who was king of Babylon and son of Sennacherib. The Chaldeans and Babylonians again allied with their more powerful Elamite neighbours in this endeavour. This prompted the Assyrian king Sennacherib to invade and subjugate Elam and Chaldea and to sack Babylon, laying waste to and largely destroying the city. Babylon was regarded as a sacred city by all Mesopotamians, including the Assyrians, and this act eventually resulted to Sennacherib's being murdered by his own sons while he was praying to the god Nisroch in Nineveh.

Esarhaddon (681–669 BC) succeeded Sennacherib as ruler of the Assyrian Empire, completely rebuilt Babylon and brought peace to the region. He conquered Egypt, Nubia and Libya and entrench his mastery over the Persians, Medes, Scythians and Cimmerians. For the next 60 or so years Babylon and Chaldea remained under direct Assyrian control. The Chaldeans remained subjugated and quiet during this period, and the next major revolt in Babylon against the Assyrian empire was fermented not by a Chaldean, Babylonian or Elamite, but by Shamash-shum-ukin, who was an Assyrian king of Babylon, and elder brother of Ashurbanipal, the ruler of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Shamash-shum-ukin (668–648 BC) had become infused with Babylonian nationalism after sixteen years peacefully subject to his brother, and despite being Assyrian himself, declared that the city of Babylon and not Nineveh should be the seat of empire.

In 652 BC, he raised a powerful coalition of peoples resentful of their subjugation to Assyria, against his own brother Ashurbanipal. The alliance included the Babylonians, Persians, Chaldeans, Medes, Elamites, Suteans, Arameans, Israelites, Arabs and Canaanites, together with some disaffected Assyrian elements. After a bitter struggle lasting five years, the Assyrian king triumphed over his rebellious brother in 648 BC, Elam was destroyed, and the Babylonians, Persians, Chaldeans, Arabs and others were savagely punished. An Assyrian governor named Kandalanu was then placed on the throne of Babylon to rule on behalf of Ashurbanipal. The next 22 years were peaceful, and neither the Babylonians nor Chaldeans posed a threat to the dominance of Ashurbanipal.

However, after the death of Ashurbanipal (and Kandalanu) in 627 BC, the Neo Assyrian Empire descended into a series of bitter internal dynastic civil wars which were to be the cause of its downfall.

Ashur-etil-ilani (626–623 BC) ascended to the throne of the empire in 626 BC, but was immediately engulfed in rebellions instigated by rival claimants. He was deposed in 623 BC by an Assyrian general (turtanu) named Sin-shumu-lishir (623–622 BC), who was also declared king of Babylon. Sin-shar-ishkun (622–612 BC), the brother of Ashur-etil-ilani, took the throne of empire from Sin-shumu-lishir in 622 BC, but was then himself faced with unremitting rebellion by his own people against his rule. Continual conflict among the Assyrians led to a myriad of subject peoples, from Cyprus to Persia and The Caucasus to Egypt, quietly reasserting their independence and ceasing to pay tribute to Assyria.

Nabopolassar, a previously obscure and unknown Chaldean chieftain, followed the opportunistic tactics laid down by previous Chaldean leaders to take advantage of the chaos and anarchy gripping Assyria and Babylonia and seized the city of Babylon in 620 BC with the help of its native Babylonian inhabitants.

Sin-shar-ishkun amassed a powerful army and marched into Babylon to regain control of the region. Nabopolassar was saved from likely destruction because yet another massive Assyrian rebellion broke out in Assyria proper, including the capital Nineveh, which forced the Assyrian king to turn back in order to quell the revolt. Nabopolassar took advantage of this situation, seizing the ancient city of Nippur in 619 BC, a mainstay of pro-Assyrianism in Babylonia, and thus Babylonia as a whole.

However, his position was still far from secure, and bitter fighting continued in the Babylonian heartlands from 620 to 615 BC, with Assyrian forces encamped in Babylonia in an attempt to eject Nabopolassar. Nabopolassar attempted a counterattack, marched his army into Assyria proper in 616 BC, and tried to besiege Assur and Arrapha (Kirkuk), but was defeated by Sin-shar-ishkun and chased back into Babylonia. A stalemate seemed to have ensued, with Nabopolassar unable to make any inroads into Assyria despite its greatly weakened state, and Sin-shar-ishkun unable to eject Nabopolassar from Babylonia due to constant fighting and civil war among his own people.

Nabopolassar's position, and the fate of the Assyrian empire, was sealed when he entered into an alliance with another of Assyria's former vassals, the Medes, the now dominant people of what was to become Persia. The Median Cyaxares had also recently taken advantage of the anarchy in the Assyrian Empire to free the Iranian peoples, the Medes, Persians and Parthians, from Assyrian rule, moulding them into a large and powerful Median-dominated force. The Medes, Persians, Parthians, Chaldeans and Babylonians formed an alliance that also included the Scythians and Cimmerians to the north.

While Sin-shar-ishkun was fighting both the rebels in Assyria and the Chaldeans and Babylonians in southern Mesopotamia, Cyaxares (hitherto a vassal of Assyria), made an alliance with the Scythians and Cimmerians and launched a surprise attack on civil-war-bleaguered Assyria in 615 BC, sacking Kalhu (the Biblical Calah/Nimrud) and taking Arrapkha (modern Kirkuk). Nabopolassar, still pinned down in southern Mesopotamia, was not involved in this major breakthrough against Assyria. From this point, the alliance of Medes, Persians, Chaldeans, Babylonians, Scythians and Cimmerians fought in unison against Assyria.

Despite the sore state of Assyria, bitter fighting ensued. Throughout 614 BC the alliance of powers continued to make inroads into Assyria itself, although in 613 BC the Assyrians somehow rallied to score a number of counterattacking victories over the Medes-Persians, Babylonians-Chaldeans and Scythians-Cimmerians. This led to a coalition of forces ranged against it to unite and launch a massive combined attack in 612 BC, finally besieging and sacking Nineveh in late 612 BC, killing Sin-shar-ishkun in the process.

A new Assyrian king, Ashur-uballit II (612–605 BC), took the crown amidst the house-to-house fighting in Nineveh, and refused a request to bow in vassalage to the rulers of the alliance. He managed to fight his way out of Nineveh and reach the northern Assyrian city of Harran, where he founded a new capital. Assyria resisted for another seven years until 605 BC, when the remnants of the Assyrian army and the army of the Egyptians (whose dynasty had also been installed as puppets by the Assyrians) were defeated at Karchemish. Nabopolassar and his Median, Scythian and Cimmerian allies were now in possession of much of the huge Neo Assyrian Empire. The Egyptians had belatedly come to the aid of Assyria, fearing that, without Assyrian protection, they would be the next to succumb to the new powers, having already been raided by the Scythians.

The Chaldean king of Babylon now ruled all of southern Mesopotamia (Assyria in the north was ruled by the Medes, although the capitals of Nineveh and Assur might have came under the rule of Neo-Babylon),[20] and the former Assyrian possessions of Aram (Syria), Phoenicia, Israel, Cyprus, Edom, Philistia, and parts of Arabia, while the Medes took control of the former Assyrian colonies in Iran, Asia Minor and the Caucasus.

Nabopolassar was not able to enjoy his success for long, dying in 604 BC, only one year after the victory at Karchemish. He was succeeded by his son, who took the name Nebuchadnezzar II, after the unrelated 12th century BC native Akkadian-Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar I, indicating the extent to which the migrant Chaldeans had become infused with native Mesopotamian culture.

Nebuchadnezzar II and his allies may well have been forced to deal with remnants of Assyrian resistance based in and around Dur-Katlimmu, as Assyrian imperial records continue to be dated in this region between 604 and 599 BC.[21] In addition, the Egyptians remained in the region, possibly in an attempt to aid their former masters and to carve out an empire of their own.

Nebuchadnezzar II was to prove himself to be the greatest of the Chaldean rulers, rivaling another non-native ruler, the 18th century BC Amorite king Hammurabi, as the greatest king of Babylon. He was a patron of the cities and a spectacular builder, rebuilding all of Babylonia's major cities on a lavish scale. His building activity at Babylon, expanding on the earlier major and impressive rebuilding of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon, helped to turn it into the immense and beautiful city of legend. Babylon covered more than three square miles, surrounded by moats and ringed by a double circuit of walls. The Euphrates flowed through the center of the city, spanned by a beautiful stone bridge. At the center of the city rose the giant ziggurat called Etemenanki, "House of the Frontier Between Heaven and Earth," which lay next to the Temple of Marduk. He is also believed by many historians to have built The Hanging Gardens of Babylon (although others believe these gardens were built much earlier by an Assyrian king in Nineveh) for his wife, a Median princess from the green mountains, so that she would feel at home.

A capable leader, Nebuchadnezzar II conducted successful military campaigns; cities like Tyre, Sidon and Damascus were subjugated. He also conducted numerous campaigns in Asia Minor against the Scythians, Cimmerians, and Lydians. Like their Assyrian relations, the Babylonians had to campaign yearly in order to control their colonies.

In 601 BC, Nebuchadnezzar II was involved in a major but inconclusive battle against the Egyptians. In 599 BC, he invaded Arabia and routed the Arabs at Qedar. In 597 BC, he invaded Judah, captured Jerusalem, and deposed its king Jehoiachin. Egyptian and Babylonian armies fought each other for control of the Near East throughout much of Nebuchadnezzar's reign, and this encouraged king Zedekiah of Judah to revolt. After an eighteen-month siege, Jerusalem was captured in 587 BC, thousands of Jews were deported to Babylon, and Solomon's Temple was razed to the ground.

Nebuchadnezzar successfully fought the Pharaohs Psammetichus II and Apries throughout his reign, and during the reign of Pharaoh Amasis in 568 BC it is rumoured that he may have briefly invaded Egypt itself.

By 572, Nebuchadnezzar was in full control of Babylonia, Chaldea, Aramea (Syria), Phonecia, Israel, Judah, Philistia, Samarra, Jordan, northern Arabia, and parts of Asia Minor. Nebuchadnezzar died of illness in 562 BC after a one-year co-reign with his son, Amel-Marduk, who was deposed in 560 BC after a reign of only two years.

End of the Chaldean dynasty

Neriglissar succeeded Amel-Marduk. It is unclear as to whether he was in fact an ethnic Chaldean or a native Babylonian nobleman, as he was not related by blood to Nabopolassar's descendants, having married into the ruling family. He conducted successful military campaigns against the Hellenic inhabitants of Cilicia, which had threatened Babylonian interests. Neriglissar reigned for only four years and was succeeded by the youthful Labashi-Marduk in 556 BC. Again, it is unclear whether he was a Chaldean or a native Babylonian.

Labashi-Marduk reigned only for a matter of months, being deposed by Nabonidus in late 556 BC. Nabonidus was an Assyrian from Harran, the last capital of Assyria, and proved to be the final native Mesopotamian king of Babylon. He and his son, the regent Belshazzar, were deposed by the Persians under Cyrus II in 539 BC.

When the Babylonian Empire was absorbed into the Persian Achaemenid Empire, the name "Chaldean" lost its meaning in reference a particular ethnicity. The original Chaldean tribe had long ago became Akkadianized, adopting Assyro-Babylonian culture, religion, language and customs, blending into the majority native population, and eventually wholly disappearing as a distinct race of people, as had been the case with other preceding migrant peoples, such as the Amorites, Kassites, Suteans and Arameans of Babylonia.

The Persians considered this Chaldean societal class to be masters of reading and writing, and especially versed in all forms of incantation, sorcery, witchcraft, and the magical arts. They spoke of astrologists and astronomers as Chaldeans, and it is used with this specific meaning in the Book of Daniel (Dan. i. 4, ii. 2 et seq.) and by classical writers, such as Strabo.

The disappearance of the Chaldeans as an ethnicity and Chaldea as a land is evidenced by the fact that the Persian rulers of the Achaemenid Empire (539–330 BC) did not retain a province called "Chaldea", nor did they refer to "Chaldeans" as a race of people in their written annals. This is in contrast to Assyria, and for a time Babylonia also, where the Persians retained the names Assyria and Babylonia as designations for distinct geo-political entities within the Achaemenid Empire. In the case of the Assyrians in particular, Achaemenid records show Assyrians holding important positions within the empire, particularly with regards to military and civil administration.[22]

This absence of Chaldeans from the historical record continues throughout the Seleucid Empire, Parthian Empire, Roman Empire, Sassanid Empire, Byzantine Empire and after the Arab Islamic conquest and Mongol Empire.

By the time of Cicero in the 2nd century BC, "Chaldean" appears to have completely disappeared even as a societal term for Babylonian astronomers and astrologers; Cicero refers to "Babylonian astrologers" rather than Chaldean astrologers.[23] Horace does the same, referring to "Babylonian horoscopes" rather than Chaldean[24] in his famous Carpe Diem ode. Cicero views the Babylonian astrologers as holding obscure knowledge, while Horace thinks that they are wasting their time and would be happier "going with the flow".

The terms Chaldee and Chaldean were henceforth only found only in Hebraic and Biblical sources dating from the 6th and 5th centuries BC, and referring specifically to the period of the Chaldean Dynasty of Babylon.

After an absence from history of 2,236 years, the name was revived in 1683 AD by the Roman Catholic Church in the form of the Chaldean Catholic Church as the new name for the "Church of Assyria and Mosul" (so named in 1553 AD). This was not a church founded and populated not by the long extinct Chaldean tribe of southeastern Mesopotamia, who had disappeared from the pages of history over twenty two centuries previously, but founded in northern Mesopotamia by a breakaway group of ethnic Assyrians long indigenous to Upper Mesopotamia (Assyria) who had hitherto been members of the Assyrian Church of the East before entering communion with Rome.[25][26]

See also

- Babylonia

- Assyria

- Neo Assyrian Empire

- Sealand Dynasty

- Neo-Babylonian Empire

- Median Empire

- Achaemenid Empire

- Sumer

- Elam

- Arameans

- Suteans

- Scythians

- Assyrian people

- Semitic people

- Assyrian Church of the East

- Chaldean Catholic Church

- Chaldean Oracles

- Names of Syriac Christians

- Mesopotamian Marshes

References

- 1 2 "Chaldea". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ↑ George Roux – Ancient Iraq – p 281

- ↑ Nordhoff, Sebastian; Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2013). "West Semitic". Glottolog 2.2. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

- ↑ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq

- ↑ "Douay-Rheims Catholic Bible".

- ↑ F Leo Oppenheim – Ancient Mesopotamia

- ↑ Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq

- ↑ "The End of Christianity in the Middle East?". Foreign Policy. 2010-11-02. Retrieved 2015-06-27.

- ↑ Hitti, Philip Khuri (1957), History of Syria, including Lebanon and Palestine Macmillan; St. Martin's P.: London, New York

- ↑ Unrepresented Nations and People Organization | UNPO, Assyrians the Indigenous People of Iraq [1]

- ↑ F. Leo Oppenheim, Ancient Mesopotamia

- ↑ Moore & Kelle 2011, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Dever 2002, p. 98 and fn.2.

- ↑ From a lecture by J. A. Brinkman: "There is no reason to believe that there would be no racial or cultural continuity in Assyria, since there is no evidence that the population of Assyrians were removed." Quoted in Efram Yildiz's "The Assyrians" Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 13.1, p. 22, ref 24

- ↑ Biblical Archaeology Review May/June 2001: Where Was Abraham's Ur?.

- ↑ Council of Florence, Bull of union with the Chaldeans and the Maronites of Cyprus Session 14, 7 August 1445 [1]

- ↑ Georges Roux – Ancient Iraq p. 298

- ↑ A. K. Grayson (1996). Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC II (858–745 B.C.) (RIMA 3). Toronto University Press. pp. 31, 26–28. iv 6

- ↑ Door fitting from the Balawat Gates, BM 124660.

- ↑ Ran Zadok (1984), Assyrians in Chaldean and Achaemenians Babylonia. Page 2.

- ↑ Assyria 1995: Proceedings of the 10th Anniversary Symposium of the Neo-Assyrian Text Corpus Project / Helsinki, September 7–11, 1995.

- ↑ "Assyrians after Assyria". Nineveh.com. 4 September 1999. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ↑ Cicero, Pro Murena, ch. 21

- ↑ Horace, Odes 1.11

- ↑ George V. Yana (Bebla), "Myth vs. Reality" JAA Studies, Vol. XIV, No. 1, 2000 p. 80

- ↑ Angold, Michael (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81113-2.

Lenorman, Francois. Chaldean Magic: Its Origin and Development. London, England: Samuel Bagster and Sons [1877]

External links

- Zénaïde A. Ragozin, Chaldea – from the earliest times to the rise of Assyria, 1893, from Project Gutenberg

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.