Chain walking

In polymer chemistry, chain walking or chain running is a mechanism that operates during some alkene polymerization reactions. This reaction gives rise to branched and hyperbranched hydrocarbon polymers. This process is also characterized by accurate control of polymer architecture and topology.[1] The positions of branches on the polymers are controlled by the choice of a catalyst. The potential applications of polymers formed by this reaction are diverse, from drug delivery to phase transfer agents, nanomaterials, and catalysis.[2]

Catalysts

Catalysts that promote chain walking were discovered in the 1980-1990s. Nickel(II) and palladium(II) complexes of α-diimine ligands were known to efficiently catalyze polymerization of alkenes. Currently nickel and palladium complexes bearing α-diimine ligands, such as the two examples shown, are the most thoroughly described chain walking catalysts in scientific literature.[3]

Mechanism

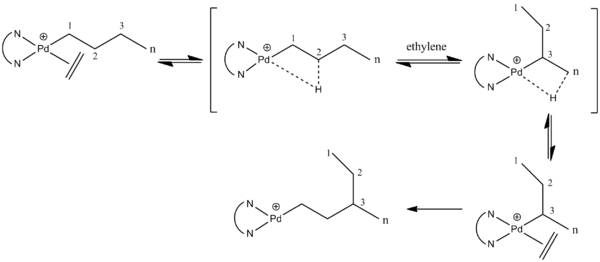

Chain walking occurs after the polymer chain has grown somewhat on the metal catalyst. The precursor is a 16 e− complex with the general formula [Ni(diimine)(C2H4)(chain)]+. The ethylene ligand (the monomer) dissociates to produce a highly unsaturated 14 e− cation. This cation is stabilized by an agostic interaction. β-Hydride elimination then occurs to give a hydride-alkene complex. Subsequent reinsertion of the M-H into the C=C bond, but in the opposite sense gives a metal-alkyl complex.[4] This process moves the metal from the end of a chain to a secondary carbon center. At this stage a molecule of ethylene associates with the palladium complex to give [Pd(diimine)(alkyl)(ethylene)]+. At this second resting state, the ethylene molecule can insert to grow the polymer or dissociate inducing further chain walking. Eventually many branches can form, thereby giving a hyperbranched topology.

References

- ↑ Guan, Z.; Cotts, PM; McCord, EF; McLain, SJ (1999). "Chain Walking: A New Strategy to Control Polymer Topology". Science 283 (5410): 2059–2062. Bibcode:1999Sci...283.2059G. doi:10.1126/science.283.5410.2059. PMID 10092223.

- ↑ Guan, Z. (2010). "Recent Progress of Catalytic Polymerization for Controlling Polymer Topology". Chem. Asian J. 5 (5): 1058–1070. doi:10.1002/asia.200900749. PMID 20391469.

- ↑ Domski, G. J.; Rose, J. M.; Coates, G. W.; Bolig, A. D.; Brookhart, M. (2007). "Living alkene polymerization: New methods for the precision synthesis of polyolefins". Prog. Polym. Sci. 32: 30–92. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.11.001.

- ↑ Atkins, P.; Overton, T.; Rourke, J.; Weller, M.; Armstrong, F.; Hagerman, M. (2010). Inorganic Chemistry (5th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Company. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-19-923617-6.