Cerrejonisuchus

| Cerrejonisuchus Temporal range: Paleocene, 58 Ma | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | Crocodylomorpha |

| Family: | †Dyrosauridae |

| Genus: | †Cerrejonisuchus Hastings et al., 2010 |

| Type species | |

| †Cerrejonisuchus improcerus Hastings et al., 2010 | |

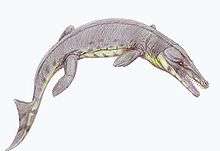

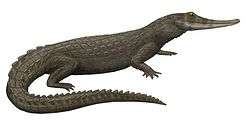

Cerrejonisuchus is an extinct genus of dyrosaurid crocodylomorph. It is known from a complete skull and mandible from the Cerrejón Formation in northeastern Colombia, which is Paleocene in age. Specimens belonging to Cerrejonisuchus and to several other dyrosaurids have been found from the Cerrejón open-pit coal mine in La Guajira. The length of the rostrum is only 54-59% of the total length of the skull, making the snout of Cerrejonisuchus the shortest of all dyrosaurids.[1]

Description

At an estimated length of 1.22 metres (4.0 ft) to 2.22 metres (7.3 ft), Cerrejonisuchus was small for a dyrosaur. This size estimate is based on the dorsal skull lengths of specimens UF/IGM 29 and UF/IGM 31. Cerrejonisuchus has the shortest body length of any known dyrosaur, much smaller than that of the longest dyrosaur, Phosphatosaurus gavialoides, which was 7.22 metres (23.7 ft) to 8.05 metres (26.4 ft) in length.[1]

Currently the only known specimens of Cerrejonisuchus are UF/IGM 29 (the type specimen), UF/IGM 30, UF/IGM 31, and UF/IGM 32. Of these, UF/IGM 29 and UF/IGM 31 are thought to represent fully mature individuals while UF/IGM 32 is thought to represent a less mature individual. In UF/IGM 31, the neurocentral sutures of the anterior dorsal vertebrae are closed, an indication of morphological maturity. Additionally, the presence of well-developed osteoderms is likely to be an indication that the animal was mature because in living crocodylians, the osteoderms begin calcification after 1 year and grow to articulate with other osteoderms to form a dermal shield at maturity. Also, the sutures that separate the bones of the skull in both specimens are fully fused, suggesting that the individuals have reached a late ontogenic stage. In contrast, UF/IGM 32 has an unfused nasal suture, suggesting that it was less mature than the other individuals. UF/IGM 32 is also noticeably smaller than the other specimens.[1]

Relative to the entire skull length, the rostrum of Cerrejonisuchus is the shortest of any dyrosaurid. It, along with Chenanisuchus, are the only short-snouted dyrosaurids. The snout of Cerrejonisuchus is narrow and consistent in width from the external nares, or nostril openings, to the orbits, or eye sockets. The margin of the snout, unlike that of many long-snouted dyrosaurids, is smooth rather than festooned. "Festooned" refers to the lateral undulations in the maxillae and premaxillae that form around the tooth sockets, or alveoli. The external nares are positioned extremely anteriorly at the very tip of the snout. The orbits are oriented anterodorsally, facing upward and slightly forward. The dentition of Cerrejonisuchus is generally homodont, although the third maxillary tooth is enlarged and the fourth is somewhat smaller than the rest. They are conical, labiolingually compressed, each having a relatively rounded apex. The carinae, or tooth edges, are strongly developed both anteriorly and posteriorly. The premaxillary teeth are generally thinner and longer than the maxillary teeth. Like Chenanisuchus, Cerrejonisuchus visibly lacks striations on the tooth surfaces. Unlike many other dyrosaurids, including Dyrosaurus maghribensis, Atlantosuchus coupatezi, Guarinisuchus munizi, Phosphatosaurus gavialoides, and Sokotosuchus ianwilsoni, the teeth of Cerrejonisuchus are not curved.[1]

Classification

A phylogenetic analysis of dyrosaurids by Hastings et al. (2010) placed Cerrejonisuchus relatively basally in the dyrosaur clade between Phosphatosaurus gavialoides and Arambourgisuchus khouribgaensis. Cerrejonisuchus was not found to be closely related to the other short-snouted dyrosaur Chenanisuchus, which was placed at the base of the clade. Although it might be expected that Chenanisuchus and Cerrejonisuchus are closely related because they are the only dyrosaurids with short snouts, the results of the analysis show that snout proportions alone are not indicative of phylogenetic relatedness in dyrosaurs.

Below is the cladogram from Hastings et al. (2010) showing the phylogenetic relationship of Cerrejonisuchus within Dyrosauridae:[1]

| Neosuchia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Paleobiology

Feeding strategy

Cerrejonisuchus likely had a diet consisting of fish, invertebrates, frogs, lizards, small snakes, and possibly mammals.[1][2] The short snout of Cerrejonisuchus is thought to be an adaptation to such a generalized diet. Other long-snouted marine dyrosaurs are presumed to have had a strongly piscivorous diet consisting solely of fish. With its short snout, Cerrejonisuchus would have been able to occupy a new ecological niche in the neotropical rainforest environment of Paleocene Colombia.[2]

Paleoenvironment

Cerrejonisuchus is known from the Middle to Late Paleocene Cerrejón Formation. All known specimens have been found from the Cerrejón open-pit coal mine at the La Puente Pit below Coal Seam 90. The mine has also yielded remains of Titanoboa cerrejonensis, a recently described 12.8 metres (42 ft) long extinct boid that is the largest known snake to have ever existed.[3] Like Cerrejonisuchus, fossils of Titanoboa were found in a gray claystone layer directly underlying Coal Seam 90.[4] Additional dyrosaurid material has been found from the Cerrejón Formation alongside that of Cerrejonisuchus, and is thought to represent at least two different taxa. The age of the Cerrejón Formation has been dated as Middle-Late Paleocene based on carbon isotopes, pollen, spores, and dinoflagellate cysts.[5]

The section of the Cerrejón Formation from which fossils of Cerrejonisuchus have been found was likely deposited in a transitional environment, probably brackish water in a river-to-lagoonal setting. Large freshwater podocnemidid turtles and dipnoan and elopomorph fishes have also been found from this part of the formation.[6] Cerrejonisuchus may have been a food source for Titanoboa, which would have lived in the same brackish water environment.[2] The vertebrate paleofauna of the Cerrejón Formation was similar to modern neotropical riverine vertebrate faunas.[3]

During the Paleocene, river systems would have incised a coastal plain covered by a wet neotropical rainforest. The global temperature was much warmer than it is today, based on paleoclimate models. The latitudinal temperature gradient between the equator and mid-latitudes of South America was similar to the gradient that exists today. Elevated levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are thought to have caused the global greenhouse temperature. The high rainfall estimates and increased pCO2 would have maintained the rainforest floras during the Paleocene greenhouse.[3]

Paleobiogeography

The presence of dyrosaurids such as Cerrejonisuchus in the Paleocene of Colombia suggests that there was a radiation of dyrosaurids in South America following the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (K–T boundary) and the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. There may have been a dispersal from Africa to Brazil, and continued immigration into North America.[7] Colombia can be seen as a transitional route from Brazil to North America, and also to Bolivia, assuming that it was coastal.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hastings, A. K; Bloch, J. I.; Cadena, E. A.; Jaramillo, C. A. (2010). "A new small short-snouted dyrosaurid (Crocodylomorpha, Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Paleocene of northeastern Colombia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 30 (1): 139–162. doi:10.1080/02724630903409204.

- 1 2 3 Kanapaux, B. (February 2, 2010). "UF researchers: Ancient crocodile relative likely food source for Titanoboa". University of Florida News. Retrieved February 3, 2010.

- 1 2 3 Head, J. J.; Bloch, J. I.; Hastings, A. K.; Bourque, J. R.; Cadena, E. A.; Herrera, F. A.; Polly, P. D.; Jaramillo, C. A. (2009). "Giant boid snake from the Palaeocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures" (PDF). Nature 457 (7230): 715–717. doi:10.1038/nature07671. PMID 19194448.

- ↑ Head, J. J.; Bloch, J. I.; Hastings, A. K.; Bourque, J. R.; Cadena, E. A.; Herrera, F. A.; Polly, P. D.; Jaramillo, C. A. (2009). "Supplementary information for "Giant boid snake from the Palaeocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures" (PDF). Nature 457 (7230): 715–717. doi:10.1038/nature07671. PMID 19194448.

- ↑ Jaramillo, C.; Pardo-Trujillo, A.; Rueda, M.; Harrington, G.; Bayona, G.; Torres, V.; Mora, G. (2007). "Palynology of the Upper Paleocene Cerrejón Formation, Northern Colombia". Palynology 31: 153–189. doi:10.2113/gspalynol.31.1.153.

- ↑ Bloch, J.; Cadena, E.; Hastings, A.; Rincon, A.; Jaramillo, C. (2008). "Vertebrate faunas from the Paleocene Bogotá Formation of Northern Colombia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 28 (3, Suppl.): 53A. doi:10.1080/02724634.2008.10010459.

- ↑ Barbosa, J. A.; Kellner, A. W. A.; Viana, M. S. S. (2008). "New dyrosaurid crocodylomorph and evidences for faunal turnover at the K–P transition in Brazil". Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275 (1641): 1385–1391. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.0110. PMC 2602706. PMID 18364311.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||