Centrality

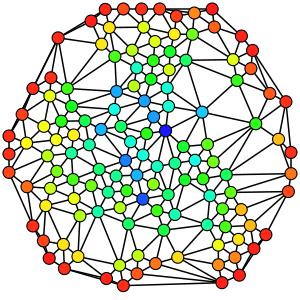

In graph theory and network analysis, indicators of centrality identify the most important vertices within a graph. Applications include identifying the most influential person(s) in a social network, key infrastructure nodes in the Internet or urban networks, and super-spreaders of disease. Centrality concepts were first developed in social network analysis, and many of the terms used to measure centrality reflect their sociological origin.[1] They should not be confused with node influence metrics, which seek to quantify the influence of every node in the network.

Definition and characterization of centrality indices

Centrality indices are answers to the question "What characterizes an important vertex?" The answer is given in terms of a real-valued function on the vertices of a graph, where the values produced are expected to provide a ranking which identifies the most important nodes.[2][3]

The word "importance" has a wide number of meanings, leading to many different definitions of centrality. Two categorization schemes have been proposed. "Importance" can be conceived in relation to a type of flow or transfer across the network. This allows centralities to be classified by the type of flow they consider important.[3] "Importance" can alternately be conceived as involvement in the cohesiveness of the network. This allows centralities to be classified based on how they measure cohesiveness.[4] Both of these approaches divide centralities in distinct categories. A further conclusion is that a centrality which is appropriate for one category will often "get it wrong" when applied to a different category.[3]

When centralities are categorized by their approach to cohesiveness, it becomes apparent that the majority of centralities inhabit one category. The count of the number of walks starting from a given vertex differs only in how walks are defined and counted. Restricting consideration to this group allows for a soft characterization which places centralities on a spectrum from walks of length one (degree centrality) to infinite walks (eigenvalue centrality).[2][5] The observation that many centralities share this familial relationships perhaps explains the high rank correlations between these indices.

Characterization by network flows

A network can be considered a description of the paths along which something flows. This allows a characterization based on the type of flow and the type of path encoded by the centrality. A flow can be based on transfers, where each undivisible item goes from one node to another, like a package delivery which goes from the delivery site to the client's house. A second case is the serial duplication, where this is a replication of the item which goes to the next node, so both the source and the target have it. An example is the propagation of information through gossip, with the information being propagated in a private way and with both the source and the target nodes being informed at the end of the process. The last case is the parallel duplication, with the item being duplicated to several links at the same time, like a radio broadcast which provides the same information to many listeners at once.[3]

Likewise, the type of path can be constrained to: Geodesics (shortest paths), paths (no vertex is visited more than once), trails (vertices can be visited multiple times, no edge is traversed more than once), or walks (vertices and edges can be visited/traversed multiple times).[3]

Characterization by walk structure

An alternate classification can be derived from how the centrality is constructed. This again splits into two classes. Centralities are either Radial or Medial. Radial centralities count walks which start/end from the given vertex. The degree and eigenvalue centralities are examples of radial centralities, counting the number of walks of length one or length infinity. Medial centralities count walks which pass through the given vertex. The canonical example is Freedman's betweenness centrality, the number of shortest paths which pass through the given vertex.[4]

Likewise, the counting can capture either the volume or the length of walks. Volume is the total number of walks of the given type. The three examples from the previous paragraph fall into this category. Length captures the distance from the given vertex to the remaining vertices in the graph. Freedman's closeness centrality, the total geodesic distance from a given vertex to all other vertices, is the best known example.[4] Note that this classification is independent of the type of walk counted (i.e. walk, trail, path, geodesic).

Borgatti and Everett propose that this typology provides insight into how best to compare centrality measures. Centralities placed in the same box in this 2×2 classification are similar enough to make plausible alternatives; one can reasonably compare which is better for a given application. Measures from different boxes, however, are categorically distinct. Any evaluation of relative fitness can only occur within the context of predetermining which category is more applicable, rendering the comparison moot.[4]

Radial-volume centralities exist on a spectrum

The characterization by walk structure shows that almost all centralities in wide use are radial-volume measures. These encode the belief that a vertex's centrality is a function of the centrality of the vertices it is associated with. Centralities distinguish themselves on how association is defined.

Bonacich showed that if association is defined in terms of walks, then a family of centralities can be defined based on the length of walk considered.[2] The degree counts walks of length one, the eigenvalue centrality counts walks of length infinity. Alternate definitions of association are also reasonable. The alpha centrality allows vertices to have an external source of influence. Estrada's subgraph centrality proposes only counting closed paths (triangles, squares, ...).

The heart of such measures is the observation that powers of the graph's adjacency matrix gives the number of walks of length given by that power. Similarly, the matrix exponential is also closely related to the number of walks of a given length. An initial transformation of the adjacency matrix allows differing definition of the type of walk counted. Under either approach, the centrality of a vertex can be expressed as an infinite sum, either

for matrix powers or

for matrix exponentials, where

-

is walk length,

is walk length, -

is the transformed adjacency matrix, and

is the transformed adjacency matrix, and -

is a discount parameter which ensures convergence of the sum.

is a discount parameter which ensures convergence of the sum.

Bonacich's family of measures does not transform the adjacency matrix. The alpha centrality replaces the adjacency matrix with its resolvent. The subgraph centrality replaces the adjacency matrix with its trace. A startling conclusion is that regardless of the initial transformation of the adjacency matrix, all such approaches have common limiting behavior. As  approaches zero, the indices converge to the degree centrality. As

approaches zero, the indices converge to the degree centrality. As  approaches its maximal value, the indices converge to the eigenvalue centrality.[5]

approaches its maximal value, the indices converge to the eigenvalue centrality.[5]

Important limitations

Centrality indices have two important limitations, one obvious and the other subtle. The obvious limitation is that a centrality which is optimal for one application is often sub-optimal for a different application. Indeed, if this were not so, we would not need so many different centralities.

The more subtle limitation is the commonly held fallacy that vertex centrality indicates the relative importance of vertices. Centrality indices are explicitly designed to produce a ranking which allows indication of the most important vertices.[2][3] This they do well, under the limitation just noted. The error is two-fold. Firstly, a ranking only orders vertices by importance, it does not quantify the difference in importance between different levels of the ranking. This may be mitigated by applying Freeman centralization to the centrality measure in question, which provide some insight to the importance of nodes depending on the differences of their centralization scores. Furthermore, Freeman centralization enables one to compare several networks by comparing their highest centralization scores.[6] This approach, however, is seldom seen in practice. Secondly, the features which (correctly) identify the most important vertices in a given network/application do not necessarily generalize to the remaining vertices. For the majority of other network nodes the rankings may be meaningless. This explains why, for example, only the first few results of a Google image search appear in a reasonable order.

While the failure of centrality indices to generalize to the rest of the network may at first seem counter-intuitive, it follows directly from the above definitions. Complex networks have heterogeneous topology. To the extent that the optimal measure depends on the network structure of the most important vertices, a measure which is optimal for such vertices is sub-optimal for the remainder of the network.[7]

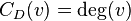

Degree centrality

Historically first and conceptually simplest is degree centrality, which is defined as the number of links incident upon a node (i.e., the number of ties that a node has). The degree can be interpreted in terms of the immediate risk of a node for catching whatever is flowing through the network (such as a virus, or some information). In the case of a directed network (where ties have direction), we usually define two separate measures of degree centrality, namely indegree and outdegree. Accordingly, indegree is a count of the number of ties directed to the node and outdegree is the number of ties that the node directs to others. When ties are associated to some positive aspects such as friendship or collaboration, indegree is often interpreted as a form of popularity, and outdegree as gregariousness.

The degree centrality of a vertex  , for a given graph

, for a given graph  with

with  vertices and

vertices and  edges, is defined as

edges, is defined as

Calculating degree centrality for all the nodes in a graph takes  in a dense adjacency matrix representation of the graph, and for edges takes

in a dense adjacency matrix representation of the graph, and for edges takes  in a sparse matrix representation.

in a sparse matrix representation.

The definition of centrality on the node level can be extended to the whole graph, in which case we are speaking of graph centralization.[8] Let  be the node with highest degree centrality in

be the node with highest degree centrality in  . Let

. Let  be the

be the  node connected graph that maximizes the following quantity (with

node connected graph that maximizes the following quantity (with  being the node with highest degree centrality in

being the node with highest degree centrality in  ):

):

Correspondingly, the degree centralization of the graph  is as follows:

is as follows:

The value of  is maximized when the graph

is maximized when the graph  contains one central node to which all other nodes are connected (a star graph), and in this case

contains one central node to which all other nodes are connected (a star graph), and in this case  .

.

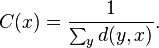

Closeness centrality

In connected graphs there is a natural distance metric between all pairs of nodes, defined by the length of their shortest paths. The farness of a node x is defined as the sum of its distances from all other nodes, and its closeness was defined by Bavelas as the reciprocal of the farness,[9][10] that is:

Thus, the more central a node is the lower its total distance from all other nodes. Note that taking distances from or to all other nodes is irrelevant in undirected graphs, whereas in directed graphs distances to a node are considered a more meaningful measure of centrality, as in general (e.g., in, the web) a node has little control over its incoming links.

When a graph is not strongly connected, a widespread idea is that of using the sum of reciprocal of distances, instead of the reciprocal of the sum of distances, with the convention  :

:

This idea was explicitly stated for undirected graphs under the name harmonic centrality by Rochat (2009),[11] axiomatized by Garg (2009)[12] and proposed once again later by Opsahl (2010).[13] It was studied on general directed graphs by Boldi and Vigna (2014).[14] This idea is also quite similar to market potential proposed in Harris (1954)[15] which now often goes by the term market access.[16]

Note that harmonic centrality is a most natural modification of Bavelas's definition of closeness following the general principle proposed by Marchiori and Latora (2000)[17] that in graphs with infinite distances the harmonic mean behaves better than the arithmetic mean. Indeed, Bavelas's closeness can be described as the denormalized reciprocal of the arithmetic mean of distances, whereas harmonic centrality is the denormalized reciprocal of the harmonic mean of distances.

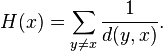

Dangalchev (2006),[18] in a work on network vulnerability proposes for undirected graphs a different definition:

Note that the original definition[18] uses  .

.

The information centrality of Stephenson and Zelen (1989) is another closeness measure, which computes the harmonic mean of the resistance distances towards a vertex x, which is smaller if x has many paths of small resistance connecting it to other vertices.[19]

In the classic definition of the closeness centrality, the spread of information is modeled by the use of shortest paths. This model might not be the most realistic for all types of communication scenarios. Thus, related definitions have been discussed to measure closeness, like the random walk closeness centrality introduced by Noh and Rieger (2004). It measures the speed with which randomly walking messages reach a vertex from elsewhere in the graph—a sort of random-walk version of closeness centrality.[20] Hierarchical closeness of Tran and Kwon (2014)[21] is an extended closeness centrality to deal still in another way with the limitation of closeness in graphs that are not strongly connected. The hierarchical closeness explicitly includes information about the range of other nodes that can be affected by the given node.

Betweenness centrality

Betweenness is a centrality measure of a vertex within a graph (there is also edge betweenness, which is not discussed here). Betweenness centrality quantifies the number of times a node acts as a bridge along the shortest path between two other nodes. It was introduced as a measure for quantifying the control of a human on the communication between other humans in a social network by Linton Freeman[22] In his conception, vertices that have a high probability to occur on a randomly chosen shortest path between two randomly chosen vertices have a high betweenness.

The betweenness of a vertex  in a graph

in a graph  with

with  vertices is computed as follows:

vertices is computed as follows:

- For each pair of vertices (s,t), compute the shortest paths between them.

- For each pair of vertices (s,t), determine the fraction of shortest paths that pass through the vertex in question (here, vertex v).

- Sum this fraction over all pairs of vertices (s,t).

More compactly the betweenness can be represented as:[23]

where  is total number of shortest paths from node

is total number of shortest paths from node  to node

to node  and

and  is the number of those paths that pass through

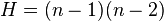

is the number of those paths that pass through  . The betweenness may be normalised by dividing through the number of pairs of vertices not including v, which for directed graphs is

. The betweenness may be normalised by dividing through the number of pairs of vertices not including v, which for directed graphs is  and for undirected graphs is

and for undirected graphs is  . For example, in an undirected star graph, the center vertex (which is contained in every possible shortest path) would have a betweenness of

. For example, in an undirected star graph, the center vertex (which is contained in every possible shortest path) would have a betweenness of  (1, if normalised) while the leaves (which are contained in no shortest paths) would have a betweenness of 0.

(1, if normalised) while the leaves (which are contained in no shortest paths) would have a betweenness of 0.

From a calculation aspect, both betweenness and closeness centralities of all vertices in a graph involve calculating the shortest paths between all pairs of vertices on a graph, which requires  time with the Floyd–Warshall algorithm. However, on sparse graphs, Johnson's algorithm may be more efficient, taking

time with the Floyd–Warshall algorithm. However, on sparse graphs, Johnson's algorithm may be more efficient, taking  time. In the case of unweighted graphs the calculations can be done with Brandes' algorithm[23] which takes

time. In the case of unweighted graphs the calculations can be done with Brandes' algorithm[23] which takes  time. Normally, these algorithms assume that graphs are undirected and connected with the allowance of loops and multiple edges. When specifically dealing with network graphs, often graphs are without loops or multiple edges to maintain simple relationships (where edges represent connections between two people or vertices). In this case, using Brandes' algorithm will divide final centrality scores by 2 to account for each shortest path being counted twice.[23]

time. Normally, these algorithms assume that graphs are undirected and connected with the allowance of loops and multiple edges. When specifically dealing with network graphs, often graphs are without loops or multiple edges to maintain simple relationships (where edges represent connections between two people or vertices). In this case, using Brandes' algorithm will divide final centrality scores by 2 to account for each shortest path being counted twice.[23]

Eigenvector centrality

Eigenvector centrality is a measure of the influence of a node in a network. It assigns relative scores to all nodes in the network based on the concept that connections to high-scoring nodes contribute more to the score of the node in question than equal connections to low-scoring nodes. Google's PageRank is a variant of the eigenvector centrality measure.[24] Another closely related centrality measure is Katz centrality.

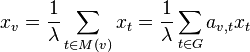

Using the adjacency matrix to find eigenvector centrality

For a given graph  with

with  number of vertices let

number of vertices let  be the adjacency matrix, i.e.

be the adjacency matrix, i.e.  if vertex

if vertex  is linked to vertex

is linked to vertex  , and

, and  otherwise. The centrality score of vertex

otherwise. The centrality score of vertex  can be defined as:

can be defined as:

where  is a set of the neighbors of

is a set of the neighbors of  and

and  is a constant. With a small rearrangement this can be rewritten in vector notation as the eigenvector equation

is a constant. With a small rearrangement this can be rewritten in vector notation as the eigenvector equation

In general, there will be many different eigenvalues  for which an eigenvector solution exists. However, the additional requirement that all the entries in the eigenvector be positive implies (by the Perron–Frobenius theorem) that only the greatest eigenvalue results in the desired centrality measure.[25] The

for which an eigenvector solution exists. However, the additional requirement that all the entries in the eigenvector be positive implies (by the Perron–Frobenius theorem) that only the greatest eigenvalue results in the desired centrality measure.[25] The  component of the related eigenvector then gives the centrality score of the vertex

component of the related eigenvector then gives the centrality score of the vertex  in the network. Power iteration is one of many eigenvalue algorithms that may be used to find this dominant eigenvector.[24] Furthermore, this can be generalized so that the entries in A can be real numbers representing connection strengths, as in a stochastic matrix.

in the network. Power iteration is one of many eigenvalue algorithms that may be used to find this dominant eigenvector.[24] Furthermore, this can be generalized so that the entries in A can be real numbers representing connection strengths, as in a stochastic matrix.

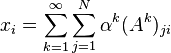

Katz centrality and PageRank

Katz centrality[26] is a generalization of degree centrality. Degree centrality measures the number of direct neighbors, and Katz centrality measures the number of all nodes that can be connected through a path, while the contributions of distant nodes are penalized. Mathematically, it is defined as  where

where  is an attenuation factor in

is an attenuation factor in  .

.

Katz centrality can be viewed as a variant of eigenvector centrality. Another form of Katz centrality is  Compared to the expression of eigenvector centrality,

Compared to the expression of eigenvector centrality,  is replaced by

is replaced by  .

.

It is shown that[27]

the principal eigenvector (associated with the largest eigenvalue of  , the adjacency matrix) is the limit of Katz centrality as

, the adjacency matrix) is the limit of Katz centrality as

approaches

approaches  from below.

from below.

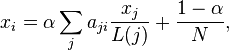

PageRank satisfies the following equation

where

where  is the number of neighbors of node

is the number of neighbors of node  (or number of outbound links in a directed graph). Compared to eigenvector centrality and Katz centrality, one major difference is the scaling factor

(or number of outbound links in a directed graph). Compared to eigenvector centrality and Katz centrality, one major difference is the scaling factor  . Another difference between PageRank and eigenvector centrality is that the PageRank vector is a left hand eigenvector (note the factor

. Another difference between PageRank and eigenvector centrality is that the PageRank vector is a left hand eigenvector (note the factor  has indices reversed).[28]

has indices reversed).[28]

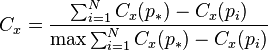

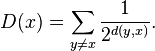

Percolation centrality

A slew of centrality measures exist to determine the ‘importance’ of a single node in a complex network. However, these measures quantify the importance of a node in purely topological terms, and the value of the node does not depend on the ‘state’ of the node in any way. It remains constant regardless of network dynamics. This is true even for the weighted betweenness measures. However, a node may very well be centrally located in terms of betweenness centrality or another centrality measure, but may not be ‘centrally’ located in the context of a network in which there is percolation. Percolation of a ‘contagion’ occurs in complex networks in a number of scenarios. For example, viral or bacterial infection can spread over social networks of people, known as contact networks. The spread of disease can also be considered at a higher level of abstraction, by contemplating a network of towns or population centres, connected by road, rail or air links. Computer viruses can spread over computer networks. Rumours or news about business offers and deals can also spread via social networks of people. In all of these scenarios, a ‘contagion’ spreads over the links of a complex network, altering the ‘states’ of the nodes as it spreads, either recoverably or otherwise. For example, in an epidemiological scenario, individuals go from ‘susceptible’ to ‘infected’ state as the infection spreads. The states the individual nodes can take in the above examples could be binary (such as received/not received a piece of news), discrete (susceptible/infected/recovered), or even continuous (such as the proportion of infected people in a town), as the contagion spreads. The common feature in all these scenarios is that the spread of contagion results in the change of node states in networks. Percolation centrality (PC) was proposed with this in mind, which specifically measures the importance of nodes in terms of aiding the percolation through the network. This measure was proposed by Piraveenan et al.[29]

The Percolation Centrality is defined for a given node, at a given time, as the proportion of ‘percolated paths’ that go through that node. A ‘percolated path’ is a shortest path between a pair of nodes, where the source node is percolated (e.g., infected). The target node can be percolated or non-percolated, or in a partially percolated state.

where  is total number of shortest paths from node

is total number of shortest paths from node  to node

to node  and

and  is the number of those paths that pass through

is the number of those paths that pass through  . The percolation state of the node

. The percolation state of the node  at time

at time  is denoted by

is denoted by  and two special cases are when

and two special cases are when  which indicates a non-percolated state at time

which indicates a non-percolated state at time  whereas when

whereas when  which indicates a fully percolated state at time

which indicates a fully percolated state at time  . The values in between indicate partially percolated states ( e.g., in a network of townships, this would be the percentage of people infected in that town).

. The values in between indicate partially percolated states ( e.g., in a network of townships, this would be the percentage of people infected in that town).

The attached weights to the percolation paths depend on the percolation levels assigned to the source nodes, based on the premise that the higher the percolation level of a source node is, the more important are the paths that originate from that node. Nodes which lie on shortest paths originating from highly percolated nodes are therefore potentially more important to the percolation. The definition of PC may also be extended to include target node weights as well. Percolation centrality calculations run in  time with an efficient implementation adopted from Brandes' fast algorithm and if the calculation needs to consider target nodes weights, the worst case time is

time with an efficient implementation adopted from Brandes' fast algorithm and if the calculation needs to consider target nodes weights, the worst case time is  .

.

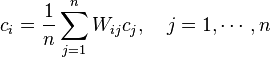

Cross-clique centrality

Cross-clique centrality of a single node, in a complex graph determines the connectivity of a node to different cliques. A node with high cross-clique connectivity facilitates the propagation of information or disease in a graph. Cliques are subgraphs in which every node is connected to every other node in the clique. The cross-clique connectivity of a node  for a given graph

for a given graph  with

with  vertices and

vertices and  edges, is defined as

edges, is defined as  where

where  is the number of cliques to which vertex

is the number of cliques to which vertex  belongs. This measure was used in [30] but was first proposed by Everett and Borgatti in 1998 where they called it clique-overlap centrality.

belongs. This measure was used in [30] but was first proposed by Everett and Borgatti in 1998 where they called it clique-overlap centrality.

Freeman Centralization

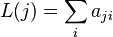

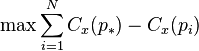

The centralization of any network is a measure of how central its most central node is in relation to how central all the other nodes are.[6] Centralization measures then (a) calculate the sum in differences in centrality between the most central node in a network and all other nodes; and (b) divide this quantity by the theoretically largest such sum of differences in any network of the same size.[6] Thus, every centrality measure can have its own centralization measure. Defined formally, if  is any centrality measure of point

is any centrality measure of point  , if

, if  is the largest such measure in the network, and if

is the largest such measure in the network, and if  is the largest sum of differences in point centrality

is the largest sum of differences in point centrality  for any graph with the same number of nodes, then the centralization of the network is:[6]

for any graph with the same number of nodes, then the centralization of the network is:[6]

Dissimilarity based centrality measures

In order to obtain better results in the ranking of the nodes of a given network, in [31] are used dissimilarity measures (specific to theory of classification and data mining) to enrich the centrality measures in complex networks. This is illustrated with the Eigenvector centrality, calculating the centrality of each node through the solution of the eigenvalue problem

where  (coordinate-to-coordinate product) and

(coordinate-to-coordinate product) and  is an arbitrary dissimilarity matrix, defined through a disimilariry measure, e.g., Jaccard disimilarity given by

is an arbitrary dissimilarity matrix, defined through a disimilariry measure, e.g., Jaccard disimilarity given by

Where this measure permit us quantify the topological contribution (which is why is called contribution centrality) of each node to the centrality of a given node, having more weight/relevance those nodes with greater dissimilarity, since these allow to the given node access to nodes that which themselves can not access directly.

Is noteworthy that  is non-negative because

is non-negative because  and

and  are non-negative matrices, so we can use the Perron–Frobenius theorem to ensure that the above problem has a unique solution for λ = λmax with c non-negative, allowing us to infer the centrality of each node in the network. Therefore, the centrality of the i-th node is

are non-negative matrices, so we can use the Perron–Frobenius theorem to ensure that the above problem has a unique solution for λ = λmax with c non-negative, allowing us to infer the centrality of each node in the network. Therefore, the centrality of the i-th node is

where  is the number of the nodes in the network. Several dissimilarity measures and networks where tested in [32] obtaining improved results in the studied cases.

is the number of the nodes in the network. Several dissimilarity measures and networks where tested in [32] obtaining improved results in the studied cases.

Extensions

Empirical and theoretical research have extended the concept of centrality in the context of static networks to dynamic centrality[33] in the context of time-dependent and temporal networks.[34][35][36]

For generalizations to weighted networks, see Opsahl et al. (2010).[37]

The concept of centrality was extended to a group level as well. For example, group betweenness centrality shows the proportion of geodesics connecting pairs of non-group members that pass through the group.[38][39]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Newman, M.E.J. 2010. Networks: An Introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Bonacich, Phillip (1987). "Power and Centrality: A Family of Measures". American Journal of Sociology (University of Chicago Press) 92: 1170–1182. doi:10.1086/228631.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Borgatti, Stephen P. (2005). "Centrality and Network Flow". Social Networks (Elsevier) 27: 55–71. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2004.11.008.

- 1 2 3 4 Borgatti, Stephen P.; Everett, Martin G. (2006). "A Graph-Theoretic Perspective on Centrality". Social Networks (Elsevier) 28: 466–484. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2005.11.005.

- 1 2 Benzi, Michele; Klymko, Christine (2013). "A matrix analysis of different centrality measures". arXiv:1312.6722.

- 1 2 3 4 Freeman, Linton C. (1979), "centrality in social networks: Conceptual clarification" (PDF), Social Networks 1 (3): 215–239, doi:10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7

- ↑ Lawyer, Glenn (2015). "Understanding the spreading power of all nodes in a network: a continuous-time perspective". Sci Rep 5: 8665. doi:10.1038/srep08665.

- ↑ Freeman, Linton C. "Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification." Social networks 1.3 (1979): 215–239.

- ↑ Alex Bavelas. Communication patterns in task-oriented groups. J. Acoust. Soc. Am, 22(6):725–730, 1950.

- ↑ Sabidussi, G (1966). "The centrality index of a graph". Psychometrika 31: 581–603. doi:10.1007/bf02289527.

- ↑ Yannick Rochat. Closeness centrality extended to unconnected graphs: The harmonic centrality index (PDF). Applications of Social Network Analysis, ASNA 2009.

- ↑ Manuj Garg, "Axiomatic Foundations of Centrality in Networks", SSRN, doi:10.2139/ssrn.1372441

- ↑ Tore Opsahl. "Closeness centrality in networks with disconnected components".

- ↑ Boldi, Paolo; Vigna, Sebastiano (2014), "Axioms for Centrality", Internet Mathematics 10: 222–262, doi:10.1080/15427951.2013.865686

- ↑ C. D. Harris. The, market as a factor in the localization of industry in the united states. Annals of the association of American geographers, 44(4):315–348, 1954

- ↑ Gutberlet, Theresa. Cheap Coal versus Market Access: The Role of Natural Resources and Demand in Germany's Industrialization. Working Paper. 2014.

- ↑ Marchiori, Massimo; Latora, Vito (2000), "Harmony in the small-world" (PDF), Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 285 (3-4): 539–546, doi:10.1016/s0378-4371(00)00311-3

- 1 2 Ch, Dangalchev (2006). "Residual Closeness in Networks". Phisica A 365: 556.

- ↑ Stephenson, K. A.; Zelen, M. (1989). "Rethinking centrality: Methods and examples". Social Networks 11: 1–37. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(89)90016-6.

- ↑ Noh, J. D.; Rieger, H. (2004). "Random Walks on Complex Networks". Phys. Rev. Lett. 92: 118701. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.92.118701.

- ↑ Tran, T.-D. and Kwon, Y.-K. Hierarchical closeness efficiently predicts disease genes in a directed signaling network, Computational biology and chemistry.

- ↑ Freeman, Linton (1977). "A set of measures of centrality based upon betweenness". Sociometry 40: 35–41. doi:10.2307/3033543.

- 1 2 3 Brandes, Ulrik (2001). "A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality" (PDF). Journal of Mathematical Sociology 25: 163–177. doi:10.1080/0022250x.2001.9990249. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- 1 2 http://www.ams.org/samplings/feature-column/fcarc-pagerank

- ↑ M. E. J. Newman. "The mathematics of networks" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-11-09.

- ↑ Katz, L. 1953. A New Status Index Derived from Sociometric Index. Psychometrika, 39–43.

- ↑ Bonacich, P (1991). "Simultaneous group and individual centralities". Social Networks 13: 155–168. doi:10.1016/0378-8733(91)90018-o.

- ↑ How does Google rank webpages? 20Q: About Networked Life

- ↑ Piraveenan, Mahendra (2013). "Percolation Centrality: Quantifying Graph-Theoretic Impact of Nodes during Percolation in Networks". PLOS ONE 8 (1): e53095. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0053095.

- ↑ Faghani, Mohamamd Reza (2013). "A Study of XSS Worm Propagation and Detection Mechanisms in Online Social Networks". IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics and Security.

- ↑ Alvarez-Socorro, A. J.; Herrera-Almarza, G. C.; González-Díaz, L. A. (2015-11-25). "Eigencentrality based on dissimilarity measures reveals central nodes in complex networks". Scientific Reports 5. doi:10.1038/srep17095. PMC 4658528. PMID 26603652.

- ↑ Alvarez-Socorro, A.J.; Herrera-Almarza; González-Díaz, L. A. "Supplementary Information for Eigencentrality based on dissimilarity measures reveals central nodes in complex networks" (PDF). Nature Publishing Group.

- ↑ Braha, D.; Bar-Yam, Y. (2006). "From Centrality to Temporary Fame: Dynamic Centrality in Complex Networks". Complexity 12: 59–63. doi:10.1002/cplx.20156.

- ↑ Hill, S.A.; Braha, D. (2010). "Dynamic Model of Time-Dependent Complex Networks". Physical Review E 82: 046105. doi:10.1103/physreve.82.046105.

- ↑ Gross, T. and Sayama, H. (Eds.). 2009. Adaptive Networks: Theory, Models and Applications. Springer.

- ↑ Holme, P. and Saramäki, J. 2013. Temporal Networks. Springer.

- ↑ Opsahl, Tore; Agneessens, Filip; Skvoretz, John (2010). "Node centrality in weighted networks: Generalizing degree and shortest paths". Social Networks 32 (3): 245–251. doi:10.1016/j.socnet.2010.03.006.

- ↑ Everett, M. G. and Borgatti, S. P. (2005). Extending centrality. In P. J. Carrington, J. Scott and S. Wasserman (Eds.), Models and methods in social network analysis (pp. 57–76). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Puzis, R., Yagil, D., Elovici, Y., Braha, D. (2009).Collaborative attack on Internet users’ anonymity, Internet Research 19(1)

Further reading

- Koschützki, D.; Lehmann, K. A.; Peeters, L.; Richter, S.; Tenfelde-Podehl, D. and Zlotowski, O. (2005) Centrality Indices. In Brandes, U. and Erlebach, T. (Eds.) Network Analysis: Methodological Foundations, pp. 16–61, LNCS 3418, Springer-Verlag.

External links

- https://networkx.lanl.gov/trac/attachment/ticket/119/page_rank.py

- http://www.faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/C10_Centrality.html

- http://socnetv.sourceforge.net/docs/analysis.html#CC

![H= \sum^{|Y|}_{j=1} [C_D(y*)-C_D(y_j)]](../I/m/a3798f88566f7fa69412de388ffa4b9d.png)

![C_D(G)= \frac{\displaystyle{\sum^{|V|}_{i=1}{[C_D(v*)-C_D(v_i)]}}}{H}](../I/m/755c1a4f0f1f33c8fbb345d7c4187c7d.png)

![PC^t(v)= \frac{1}{N-2}\sum_{s \neq v \neq r}\frac{\sigma_{sr}(v)}{\sigma_{sr}}\frac{{x^t}_s}{{\sum {[{x^t}_i}]}-{x^t}_v}](../I/m/2c5a141857c7e0a873385e613ab57d1b.png)