Central Europe

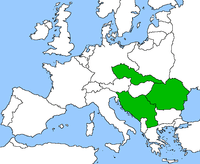

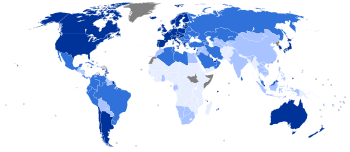

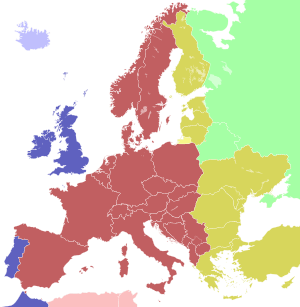

Central Europe lies between Eastern and Western Europe.[1][2][3]

The concept of Central Europe is based on a common historical, social and cultural identity.[4][5][6][7][8][7][9][10][11][12][13]

Central Europe is going through a phase of "strategic awakening",[14] with initiatives like the CEI, Centrope or V4. While the region's economy shows high disparities with regard to income,[15] all Central European countries are listed by the Human Development Index as very highly developed.[16]

Historical perspective

Middle Ages

Elements of unity for Western and Central Europe were Roman Catholicism and Latin. Eastern Europe, which remained Eastern Orthodox Christian, was the area of Byzantine cultural influence; after the schism (1054), it developed cultural unity and resistance to the Western world (Catholic and Protestant) within the framework of Slavonic language and the Cyrillic alphabet.[19][20][21][22]

-

Certain and disputed borders of Great Moravia under Svatopluk I (AD 870–894)

-

Holy Roman Empire in 1600

-

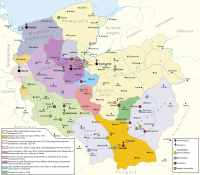

Kingdom of Poland in late 12th-13th centuries.

-

Bohemia in 1273

-

Kingdom of Hungary in 1190

According to Hungarian historian Jenő Szűcs, foundations of Central European history at the first millennium were in close connection with Western European development. He explained that between the 11th and 15th centuries not only Christianization and its cultural consequences were implemented, but well-defined social features emerged in Central Europe based on Western characteristics. The keyword of Western social development after millennium was the spread of liberties and autonomies in Western Europe. These phenomena appeared in the middle of the 13th century in Central European countries. There were self-governments of towns, counties and parliaments.[23]

In 1335 under the rule of the King Charles I of Hungary, the castle of Visegrád, the seat of the Hungarian monarchs was the scene of the royal summit of the Kings of Poland, Bohemia and Hungary.[24] They agreed to cooperate closely in the field of politics and commerce, inspiring their late successors to launch a successful Central European initiative.[24]

In the Middle Ages, countries in Central Europe adopted Magdeburg rights.

Before World War I

Before 1870, the industrialization that had developed in Western and Central Europe and the United States did not extend in any significant way to the rest of the world. Even in Eastern Europe, industrialization lagged far behind. Russia, for example, remained largely rural and agricultural, and its autocratic rulers kept the peasants in serfdom.[26] The concept of Central Europe was already known at the beginning of the 19th century,[27] but its real life began in the 20th century and immediately became an object of intensive interest. However, the very first concept mixed science, politics and economy – it was strictly connected with intensively growing German economy and its aspirations to dominate a part of European continent called Mitteleuropa. The German term denoting Central Europe was so fashionable that other languages started referring to it when indicating territories from Rhine to Vistula, or even Dnieper, and from the Baltic Sea to the Balkans.[28] An example of that-time vision of Central Europe may be seen in J. Partsch’s book of 1903.[29]

On 21 January 1904 – Mitteleuropäischer Wirtschaftsverein (Central European Economic Association) was established in Berlin with economic integration of Germany and Austria–Hungary (with eventual extension to Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands) as its main aim. Another time, the term Central Europe became connected to the German plans of political, economic and cultural domination. The "bible" of the concept was Friedrich Naumann’s book Mitteleuropa[30] in which he called for an economic federation to be established after the war. Naumann's idea was that the federation would have at its center Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire but would also include all European nations outside the Anglo-French alliance, on one side, and Russia, on the other.[31] The concept failed after the German defeat in World War I and the dissolution of Austria–Hungary. The revival of the idea may be observed during the Hitler era.

Interwar period

According to Emmanuel de Martonne, in 1927 the Central European countries included: Austria, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Switzerland. Italy and Yugoslavia are not considered by the author to be Central European because they are located mostly outside Central Europe. The author use both Human and Physical Geographical features to define Central Europe.[34]

The interwar period (1918–1939) brought new geopolitical system and economic and political problems, and the concept of Central Europe took a different character. The centre of interest was moved to its eastern part – the countries that have (re)appeared on the map of Europe: Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Poland. Central Europe ceased to be the area of German aspiration to lead or dominate and became a territory of various integration movements aiming at resolving political, economic and national problems of "new" states, being a way to face German and Soviet pressures. However, the conflict of interests was too big and neither Little Entente nor Intermarium (Międzymorze) ideas succeeded.

The interwar period brought new elements to the concept of Central Europe. Before World War I, it embraced mainly German states (Germany, Austria), non-German territories being an area of intended German penetration and domination – German leadership position was to be the natural result of economic dominance.[27] After the war, the Eastern part of Central Europe was placed at the centre of the concept. At that time the scientists took interest in the idea: the International Historical Congress in Brussels in 1923 was committed to Central Europe, and the 1933 Congress continued the discussions.[35]

Hungarian scholar Magda Adam wrote in her study Versailles System and Central Europe (2006): "Today we know that the bane of Central Europe was the Little Entente, military alliance of Czechoslovakia, Romania and Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia), created in 1921 not for Central Europe's cooperation nor to fight German expansion, but in a wrong perceived notion that a completely powerless Hungary must be kept down".[35]

The avant-garde movements of Central Europe were an essential part of modernism’s evolution, reaching its peak throughout the continent during the 1920s. The Sourcebook of Central European avantgards (Los Angeles County Museum of Art) contains primary documents of the avant-gardes in Austria, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Yugoslavia from 1910 to 1930.[33] The manifestos and magazines of Western European radical art circles are well known to Western scholars and are being taught at primary universities of their kind in the western world.

Mitteleuropa

The German term Mitteleuropa (or alternatively its literal translation into English, Middle Europe[36]) is an ambiguous German concept.[36] It is sometimes used in English to refer to an area somewhat larger than most conceptions of 'Central Europe'; it refers to territories under Germanic cultural hegemony until World War I (encompassing Austria–Hungary and Germany in their pre-war formations but usually excluding the Baltic countries north of East Prussia). According to Fritz Fischer Mitteleuropa was a scheme in the era of the Reich of 1871–1918 by which the old imperial elites had allegedly sought to build a system of German economic, military and political domination from the northern seas to the Near East and from the Low Countries through the steppes of Russia to the Caucasus.[37] Later on, professor Fritz Epstein argued the threat of a Slavic "Drang nach Westen" (Western expansion) had been a major factor in the emergence of a Mitteleuropa ideology before the Reich of 1871 ever came into being.[38]

In Germany the connotation was also sometimes linked to the pre-war German provinces east of the Oder-Neisse line which were lost as the result of World War II, annexed by People's Republic of Poland and the Soviet Union, and ethnically cleansed of Germans by communist authorities and forces (see expulsion of Germans after World War II) due to Yalta Conference and Potsdam Conference decisions. In this view Bohemia and Moravia, with its dual Western Slavic and Germanic heritage, combined with the historic element of the "Sudetenland", is a core region illustrating the problems and features of the entire Central European region.

The term Mitteleuropa conjures up negative historical associations among some elder people, although the Germans have not played an exclusively negative role in the region.[39] Most Central European Jews embraced the enlightened German humanistic culture of the 19th century.[40] German-speaking Jews from turn of the 20th century Vienna, Budapest and Prague became representatives of what many consider to be Central European culture at its best, though the Nazi version of "Mitteleuropa" destroyed this kind of culture instead.[36][40][41] However, the term "Mitteleuropa" is now widely used again in German education and media without negative meaning, especially since the end of communism. In fact, many people from the New states of Germany do not identify themselves as being part of Western Europe and therefore prefer the term "Mitteleuropa".

Central Europe behind the Iron Curtain

Following World War II, large parts of Europe that were culturally and historically Western became part of the Eastern bloc. Czech author Milan Kundera (emigrant to France) thus wrote in 1984 about the "Tragedy of Central Europe" in the New York Review of Books.[43] Consequently, the English term Central Europe was increasingly applied only to the westernmost former Warsaw Pact countries (East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary) to specify them as communist states that were culturally tied to Western Europe.[44] This usage continued after the end of the Warsaw Pact when these countries started to undergo transition.

The post-World War II period brought blocking of the research on Central Europe in the Eastern Bloc countries, as its every result proved the dissimilarity of Central Europe, which was inconsistent with the Stalinist doctrine. On the other hand, the topic became popular in Western Europe and the United States, much of the research being carried out by immigrants from Central Europe.[45] At the end of the communism, publicists and historians in Central Europe, especially anti-communist opposition, came back to their research.[46]

According to Karl A. Sinnhuber (Central Europe: Mitteleuropa: Europe Centrale: An Analysis of a Geographical Term)[42] most Central European states were unable to preserve their political independence and became Soviet Satellite Europe. Besides Austria, only marginal Central European states of Finland and Yugoslavia did preserve their political sovereignty to a certain degree, being left out from any military alliances in Europe.

According to Meyers Enzyklopädisches Lexikon,[47] Central Europe is a part of Europe composed by the surface of the Austria, Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Germany, Hungary, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Poland, Romania and Switzerland, and northern marginal regions of Italy and Yugoslavia (northern states - Croatia and Slovenia), as well as northeastern France.

Current views

Rather than a physical entity, Central Europe is a concept of shared history which contrasts with that of the surrounding regions. The issue of how to name and define the Central European region is subject to debates. Very often, the definition depends on the nationality and historical perspective of its author.

Main propositions, gathered by Jerzy Kłoczowski, include:[48]

- West-Central and East-Central Europe – this conception, presented in 1950,[49] distinguishes two regions in Central Europe: German West-Centre, with imperial tradition of the Reich, and the East-Centre covered by variety of nations from Finland to Greece, placed between great empires of Scandinavia, Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union.

- Central Europe as the area of cultural heritage of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth – Ukrainian, Belarusian and Lithuanian historians, in cooperation (since 1990) with Polish historians, insist on the importance of the concept.

- Central Europe as a region connected to the Western civilisation for a very long time, including countries like the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Kingdom of Croatia, Holy Roman Empire, later German Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy, the Kingdom of Hungary and the Crown of Bohemia. Central Europe understood in this way borders on Russia and South-Eastern Europe, but the exact frontier of the region is difficult to determine.

- Central Europe as the area of cultural heritage of the Habsburg Empire (later Austria-Hungary) – a concept which is popular in regions along the Danube River.

- A concept underlining the links connecting Belarus and Ukraine with Russia and treating the Russian Empire together with the whole Slavic Orthodox population as one entity – this position is taken by the Russian historiography.

- A concept putting an accent on the links with the West, especially from the 19th century and the grand period of liberation and formation of Nation-states – this idea is represented by in the South-Eastern states, which prefer the enlarged concept of the "East Centre" expressing their links with the Western culture.

According to Ronald Tiersky, the 1991 summit held in Visegrád, Hungary and attended by the Polish, Hungarian and Czechoslovak presidents was hailed at the time as a major breakthrough in Central European cooperation, but the Visegrád Group became a vehicle for coordinating Central Europe's road to the European Union, while development of closer ties within the region languished.[50]

Peter J. Katzenstein described Central Europe as a way station in a Europeanization process that marks the transformation process of the Visegrád Group countries in different, though comparable ways.[51] According to him, in Germany's contemporary public discourse "Central European identity" refers to the civilizational divide between Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy.[51] He says there's no precise, uncontestable way to decide whether the Baltic states, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Romania, and Bulgaria are parts of Central Europe or not.[52]

Lonnie R. Johnson points out criteria to distinguish Central Europe from Western, Eastern and Southeast Europe:[53]

- One criterion for defining Central Europe is the frontiers of medieval empires and kingdoms that largely correspond to the religious frontiers between the Roman Catholic West and the Orthodox East.[54] The pagans of Central Europe were converted to Roman Catholicism while in Southeastern and Eastern Europe they were brought into the fold of the Eastern Orthodox Church.[54]

- Multinational empires were a characteristic of Central Europe.[55] Hungary and Poland, small and medium-size states today, were empires during their early histories.[55] The historical Kingdom of Hungary was until 1918 three times larger than Hungary is today,[55] while Poland was the largest state in Europe in the 16th century.[55] Both these kingdoms housed a wide variety of different peoples.[55]

He also thinks that Central Europe is a dynamical historical concept, not a static spatial one. For example, Lithuania, a fair share of Belarus and western Ukraine are in Eastern Europe today, but 230 years ago they were in Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.[55]

Johnson's study on Central Europe received acclaim and positive reviews[56][57] in the scientific community. However, according to Romanian researcher Maria Bucur this very ambitious project suffers from the weaknesses imposed by its scope (almost 1600 years of history).[58]

The Columbia Encyclopedia defines Central Europe as: Germany, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, Austria, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary.[59] The World Factbook[17] Encyclopædia Britannica and Brockhaus Enzyklopädie use the same definition adding Slovenia too. Encarta Encyclopedia does not clearly define the region, but places the same countries into Central Europe in its individual articles on countries, adding Slovenia in "south central Europe".[60]

The German Encyclopaedia Meyers Grosses Taschenlexikon (English: Meyers Big Pocket Encyclopedia), 1999, defines Central Europe as the central part of Europe with no precise borders to the East and West. The term is mostly used to denominate the territory between the Schelde to Vistula and from the Danube to the Moravian Gate. Usually the countries considered to be Central European are Austria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, Switzerland; in the broader sense Romania too, occasionally also Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.

.png)

States

The comprehension of the concept of Central Europe is an ongoing source of controversy,[61] though the Visegrád Group constituents are almost always included as de facto C.E. countries.[62] Although views on which countries belong to Central Europe are vastly varied, according to many sources (see section Current views on Central Europe) the region includes the states listed in the sections below.

Austria

Austria Czech Republic

Czech Republic Germany

Germany Hungary

Hungary Poland

Poland Slovakia

Slovakia Slovenia[63] (sometimes placed in Southeastern Europe)[64]

Slovenia[63] (sometimes placed in Southeastern Europe)[64] Switzerland

Switzerland

Depending on context, Central European countries are sometimes grouped as Eastern, Western European countries, collectively or individually[65][66][67][68] but some place them in Eastern Europe instead:,[65][66][67] for instance Austria can be referred to as Central European, as well as Eastern European[69] or Western European.[70]

Other countries and regions

Some sources also add neighbouring countries for historical (the former Austro-Hungarian and German Empires, and modern Baltic states), based on geographical and/or cultural reasons:

Croatia[18][71][72][73][74] (alternatively placed in Southeastern Europe)[75][76]

Croatia[18][71][72][73][74] (alternatively placed in Southeastern Europe)[75][76] Romania (Transylvania[77] and Bukovina[78])[79][80][81]

Romania (Transylvania[77] and Bukovina[78])[79][80][81]

The Baltic states, geographically located in Northern Europe, have been considered part of Central Europe in the German tradition of the term, Mittleuropa. Benelux countries are generally considered a part of Western Europe, rather than Central Europe. Nevertheless, they are occasionally mentioned in the Central European context due to cultural, historical and linguistic ties.

Following states or some of their regions may sometimes be included in Central Europe:

Serbia[82][83][84][85]

Serbia[82][83][84][85]  Italy (South Tyrol, Trentino, Trieste and Gorizia, Friuli, occasionally all of Northern Italy)

Italy (South Tyrol, Trentino, Trieste and Gorizia, Friuli, occasionally all of Northern Italy) Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein Switzerland

Switzerland Ukraine (Transcarpathia,[86] Galicia and Northern Bukovina[78])

Ukraine (Transcarpathia,[86] Galicia and Northern Bukovina[78])

Geography

Geography defines Central Europe's natural borders with the neighbouring regions to the North across the Baltic Sea namely the Northern Europe (or Scandinavia), and to the South across the Alps, the Apennine peninsula (or Italy), and the Balkan peninsula[87] across the Soča-Krka-Sava-Danube line. The borders to Western Europe and Eastern Europe are geographically less defined and for this reason the cultural and historical boundaries migrate more easily West-East than South-North. The Rhine river which runs South-North through Western Germany is an exception.

Southwards, the Pannonian Plain is bounded by the rivers Sava and Danube- and their respective floodplains.[88] The Pannonian Plain stretches over the following countries: Austria, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia, and touches borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Republika Srpska) and Ukraine ("peri- Pannonian states").

As southeastern division of the Eastern Alps,[89] the Dinaric Alps extend for 650 kilometres along the coast of the Adriatic Sea (northwest-southeast), from the Julian Alps in the northwest down to the Šar-Korab massif, north-south. According to the Freie Universitaet Berlin, this mountain chain is classified as South Central European.[90]

The Central European flora region stretches from Central France (the Massif Central) to Central Romania (Carpathians) and Southern Scandinavia.[91]

At times, the term "Central Europe" denotes a geographic definition as the Danube region in the heart of the continent, including the language and culture areas which are today included in the states of Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and usually also Austria and Germany, but never Russia and other countries of the former Soviet Union towards the Ural mountains.[92]

Statistics

Data

- Area: 1.036.370 km2 (2012)

- Population: (calculated data) 163.518.571 (July 2012)

- Population density: (calculated data) 157.78/km2 (2012)

- GDP (PPP) per capita: USD $34.444 (2012)

- Life expectancy: (calculated data) 78.32-year (2012)

- Unemployment rate: 8.2% (2012)

- Fertility rate: 1.41 births/woman (2012)

- Human Development Index: 0.874 (2012) (very high)

- Globalization Index (regional): 80.09 (2013)

[93]

[93]

Demography

Central Europe is one of continent's most populous regions. It includes countries of varied sizes, ranging from tiny Liechtenstein to Germany, the largest European country by population (that is entirely placed in Europe). Demographic figures for countries entirely located within notion of Central Europe ("the core countries") number around 165 million people, out of which around 82 million are residents of Germany.[94] Other populations include: Poland with around 38.5 million residents,[95] Czech Republic at 10.5 million,[96] Hungary at 10 million,[97] Austria with 8.5 million, Switzerland with its 8 million inhabitants,[98] Slovakia at 5.4 million,[99] Croatia with its 4.3 million[100] residents, Slovenia at 2 million (2014 estimate)[101] and Liechtenstein at a bit less than 40,000.[102]

If the countries which are occasionally included in Central Europe were counted in, partially or in whole – Romania (20 million), Lithuania (2.9 million), Latvia (2 million), Estonia (1.3 million) – it would contribute to the rise of between 25–35 million, depending on whether regional or integral approach was used.[103] If smaller, western and eastern historical parts of Central Europe would be included in the demographic corpus, further 20 million people of different nationalities would also be added in the overall count, it would surpass the 200 million people figure.

Economy

Currencies

Currently, the members of the Eurozone include Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Romania use their currencies (Croatian kuna, Czech koruna, Hungarian forint, Polish złoty, Romanian leu), but are obliged to adopt the Euro.

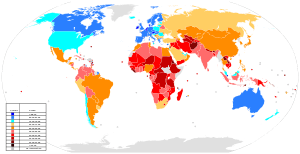

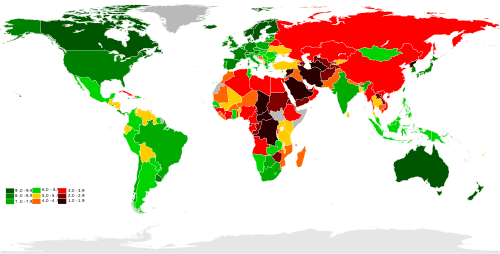

Human Development Index

| Very High | Low |

| High | Data unavailable |

| Medium |

Countries in descending order of Human Development Index (2014 data):

Switzerland: 0.917 (ranked 3)

Switzerland: 0.917 (ranked 3) Germany: 0.911 (ranked 6)

Germany: 0.911 (ranked 6) Austria: 0.881 (ranked 21)

Austria: 0.881 (ranked 21) Slovenia: 0.874 (ranked 25)

Slovenia: 0.874 (ranked 25) Liechtenstein: 0.889 (ranked 18)

Liechtenstein: 0.889 (ranked 18) Czech Republic: 0.861 (ranked 28)

Czech Republic: 0.861 (ranked 28) Poland: 0.834 (ranked 35)

Poland: 0.834 (ranked 35) Slovakia: 0.830 (ranked 37)

Slovakia: 0.830 (ranked 37) Hungary: 0.818 (ranked 43)

Hungary: 0.818 (ranked 43) Croatia: 0.812 (ranked 47)

Croatia: 0.812 (ranked 47) Romania: 0.785 (ranked 54)

Romania: 0.785 (ranked 54)

Globalisation

The index of globalization in Central European countries (2014 data):[104]

Austria: 90.48 (ranked 4)

Austria: 90.48 (ranked 4) Hungary: 85.91 (ranked 9)

Hungary: 85.91 (ranked 9) Switzerland: 85.74 (ranked 11)

Switzerland: 85.74 (ranked 11) Czech Republic: 83.97 (ranked 16)

Czech Republic: 83.97 (ranked 16) Slovakia: 83.55 (ranked 18)

Slovakia: 83.55 (ranked 18) Poland: 79.52 (ranked 25)

Poland: 79.52 (ranked 25) Germany: 79.47 (ranked 26)

Germany: 79.47 (ranked 26) Slovenia: 76.86 (ranked 29)

Slovenia: 76.86 (ranked 29) Croatia: 74.92 (ranked 33)

Croatia: 74.92 (ranked 33) Romania: 72.24 (ranked 38)

Romania: 72.24 (ranked 38) Liechtenstein: 29.23 (ranked 180)

Liechtenstein: 29.23 (ranked 180)

Prosperity Index

Legatum Prosperity Index demonstrates an average and high level of prosperity in Central Europe (2014 data):[105]

Switzerland (ranked 2)

Switzerland (ranked 2) Germany (ranked 14)

Germany (ranked 14) Austria (ranked 15)

Austria (ranked 15) Slovenia (ranked 24)

Slovenia (ranked 24) Czech Republic (ranked 29)

Czech Republic (ranked 29) Poland (ranked 31)

Poland (ranked 31) Slovakia (ranked 35)

Slovakia (ranked 35) Hungary (ranked 39)

Hungary (ranked 39) Croatia (ranked 50)

Croatia (ranked 50) Romania (ranked 60)

Romania (ranked 60)

Corruption

| 90–100 | 60–69 | 30–39 | 0–9 |

| 80–89 | 50–59 | 20–29 | No information |

| 70–79 | 40–49 | 10–19 |

Most countries in Central Europe score tend to score above the average in the Corruption Perceptions Index (2014 data):[106]

Switzerland (ranked 5, tied)

Switzerland (ranked 5, tied) Germany (ranked 12, tied)

Germany (ranked 12, tied) Austria (ranked 23, tied)

Austria (ranked 23, tied) Poland (ranked 35, tied)

Poland (ranked 35, tied) Slovenia (ranked 39, tied)

Slovenia (ranked 39, tied) Hungary (ranked 47)

Hungary (ranked 47) Czech Republic (ranked 53, tied)

Czech Republic (ranked 53, tied) Slovakia (ranked 54)

Slovakia (ranked 54) Croatia (ranked 61, tied)

Croatia (ranked 61, tied)

According to the Bribe Payers Index, released yearly since 1995 by the Berlin-based NGO Transparency International, Germany and Switzerland, the only two Central European countries examined in the study, were respectively ranked 2nd and 4th in 2011.[107]

Infrastructure

Industrialisation occurred early in Central Europe. That caused construction of rail and other types of infrastructure.

Rail

Central Europe contains the continent's earliest railway systems, whose greatest expansion was recorded in Austro-Hungarian and German territories between 1860-1870s.[108] By the mid-19th century Berlin, Vienna, and Buda/Pest were focal points for network lines connecting industrial areas of Saxony, Silesia, Bohemia, Moravia and Lower Austria with the Baltic (Kiel, Szczecin) and Adriatic (Rijeka, Trieste).[108] Rail infrastructure in Central Europe remains the densest in the world. Railway density, with total length of lines operated (km) per 1,000 km2, is the highest in the Czech Republic (198.6), Poland (121.0), Slovenia (108.0), Germany (105.5), Hungary (98.7), Romania (85.9), Slovakia (73.9) and Croatia (72.5).[109][110] when compared with most of Europe and the rest of the world.[111][112]

River transport and canals

Before the first railroads appeared in the 1840s, river transport constituted the main means of communication and trade.[108] Earliest canals included Plauen Canal (1745), Finow Canal, and also Bega Canal (1710) which connected Timișoara to Novi Sad and Belgrade via Danube.[108] The most significant achievement in this regard was the facilitation of navigability on Danube from the Black sea to Ulm in the 19th century.

Branches

Compared to most of Europe, the economies of Austria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia and Switzerland tend to demonstrate high complexity. Industrialisation has reached Central Europe relatively early: Luxembourg and Germany by 1860, the Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia and Switzerland by 1870, Austria, Croatia, Hungary, Liechtenstein, Romania and Slovenia by 1880.[113]

Agriculture

Central European countries are some of the most significant food producers in the world. Germany is the world's largest hops producer with 34.27% share in 2010,[114] third producer of rye and barley, 5th rapeseed producer, sixth largest milk producer, and fifth largest potato producer. Poland is the world's largest triticale producer, second largest producer of raspberry, currant, third largest of rye, the fifth apple and buckwheat producer, and seventh largest producer of potatoes. The Czech Republic is world's fourth largest hops producer and 8th producer of triticale. Hungary is world's fifth hops and seventh largest triticale producer. Slovenia is world's sixth hops producer.

Tourism

Central European countries, especially Austria, Croatia, Germany and Switzerland are some of the most competitive tourism destinations.[115] Poland is presently a major destination for outsourcing.[116]

Outsourcing destination

Kraków, Warsaw, and Wroclaw, Poland; Prague and Brno, Czech Republic; Budapest, Hungary; Bucharest, Romania; Bratislava, Slovakia; Ljubljana, Slovenia and Zagreb, Croatia are among the world's top 100 outsourcing destinations.[117]

Education

Central European countries are very literate. All of them have the literacy rate of 96% or over (for both sexes):

| Country | Literacy rate (all) | Male | Female | Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| | 84.1% | 88.6% | 79.7% | age 15 and over can read and write (2010 est.) |

| | 100% | 100% | 100% | age 10 and over can read and write |

| | 99.7% | 99.9% | 99.6% | age 15 and over can read and write (2011 est.) |

| | 99.7% | 99.7% | 99.7% | (2010 est.) |

| | 99.6% | 99.7% | 99.6% | age 15 and over can read and write (2004) |

| | 99% | 99% | 99% | (2011 est.) |

| | 99% | 99% | 99% | age 15 and over can read and write (2003 est.) |

| | 99% | 99.2% | 98.9% | age 15 and over can read and write (2011 est.) |

| | 99% | 99% | 99% | age 15 and over can read and write (2003 est.) |

| | 98.9% | 99.5% | 98.3% | age 15 and over can read and write (2011 est.) |

| | 98% | N/A | N/A | age 15 and over can read and write |

| | 97.7% | 98.3% | 97.1% | age 15 and over can read and write (2011 est.) |

Languages

Languages taught as the first language in Central Europe are: Croatian, Czech, French, German, Hungarian, Italian, Polish, Romansh, Slovak and Slovenian. The most popular language taught at schools in Central Europe as foreign languages are: English, French and German.[118]

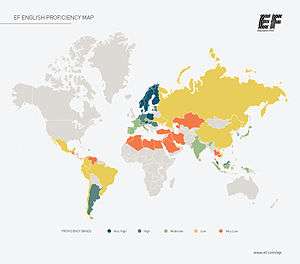

Proficiency in English is ranked as high or moderate, according to the EF English Proficiency Index:[119]

Slovenia (position 6)

Slovenia (position 6) Luxembourg (position 8)

Luxembourg (position 8) Poland (position 9)

Poland (position 9) Austria (position 10)

Austria (position 10) Germany (position 11)

Germany (position 11) Romania (position 16)

Romania (position 16) Hungary (position 21)

Hungary (position 21) Czech Republic (position 18)

Czech Republic (position 18) Switzerland (position 19)

Switzerland (position 19) Slovakia (position 25)

Slovakia (position 25) Croatia (not ranked)

Croatia (not ranked) Liechtenstein (not ranked)

Liechtenstein (not ranked)

Other languages, also popular (spoken by over 5% as a second language):[118]

- Croatian in Slovenia (61%)

- Czech in Slovakia (82%)[120]

- French in Romania (17%), Germany (14%) and Austria (11%)

- German in Slovenia (42%), Croatia (34%), Slovakia (22%), Poland (20%), Hungary (18%), the Czech Republic (15%) and Romania (5%)

- Hungarian in Romania (9%) and Slovakia (12%)[121]

- Italian in Croatia (14%), Slovenia (12%), Austria (9%) and Romania (7%)

- Russian in Poland (28%), Slovakia (17%), the Czech Republic (13%) and Germany (6%)

- Polish in Slovakia (5%)

- Slovak in the Czech Republic (16%)

- Spanish in Romania (5%)

Scholastic performance

Student performance has varied across Central Europe, according to the Programme for International Student Assessment. In the last study, countries scored medium, below or over the average scores in three fields studied.[122]

In maths:

-

Liechtenstein (position 8) – above the OECD average

Liechtenstein (position 8) – above the OECD average -

Switzerland (position 9) – above the OECD average

Switzerland (position 9) – above the OECD average -

Poland (position 14) – above the OECD average

Poland (position 14) – above the OECD average -

Germany (position 16) – above the OECD average

Germany (position 16) – above the OECD average -

Austria (position 18) – above the OECD average

Austria (position 18) – above the OECD average -

Slovenia (position 21) – above the OECD average

Slovenia (position 21) – above the OECD average -

Czech Republic (position 24) – similar to the OECD average

Czech Republic (position 24) – similar to the OECD average -

Slovakia (position 35) – below the OECD average

Slovakia (position 35) – below the OECD average -

Hungary (position 39) – below the OECD average

Hungary (position 39) – below the OECD average -

Croatia (position 40) – below the OECD average

Croatia (position 40) – below the OECD average -

Serbia (position 43) – below the OECD average

Serbia (position 43) – below the OECD average -

Romania (position 45) – below the OECD average

Romania (position 45) – below the OECD average

In the sciences:

-

Poland (position 9) – above the OECD average

Poland (position 9) – above the OECD average -

Liechtenstein (position 10) – above the OECD average

Liechtenstein (position 10) – above the OECD average -

Germany (position 12) – above the OECD average

Germany (position 12) – above the OECD average -

Switzerland (position 19) – above the OECD average

Switzerland (position 19) – above the OECD average -

Slovenia (position 20) – above the OECD average

Slovenia (position 20) – above the OECD average -

Czech Republic (position 22) – above the OECD average

Czech Republic (position 22) – above the OECD average -

Austria (position 23) – similar to the OECD average

Austria (position 23) – similar to the OECD average -

Hungary (position 33) – below the OECD average

Hungary (position 33) – below the OECD average -

Croatia (position 35) – below the OECD average

Croatia (position 35) – below the OECD average -

Slovakia (position 40) – below the OECD average

Slovakia (position 40) – below the OECD average -

Romania (position 49) – below the OECD average

Romania (position 49) – below the OECD average

In reading:

-

Poland (position 10) – above the OECD average

Poland (position 10) – above the OECD average -

Liechtenstein (position 11) – above the OECD average

Liechtenstein (position 11) – above the OECD average -

Switzerland (position 17) – above the OECD average

Switzerland (position 17) – above the OECD average -

Germany (position 19) – above the OECD average

Germany (position 19) – above the OECD average -

Czech Republic (position 26) – similar to the OECD average

Czech Republic (position 26) – similar to the OECD average -

Austria (position 27) – below the OECD average

Austria (position 27) – below the OECD average -

Hungary (position 33) – below the OECD average

Hungary (position 33) – below the OECD average -

Croatia (position 35) – below the OECD average

Croatia (position 35) – below the OECD average -

Slovenia (position 38) – below the OECD average

Slovenia (position 38) – below the OECD average -

Romania (position 50) – below the OECD average

Romania (position 50) – below the OECD average

Higher education

Universities

.jpg)

The first university east of France and north of the Alps was the Charles University in Prague established in 1347 or 1348 by Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and modeled on the University of Paris, with the full number of faculties (law, medicine, philosophy and theology).[123] The list of Central Europe's oldest universities in continuous operation, established by 1500, include (by their dates of foundation):

Charles University in Prague,[124] Czech Republic (1348)

Charles University in Prague,[124] Czech Republic (1348) Jagiellonian University[125] in Kraków, Poland (1364)

Jagiellonian University[125] in Kraków, Poland (1364) University of Vienna[126] in Vienna, Austria (1365)

University of Vienna[126] in Vienna, Austria (1365) University of Pécs[127] in Pécs, Hungary (1367)

University of Pécs[127] in Pécs, Hungary (1367) Heidelberg University[128] in Heidelberg, Germany (1386)

Heidelberg University[128] in Heidelberg, Germany (1386) Cologne University[129] in Cologne, Germany (1388)

Cologne University[129] in Cologne, Germany (1388) University of Zadar[130] in Zadar, Croatia (1396)

University of Zadar[130] in Zadar, Croatia (1396) University of Leipzig[131] in Leipzig, Germany (1409)

University of Leipzig[131] in Leipzig, Germany (1409) University of Rostock[132] in Rostock, Germany (1419)

University of Rostock[132] in Rostock, Germany (1419) University of Greifswald[133] in Greifswald, Germany (1456)

University of Greifswald[133] in Greifswald, Germany (1456) University of Freiburg[134] in Freiburg, Germany (1457)

University of Freiburg[134] in Freiburg, Germany (1457) University of Basel[135] in Basel, Switzerland (1460)

University of Basel[135] in Basel, Switzerland (1460) Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich[136] in Munich, Germany (1472)

Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich[136] in Munich, Germany (1472) University of Tübingen[137] in Tübingen, Germany (1477)

University of Tübingen[137] in Tübingen, Germany (1477)

Central European University

The Central European University (CEU) is a graduate-level, English-language university promoting a distinctively Central European perspective. It was established in 1991 by the Hungarian philanthropist George Soros, who has provided an endowment of US$880 million, making the university one of the wealthiest in Europe.[138] In the academic year 2013/2014, the CEU had 1,381 students from 93 countries and 388 faculty members from 58 countries.[139]

Regional exchange program

Central European Exchange Program for University Studies (CEEPUS) is an international exchange program for students and teachers teaching or studying in participating countries. Its current members include (year it joined for the first time in brackets):[140]

Albania (2006)

Albania (2006) Austria (2005)

Austria (2005) Bosnia and Herzegovina (2008)

Bosnia and Herzegovina (2008) Bulgaria (2005)

Bulgaria (2005) Croatia (2005)

Croatia (2005) Czech Republic (2005)

Czech Republic (2005) Hungary (2005)

Hungary (2005)- Kosovo*[141] (2008)

Macedonia (2006)

Macedonia (2006) Moldova (2011)

Moldova (2011) Montenegro (2006)

Montenegro (2006) Poland (2005)

Poland (2005) Romania (2005)

Romania (2005) Serbia (2005)

Serbia (2005) Slovakia (2005)

Slovakia (2005) Slovenia (2005)

Slovenia (2005)

Culture and society

Research centers of Central European literature include Harvard (Cambridge, MA),[142] Purdue University[143]

Architecture

Central European architecture has been shaped by major European styles including but not limited to: Brick Gothic, Rococo, Secession (art) and Modern architecture. Four Central European countries are amongst those countries with higher numbers of World Heritage Sites:

Germany (position 4th, 38 sites)

Germany (position 4th, 38 sites) Poland (position 17th, 15 sites)

Poland (position 17th, 15 sites) Czech Republic (position 19th, 12 sites)

Czech Republic (position 19th, 12 sites) Switzerland (position 20th, 11 sites)

Switzerland (position 20th, 11 sites)

Beliefs

Central European countries are mostly Roman Catholic (Austria, Croatia, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia) or mixed Catholic and Protestant, (Germany, Hungary and Switzerland). Large Protestant groups include Lutheran and Calvinist. Significant populations of Eastern Catholicism and Old Catholicism are also prevalent throughout Central Europe. Central Europe has been a centre of Protestantism in the past; however, it has been mostly eradicated by the Counterreformation.[144][145][146] The Czech Republic (Bohemia) was historically the first Protestant country, then violently recatholised, and now overwhelmingly non-religious with the largest number of religious being Catholic (10.3%). Romania and Serbia are mostly Eastern Orthodox with significant Protestant and Catholic minorities.

In some of these countries, there is a number of atheists, undeclared and non-religious people: the Czech Republic (non-religious 34.2% and undeclared 45.2%), Germany (non-religious 38%), Slovenia (atheist 30.2%), Luxembourg (25% non-religious), Switzerland (20.1%), Hungary (27.2% undeclared, 16.7% "non-religious" and 1.5% atheists), Slovakia (atheists and non-religious 13.4%, "not specified" 10.6%) Austria (19.7% of "other or none"), Liechtenstein (10.6% with no religion), Croatia (4%) and Poland (3% of non-believers/agnostics and 1% of undeclared).

-

St. Vitus Cathedral, Prague (Catholic), Czech Republic

-

Zagreb Cathedral, Zagreb (Catholic), Croatia

-

St. Mary's Basilica, Krakow (Catholic), Poland

-

Jesuit Church, Lucerne (Catholic), Switzerland

-

Berlin Cathedral (Lutheran), Germany

-

Grossmünster (Calvinist), Switzerland

-

Metropolitan Cathedral, Iași (Orthodox), Romania

-

Abbey of Saint Gall (Catholic), Switzerland

-

Cologne Cathedral (Catholic), Germany

-

Prejmer fortified church (Lutheran), Romania

-

Cathedral of Hajdúdorog (Eastern Catholic), Hungary

-

Vaduz Cathedral (Catholic), Liechtenstein

-

St. Elisabeth Cathedral in Košice (Catholic), Slovakia

-

Evangelical church in Partizánska Ľupča (Lutheran), Slovakia

Cuisine

Central European cuisine has evolved through centuries due to social and political change. Most countries share many dishes. The most popular dishes typical to Central Europe are sausages and cheeses, where the earliest evidence of cheesemaking in the archaeological record dates back to 5,500 BCE (Kujawy, Poland).[147] Other foods widely associated with Central Europe are goulash and beer. List of countries by beer consumption per capita is led by the Czech Republic, followed by Germany and Austria. Poland comes 5th, Croatia 7th and Slovenia 13th.

Human rights

History

Human rights have a long tradition in Central Europe. In 1222 Hungary defined for the first time the rights of the nobility in its "Golden Bull". In 1264 the Statute of Kalisz and the General Charter of Jewish Liberties introduced numerous rights for the Jews in Poland, granting them de facto autonomy. In 1783 for the first time, Poland forbid corporal punishment of children in schools. In the same year, a German state of Baden banned slavery.

On the other hand, there were also major regressions, such as "Nihil novi" in Poland in 1505 which forbade peasants from leaving their land without permission from their feudal lord.

Present

Generally, the countries in the region are progressive on the issue of human rights: death penalty is illegal in all of them, corporal punishment is outlawed in most of them and people of both genders can vote in elections. Nevertheless, Central European countries struggle to adopt new generations of human rights, such as same-sex marriage. Austria, the Czech Republic, Germany, Poland and Romania also have a history of participation in the CIA's extraordinary rendition and detention program, according to the Open Society Foundation.[148][149]

Literature

Regional writing tradition revolves around the turbulent history of the region, as well as its cultural diversity,[150][151] and its existence is sometimes challenged.[152]

Specific courses on Central European literature are taught at Stanford University,[153] Harvard University[154] and Jagiellonian University[155] The as well as cultural magazines dedicated to regional literature.[156]

Angelus Central European Literature Award is an award worth 150,000.00 PLN (about $50,000 or £30,000) for writers originating from the region.[157]

Media

There is a whole spectrum of media active in the region: newspapers, television and internet channels, radio channels, internet websites etc. Central European media are regarded as free, according to the Press Freedom Index. Some of the top scoring countries are in Central Europe include:[158]

Austria (position 7)

Austria (position 7) Germany (position 12)

Germany (position 12) Czech Republic (position 13)

Czech Republic (position 13) Slovakia (position 14)

Slovakia (position 14) Poland (position 18)

Poland (position 18) Luxembourg (position 19)

Luxembourg (position 19) Switzerland (position 20)

Switzerland (position 20) Liechtenstein (position 27)

Liechtenstein (position 27) Slovenia (position 35)

Slovenia (position 35) Romania (position 52)

Romania (position 52) Croatia (position 58)

Croatia (position 58) Hungary (position 65)

Hungary (position 65) Serbia (position 67)

Serbia (position 67)

Sport

There is a number of Central European Sport events and leagues. They include:

- Central European Tour Miskolc GP (Hungary)*

- Central European Tour Budapest GP (Hungary)

- Central Europe Rally (Romania and Hungary)*

- Central European Football League (Austria, Croatia, Hungary, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia and Turkey)

- Central European International Cup (Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Switzerland and Yugoslavia; 1927-1960)

- Central Europe Throwdown*[159]

Football is one of the most popular sports. Countries of Central Europe had many great national teams throughout history and hosted several major competitions. Yugoslavia hosted UEFA Euro 1976 before the competition expanded to 8 teams and Germany (at that times as West Germany) hosted UEFA Euro 1988. Recently, 2008 and 2012 UEFA European Championships were held in Austria & Switzerland and Poland & Ukraine respectively. Germany hosted 2 FIFA World Cups (1974 and 2006) and are the current champions (as of 2018).[160][161][162]

Politics

Organisations

Central Europe is a birthplace of regional political organisations:

- Visegrad group

- Centrope

- Central European Initiative

- Central European Free Trade Agreement

- Middleeuropean Initiative

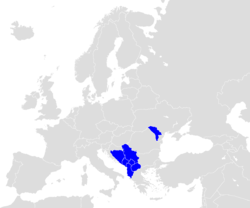

-

Central European Initiative

-

Visegrád Group

-

CEFTA founding states

-

CEFTA members in 2003, before joining the EU

-

Current CEFTA members

-

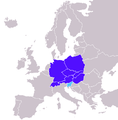

Central Europe according to Peter J. Katzenstein (1997)

Central Europe according to Peter J. Katzenstein (1997)

The Visegrád Group countries are referred to as Central Europe in the book[1]countries for which there's no precise, uncontestable way to decide whether they are parts of Central Europe or not[2] -

According to The Economist and Ronald Tiersky a strict definition of Central Europe means the Visegrád Group[3][4]

-

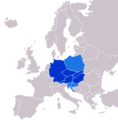

Map of Central Europe, according to Lonnie R. Johnson (2011)[5]Countries considered to be Central European only in the broader sense of the term.

-

Central European countries in Encarta Encyclopedia (2009)[6]

Central European countries in Encarta Encyclopedia (2009)[6]

Central European countriesSlovenia in "south central Europe" -

The Central European Countries according to Meyers Grosses Taschenlexikon (1999):

Countries usually considered Central EuropeanCentral European countries in the broader sense of the termCountries occasionally considered to be Central European -

Middle Europe (Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, 1998))

-

Central Europe according to Swansea University professors Robert Bideleux and Ian Jeffries (1998)[7]

-

Central Europe, as defined by E. Schenk (1950)[8]

-

Central Europe, according to Alice F. A. Mutton in Central Europe. A Regional and Human Geography (1961)

-

Central Europe according to Meyers Enzyklopaedisches Lexikon (1980)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Peter_J_p._6was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Peter_J_p._4was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Tiersky.2C_p._472was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

From_Visegrad_to_Mitteleuropawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Johnson, pp. 16

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

Encartawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Robert Bideleux; Ian Jeffries (10 April 2006). A History of Eastern Europe: Crisis and Change. Routledge. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-134-71984-6. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ^ Erich Schenk, Mitteleuropa. Düsseldorf, 1950

Democracy Index

Central Europe is a home to some of world's oldest democracies. However, most of them have been impacted by totalitarian rule, particularly Nazism (Germany, Austria, other occupied countries) and Communism. Most of Central Europe have been occupied and later allied with the USSR, often against their will through forged referendum (e.g., Polish people's referendum in 1946) or force (northeast Germany, Poland, Hungary et alia). Nevertheless, these experiences have been dealt in most of them. Most of Central European countries score very highly in the Democracy Index:[163]

-

Switzerland (position 6)

Switzerland (position 6) -

Luxembourg (position 11)

Luxembourg (position 11) -

Germany (position 13)

Germany (position 13) -

Austria (position 14)

Austria (position 14) -

Czech Republic (position 25)

Czech Republic (position 25) -

Slovenia (position 37)

Slovenia (position 37) -

Poland (position 40)

Poland (position 40) -

Slovakia (position 45)

Slovakia (position 45) -

Croatia (position 50)

Croatia (position 50) -

Hungary (position 51)

Hungary (position 51) -

Romania (position 57)

Romania (position 57) -

Liechtenstein (not listed)

Liechtenstein (not listed)

Global Peace Index

In spite of its turbulent history, Central Europe is currently one of world's safest regions. Most Central European countries are in top 20%:[164]

Austria (position 3)

Austria (position 3) Switzerland (position 5)

Switzerland (position 5) Czech Republic (position 11)

Czech Republic (position 11) Slovenia (position 14)

Slovenia (position 14) Germany (position 17)

Germany (position 17) Poland (position 23)

Poland (position 23) Hungary (position 22)

Hungary (position 22) Slovakia (position 19)

Slovakia (position 19) Croatia (position 26)

Croatia (position 26) Romania (position 35)

Romania (position 35) Liechtenstein (not listed)

Liechtenstein (not listed)

Central European Time

The time zone used in most parts of the European Union is a standard time which is 1 hour ahead of Coordinated Universal Time. It is commonly called Central European Time because it has been first adopted in central Europe (by year):

Hungary (1890)

Hungary (1890) Slovakia (1890)

Slovakia (1890) Czech Republic (1891)

Czech Republic (1891) Germany (1893)

Germany (1893) Austria (1893)

Austria (1893) Poland (1893[165])

Poland (1893[165]) Slovenia (1893)

Slovenia (1893) Switzerland (1894)

Switzerland (1894) Liechtenstein (1894)

Liechtenstein (1894)

In popular culture

Central Europe is mentioned in 35th episode of Lovejoy, entitled "The Prague Sun", filmed in 1992. While walking over the famous Charles Bridge, the main character, Lovejoy says: " I've never been to Prague before. Well, it is one of the great unspoiled cities in Central Europe. Notice: I said: "Central", not "Eastern"! The Czechs are a bit funny about that, they think of Eastern Europeans as turnip heads."[166]

Wes Anderson's Oscar-winning film The Grand Budapest Hotel is regarded as a fictionalised celebration of the 1930s in Central Europe[167] and region's musical tastes[168]

See also

- Central and Eastern Europe

- Central European Initiative

- Central European Time (CET)

- Central European University

- East-Central Europe

- Geographical centre of Europe

- Life zones of central Europe

- Międzymorze (Intermarum)

- Mitteleuropa

References

- ↑ "Regions, Regionalism, Eastern Europe by Steven Cassedy". New Dictionary of the History of Ideas, Charles Scribner's Sons. 2005. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ Lecture 14: The Origins of the Cold War. Historyguide.org. Retrieved on 29 October 2011.

- ↑ "Central Europe — The future of the Visegrad group". The Economist. 14 April 2005. Retrieved 7 March 2009.

- ↑ Agh 1998, pp. 2–8

- ↑ "Central European Identity in Politics — Jiří Pehe" (in Czech). Conference on Central European Identity, Central European Foundation, Bratislava. 2002. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ "Europe of Cultures: Cultural Identity of Central Europe". Europe House Zagreb, Culturelink Network/IRMO. 24 November 1996. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- 1 2 Comparative Central European culture. Purdue University Press. 2002. ISBN 9781557532404. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ "An Introduction to Central Europe: History, Culture, and Politics – Preparatory Course for Study Abroad Undergraduate Students at CEU". Central European University. Budapest. Fall 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-22.

- ↑ Ben Koschalka – content, Monika Lasota – design and coding. "To Be (or Not To Be) Central European: 20th Century Central and Eastern European Literature". Centre for European Studies of the Jagiellonian University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ "Ten Untaught Lessons about Central Europe-Charles Ingrao". HABSBURG Occasional Papers, No. 1. 1996. Archived from the original on 2003-12-14. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ "Introduction to the electronic version of Cross Currents". Scholarly Publishing Office of the University of Michigan Library. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ "History of the literary cultures of East-Central Europe: junctures and disjunctures in the 19th and 20th centuries, Volume 2".

- ↑ "When identity becomes an alibi (Institut Ramon Llull)" (PDF).

- ↑ "The Mice that Roared: Central Europe Is Reshaping Global Politics". Spiegel.de. 26 February 2006. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ "Which regions are covered?". European Regional Development Fund. Archived from the original on 2010-04-03. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ 2010 Human Development Index. (PDF) . Retrieved on 29 October 2011.

- 1 2 "The World Factbook: Field listing – Location". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- 1 2 Lonnie Johnson, Central Europe: Enemies, Neighbors, Friends, Oxford University Press

- ↑ Paul Robert Magocsi (2002). "The development of Central Europe (Chapter 11)". Historical Atlas of Central Europe. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802084869.

- ↑ Kasper von Greyerz (2007-10-22). Religion and Culture in Early Modern Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 38 –. ISBN 0198043848.

- ↑ Jean W Sedlar (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press. p. 161 –. ISBN 0295972912.

- ↑ Dumitran, Adriana (2010). "Uspořádání Evropy - duch kulturní jednoty na prahu vzniku novověké Evropy" [The shape of Europe. The spirit of unity through culture in the eve of Modern Europe] (in Czech). Czech Republic: Bibliography of the History of the Czech Lands, The Institute of History, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. (registration required (help)).

- ↑ László Zsinka. "Similarities and Differences in Polish and Hungarian History" (PDF). Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- 1 2 Halman, Loek; Wilhelmus Antonius Arts (2004). European values at the turn of the millennium. Brill Publishers. p. 120. ISBN 978-90-04-13981-7.

- ↑ Source: Geographisches Handbuch zu Andrees Handatlas, vierte Auflage, Bielefeld und Leipzig, Velhagen und Klasing, 1902.

- ↑ Jackson J. Spielvogel: Western Civilization: Alternate Volume: Since 1300. p. 618.

- 1 2 ""Mitteleuropa" is a multi-facetted concept and difficult to handle" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ A. Podraza, Europa Środkowa jako region historyczny, 17th Congress of Polish Historians, Jagiellonian University 2004

- ↑ Joseph Franz Maria Partsch, Clementina Black, Halford John Mackinder, Central Europe, New York 1903

- ↑ F. Naumann, Mitteleuropa, Berlin: Reimer, 1915

- ↑ "Regions and Eastern Europe Regionalism – Central Versus Eastern Europe". Science.jrank.org. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ Marta Petricioli; Donatella Cherubini (2007). For Peace in Europe: Institutions and Civil Society Between the World Wars. Peter Lang. p. 250. ISBN 978-90-5201-364-0. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Between Worlds – The MIT Press". Mitpress.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 22 September 2006. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ , and ; Géographie universelle (1927), edited by Paul Vidal de la Blache and Lucien Gallois

- 1 2 Deak, I. (2006). "The Versailles System and Central Europe". The English Historical Review CXXI (490): 338. doi:10.1093/ehr/cej100.

- 1 2 3 Johnson, p. 165

- ↑ Hayes, p. 16

- ↑ Hayes, p. 17

- ↑ Johnson, p. 6

- 1 2 Johnson, p. 7

- ↑ Johnson, p. 170

- 1 2 Sinnhuber, Karl A. (1954-01-01). "Central Europe: Mitteleuropa: Europe Centrale: An Analysis of a Geographical Term". Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers) (20): 15–39. doi:10.2307/621131. JSTOR 621131.

- ↑ "Kundera's article in PDF format" (PDF).

- ↑ "Central versus Eastern Europe".

- ↑ One of the main representatives was Oscar Halecki and his book The limits and divisions of European history, London and New York 1950

- ↑ A. Podraza, Europa Środkowa jako region historyczny, 17th Congress of Polish Historians, Jagiellonian University 2004

- ↑ Band 16, Bibliographisches Institut Mannheim/Wien/Zürich, Lexikon Verlag 1980

- ↑ Jerzy Kłoczowski, Actualité des grandes traditions de la cohabitation et du dialogue des cultures en Europe du Centre-Est, in: L'héritage historique de la Res Publica de Plusieurs Nations, Lublin 2004, pp. 29–30 ISBN 83-85854-82-7

- ↑ Oskar Halecki, The Limits and Divisions of European History, Sheed & Ward: London and New York 1950, chapter VII

- ↑ Tiersky, p. 472

- 1 2 Katzenstein, p. 6

- ↑ Katzenstein, p. 4

- ↑ Lonnie R. Johnson "Central Europe: enemies, neighbors, friends", Oxford University Press, 1996 ISBN 0-19-538664-7

- 1 2 Johnson, p.4

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Johnson, p. 4

- ↑ Legvold, Robert (May–June 1997). "Central Europe: Enemies, Neighbors, Friends". Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- ↑ "Selected as "Editor's Choice" of the History Book Club". Oxford University Press. Retrieved 20 May 2009.

- ↑ Bucur, Maria (June 1997). "The Myths and Memories We Teach By". Indiana University. HABSBURG. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ "Europe". Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2009.

- ↑ "Slovenia". Encarta. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ↑ "For the Record – The Washington Post – HighBeam Research". Highbeam.com. 3 May 1990. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ "From Visegrad to Mitteleuropa". The Economist. 14 April 2005.

- ↑ Armstrong, Werwick. Anderson, James (2007). "Borders in Central Europe: From Conflict to Cooperation". Geopolitics of European Union Enlargement: The Fortress Empire. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 978-1-134-30132-4.

- ↑ "Map of Europe". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- 1 2 "United Nations Statistics Division- Standard Country and Area Codes Classifications (M49)". Unstats.un.org. 31 October 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- 1 2 "World Population Ageing: 1950-2050" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Browse MT 7206 | EuroVoc". Eurovoc.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ Webra International Kft. (18 March 1999). "The Puzzle of Central Europe". Visegradgroup.eu. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ "Highlights of Eastern Europe (Vienna through Slovenia, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic)". a-ztours.com. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "Mastication Monologues: Western Europe". masticationmonologues.com. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "In the Heavy Shadow of the Ukraine/Russia Crisis, page 10" (PDF). European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. September 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "UNHCR in Central Europe". UNCHR.

- ↑ "Central European Green Corridors - Fast charging cross-border infrastructure for electric vehicles, connecting Austria, Slovakia, Slovenia, Germany and Croatia" (PDF). Central European Green Corridors. October 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02.

- ↑ "Interreg CENTRAL EUROPE Homepage". Interreg CENTRAL EUROPE.

- ↑ Andrew Geddes,Charles Lees,Andrew Taylor : "The European Union and South East Europe: The Dynamics of Europeanization and multilevel goverance", 2013, Routledge

- ↑ Klaus Liebscher, Josef Christl, Peter Mooslechner, Doris Ritzberger-Grünwald : "European Economic Integration and South-East Europe: Challenges and Prospects", 2005, Edward Elgar Publishing Limited

- ↑ Sven Tägil, Regions in Central Europe: The Legacy of History, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1999, p. 191

- 1 2 Klaus Peter Berger, The Creeping Codification of the New Lex Mercatoria, Kluwer Law International, 2010, p. 132

- ↑ "central europe romania - Google Search".

- ↑ United States. Foreign Broadcast Information Service Daily report: East Europe

- ↑ Council of Europe. Parliamentary Assembly. Official Report of Debates. Council of Europe. 1 October 1994. p. 1579. ISBN 978-92-871-2516-3. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ UNDP, About Serbia , UNDP in Serbia, 2013

- ↑ Irena Kogan: Delayed Transition: Education and Labor Market in Serbia , Making the Transition: Education and Labor Market Entry in Central and Eastern Europe, 2011, chapter 6

- ↑ Peter Shadbolt , CNN, Serbia: the country at the crossroads of Europe, 2014

- ↑ WMO, UNCCD, FAO, UNW-DPC , Country Report Drought conditions and management strategies in Serbia, 2013, pg.1

- ↑ Transcarpathia: Perephiral Region at the "Centre of Europe" (Google eBook). Region State and Identity in Central and Eastern Europe (Routledge). 2013. p. 155. ISBN 1136343237.

- ↑ Paul Robert Magocsi (2002). Historical Atlas of Central Europe. University of Toronto Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8020-8486-6. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ Danube Facts and Figures. Bosnia and Herzegovina (April 2007) (PDF file)

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Dinaric Alps (mountains, Europe)". Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ Juliane Dittrich. "Die Alpen – Höhenstufen und Vegetation – Hauptseminararbeit". GRIN. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- ↑ Wolfgang Frey and Rainer Lösch; Lehrbuch der Geobotanik. Pflanze und Vegetation in Raum und Zeit. Elsevier, Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, München 2004 ISBN 3-8274-1193-9

- ↑ Louise Olga Vasvári (2011). Steven Tötösy de Zepetnek, ed. Comparative Hungarian Cultural Studies. Purdue University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-55753-593-1. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ There is no data in the Liechtenstein of economic globalization

- ↑ "Demography report 2010" (PDF). Eurostat. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ↑ Główny Urząd Statystyczny / Spisy Powszechne / NSP 2011 / Wyniki spisu NSP 2011

- ↑ "Czech Republic: The Final Census Results to be Released in the Third Quarter of 2012" (PDF). Czech Statistical Office. 7 May 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ SAJTÓTÁJÉKOZTATÓ 2013 [PRESS CONFERENCE 2013] (PDF) (Press release) (in Hungarian). Hungarian Central Statistical Office. 28 March 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Swiss Statistics - Overview". Bfs.admin.ch. 27 August 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Development in the number of inhabitants - 2011, 2001, 1991, 1980, 1970" (PDF). Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2012.

- ↑ "Central Bureau of Statistics". Dzs.hr. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- ↑ Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia - Population, Slovenia, 1 January 2014 – final data

- ↑ "Landesverwaltung Liechtenstein". Llv.li. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Total population, Candidate countries and potential candidates". Eurostat.

- ↑ "2014 KOF Index of Globalization" (PDF). KOF Index of Globalization. 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "The 2014 Legatum Prosperity Index". Legatum Prosperity Index 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "Corruption Perceptions Index 2014 - Infographics". Cpi.transparency.org. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ "Bribe Payers Index Report 2011". 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-05-02. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Paul Robert Magocsi (2002). Historical Atlas of Central Europe. University of Toronto Press. p. 1758. ISBN 978-0-8020-8486-6. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Launch of railway projects puts Serbia among EU member states". Railway Pro. 27 February 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ "Response to questionnaire for: Assessment of strategic plans and policy measures on Investment and Maintenance in Transport Infrastructure Country: Serbia" (PDF). internationaltransportforum.org. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Inland transport infrastructure at regional level - Statistics Explained". Epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ "Statistical Database - United Nations Economic Commission for Europe". W3.unece.org. 29 December 1980. Archived from the original on 2014-10-22. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ "Spread of the Industrial Revolution". Srufaculty.sru.edu. 16 August 2001. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ Gnel Gabrielyan, Domestic and Export Price Formation of U.S. Hops School of Economic Sciences at Washington State University. PDF file, direct download 220 KB. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ "The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2011: Beyond the Downturn" (PDF). World Economic Forum. 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ Ewing, Jack (2013-12-22). "Midsize Cities in Poland Develop as Service Hubs for Outsourcing Industry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2015-10-06.

- ↑ "2013 Top 100 Outsourcing Destinations: Rankings and Report Overview" (PDF). Tholons. January 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Special Eurobarometer 386: Europeans and Their Languages Report" (PDF). European Commission. June 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Overview | EF Proficiency Index". Ef.co.uk. 2 November 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ↑ Robert Lindsay. "Mutual Intelligibility of Languages in the Slavic Family" (PDF). Last Voices/Son Sesler. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Hungarian language in Europe". Language knowledge. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "PISA 2012 Results in Focus: What 15-year-olds know and what they can do with what they know" (PDF). OECD. 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ Joachim W. Stieber: "Pope Eugenius IV, the Council of Basel and the secular and ecclesiastical authorities in the Empire: the conflict over supreme authority and power in the church", Studies in the history of Christian thought, Vol. 13, Brill, 1978, ISBN 90-04-05240-2, p.82; Gustav Stolper: "German Realities", Read Books, 2007, ISBN 1-4067-0839-9, p. 228; George Henry Danton: "Germany ten years after", Ayer Publishing, 1928, ISBN 0-8369-5693-1, p. 210; Vejas Gabriel Liulevicius: "The German Myth of the East: 1800 to the Present", Oxford Studies in Modern European History Series, Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 0-19-954631-2, p. 109; Levi Seeley: "History of Education", BiblioBazaar, ISBN 1-103-39196-8, p. 141

- ↑ "About the Charles University". Charles University. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "History of Jagiellonian University".

- ↑ "History of the University of Vienna". University of Vienna. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "UP Story - 650 years". University of Pécs. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "About the University". Heidelberg University. 2015-03-23. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ Meuthen, Erich (2015-07-17). "A Brief History of the University of Cologne". University of Cologne. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "About the University of Zadar". University of Zadar. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "Mission Statement of Leipzig University".

- ↑ ""Light of the North" – Between University of the Hansa and Mecklenburg State University". University of Rostock. 2015-01-20. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "University of Greifswald". University of Pécs. 2015-10-19. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "As Important Yesterday as Tomorrow: Intelligent Minds". University of Freiburg. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "About the University". University of Basel. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "About LMU Munich". Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. Retrieved 2015-10-19.

- ↑ "History of the University".

- ↑ Aisha Labi (2 May 2010). "For President of Central European University, All Roads Led to Budapest". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "CEU Facts and Figures". Central European University. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "Central European Exchange Program for University Studies". ceepus.info. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ "CEEPUS Member Countries and NCOs (2008)". ceepus.info. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ↑ Faculty of Arts and Sciences Harvard College. "Central European Studies". Static.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Project MUSE - Comparative Central European Culture". Muse.jhu.edu. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "pError". Go.hrw.com. Retrieved 2015-09-27.

- ↑ "Map: The Religious Divisions of Europe ca. 1555". Pearson. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Map of Europe in 1560: Religion". Emersonkent.com. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Art of cheese-making is 7,500 years old". Nature News & Comment.

- ↑ "CIA Secret Detention and Torture". Open Society Foundations. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "TRANSCEND MEDIA SERVICE". TRANSCEND Media Service. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "In praise of writers' bloc: How the tedium of life under Communism gave rise to a literature alive with surrealism and comedy". The Independent. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Comparative Central European Culture". Thepress.purdue.edu. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Czech mates". Newstatesman.com. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Archived 23 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Secondary Fields". Slavic.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Literatura Środkowoeuropejska w poszukiwaniu tożsamości". Usosweb.uj.edu.pl. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "literalab". literalab. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Regulations". Angelus.com.pl. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Reporters Without Borders".

- ↑ "Central Europe Throwdown 2015". Central Europe Throwdown 2015. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "2018 FIFA World Cup Russia™ - Qualifiers - FIFA.com". FIFA.com. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Germany are FIFA World Cup Champions!". NDTVSports.com. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ James Richardson. "World Cup Football Daily: Germany crowned champions of the world". the Guardian. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Democracy index 2012: Democracy at a standstill: A report from The Economist Intelligence Unit" (PDF). The Economist. 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ↑ "Vision of Humanity".

- ↑ Since Poland was partitioned since 1922 (official adoption), the dates of introduction in Germany (1893) and Austria (1893) should be understood as de facto adoption

- ↑ "Lovejoy - Season 3, Episode 13: The Prague Sun - TV.com". TV.com. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- ↑ Richard Brody (7 March 2014). ""The Grand Budapest Hotel": Wes Anderson’s Artistic Manifesto". The New Yorker. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Los Angeles Times (22 February 2015). "Oscars 2015 live updates: J.K. Simmons, 'Grand Budapest Hotel' win first awards - LA Times". latimes.com. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

Bibliography

- Ádám, Magda (2003). The Versailles System and Central Europe Variorum Collected Studies. ASHGATE. ISBN 0-86078-905-5.

- Ádám, Magda (1993). The Little Entente and Europe(1920-1929). Akadémiai Kiadó. ISBN 963-05-6420-3.

- Ágh, Attila (1998). The politics of Central Europe. SAGE. ISBN 0-7619-5032-X.

- Hayes, Bascom Barry (1994). Bismarck and Mitteleuropa. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3512-4.

- Johnson, Lonnie R. (1996). Central Europe: enemies, neighbors, friends. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510071-6.

- Katzenstein, Peter J. (1997). Mitteleuropa: Between Europe and Germany. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-124-0.

- O. Benson, Forgacs (2002). Between Worlds. A Sourcebook of Central European Avant-Gardes, 1910–1930. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02530-0.

- Tiersky, Ronald (2004). Europe today. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-2805-5.

- Tötösy de Zepetnek, Steven (2002), Comparative Central European culture, Purdue University Press, ISBN 1-55753-240-0

- Shared Pasts in Central and Southeast Europe, 17th-21st Centuries. Eds. G.Demeter, P. Peykovska. 2015

Further reading

- Jacques Rupnik, "In Search of Central Europe: Ten Years Later", in Gardner, Hall, with Schaeffer, Elinore & Kobtzeff, Oleg, (ed.), Central and South-central Europe in Transition, Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000 (translated form French by Oleg Kobtzeff)

- Article 'Mapping Central Europe' in hidden europe, 5, pp. 14–15 (November 2005)

- "Journal of East Central Europe": http://www.ece.ceu.hu

- Central European Political Science Association's journal "Politics in Central Europe": http://www.politicsincentraleurope.eu/

- CEU Political Science Journal (PSJ): http://www.ceu.hu/poliscijournal

- Central European Journal of International and Security Studies: http://www.cejiss.org/

- Central European Political Studies Review: http://www.cepsr.com/

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Middle Europe. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: East/Central Europe |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Central Europe. |

-

The dictionary definition of central europe at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of central europe at Wiktionary - Halecki, Oscar. "BORDERLANDS OF WESTERN CIVILIZATION A History of East Central Europe" (PDF). Oscar Halecki. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- The Centrope region

- Map of Europe

- Maps of Europe and European countries

- CENTRAL EUROPE 2020

- Central Europe Economy

- UNHCR Office for Central Europe

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|