Center Square/Hudson–Park Historic District

|

Center Square/Hudson–Park Historic District | |

| |

|

Row houses on Hamilton Street with Empire State Plaza in background, 2009 | |

| |

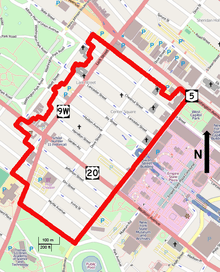

| Location | Roughly bounded by Park Ave., State, Lark and S. Swan Sts., Albany, NY |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°39′8″N 73°45′55″W / 42.65222°N 73.76528°WCoordinates: 42°39′8″N 73°45′55″W / 42.65222°N 73.76528°W |

| Area | 99 acres (40 ha) |

| Built | 1825–1932 |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Mid 19th Century Revival, Late 19th And 20th Century Revivals, Late Victorian |

| NRHP Reference # | 80002578[1] |

| Added to NRHP | March 18, 1980 |

The Center Square/Hudson–Park Historic District is located between Empire State Plaza and Washington Park in Albany, New York, United States. It is a 27-block area taking in both the Center Square and Hudson/Park neighborhoods, and Lark Street on the west. In 1980 it was recognized as a historic district and listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Most of its buildings were constructed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with some dating as far back as the 1830s, in a diverse array of architectural styles of the era. Many prominent architects, including Marcus T. Reynolds and Russell Sturgis, have extant work in the district. Only 22 buildings are more modern, non-contributing properties. While 80% of its buildings are attached rowhouses, giving it a predominantly residential character even today, it also includes churches, two small parks and the Alfred E. Smith State Office Building.[2] Among those are the city's oldest black church and the firehouse that housed its last volunteer fire department. One of Albany's legendary figures, longtime mayor Erastus Corning 2nd, was born in a house on Chestnut Street; another, gangster Legs Diamond, was murdered in one on Dove Street.

Development of the neighborhood began in the 1840s, when the Ruttenkill Creek ravine was filled in. In those early years, houses built there reflected the socioeconomic diversity of the residents. Some were large, high style buildings, the homes of wealthy city residents; others were smaller, more vernacular interpretations built in groups for lower-income buyers. Later, in the last decades of the 19th century, it became a more desirable neighborhood after the current state capitol and Washington Park were built. It continues to remain so, although it did not get its current names until two neighborhood associations were formed to resist urban renewal in the 1960s and '70s.[3]

Geography

The district is a roughly rectangular area with a regular boundary on the east and an irregular one on the west. Center Square, the northern section, is considered to be those six blocks between Lark, State, South Swan and Jay streets.[4] South of that is Hudson–Park.[5]

Its boundary begins at the intersection of Washington Avenue (New York State Route 5) and South Swan Street. On the intersection's southwest corner is the Aflred Smith building, the district's largest, near the New York State Capitol, a National Historic Landmark, and the State Education Department Building, also on the Register. From there the district's eastern boundary runs straight south along South Swan for one-half mile (1 km), past the modern buildings of Empire State Plaza and the New York State Museum, to Park Avenue at the north edge of Lincoln Park.[2]

It continues two blocks west to Delaware Avenue (U.S. Route 9W) where it turns north along that street for one block. Then it turns west at Myrtle Avenue, avoiding a large modern building on the intersection's southwest corner, to follow it west for one block. It then turns north along Lark Street, for two blocks, turning west again at Dana Avenue. After taking in two lots on the north side of the street, it follows the lot lines off the street to the middle of the block, turning west to take in all the buildings on the south side of Madison Avenue (U.S. Route 20) to just opposite the intersection with Willet Street, at the southeast corner of Washington Park.[2]

The buildings on Willet are part of the Washington Park Historic District, so the boundary turns east again, excluding the two lots just east of the intersection. It then follows rear lot lines through the middle of the next three blocks to Spring Street, where it turns east. From there it follows Spring east for a thousand feet (300 m), putting two more Register-listed properties, the Walter Merchant House and Harmanus Bleecker Library, just outside the district, to Dove Street. It continues along the lot lines to the west side of the Smith Building lot, where it turns to Washington to take in that building.[2]

Topographically the district reflects the proximity of the Hudson River a half-mile (1 km) to the east. It generally slopes slightly in that direction. There is a more pronounced dip centered on Hudson Avenue in the eastern (Center Square) portion, where one of the ravines that characterized the area before the city was developed was filled in. A similar depression occurs, for the same reason, in the district's southeast corner next to Lincoln Park.[2]

The 99 acres (40 ha) of the district is urban and densely developed. The majority of buildings are two-to-four-story attached brick rowhouses, or similar detached townhouses, usually three bays built in the late 19th or early 20th centuries, in a range of architectural styles from late Federal to Colonial Revival, high and low. They are often grouped in similar clusters due to simultaneous development, although no one style predominates over a single street or block. There are a few older timber frame houses, mainly in the south end on Myrtle and Park avenues. Many properties have detached garages in the rear, either converted carriage houses or built as garages in the 20th century.[2]

Scattered around the district are other building types, primarily institutional. They range from the 34-story Smith Building at the northeast corner and the brick structures of the former Hinckle Brewery on Park Avenue to the six churches, most notably the Wilborn Temple on Lancaster Street, whose tower is a secondary focal point of the district after the Smith Building. Although most commercial use in the district is of mixed-use character, occurring in the basements and at street level of otherwise residential rowhouses, there are some historic commercial buildings, as well as larger modern, non-contributing development like supermarkets and gas stations.[2]

Formal open space in the district is limited to the small Hudson–Jay Park between those two streets near South Swan and the loop at the aborted stub end of the South Mall Arterial, and the very small Dana Park on Delaware Square where Delaware Avenue and Lark merge at Madison. However, many of the houses in the district have large backyards. Vacant lots, not all of which have been converted into parking lots, also provide breaks in development. Many streets have been lined with mature trees to further provide shade and calm traffic. Some retain their original cobblestone or brick pavement, and crosswalks have been paved that way in other areas.[2]

History

Center Square and Hudson–Park have four distinct historical periods. During the city's colonial period and even after the opening of the Erie Canal, it was little-used and remote from downtown. Development took off after the filling of the Ruttenkill Creek ravine in 1845. By the end of the century the area was one of the city's most prestigious addresses, but change began slowly in the early 20th century, with more non-residential use creeping in.[2] Later in the century, the neighborhood associations formed to preserve the area finally gave their name to both neighborhoods,[6] as well as guiding their development into, once again, an affluent and desirable area of Albany to live in.[7]

1664–1845: Pre-development

For most of the colonial era, Albany had been confined by a defensive wooden stockade to its present downtown. It had come down after British victory in the French and Indian War ended any threat from the French, but the tensions that led to the Revolutionary War a decade later, and its aftermath, had limited the city's growth. The land where the district would later stand was known as Pinkster Hill, since the annual spring festival held by the area's African Americans, both slave and free, was held there until 1822.[7]

Even when the city began to grow again significantly after becoming the eastern terminus of the Erie Canal in 1825, its expansion was primarily north and south along the Hudson River, where the land was level. A few residents ventured to the west. Several houses were built on State and Lydius (today's Madison Avenue) streets during the 1830s. These were generally small timber frame buildings, a few of which remain, mostly small cottages. The 1837 house at 321 State Street is the oldest intact property in the district, and it is predated by the 1827 Alfred Conckling House at 353 Madison Avenue, which had a third story added in the 1920s.[2] In 1842 the Israel African Methodist Episcopal Church, the oldest black church in the city, bought land at its present site at 381 Hamilton Street. It built a church there which burned down two years later.[8]

1845–1899: Growth and development

Just to the west of the city rose sharp bluffs penetrated by ravines that had been carved by the small local tributaries of the Hudson. To better connect the growing city's neighborhoods, they were filled in over time. One such filling, the Ruttenkill Creek, made possible the development of the future historic district in 1845. The new area, between Hawk, State, Lark and Madison, attracted builders very quickly.[2] Fire Station No. 6, home to the city's last company of volunteers, was built at South Swan and Jefferson streets in the 1860s.[9] In 1867 Lydius Street was renamed Madison Avenue after former U.S. President James Madison, a move that was attacked as an effort to further cleanse Albany of its Dutch colonial past.[10] Horsecar service, later replaced by electrified streetcar service, was introduced along a route following Hamilton Street to Lark and then south to Madison Avenue in the 1860s. An 1890s-vintage electric pole for the system, one of two left in the city, is in front of 401 Hamilton.[8]

Builders almost exclusively put up groups of attached brick rowhouses, often demolishing any earlier structures on the property, changing the character of the district. Many were builders or other local businessmen. Their models ranged from simple buildings for working-class families to high-end houses for affluent buyers. Judge William Learned commissioned Russell Sturgis to design homes for his family at 298–300 State Street in 1873, one of only two buildings he designed in the city.[11] Originally architects and builders worked in the Italianate style, but later projects used contemporary styles like the Second Empire and Queen Anne modes.[2]

In the early 1850s the Israel AME Church finally rebuilt, allegedly from a design by its pastor, The Rev. Thomas Jackson. It is the oldest church building in the district.[8] The State Street Presbyterian Church at 260 State Street, today the Westminster Presbyterian Church, was next in 1862, followed by the Emanuel Baptist Church at 275 State seven years later.[12] Other socially prominent residents who moved into the area at that time include Anthony Bleecker Banks, who served as state legislator and mayor,[13] and James Eaton, supervising architect of the new state capitol,[14] who developed many of the homes in the area as well.[2] In 1889 the Richardsonian Romanesque Temple Beth Emeth (today known as the Wilborn Temple, and used as a church), formed from the merger of two synagogues that had once been bitter rivals, was completed at the corner of South Swan and Lancaster.[15] The nearby blocks soon attracted the city's wealthiest Jewish families.[16]

While the rest of the neighborhood grew, the blocks south of Elm Street remained largely undeveloped during this early period. The Hinckel brewery had been located at Park and South Swan since 1855.[17] But for residents, those blocks were too far from downtown Albany and the riverfront to walk to work there, and no streetcar lines reached them. In 1886 the ravine to the south was filled and Lincoln Park created. Development there remained slow, however.[2]

Another park helped transform the district into a more upscale enclave. Over the course of the 1870s and 80s, Washington Park was gradually acquired and developed. The streets around it became the city's newest desirable address, with their wealthy residents building houses larger than the rowhouses they had previously called home. The spillover effect on property values on the streets to the east was enhanced when the new state capitol was just to the east. By 1896, two years before the capitol was complete, every street in the district had at least one address on Albany's Social List.[2]

1900–1956: Consolidation

In the first decades of the 20th century the neighborhood began to change slightly. Large apartment houses were built,[2] such as the buildings at 352 and 355 State Street. The latter, designed by Marcus T. Reynolds, architect of many of the city's prominent buildings from this era, would become popular with the district's longtime residents as they aged.[18] Nine years after its 1915 construction, in one of the city's greatest engineering feats, the Fort Frederick was moved, intact and with furnishings, to its present location at 248 State from Washington and Swan, in order to make way for what was eventually built as the Alfred E. Smith State Office Building.[19] Existing houses were subdivided into apartments as well.[2] In 1913, with Prohibition appearing more and more likely, the former Amsdell Brewery at 175 Jay Street was also converted into apartments.[20] The vacant Albany Card and Paper Company plant at 270–76 Hudson Street was converted into a movie theater in 1916.[21]

This trend toward larger buildings and greater density culminated with the completion of the Smith Building in 1928. The 34-story Art Deco skyscraper instantly became the district's largest building. As subsequent office buildings in the district were not architecturally sympathetic with the rowhouses around them, it is considered the district's youngest contributing property.[2]

Elsewhere in the district during the first three decades of the new century, in 1903 a memorial fountain to geologist James Dwight Dana was erected in the small park now named after him where Lark Street and Delaware Avenue merge at Madison Avenue. Nearby, at 25 Delaware Avenue 14 years later, in 1917, the city's fire department built the Dutch Colonial Revival fire signaling building.[22]

As Prohibition had been anticipated by the conversion of a brewery into apartments, Repeal was heralded one of the most notorious events in the district's history. In the early hours of December 12, 1931, gangster Legs Diamond, who had grown rich partly through sales of illegal liquor, was shot dead in his hideout on the upper floor of 67 Dove Street as he slept off a party the night before. The killing officially remains unsolved.[20]

The Great Depression, which followed, had an effect on the district. Since the 1890s the wealthy families that lived there had often merely rented their rowhouses while owning summer residences outside the city, in then-rural communities like Loudonville, Slingerlands, Altamont or Selkirk. In the 1930s, cash-strapped landlords began pressuring their city tenants to either buy the properties outright or move. With the advent of the automobile, commuting to work in the city from outlying locations had become easier, and many faced with that choice took the latter route, taking up full-time residence in what had up to then been their summer homes, and beginning the suburbanization of the Albany area, a process that accelerated after World War II.[19]

1957–present: Neighborhood associations

In 1957 residents of the six blocks between State, South Swan, Jay and Lark formed the Center Square Neighborhood Association (CSNA), Albany's oldest such organization,[23] which ultimately lent its name to their neighborhood.[6] By the late 1960s it had played a key role in the city's zoning overhaul. In the early 1970s it successfully opposed both a plan to demolish four buildings for a parking garage, and an attempt by McDonald's to open a restaurant in the neighborhood.[24] The later condemnation of the neighborhoods east of South Swan for Empire State Plaza, and the plans to extend the South Mall Arterial freeway west along Jay Street, spurred the creation of the Hudson/Park Neighborhood Association in the 1970s. It succeeded both in stopping the highway project, and giving a name to its neighborhood.[6]

As it had been when the area was first developed, Center Square and Hudson/Park were socioeconomically diverse at the time the neighborhood associations were established. Over the course of the 1980s, that changed in Center Square as the CSNA's success began to make that neighborhood a desirable place for the young professionals of the era to live. By 1990 it had the highest rents in the city.[25] The CSNA helped residents fight the city over a property tax reassessment in the late 1980s that many of them believed had singled out their neighborhood.[26] It also successfully opposed another parking garage proposal at that time.[25]

The neighborhood association's success in getting its way with city politicians has been attributed to its membership having many lawyers, civil servants and other well-connected present and former residents to draw upon.[27] It has sometimes drawn criticism as an elite group that represents the interests of only its members in preserving the neighborhood's high property values at the expense of the city as a whole.[28] Specifically, when organized opposition by the CSNA and other groups in the city prevented the construction of another proposed parking garage in the late 1980s, some residents of adjacent blocks complained that they had been open to the plan as long as it could be amended to show more sensitivity to the historic character of the neighborhood. They pointed out that residents often competed for parking with state workers in the buildings at Empire State Plaza, and that older residents and those with small children had considered moving out of the neighborhood for the suburbs due to the parking problem.[26] Others have complained that the CSNA's opposition to sidewalk cafes near residences, and some art galleries on the Lark Street end of the neighborhood, restricts the area's growth by keeping out businesses essential to a desirable urban setting.[29]

Historic preservation of the neighborhoods led the producers of the film adaptation of William Kennedy's novel Ironweed to use Lark Street as a location. The story takes place in Albany during the Depression, and it did not need to be recreated as many buildings from that era still stood. "The trolley came back to Lark Street in Albany," recalled Kennedy, "on a block where it had never run."[30]

In the 1990s the CSNA and the Lark Street Merchants Association began working together in response to early signs of urban decay brought on by that era's recession. They formed the Lark Street Revitalization Committee and were able to secure approximately half a million dollars in grants to restore and redevelop the area.[28] Eventually they formed a business improvement district. Lark Street has since become regionally noted for its arts community. It hosts several annual festivals, including Art on Lark, Winter WonderLark, its Champagne on the Park annual fundraiser and LarkFEST, the state's largest single-day open-air street festival.[31]

Since at least the 1970s the city's gay community had been centered on Lark Street.[32] As gay visibility increased in the 1990s, Lark became identified as Albany's gay village. The Pride Center of the Capital Region has its office on Hudson near Lark.[33] The city's annual gay pride parade is held along State[34] and Lark,[35] ending in a festival at Washington Park.[36]

Significant contributing properties

While no building in the district is currently listed individually on the National Register, many of its contributing properties are noteworthy within its context.

Properties known by their address

These were all built as single-family residences, although their use may changed over the years.

- 67 Dove Street: Early one morning in December 1931, gangster Legs Diamond was hiding out on the second floor of this two-story 1850s brick townhouse, sleeping off a party after a recent trial in Troy. Someone came in, went upstairs and shot him to death. The crime remains officially unsolved.[20]

- 142 Chestnut Street: Built in 1875 as a stable for Brides Row builder John Myers, who lived nearby on Lancaster Street, this two-story brick structure was converted into a house in 1913. At that time a square bay was added in the middle of the second story; the rebuilt area is faced in stucco.[37]

- 148 Lancaster Street: This five-bay Italianate brick building with a brownstone-trimmed entryway is the largest house on its block. It was built around 1876 for Charles Knowles, a local insurance agent.[16]

- 162–170 Jay Street: This brick Italianate row was built as speculative housing by bank president Thomas W. Olcott and lawyer James King in 1875.[20]

- 182–216 Elm Street: These 18 brick Italianate houses are the longest row in the district. Developer George Martin built them in 1871 and sold them to both new residents looking to live in the neighborhood and longtime residents looking for smaller houses.[9]

- 187 Lancaster Street: Thomas Ward, a printer at the Albany Argus newspaper, commissioned this two-story brick house in 1872. It was likely one of the first of many in the city built by William Sayles. The symbols inside the circles on the cornice and elsewhere on the facade reportedly represent the Isle of Man, where Ward was born.[38]

- 188 Lancaster Street: Built in 1876 by a local mason, this ornate brick Italianate house has eyebrow windows in its attic story.[38]

- 204–220 Lancaster Street: James Eaton, supervising architect of the state capitol, built this Richardsonian Romanesque row of rusticated brownstones in the late 1880s. One of his last projects in the neighborhood, the stone used was reportedly that salvaged from the former state capitol building after it was demolished in 1883.[39]

- 209 Lancaster Street: Originally built around 1863, this ornate brick structure was remodeled into a double house with a projecting bay over the front door a decade later. Alexander Selkirk, architect of several houses in the district and buildings elsewhere in the city, lived here early in the 20th century.[39]

- 261 State Street: Architect Alexander Selkirk designed this 1897 Roman brick townhouse for a physician. The south and west transoms have stained glass and there are lions' heads in the copper cornice.[19]

- 274 State Street: Merchant Luther Palmer built this house for his family in 1873. A 1920s owner redid the interior in Japanese style.[40]

- 278 State Street: This 1847 house built by a cattle merchant is one of the oldest on the block. The rope pattern on the door surround was a common decorative touch at that time.[40]

- 281 State Street: When built in 1881, this house of brownstone and pressed brick was one of Albert Fuller's first projects in Albany. Unlike most of his other work from that time, it makes heavy use of Classical detailing, such as scrolled pediments, a swag and rosettes.[40]

- 284 State Street: This five-bay brownstone with a recessed doorway and drip moldings was built around 1860 for a local bank president. Its cast iron railings have balusters and newel posts designed to look like carved stone.[40]

- 292–294 State Street: Among the oldest in the entire district, these were built around 1846 for two local plumbers. Both have since been upgraded slightly. A Queen Anne Style shingled bay window was added to 292 in the 1880s, but it is otherwise as it was when originally built.[40] In 1899, Marcus T. Reynolds renovated 294 extensively for a college classmate, moving the entrance to Dove Street and replacing the original stoop with a bay window featuring a scrolled pediment and tapered pilasters. The owner, Gerrit Lansing, had the seal of the Dutch East India Company worked into the bay window's stained glass to reflect his descent from the city's early settlers. In the 1920s, the house was home to the Candlelight Tea Room, a popular restaurant of the time.[11]

- 293–329 Hudson Avenue: One of the longest rows of speculative housing in the district, these eight two-story two-bay restrained brick Italianate houses were built by local firm John Kennedy and Son for lawyer Charles Lansing in the 1850s.[21]

- 298 Hudson Avenue: One of the few gabled frame houses in the district, this features a storefront. It was built in 1848, one of the last built before that year's fire led to a ban on new wooden buildings in the city.[21]

- 298–300 State Street: Russell Sturgis designed this large brick Ruskin Gothic home for Judge William Learned in 1873. Its pointed tower with its Moorish window arches dominates the Dove Street intersection. Stone string courses mark off the stories; other decoration includes shingled bays on the Dove facade and corbeled cornices. Polished granite columns support the gabled porch. German painter Emanuel Mickel did the interior murals.[11]

- 306–308 State Street: These 1875 rowhouses, built for the Vandenberg and Ten Eyck families respectively, feature encaustic tile and truncated granite columns in their decoration.[41]

- 312 State Street: This 1870s brownstone features an unusual porch with a wrought iron railing showing sweeping scrolls and flowers. Its front surround has an arched doorway surround with vermiculated quoins. The tiled roof and gabled dormer window may have been added a decade after construction.[41]

- 315 State Street: Built in 1914, this dark red brick Neoclassical house has an unusual vaulted doorway and volutes on its central second-story bay. It was originally home to another member of the Ten Eyck family, a lawyer who lived here during World War I shortly after it was built. It was later owned by several other local businessmen, eventually becoming the property of Nelson Rockefeller. He donated it to the New York State Republican Committee,[41] and it remains their offices.[42]

- 317 State Street: Morris Ryder, a major developer of the district, built this home in 1898 and lived in it for the last two decades of his life. Its front facade, of yellow Roman brick trimmed with brownstone, is topped by a steeply pitched pantile roof with scrolled gable. They and the iron anchor beams were meant to recall the Dutch Colonial past, the remnants of which had been mostly eliminated by that time, to residents' regret.[13]

- 319 State Street: The unrestrained Dutch touches of Ryder's house are balanced by this 1904 Colonial Revival facade designed by Marcus Reynolds during a renovation. It consists of brick laid in Flemish bond on the upper three stories above smooth stone at street level, with large swags on either side of the centrally located main entrance. The second floor has balconies with iron railings in a bellflower pattern, in contrast to a tall iron front fence with spears and tassels.[13]

- 321 State Street: Wedged in between two larger neighbors is the oldest house in the district. This two-and-a-half-story side-gabled timber frame house with gabled dormers and shutters was built for cabinetmaker John Metz around 1840. It is the only one remaining in the vicinity of what were once many other cottage-style houses from the same era.[13]

- 329 State Street: Two-time mayor Anthony Bleecker Banks commissioned this Romanesque Revival double house for his daughter and son-in-law in 1889. Since he owned an earlier 1870 row on the property, the construction work may have been as much renovation as new. The four-bay front facade, of rusticated brownstone, alternates between one that projects, topped by a gable with "CB" in it, and one that recesses. Two wrought iron balconies are located in the recessed bays on the second story.[13]

- 333 State Street: This brownstone with an intricate facade was built over an earlier home in 1888. The intricate stonework, with foliate and geometric designs, was probably done by stonecarvers working on the state capitol at the same time, since builder Scott Dumont Goodwin was friends with state capitol architect Isaac Perry. Each story has a distinct window treatment, from bowed triple windows on the first two floors with arched ones on the third.[13]

- 334–336 State Street: Dating to 1831, these two timber frame houses are the oldest structures on State. Italianate cornices were added in the 1850s.[14]

- 341 State Street: In 1896, Albert Fuller renovated this two-story yellow brick house into contemporary styles. However, he kept the Greek Revival features from the earlier house, such as the intricate ironwork on the stoop railings and the doorway, and added fretwork and dentils on the second-story bay window.[14]

- 342–44 State Street: State capitol supervising architect James Eaton built these two when he was living in the area during the construction of that building in the 1870s. They both have granite trim similar to the capitol and Egyptian-influenced columns similar to those on 298 State Street.[14]

- 343–351 State Street: These four 1890s rowhouses are attributed to Fuller. They feature extensive experimentation in the brickwork patterns on the facade, typical of the era.[14]

- 347–349 Hudson Avenue: The front facade of these two 1851 houses have latticework wooden porches, much like the houses on Hall Place in the Ten Broeck Triangle. They reflect the influence of Andrew Jackson Downing at the time.[21]

- 352 and 355 State Street: The 1905 construction of these two apartment houses, almost facing each other, signaled the beginning of a change to that type of housing not just in the district but the city as a whole. Morris Ryder built both; Marcus Reynolds is known to have designed at least 355. Currently called Capital Hill Apartments, 352 is a six-story structure on the site of a former malthouse, the last remaining large industrial facility in the Center Square area. It has a high granite foundation, carved stone entrance surround, bay windows on the State Street side and French windows with balconies on the Lark facade. Across the street, Reynolds' original seven-story palazzo-style building was scaled down to this four-story brick Baroque Revival building, a popular place for many of the neighborhood's elderly to spend their later years.[14]

- 353 Madison Avenue: This four-bay three-story house is the oldest structure in the district, built for federal Judge Alfred Conkling in 1827. A third story was added in the 1920s.[10]

Properties known by their names

- Alfred E. Smith State Office Building, 80 South Swan Street. One of the district's youngest contributing properties and the second tallest building in Albany at 387 feet (118 m) is located in the eastern corner of the district. The 34-story granite Art Deco skeyscraper, named for Alfred E. Smith, governor during much of its construction, was started in 1915 and finished in 1928.[2]

- Brides' Row, 144–170 Chestnut Street. These 12 yellow brick houses, one of the longest rows in the Center Square portion of the district, were built in 1899. Originally called Myers' Row or even Poverty Row, they soon got the name that persists from the newlywed couples they were sold to. Each has sandstone trim and second story bay windows. Erastus Corning 2nd, mayor of Albany for a 40-year period in the 20th century, was born at 156 Chestnut in 1909.[37]

- Central Fire Alarm Signaling Station, 25 Delaware Avenue. Morris Ryder built this Dutch Colonial Revival brick house in 1917 for the fire department, ending its 23-year quest for a new central signaling location in a fireproof building at an isolated location to replace the one at headquarters damaged in an 1894 fire. Its stepped gable recalls Hook and Ladder No. 4, built a few years further south on Delaware. It continued in its original use until the 1960s. In 1976 a modern wing was attached to it to create the Louise Corning Senior Citizens Center.[22]

- James Dwight Dana Memorial Fountain, Delaware Square. In 1903 members of the Dana Natural History Society, the oldest women's science organization in the country, had this granite memorial erected to recognize the scientific accomplishments of James Dwight Dana, who had died eight years prior. He is believed to have been the first geologist and preceded Charles Darwin in proposing a theory of evolution. The society raised the money itself and ensured that the trilobites, crinoids, and eurypterids depicted on the water basin, which also served as Albany's last public horse trough, were accurately depicted.[22]

- Eighth Tabernacle Temple Beth El, 151 Jay Street. When built in 1873, this brick Italianate structure was the Holland Reformed Church. A sympathetic residence was attached to it in the 1880s. It was acquired by the Italian Christian Church in 1946, and by 1993 it was the Eighth Tabernacle of the Church of God and Saints of Christ.[20]

- Emanuel Baptist Church, 275 State Street. This rusticated limestone structure was the Baptists' response to Westminster Presbyterian, across the street. The main church was finished in 1871, with the tower added 12 years later as a memorial to deacon Eli Perry, a three-term mayor. It is one of the few surviving works by partners William Woollett and Edward Ogden. The interior has a marble baptistery; the pulpit can be lowered to allow an unobstructed view of the baptism. It was redecorated and reroofed in 1928. The original stained glass was replaced in the 18960s.[12]

- Fire Station No. 6, 125 Jefferson Street. Built in 1860, it was home to Americus Engine Co. No. 13, Albany's last volunteer fire department. After 1869 it was home to Steamer No. 6, later Engine 6. In 1938 the Works Progress Administration rebuilt the exterior. It has been closed since 1986; the roof partially collapsed in 2011 from heavy rains brought by Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee.[43] There are plans to repair and redevelop it.[44]

- Fort Federick Apartments, 248 State Street. This eight-story brick structure with stone-faced bay windows on either side was originally located at the corner of Washington Avenue and South Swan in 1915. Nine years later, the Smith Building was due to be built on the site. Instead of demolishing the building, a Pittsburgh-based engineering firm put the entire building on jacks, lifted it up two feet (50 cm) and put it on railroad tracks. Two teams of horses hauled it 350 feet (110 m) to its current location. All the furnishings remained inside and intact; no glass was broken. The only negative effect was that the building's original main entrance now faces an alley on the east.[19]

- Hinckel Brewery Complex, Park Avenue and South Swan Street. Frederick Hinckel started the brewery in 1855 on this site. This five-building complex, the last large industrial facility left in the district, was built following his death in 1881. Beer production continued until 1922; some of the remaining buildings have since been converted to apartments.[17]

- Hudson Theater Apartments, 270 Hudson Street. This five-story, nine-bay brick building was built as a warehouse in 1872. It is the only remnant of the Albany Card and Paper Company complex that occupied this portion of the block between Hudson and Hamilton. In the 1890s some production work was done here as well. A toy company bought the building and, from 1916 to 1932, showed silent movies in a domed arena where the building's central courtyard is now. In 1984 the long-vacant structure was gutted and converted to its current use.[21]

- Israel African Methodist Episcopal Church, 381 Hamilton Street. Albany's first black church was founded in the 1820s, and bought this land in 1842. Their first church burned down two years later, and in 1854 they built the current structure from a design by the pastor, The Rev. Thomas Jackson. The interior was remodeled in the 1880s, and at some point later during many renovations to the exterior the steeple was removed. In 1952 the entire building was refaced in synthetic stone.[8]

- Knickerbocker Apartments, 175 Jay Street. Two breweries originally occupied the site this four-story structure in the 1850s when it was built. Within two decades one, Amsdell Brothers, had taken over the other and used the entire southeast corner of this block. A local real estate agent, sensing that Prohibition was inevitable, bought the building in 1913 and converted it into its present residential use.[20] Complaints about the tenants led it to be referred to as "the neighborhood eyesore" in the 1990s.[45]

- Trinity United Methodist Church, Lark and Lancaster streets. A 1932 fire destroyed the church that replaced one on this site after a 1901 fire. The church responded later that year by building one of the largest religious building complexes in the city. Philadelphia architects Sunndt and Wenner designed this large limestone building with Neo-Gothic and Art Deco aspects. The main entrance is on Lancaster to avoid the busier Lark Street. Its south aisle has stained glass depicting scenes from church history, starting with St. Paul and ending with "the modern student", one receiving a diploma and the other wearing football equipment. Elsewhere on the property is a chapel and parish house, the latter incorporating parts of a 1926 building that survived the 1932 fire.[39]

- Trolley-wire Tower, in front of 401 Hamilton Street. This narrow latticework iron structure, built in the 1890s is one of the only two remaining in the city. It supported the overhead wire for the trolley line that went from downtown to Washington Park and west. That service was discontinued in 1946.[8]

- Welcome Chapel Missionary Baptist Church, 124 Chestnut Street. This site has been in use for religious purposes by both black and white congregations since at least 1876, when an atlas indicated there was a "colored Baptist church" there. A white congregation, the Second Congregational Christian Church, built the current Romanesque Revival building, with a low crenellated tower, is of pressed brick with sandstone trim. It is unclear whether any aspects of the original building survive in the present one. After that congregation merged with one on Quail Street and moved to its building, the Welcome Chapel purchased this one in 1958.[37]

- Westminster Church Education Building, 85 Chestnut Street. This three-story brick structure was built in 1928 after the fire that severely damaged the interior of the Westminster Presbyterian Church a block away. At the time the church owned all the land between both buildings. It is used as a parish hall.[15]

- Westminster Presbyterian Church, 260 State Street. Built in 1862 as the State Street Presbyterian Church, this is one of the district's most significant buildings. It was designed either by William Hodgins or Nichols and Brown. It was one of the first building projects for mason James Eaton, who would later become supervising architect of the new state capitol and a major developer of the future district. In 1919 it was renamed following a merger with the Second Street Presbyterian Church. Nine years later, in 1928, a fire started accidentally during roof repairs ravaged the interior. The original bell and baptismal font survived; the carved reredos and stained glass were added during the repairs.[12]

- Wilborn Temple, South Swan and Lancaster streets. When built in 1885, this stone Richardsonian Romanesque house of worship was Temple Beth Emeth, the home of two Jewish congregations that had been bitter enemies over doctrinal issues when founded in the mid-19th century. State architect Isaac Perry collaborated with a congregant, Adolph Fleischmann, on a design that echoed Albany's city hall, then newly built, in its rustication, hipped roof, massing around a corner tower and arched entryway with an inscription in English and Hebrew. Jews, who had helped develop the surrounding blocks by moving to them in the years after the temple was built, later moved to the suburbs like other city residents, and in 1957 a new temple was built on Academy Road with the original stained glass. The temple building was sold to a Christian church and became Wilborn Temple First Church of God in Christ.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Staff (2009-03-13). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 T. Robins Brown and E. Spencer-Ralph (1976). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Center Square/Hudson-Park Historic District". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2010-10-18. See also: "Accompanying 49 photos".

- ↑ Gilder, Cornelia Brooke (1993). Diana Waite, ed. Albany Architecture: A Guide to the City. Albany, NY: Mount Ida Press. p. 125. ISBN 9780962536816.

- ↑ "HomePage". Center Square Neighborhood Association. May 18, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ↑ "About Us". Hudson/Park Neighborhood Association. 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Gilder, 125.

- 1 2 Rabrenovic, Gordana (1996). Community Builders: A Tale of Neighborhood Mobilization in Two Cities. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 9781566394109. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gilder, 144.

- 1 2 Gilder, 145.

- 1 2 Gilder, 146.

- 1 2 3 Gilder, 129.

- 1 2 3 4 Gilder, 127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gilder, 131.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gilder, 132–33.

- 1 2 Gilder, 135.

- 1 2 Gilder, 136.

- 1 2 Gilder, 150.

- ↑ Gilder, 133.

- 1 2 3 4 Gilder, 126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gilder, 140.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gilder, 141.

- 1 2 3 Gilder, 149.

- ↑ "Lark Street BID". Lark Street Business Improvement District. 2009. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ↑ Rabrenovic, 65

- 1 2 Rabrenovic, 66

- 1 2 Rabrenovic, 81

- ↑ Rabrenovic, 72–73

- 1 2 Rabrenovic, 91

- ↑ Rabrenovic, 78

- ↑ McGilligan, Patrick (1995). Jack's Life: A Biography of Jack Nicholson. W.W. Norton & Co. p. 356. ISBN 9780393313789.

- ↑ "Mission". Lark Street BID. 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ↑ Casidy, Edward F. (2011). Looking Back on Tomorrow: A Life Story. AuthorHouse. pp. 166–67. ISBN 9781467054454.

- ↑ "Our Mission". Pride Center of the Capital Region. 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ↑ "2012 Capital Pride Parade and Festival". Times Union. June 10, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ↑ "2012 Capital Pride Parade and Festival". Times Union. June 10, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Capital Pride 2012 Events". Pride Center of the Capital Region. 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Gilder, 134.

- 1 2 Gilder, 137.

- 1 2 3 Gilder 138.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gilder, 128.

- 1 2 3 Gilder, 130.

- ↑ "Home". New York State Republican Committee. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- ↑ Carleo-Evangelist, Jordan (September 8, 2011). "Ex-firehouse likely damaged by rains". Times Union. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ Carleo-Evangelist, Jordan (October 25, 2011). "New owner, new vision for troubled firehouse". Times Union. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ Rabrenovic, 88

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Center Square/Hudson–Park Historic District. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||