Pan-Celticism

Pan-Celticism is the name given to various political and cultural movements and organisations that promote greater contact between the Celtic nations,[1] as defined by these organizations.

The term 'Celts'

There is some controversy surrounding the term Celts. One such example was the Celtic league's Galician crisis.[1] This was a debate over whether the Spanish region of Galicia should be admitted. The application was rejected on the basis of language.[1]

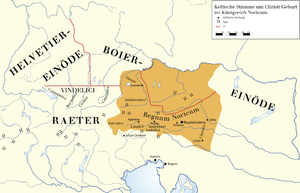

Some Austrians claim that they have a Celtic heritage that became Romanized under Roman rule and later Germanized after Germanic invasions.[2] Austria is the location of the first characteristically Celtic culture to exist.[2] After the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in 1938, in October 1940 a writer from the Irish Press interviewed Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger who spoke of Celtic heritage of Austrians, saying "I believe there is a deeper connection between us Austrians and the Celts. Names of places in the Austrian Alps are said to be of Celtic origin.".[3] Contemporary Austrians express pride in having Celtic heritage and Austria possesses one of the largest collections of Celtic artefacts in Europe[4]

Organisations such as the Celtic Congress and the Celtic League use the definition that a 'Celtic nation' is a nation with recent history of a traditional Celtic language.[1]

Types of Pan-Celticism

Pan-Celticism can operate on one or all of the following levels listed below:

Linguistics

Linguistic organisations promote linguistic ties, notably the Gorsedd in Wales, Cornwall and Brittany, and the Irish government-sponsored Columba Initiative between Ireland and Scotland. Often, there is a split here between the Irish, Scots and Manx, who use Q-Celtic Goidelic languages, and the Welsh, Cornish and Bretons, who speak P-Celtic Brythonic languages.

Music

Music is a notable aspect of Celtic cultural links. Inter-Celtic festivals have been gaining popularity, and some of the most notable include those at Lorient, Killarney, Kilkenny, Letterkenny and Celtic Connections in Glasgow.[5][6]

Sports

Sporting contact is much less common, although Ireland and Scotland play each other at hurling/shinty internationals.[7] There is also the Celtic league involving Rugby union teams from Ireland, Wales and Scotland.[8]

Political

Political groups such as the Celtic League, along with Plaid Cymru and the Scottish National Party have co-operated at some levels in the Parliament of the United Kingdom, and Plaid Cymru has asked questions in Parliament about Cornwall and cooperates with Mebyon Kernow. The Regional Council of Brittany, the governing body of the Region of Brittany, has developed formal cultural links with the Welsh Senedd and there are fact-finding missions. Political pan-Celticism can be taken to include everything from a full federation of independent Celtic states, to occasional political visits. During the Troubles, the Provisional IRA adopted a policy of not mounting attacks in Scotland and Wales, as they viewed England (having been the nation which initially invaded Ireland) alone as the colonial force occupying Ireland. This was also possibly influenced by the IRA chief of staff Seán Mac Stíofáin (John Stephenson), a London-born Englishman who identified as a "Pan-Celt".[9]

Town twinnings

Town twinning is common between Wales – Brittany and Ireland – Brittany, covering hundreds of communities, with exchanges of local politicians, choirs, dancers and school groups.[10]

History of Pan-Celt relations

The kingdom of Dál Riata was a Gaelic overkingdom on the western seaboard of Scotland with some territory on the northern coasts of Ireland. In the late 6th and early 7th century it encompassed roughly what is now Argyll and Bute and Lochaber in Scotland and also County Antrim in Northern Ireland.[11]

As recently as the 13th century, "members of the Scottish elite were still proud to proclaim their Gaelic-Irish origins and identified Ireland as the homeland of the Scots."[12] The 14th century Scottish King Robert the Bruce asserted a common identity for Ireland and Scotland.[12] However, in later medieval times, Irish and Scottish interests diverged for a number of reasons, and the two peoples grew estranged.[13] The conversion of the Scots to Protestantism was one factor.[13] The stronger political position of Scotland in relation to England was another.[13] The disparate economic fortunes of the two was a third reason; by the 1840s Scotland was one of the richest areas in the world and Ireland one of the poorest.[13]

Over the centuries there continued to be considerable contact between Ireland and Scotland, first as Scots Protestants were transplanted into Ulster in the 17th century and then as Irish began to move to Scottish cities in the 19th century. Recently the field of Irish-Scottish studies has developed considerably, with the Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative (ISAI) founded in 1995. To date, three international conferences have been held in Ireland and Scotland, in 1997, 2000 and 2002.[14]

Organisations

- The International Celtic Congress is a non-political cultural organisation that promotes the Celtic language in the six nations of Ireland, Scotland, Brittany, Ireland, Isle of Man and Cornwall.

- The Celtic League, is a Pan-Celtic political organization.

Celtic regions/countries

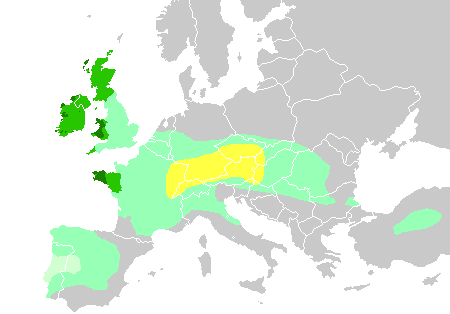

A number of Europeans from the central and western regions of the continent have some Celtic ancestry. As such it is generally claimed that the 'litmus test' of Celticism is a surviving Celtic language [1] and it was on this criterion that the Celtic league rejected Galicia. The following regions have a surviving Celtic language and it on this criterion that they are considered, by The Pan Celtic Congress in 1904 and Celtic League, to be the Celtic nations.[1][15]

Other regions with Celtic heritage are:

- Asturias[1] (with Miranda do Douro, north of Palencia and including parts of León, Zamora, Cantabria [16] [17])

- Austria[2]

- England[18]

- Galicia[1] (with North Portugal[16]) – together as Gallaecia.

Celts outside Europe

Areas with a Celtic language speaking population

In the Americas there are notable Irish and Scottish Gaelic speaking enclaves in Atlantic Canada.[19]

The Patagonia region of Argentina has a sizeable Welsh speaking population. The Welsh settlement in Argentina started in 1865 and is known as Y Wladfa.

The Celtic diaspora

The Celtic diaspora in the Americas, as well as New Zealand and Australia, is significant and organised enough that there are numerous organisations, cultural festivals and university-level language classes available in major cities throughout these regions.[20] In the United States, Celtic Family Magazine is a nationally distributed publication providing news, art, and history on Celtic people and their descendants.[21]

The Irish Gaelic games of Gaelic football and hurling are played across the world and are organised by the Gaelic Athletic Association while the Scottish game shinty has seen recent growth in the USA[22]

Timeline of Pan-Celticism

J.T. Koch observes that modern Pan-Celticism arose in he contest of European romantic pan-nationalism, and like other pan-nationist movements, "flourished mainly before the First World War.[23] He sees twentieth century efforts in this regard as possibly arising out of a post-modern search for identity in the face of increased industrialization, urbanization and technology.

- 1820: The Royal Celtic Society founded in Scotland[24]

- 1838: First Celtic Congress called Pan-Celtic Congress, Abergavenny[25]

- 1867: Second Celtic Congress, Saint-Brieuc[26]

- 1888: Pan-Celtic Society formed in Dublin[27]

- 1891:Pan-Celtic Society disbands[27]

- 1919–1922: Irish War of Independence, five-sixths of Ireland becomes independent, Northern Ireland gets devolved government

- 1939–1945: Second World War and German occupation of Brittany

- 1947: Celtic Union formed[28]

- 1950: Collapse of Celtic Union.[28]

- 1950: Cornwall hosts its first Celtic congress[29]

- 1961: Modern Celtic League founded at Rhosllanerchrugog[30]

- 1971: Killarney Pan Celtic Festival begins[31]

- 1997: Columba Initiative begins[32]

- 1999: Scottish Parliament[33] and Welsh Assembly[34] open

- 2000: The Cornish Constitutional Convention is formed[35]

- 2000–2001:The Cornish Constitutional Convention collect over 50,000 signatures endorsing the call for a Cornish Assembly.[35]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ellis, Peter Berresford. Celtic dawn: the dream of Celtic unity. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- 1 2 3 Carl Waldman, Catherine Mason. Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing, 2006. P. 42.

- ↑ Walter J. Moore. Schrödinger: Life and Thought. Cambridge, England, UK: Press Syndicate of Cambridge University Press, 1989. p.373.

- ↑ Kevin Duffy. Who Were the Celts? Barnes & Noble Publishing, 1996. P. 20.

- ↑ "ALTERNATIVE MUSIC PRESS-Celtic music for a "New World Paradigm"". Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ↑ "Scottish Music Festivals-Great Gatherings of Artists". Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ↑ BBC report

- ↑ "Y Gynghrair Geltaidd". BBC Chwaraeon (in Welsh). British Broadcasting Corporation. 28 September 2005. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- ↑ Pittock, Murray. Celtic Identity and the British Image. Manchester University Press, 1999. p. 111

- ↑ "Home page of Cardiff Council – Cardiff's twin cities". Cardiff Council. 15 June 2010. Retrieved 10 August 2010.

- ↑ Oxford Companion to Scottish History p. 161 162, edited by Michael Lynch, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923482-0.

- 1 2 "Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." by T.M. Devine. Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen. in Radharc: A Journal of Irish Studies Vol 3: 2002 pg 4. The article in turn cites "Myth and Identity in Early Medieval Scotland" by E.J. Cowan, Scottish Historical Review, xxii (1984) pgs 111–135.

- 1 2 3 4 "Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." by T.M. Devine. Research Institute of Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen. in Radharc: A Journal of Irish Studies Vol 3: 2002 pgs 4–8

- ↑ Devine, T.M. "Making the Caledonian Connection: The Development of Irish and Scottish Studies." Radharc Journal of Irish Studies. New York. Vol 3, 2002.

- ↑ Celtic League Homepage

- 1 2 "National Geographic map of celtic regions". Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ "Map of Asturias". Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ↑ "We're nearly all Celts under the skin", "The Scotsman", 21 September 2006.

- ↑ O Broin, Brian. "An Analysis of the Irish-Speaking Communities of North America: Who are they, what are their opinions, and what are their needs?". Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ "Modern Irish Linguistics". University of Sydney.

- ↑ "The Welsh in America". Wales Arts Review. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- ↑ "Thursday's Scottish gossip". BBC News. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2010.

- ↑ Koch, John T., Celtic Culture, ABC-CLIO, 2006, ISBN 9781851094400

- ↑ "The Royal Celtic Society". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "Celtic Congresses in other countries". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "The International Celtic Congress Resolutions and Themes". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- 1 2 "The Pan-Celtic Society" 81. JSTOR 20516479.

- 1 2 "The Capital Scot". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "A short history of the Celtic Congress". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "Rhosllanerchrugog". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "Welcome to the 2010 Pan Celtic Festival". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "Columba Initiative". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ "Scottish Parliament". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

- ↑ and Welsh Assembly.aspx "Queen and Welsh Assembly" Check

|url= - 1 2 "Campaign for a Cornish assembly". Retrieved 5 February 2010.

External links

- The Celtic League

- Celtic Congress

- Map of Celtic Nations

- Columba Initiative

- The Celtic Realm

- Campaign for a Cornish Assembly

- Proposal for a Celtic Confederation

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||