Cecil Rhodes

| The Right Honourable Cecil Rhodes DCL | |

|---|---|

Rhodes, c. 1900 | |

| 7th Prime Minister of the Cape Colony | |

|

In office 17 July 1890 – 12 January 1896 | |

| Monarch | Queen Victoria |

| Governor |

Henry Loch William Gordon Cameron Hercules Robinson |

| Preceded by | John Gordon Sprigg |

| Succeeded by | John Gordon Sprigg |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Cecil John Rhodes 5 July 1853 Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, England, UK |

| Died |

26 March 1902 (aged 48) Muizenberg, Cape Colony (now South Africa) |

| Resting place |

World's View, Matopos Hills, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) 20°25′S 28°28′E / 20.417°S 28.467°E |

| Nationality | British |

| Relations |

Reverend Francis William Rhodes (Father) Louisa Peacock Rhodes (Mother) Francis William Rhodes (Brother) |

| Alma mater | Oriel College, Oxford |

| Occupation |

Businessman Politician |

Cecil John Rhodes PC (5 July 1853 – 26 March 1902)[1] was a British businessman, mining magnate and politician in South Africa, who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. An ardent believer in British imperialism, Rhodes and his British South Africa Company founded the southern African territory of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia), which the company named after him in 1895. South Africa's Rhodes University is also named after him. Rhodes set up the provisions of the Rhodes Scholarship, which is funded by his estate, and put much effort towards his vision of a Cape to Cairo Railway through British territory.

The son of a vicar, Rhodes grew up in Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, and was a sickly child. He was sent to South Africa by his family when he was 17 years old in the hope that the climate might improve his health. He entered the diamond trade at Kimberley in 1871, when he was 18, and over the next two decades gained near-complete domination of the world diamond market. His De Beers diamond company, formed in 1888, retains its prominence into the 21st century. Rhodes entered the Сape Parliament in 1880, and a decade later became Prime Minister. After overseeing the formation of Rhodesia during the early 1890s, he was forced to resign as Prime Minister in 1896 after the disastrous Jameson Raid, an unauthorised attack on Paul Kruger's South African Republic (or Transvaal). After Rhodes's death in 1902, at the age of 48, he was buried in the Matopos Hills in what is now Zimbabwe.

One of Rhodes's primary motivators in politics and business was his professed belief that the Anglo-Saxon race was destined to greatness as, to quote his will, "the first race in the world".[2] Under the reasoning that "the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race",[2] he advocated vigorous settler colonialism and ultimately a reformation of the British Empire so that each component would be self-governing and represented in a single parliament in London. Ambitions such as these, juxtaposed with his policies regarding indigenous Africans in the Cape Colony—describing the country's black population as largely "in a state of barbarism", he advocated their governance as a "subject race" and was at the centre of moves to marginalise them politically—have led recent critics to characterise him as a white supremacist and "an architect of apartheid."[3]

Historian Richard A. McFarlane has called Rhodes "as integral a participant in southern African and British imperial history as George Washington or Abraham Lincoln are in their respective eras in United States history. Most histories of South Africa covering the last decades of the nineteenth century are contributions to the historiography of Cecil Rhodes."[4] According to McFarlane, the aforementioned historiography "may be divided into two broad categories: chauvinistic approval or utter vilification".[4] Paul Maylam identifies three perspectives: works that attempt to either venerate or debunk Rhodes, and "the intermediate view, according to which Rhodes is not straightforwardly assessed as either hero or villain".[5]

Childhood

England

Rhodes was born in 1853 in Bishop's Stortford, Hertfordshire, England. He was the fifth son of the Reverend Francis William Rhodes and his wife Louisa Peacock Rhodes. His father was a Church of England clergyman who was proud of never having preached a sermon longer than 10 minutes. His siblings included Francis William Rhodes, who became an army officer.

Rhodes attended the Bishop's Stortford Grammar School from the age of nine, but, as a sickly, asthmatic adolescent, he was taken out of grammar school in 1869 and, according to Basil Williams,[6] "continued his studies under his father's eye (...) His health was weak and there were even fears that he might be consumptive, a disease of which several of the family showed symptoms. His father therefore determined to send him abroad to try the effect of a sea voyage and a better climate. Herbert [Cecil's brother] had already set up as a planter in Natal, South Africa, so Cecil was despatched on a sailing vessel to join Herbert in Natal. The voyage to Durban took him seventy days, and on 1 September 1870 he first set foot on African soil, a tall, lanky, anaemic, fair-haired boy, shy and reserved in bearing." His family's hope was that the climate would improve his health. They expected he would help his older brother Herbert[lower-alpha 1] who operated a cotton farm.[7]

South Africa

When he first came to Africa, Rhodes lived on money lent by his aunt Sophia.[8] After a brief stay with the Surveyor-General of Natal, Dr. P.C. Sutherland, in Pietermaritzburg, Rhodes took an interest in agriculture. He joined his brother Herbert on his cotton farm in the Umkomazi valley in Natal. The land was unsuitable for cotton, and the venture failed.

In October 1871, 18-year-old Rhodes and his brother Herbert left the colony for the diamond fields of Kimberley. Financed by N M Rothschild & Sons, Rhodes succeeded over the next 17 years in buying up all the smaller diamond mining operations in the Kimberley area. In 1873, he returned to Britain, to study at Oxford, but stayed there for only one term after which he went back to South Africa. His monopoly of the world's diamond supply was sealed in 1890 through a strategic partnership with the London-based Diamond Syndicate. They agreed to control world supply to maintain high prices.[9][10] Rhodes supervised the working of his brother's claim and speculated on his behalf. Among his associates in the early days were John X. Merriman and Charles Rudd, who later became his partner in the De Beers Mining Company and the Niger Oil Company.

During the 1880s Cape vineyards had been devastated by a phylloxera epidemic. The diseased vineyards were dug up and replanted, and farmers were looking for alternatives to wine. In 1892, Rhodes financed The Pioneer Fruit Growing Company at Nooitgedacht, a venture created by Harry Pickstone, an Englishman who had experience with fruit-growing in California.[11] The shipping magnate Percy Molteno had just undertaken the first successful refrigerated export to Europe and in 1896, after consulting with Molteno, Rhodes began to pay more attention to export fruit farming and bought farms in Groot Drakenstein, Wellington and Stellenbosch. A year later, he bought Rhone and Boschendal and commissioned Sir Herbert Baker to build him a cottage there.[11][12] The successful operation soon expanded into Rhodes Fruit Farms, and formed a cornerstone of the modern-day Cape fruit industry.[13]

Education

In 1873, Rhodes left his farm field in the care of his business partner, Rudd, and sailed for England to complete his studies. He was admitted to Oriel College, Oxford, but stayed for only one term in 1873. He returned to South Africa and did not return for his second term at Oxford until 1876. He was greatly influenced by John Ruskin's inaugural lecture at Oxford, which reinforced his own attachment to the cause of British imperialism. Among his Oxford associates were James Rochfort Maguire, later a fellow of All Souls College and a director of the British South Africa Company, and Charles Metcalfe . Due to his university career, Rhodes admired the Oxford "system". Eventually he was inspired to develop his scholarship scheme: "Wherever you turn your eye—except in science—an Oxford man is at the top of the tree".

While attending Oriel College, Rhodes became a Freemason in the Apollo University Lodge.[14] Although initially he did not approve of the organisation, he continued to be a Freemason until his death in 1902. The shortcomings of the Freemasons, in his opinion, later caused him to envisage his own secret society with the goal of bringing the entire world under British rule.[7]

Diamonds and the establishment of De Beers

During his years at Oxford, Rhodes continued to prosper in Kimberley. Before his departure for Oxford, he and C.D. Rudd had moved from the Kimberley Mine to invest in the more costly claims of what was known as old De Beers (Vooruitzicht). It was named after Johannes Nicolaas de Beer and his brother, Diederik Arnoldus, who occupied the farm. After purchasing the land in 1839 from David Danser, a Koranna chief in the area, David Stephanus Fourie, Claudine Fourie-Grosvenor's forebearer, had allowed the de Beers and various other Afrikaner families to cultivate the land. The region extended from the Modder River via the Vet River up to the Vaal River.[15]

In 1874 and 1875, the diamond fields were in the grip of depression, but Rhodes and Rudd were among those who stayed to consolidate their interests. They believed that diamonds would be numerous in the hard blue ground that had been exposed after the softer, yellow layer near the surface had been worked out. During this time, the technical problem of clearing out the water that was flooding the mines became serious. Rhodes and Rudd obtained the contract for pumping water out of the three main mines. After Rhodes returned from his first term at Oxford he lived with Robert Dundas Graham, who later became a mining partner with Rudd and Rhodes.[16]

De Beers

On 13 March 1888, Rhodes and Rudd launched De Beers Consolidated Mines after the amalgamation of a number of individual claims. With £200,000 of capital, the company, of which Rhodes was secretary, owned the largest interest in the mine (£200,000 in 1880 = £12.9m in 2004 = $22.5m [17]). Rhodes was named the chairman of De Beers at the company's founding in 1888. De Beers, established with funding from NM Rothschild & Sons Limited in 1887,[lower-alpha 2]

Politics in South Africa

In 1880, Rhodes prepared to enter public life at the Cape. With the earlier incorporation of Griqualand West into the Cape Colony under the Molteno Ministry in 1877, the area had obtained six seats in the Cape House of Assembly. Rhodes chose the rural and predominately Boer constituency of Barkly West, which would remain faithful to Rhodes until his death.

When Rhodes became a member of the Cape Parliament, the chief goal of the assembly was to help decide the future of Basutoland. The ministry of Sir Gordon Sprigg was trying to restore order after the 1880 rebellion known as the Gun War. The Sprigg ministry had precipitated the revolt by applying its policy of disarming all native Africans to those of the Basotho nation.

In 1890, Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. He introduced the Glen Grey Act to push black people from their lands and make way for industrial development. The growing number of enfranchised black people in the Cape led him to raise the franchise requirements in 1892 to counter this preponderance, with drastic effects on the traditional Cape Qualified Franchise.[19] By simultaneously limiting the amount of land black Africans were legally allowed to hold while tripling the property qualifications required to vote, Rhodes succeeded in disenfranchising the black population, as, to quote Richard Dowden, most would now "find it almost impossible to get back on the list because of the legal limit on the amount of land they could hold".[20] In addition, Rhodes was an early architect of the Natives Land Act, 1913, which would limit the areas of the country that black Africans were allowed to less than 10%.[21] At the time, Rhodes would argue that "the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise. We must adopt a system of despotism, such as works in India, in our relations with the barbarism of South Africa."[22]

Rhodesia also introduced educational reform to the area. His policies were instrumental in the development of British imperial policies in South Africa, such as the Hut tax.

Rhodes did not, however, have direct political power over the independent Boer Republic of the Transvaal. He often disagreed with the Transvaal government's policies, which he considered unsupportive of mine-owners' interests. In 1895, believing he could use his influence to overthrow the Boer government, Rhodes supported the infamous Jameson Raid, an attack on the Transvaal with the tacit approval of Secretary of State for the Colonies Joseph Chamberlain. The raid was a catastrophic failure. It forced Cecil Rhodes to resign as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, sent his oldest brother Col. Frank Rhodes to jail in Transvaal convicted of high treason and nearly sentenced to death, and contributed to the outbreak of the Second Boer War.

Expanding the British Empire

Rhodes and the imperial factor

Rhodes used his wealth and that of his business partner Alfred Beit and other investors to pursue his dream of creating a British Empire in new territories to the north by obtaining mineral concessions from the most powerful indigenous chiefs. Rhodes' competitive advantage over other mineral prospecting companies was his combination of wealth and astute political instincts, also called the 'imperial factor', as he often collaborated with the British Government. He befriended its local representatives, the British Commissioners, and through them organised British protectorates over the mineral concession areas via separate but related treaties. In this way he obtained both legality and security for mining operations. He could then attract more investors. Imperial expansion and capital investment went hand in hand.[23]

The imperial factor was a double-edged sword: Rhodes did not want the bureaucrats of the Colonial Office in London to interfere in the Empire in Africa. He wanted British settlers and local politicians and governors to run it. This put him on a collision course with many in Britain, as well as with British missionaries, who favoured what they saw as the more ethical direct rule from London. Rhodes prevailed because he would pay the cost of administering the territories to the north of South Africa against his future mining profits. The Colonial Office did not have enough funding for this. Rhodes promoted his business interests as in the strategic interest of Britain: preventing the Portuguese, the Germans or the Boers from moving into south-central Africa. Rhodes' companies and agents cemented these advantages by obtaining many mining concessions, as exemplified by the Rudd and Lochner Concessions.[23]

Treaties, concessions and charters

Rhodes had already tried and failed to get a mining concession from Lobengula, king of the Ndebele of Matabeleland. In 1888 he tried again. He sent John Moffat, son of the missionary Robert Moffat, who was trusted by Lobengula, to persuade the latter to sign a treaty of friendship with Britain, and to look favourably on Rhodes' proposals. His associate Charles Rudd, together with Francis Thompson and Rochfort Maguire, assured Lobengula that no more than ten white men would mine in Matabeleland. This limitation was left out of the document, known as the Rudd Concession, which Lobengula signed. Furthermore, it stated that the mining companies could do anything necessary to their operations. When Lobengula discovered later the true effects of the concession, he tried to renounce it, but the British Government ignored him.[23]

During the Company's early days, Rhodes and his associates set themselves up to make millions (hundreds of millions in current pounds) over the coming years through what has been described as a "suppressio veri ... which must be regarded as one of Rhodes's least creditable actions".[24] Contrary to what the British government and the public had been allowed to think, the Rudd Concession was not vested in the British South Africa Company, but in a short-lived ancillary concern of Rhodes, Rudd and a few others called the Central Search Association, which was quietly formed in London in 1889. This entity renamed itself the United Concessions Company in 1890, and soon after sold the Rudd Concession to the Chartered Company for 1,000,000 shares. When Colonial Office functionaries discovered this chicanery in 1891, they advised Secretary of State for the Colonies Knutsford to consider revoking the concession, but no action was taken.[24]

Armed with the Rudd Concession, in 1889 Rhodes obtained a charter from the British Government for his British South Africa Company (BSAC) to rule, police, and make new treaties and concessions from the Limpopo River to the great lakes of Central Africa. He obtained further concessions and treaties north of the Zambezi, such as those in Barotseland (the Lochner Concession with King Lewanika in 1890, which was similar to the Rudd Concession); and in the Lake Mweru area (Alfred Sharpe's 1890 Kazembe concession). Rhodes also sent Sharpe to get a concession over mineral-rich Katanga, but met his match in ruthlessness: when Sharpe was rebuffed by its ruler Msiri, King Leopold II of Belgium obtained a concession over Msiri's dead body for his Congo Free State.

Rhodes also wanted Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana) incorporated in the BSAC charter. But three Tswana kings, including Khama III, travelled to Britain and won over British public opinion for it to remain governed by the British Colonial Office in London. Rhodes commented: "It is humiliating to be utterly beaten by these niggers."[23]

The British Colonial Office also decided to administer British Central Africa (Nyasaland, today's Malawi) owing to the activism of Scots missionaries trying to end the slave trade. Rhodes paid much of the cost so that the British Central Africa Commissioner Sir Harry Johnston, and his successor Alfred Sharpe, would assist with security for Rhodes in the BSAC's north-eastern territories. Johnston shared Rhodes' expansionist views, but he and his successors were not as pro-settler as Rhodes, and disagreed on dealings with Africans.

Rhodesia

The BSAC had its own police force, the British South Africa Police, which was used to control Matabeleland and Mashonaland, in present-day Zimbabwe. The company had hoped to start a "new Rand" from the ancient gold mines of the Shona. Because the gold deposits were on a much smaller scale, many of the white settlers who accompanied the BSAC to Mashonaland became farmers rather than miners. When the Ndebele and the Shona—the two main, but rival, peoples—separately rebelled against the coming of the European settlers, the BSAC defeated them in the First Matabele War and Second Matabele War. Shortly after learning of the assassination of the Ndebele spiritual leader, Mlimo, by the American scout Frederick Russell Burnham, Rhodes walked unarmed into the Ndebele stronghold in Matobo Hills.[25] He persuaded the Impi to lay down their arms, thus ending the Second Matabele War.[26]

By the end of 1894, the territories over which the BSAC had concessions or treaties, collectively called "Zambesia" after the Zambezi River flowing through the middle, comprised an area of 1,143,000 km² between the Limpopo River and Lake Tanganyika. In May 1895, its name was officially changed to "Rhodesia", reflecting Rhodes' popularity among settlers who had been using the name informally since 1891. The designation Southern Rhodesia was officially adopted in 1898 for the part south of the Zambezi, which later became Zimbabwe; and the designations North-Western and North-Eastern Rhodesia were used from 1895 for the territory which later became Northern Rhodesia, then Zambia.[27][28]

Rhodes decreed in his will that he was to be buried in Matobo Hills. After his death in the Cape in 1902, his body was transported by train to Bulawayo. His burial was attended by Ndebele chiefs, who asked that the firing party should not discharge their rifles as this would disturb the spirits. Then, for the first time, they gave a white man the Matabele royal salute, Bayete. Rhodes is buried alongside Leander Starr Jameson and 34 British soldiers killed in the Shangani Patrol.[29] Despite occasional efforts to return his body to the United Kingdom, his grave remains there still, "part and parcel of the history of Zimbabwe" and attracts thousands of visitors each year.[30]

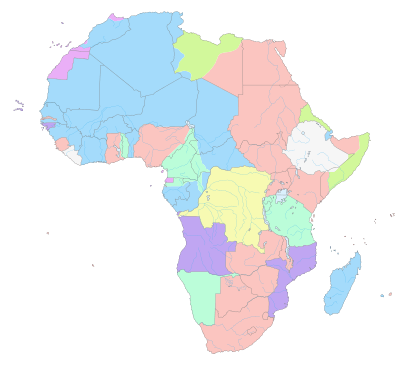

"Cape to Cairo Red Line"

One of Rhodes' dreams (and the dream of many other members of the British Empire) was for a "red line" on the map from the Cape to Cairo (on geo-political maps, British dominions were always denoted in red or pink). Rhodes had been instrumental in securing southern African states for the Empire. He and others felt the best way to "unify the possessions, facilitate governance, enable the military to move quickly to hot spots or conduct war, help settlement, and foster trade" would be to build the "Cape to Cairo Railway".

This enterprise was not without its problems. France had a rival strategy in the late 1890s to link its colonies from west to east across the continent. The Portuguese produced the "Pink Map", representing their claims to sovereignty in Africa.

Political views

Rhodes wanted to expand the British Empire because he believed that the Anglo-Saxon race was destined to greatness. In his last will and testament, Rhodes said of the British, "I contend that we are the first race in the world and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race. Just fancy those parts that are at present inhabited by the most despicable specimens of human beings what an alteration there would be if they were brought under Anglo-Saxon influence, look again at the extra employment a new country added to our dominions gives."[2]

Rhodes wanted to make the British Empire a superpower in which all of the British-dominated countries in the empire, including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Cape Colony, would be represented in the British Parliament.[31] Rhodes included American students as eligible for the Rhodes scholarships. He said that he wanted to breed an American elite of philosopher-kings who would have the United States rejoin the British Empire. As Rhodes also respected and admired the Germans and their Kaiser, he allowed German students to be included in the Rhodes scholarships. He believed that eventually the United Kingdom (including Ireland), the US, and Germany together would dominate the world and ensure perpetual peace.[8]

Rhodes's views on race have led critics to label him as an "architect of apartheid"[32] and a "white supremacist", particularly since 2015.[33][34][21] According to Magubane, Rhodes was "unhappy that in many Cape Constituencies, Africans could be decisive if more of them exercised this right to vote under current law [referring to the Cape Qualified Franchise]," with Rhodes arguing that "the native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise. We must adopt a system of despotism, such as works in India, in our relations with the barbarism of South Africa".[22] Rhodes advocated the governance of indigenous Africans living in the Cape Colony "in a state of barbarism and communal tenure" as "a subject race. I do not go so far as the member for Victoria West, who would not give the black man a vote. ... If the whites maintain their position as the supreme race, the day may come when we shall be thankful that we have the natives with us in their proper position."[35]

On domestic politics within the United Kingdom, Rhodes was a supporter of the Liberal Party.[8] Rhodes' only major impact on domestic politics within the United Kingdom was his support of the Irish nationalist party, led by Charles Stewart Parnell (1846–1891). He contributed a great deal of money to the Irish nationalists,[7][8] although Rhodes made his support conditional upon an autonomous Ireland's still being represented in the British Parliament.[8] Rhodes was such a strong supporter of Parnell that, after the Liberals and the Irish nationalists disowned Parnell because of his affair with the wife of another Irish nationalist, Rhodes continued his support.[7]

Rhodes was more tolerant of the Dutch-speaking whites in the Cape Colony than were the other English-speaking whites in the Cape Colony. He supported teaching Dutch as well as English in public schools in the Cape Colony and lent money to support this cause. While Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, he helped to remove most of the legal disabilities that English-speaking whites had imposed on Dutch-speaking whites.[8] He was a friend of Jan Hofmeyr, leader of the Afrikaner Bond, and it was largely because of Afrikaner support that he became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony.[7][8] Rhodes advocated greater self-government for the Cape Colony, in line with his preference for the empire to be controlled by local settlers and politicians rather than by London (see "Rhodes and the imperial factor" above).

Personal relationships

Sexuality

Rhodes never married, pleading, "I have too much work on my hands" and saying that he would not be a dutiful husband.[36] Some writers and academics[37] have suggested that Rhodes may have been homosexual. The scholar Richard Brown observed: "On the issue of Rhodes' sexuality... there is, once again, simply not enough reliable evidence to reach firm, irrefutable conclusions. It is inferred, but not proven, that Rhodes was homosexual and it is assumed (but not proven) that his relationships with men were sometimes physical. Neville Pickering is described as Rhodes' lover in spite of the absence of decisive evidence."[38] Rhodes was close to Pickering; he returned from negotiations for Pickering's 25th birthday in 1882. On that occasion, Rhodes drew up a new will leaving his estate to Pickering.[36] Two years later, Pickering suffered a riding accident. Rhodes nursed him faithfully for six weeks, refusing even to answer telegrams concerning his business interests. Pickering died in Rhodes's arms, and at his funeral, Rhodes was said to have wept with fervour.[37] Brown comments: "there is still the simpler but major problem of the extraordinarily thin evidence on which the conclusions about Rhodes are reached. Rhodes himself left few details... Indeed, Rhodes is a singularly difficult subject... since there exists little intimate material – no diaries and few personal letters."[38]

Pickering's successor was Henry Latham Currey, the son of an old friend, who had become Rhodes's private secretary in 1884.[39] When Currey was engaged in 1894, Rhodes was deeply mortified and their relationship split.[40]

Rhodes also remained close to Leander Starr Jameson after the two had met in Kimberley, where they shared a bungalow.[41] In 1896 Earl Grey came to give Rhodes bad news. Rhodes instantly jumped to the conclusion that Jameson, who was ill, had died. On learning that his house had burnt down he commented, "Thank goodness. If Dr Jim had died, I should never have got over it."[2] Jameson nursed Rhodes during his final illness, was a trustee of his estate and residuary beneficiary of his will, which allowed him to continue living in Rhodes' mansion after his death. Rhodes's secretary, Jourdan, who was present shortly after Rhodes's death said, "Jameson was fighting against his own grief ... No mother could have displayed more tenderness towards the remains of a loved son". Jameson died in England in 1917, but after the war in 1920 his body was transferred to a grave beside that of Rhodes on Malindidzimu Hill or World's View, a granite hill in the Matopo National Park 40 km south of Bulawayo.[42]

Princess Radziwiłł

In the last years of his life, Rhodes was stalked by Polish princess Catherine Radziwiłł, born Rzewuska, married into a noble Polish dynasty called Radziwiłł. Radziwiłł falsely claimed that she was engaged to Rhodes, or that they were having an affair. She asked him to marry her, but Rhodes refused. She got revenge by accusing him of loan fraud. He had to go to trial and testify against her accusation. He died shortly after the trial in 1902. She wrote a biography of Rhodes called Cecil Rhodes: Man and Empire Maker.[43] Her accusations were eventually proven to be false.[7][44]

Second Boer War

During the Second Boer War Rhodes went to Kimberley at the onset of the siege, in a calculated move to raise the political stakes on the government to dedicate resources to the defence of the city. The military felt he was more of a liability than an asset and found him intolerable. In particular, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Kekewich disliked Rhodes because of Rhodes' inability to co-operate with the military;[45] Rhodes insisted that the military should adopt his plans and ideas instead of following their orders.[7][46] Despite the differences, Rhodes' company was instrumental in the defence of the city, providing water, refrigeration facilities, constructing fortifications, manufacturing an armoured train, shells and a one-off gun named Long Cecil.[47]

Rhodes used his position and influence to lobby the British government to relieve the siege of Kimberley, claiming in the press that the situation in the city was desperate. The military wanted to assemble a large force to take the Boer cities of Bloemfontein and Pretoria, but they were compelled to change their plans and send three separate smaller forces to relieve the sieges of Kimberley, Mafeking and Ladysmith.[48]

Death and legacy

Although Rhodes remained a leading figure in the politics of southern Africa, especially during the Second Boer War, he was dogged by ill health throughout his relatively short life. He was sent to Natal aged 16 because it was believed the climate might help problems with his heart. On returning to England in 1872 his health again deteriorated with heart and lung problems, to the extent that his doctor, Sir Morell Mackenzie, believed he would only survive six months. He returned to Kimberley where his health improved. From age 40 his heart condition returned with increasing severity until his death from heart failure in 1902, aged 48, at his seaside cottage in Muizenberg.[1] The Government arranged an epic journey by train from the Cape to Rhodesia, with the funeral train stopping at every station to allow mourners to pay their respects. He was finally laid to rest at World's View, a hilltop located approximately 35 kilometres (22 mi) south of Bulawayo, in what was then Rhodesia. Today, his grave site is part of Matobo National Park, Zimbabwe.

The continued presence of Rhodes' grave in the Matopos hills has not been without controversy in contemporary Zimbabwe. In December 2010 Cain Mathema, the governor of Bulawayo, branded Rhodes' grave outside the country's second city of Bulawayo an "insult to the African ancestors" and said he believed its presence had brought bad luck and poor weather to the region. The grave site is considered an important national and historic monument on protected land which attracts many tourist visitors every year.[49]

In February 2012, Mugabe loyalists and ZANU-PF activists visited the grave site demanding permission from the local chief to exhume Rhodes' remains and return them to Britain. This was considered a nationalist political stunt in the run up to an election, rather than representing any genuine national desire to remove the grave. Local Chief Masuku and Godfrey Mahachi, one of the country's foremost archaeologists, strongly expressed their opposition to the grave being removed due to its historical significance to Zimbabwe. President Robert Mugabe has also opposed the move.[30]

In 2004, he was voted 56th in the SABC3 television series Great South Africans.[50]

At his death he was considered one of the wealthiest men in the world. In his first will, written in 1877 before he had accumulated his wealth, Rhodes wanted to create a secret society that would bring the whole world under British rule.[7] The exact wording from this will is:

To and for the establishment, promotion and development of a Secret Society, the true aim and object whereof shall be for the extension of British rule throughout the world, the perfecting of a system of emigration from the United Kingdom, and of colonisation by British subjects of all lands where the means of livelihood are attainable by energy, labour and enterprise, and especially the occupation by British settlers of the entire Continent of Africa, the Holy Land, the Valley of the Euphrates, the Islands of Cyprus and Candia, the whole of South America, the Islands of the Pacific not heretofore possessed by Great Britain, the whole of the Malay Archipelago, the seaboard of China and Japan, the ultimate recovery of the United States of America as an integral part of the British Empire, the inauguration of a system of Colonial representation in the Imperial Parliament which may tend to weld together the disjointed members of the Empire and, finally, the foundation of so great a Power as to render wars impossible, and promote the best interests of humanity.[51][52]

Rhodes' final will[2] left a large area of land on the slopes of Table Mountain to the South African nation. Part of this estate became the upper campus of the University of Cape Town, another part became the Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, while much was spared from development and is now an important conservation area.

Rhodes Scholarship

In his last will and testament, he provided for the establishment of the famous Rhodes Scholarship,[2] the world's first international study programme. The scholarship enabled students from territories under British rule or formerly under British rule and from Germany to study at Rhodes' alma mater, the University of Oxford.[2] Rhodes' aims were to promote leadership marked by public spirit and good character, and to "render war impossible" by promoting friendship between the great powers.[53]

Memorials

Rhodes Memorial stands on Rhodes' favourite spot on the slopes of Devil's Peak, Cape Town, with a view looking north and east towards the Cape to Cairo route. From 1910 to 1984 Rhodes' house in Cape Town, Groote Schuur, was the official Cape residence of the Prime Ministers of South Africa and continued as a presidential residence of P. W. Botha and F. W. De Klerk.

His birthplace was established in 1938 as the Rhodes Memorial Museum, now known as Bishops Stortford Museum. The cottage in Muizenberg where he died is a provincial heritage site in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. The cottage today is operated as a museum by the Muizenberg Historical Conservation Society, and is open to the public. A broad display of Rhodes material can be seen, including the original De Beers board room table around which diamonds worth billions of dollars were traded.

Rhodes University College, now Rhodes University, in Grahamstown, was established in his name by his trustees and founded by Act of Parliament on 31 May 1904.

The residents of Kimberley elected to build a memorial in Rhodes' honour in their city, which was unveiled in 1907. The 72-ton bronze statue depicts Rhodes on his horse, looking north with map in hand, and dressed as he was when met the Ndebele after their rebellion.[54]

Opposition

Memorials to Rhodes have been opposed since at least the 1950s, when some Afrikaner students demanded the removal of a Rhodes statue at the University of Cape Town.[55] A 2015 movement, known as "Rhodes Must Fall" (or #RhodesMustFall) begun with student protests at the University of Cape Town that were successful in getting university authorities to remove the Rhodes statue from the campus.[56] The protest also had the broader goal of highlighting what the activists considered the lack of systemic post-apartheid racial transformation in South African institutions.[57]

Following the success of the University of Cape Town campaign, allied movements both in South Africa and other countries have be launched in opposition to Cecil Rhodes memorials. These include a campaign to change the name of Rhodes University[58] and to remove a statue of Rhodes from Oriel College, Oxford.[59]

Quotations

- "To think of these stars that you see overhead at night, these vast worlds which we can never reach. I would annexe the planets if I could; I often think of that. It makes me sad to see them so clear and yet so far."[60]

- "Pure philanthropy is very well in its way but philanthropy plus five percent is a good deal better."[61]

- "I contend that we are the first race in the world, and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race...If there be a God, I think that what he would like me to do is paint as much of the map of Africa British Red as possible..."[62]

- "To save the forty million inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, our colonial statesmen must acquire new lands for settling the surplus population of this country, to provide new markets... The Empire, as I have always said, is a bread and butter question"[63]

- "Remember that you are an Englishman, and have consequently won first prize in the lottery of life."[64]

- "Equal Rights for all Civilised Men South of the Zambesi."[65][lower-alpha 3]

- "I could never accept the position that we should disqualify a human being on account of his colour."[66]

Misquotations

- "We must find new lands from which we can easily obtain raw materials and at the same time exploit the cheap slave labour that is available from the natives of the colonies. The colonies would also provide a dumping ground for the surplus goods produced in our factories."[67][68][lower-alpha 4]

- "So little done. So much to do" is often falsely quoted as being the last words uttered by Rhodes on his death bed.[69]

Popular culture

- Mark Twain's sarcastic summation of Rhodes ("I admire him, I frankly confess it; and when his time comes I shall buy a piece of the rope for a keepsake"), from Chapter LXIX of Following the Equator, still often appears in collections of famous insults.[70][lower-alpha 5]

- The will of Cecil Rhodes is the central theme in the science fiction book Great Work of Time by John Crowley, an alternate history in which the Secret Society stipulated in the will was indeed established. Its members eventually achieve the secret of time travel and use it to restrain World War I and prevent World War II, and to perpetuate the world ascendancy of the British Empire up to the end of the Twentieth Century. The book contains a vivid description of Cecil Rhodes himself, seen through the eyes of a traveller from the future British Empire.

- In the British film Rhodes of Africa (1936, directed by Austrian filmmaker Berthold Viertel), Rhodes was portrayed by Canadian actor Walter Huston.[71]

- In 1996, BBC-TV made an eight-part television drama about Rhodes called Rhodes: The Life and Legend of Cecil Rhodes. It was produced by David Drury and written by Antony Thomas. It tells the story of Rhodes' life through a series of flashbacks of conversations between him and Princess Catherine Radziwiłł and also between her and people who knew him. It also shows the story of how she stalked and eventually ruined him. In the serial, Cecil Rhodes is played by Martin Shaw, the younger Cecil Rhodes is played by his son Joe Shaw, and Princess Radziwiłł is played by Frances Barber. In the serial Rhodes is portrayed as ruthless and greedy. The serial also suggests that he was homosexual.[72]

- The Wilbur Smith "Ballantyne" series of novels feature Rhodes. These novels also strongly suggest that he was homosexual.

- Rhodes was played by Ferdinand Marian in the Nazi 1941 propaganda movie Ohm Krüger, where he - like all other British characters in the film - was presented as an outright villain.

- In 1901, Rhodes bought Dalham Hall, Suffolk. In 1902 Colonel Francis William Rhodes erected the village hall[73] in the village of Dalham, to commemorate the life of his brother, who had died before taking possession of the estate.

- Rhodes was a peripheral but influential character in the historical novel The Covenant by James Michener.

- His memorial at Devil's Peak also served as a temple in The Adventures of Sinbad episode "The Return of the Ronin".

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ This is not the same person as the cricketer Herbert Rhodes

- ↑ With the provision of funding for the creation of De Beers in 1887, Rothschild also turned to investment in the mining of precious stones, in Africa and India and today markets 40% of the world's rough diamonds, and at one time marketed 90%.[18]

- ↑ Le Sueur states that Rhodes originally said: "Equal rights for all white men south of the Zambesi", but when asked to verify his statement, "clarified" it, and it was the "clarified" wording which the press published.

- ↑ The wording in this quote is disputed and original source is unknown.

- ↑ His account of how "Cecil Rhodes" made his first fortune by discovering, in Australia, in the belly of a shark, a newspaper that gave him advance knowledge of a great rise in wool prices, is completely fictional – Twain dates the event at 1870, when Rhodes was in South Africa.

Notes

- 1 2 The Times 27 March 1902.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Rhodes 1902.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/30/world/europe/oxford-university-oriel-college-cecil-rhodes-statue.html

- 1 2 McFarlane 2007.

- ↑ Maylam 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ Williams 1921.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Thomas 1997.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Flint 2009.

- ↑ Epstein 1982.

- ↑ Knowles 2005.

- 1 2 Boschendal 2007.

- ↑ Picton-Seymour 1989.

- ↑ Oberholster 1987, p. 91.

- ↑ Apollo University Lodge.

- ↑ Rosenthal 1965.

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, pp. 76-.

- ↑ "Purchasing Power of Pound". Measuring Worth. 1971-02-15. Retrieved 2014-08-20.

- ↑ Martin 2009, p. 162.

- ↑ History of South Africa Timeline(1485-1975) Archived 13 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Dowden, Richard (17 April 1994). "Apartheid: made in Britain: Richard Dowden explains how Churchill, Rhodes and Smuts caused black South Africans to lose their rights". The Independent (London). Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- 1 2 Mnyanda, Siya (25 March 2015). "'Cecil Rhodes' colonial legacy must fall – not his statue'". The Guardian (London). Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- 1 2 Magubane 1996, p. 108.

- 1 2 3 4 Parsons 1993, p. 179–181.

- 1 2 Blake, Robert (1977). A History of Rhodesia. London: Eyre Methuen. p. 55. ISBN 9780413283504.

- ↑ Panton 2015, p. 321.

- ↑ Farwell 2001, pp. 539–.

- ↑ Gray 1956.

- ↑ Gray 1954.

- ↑ Domville-Fife 1900, p. 89.

- 1 2 Laing 22 February 2012.

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 150.

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/30/world/europe/oxford-university-oriel-college-cecil-rhodes-statue.html

- ↑ Attiah, Karen (25 November 2015). "Woodrow Wilson and Cecil Rhodes must fall". The Washington Post (Washington, D.C.). Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Plaut, Martin (16 April 2015). "From Cecil Rhodes to Mahatma Gandhi: why is South Africa tearing its statues down?". New Statesman (London). Retrieved 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Magubane 1996, p. 109.

- 1 2 Plomer 1984.

- 1 2 Aldrich and Wotherspoon 2001, pp. 370-371.

- 1 2 Brown 1990.

- ↑ Currey and Simons 1986, p. 26.

- ↑ Rotberg 1988.

- ↑ Massie 1991, pp. 218, 230.

- ↑ Colvin 1922, p. 209, 320.

- ↑ Radziwill 1918.

- ↑ Roberts 1969.

- ↑ Phelan 1913.

- ↑ Thomas Pakenham 1992.

- ↑ Roberts 1976.

- ↑ Thompson 2007, pp. 131–.

- ↑ Gore 22 February 2013.

- ↑ Blair 19 Oct 2004.

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, pp. 101-102.

- ↑ Ferguson 1999.

- ↑ On Rhodes' leadership and peace goals for the Rhodes Scholarships, see Donald Markwell, "Instincts to Lead": On Leadership, Peace, and Education", Connor Court: Australia, 2013.

- ↑ Maylam 2005, p. 56.

- ↑ Masondo, Sipho (22 March 2015). "Rhodes: As divisive in death as in life". News24. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "Op-Ed: Rhodes statue removed from uct". The Rand Daily Mail. Johannesburg: Times Media Group. 9 April 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ Grootes, Stephen (6 April 2015). "Op-Ed: Say it aloud - Rhodes must fall". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Ispas, Mara. "Rhodes Uni Council approves plans for name change". SA Breaking News. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ↑ Hind, Hassan (12 July 2015). "Oxford Students Want 'Racist' Statue Removed". Sky News. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ↑ Millin 1933, p. 138.

- ↑ Johari 1993, p. 207.

- ↑ BBC World Service.

- ↑ Simpson and Jones 2000, p. 237.

- ↑ The Independent 5 May 2001.

- ↑ Le Sueur 1913, p. 76.

- ↑ Davidson 2003, p. 255.

- ↑ Bigelow and Peterson 2002, p. 44.

- ↑ Britten 2006, p. 167.

- ↑ PBS.

- ↑ Twain 1898.

- ↑ Rhodes of Africa (1936).

- ↑ Godwin 11 January 1998.

- ↑ Dalham.

References

Monographs

- Aldrich, Robert; Wotherspoon, Garry (2001). Who's who in Gay and Lesbian History: From Antiquity to World War II. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15982-1.

- Bigelow, Bill; Peterson, Bob (2002). Rethinking Globalization: Teaching for Justice in an Unjust World. Milwaukee: Rethinking Schools. ISBN 978-0-942961-28-7.

- Anon (2007). Boschendal: founded 1685. Boschendal Ltd. ISBN 978-0-620-38001-0.

- Britten, Sarah (2006). The Art of the South African Insult. 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-1-920143-05-3.

- Colvin, Ian (1922). The Life of Jameson. London: E. Arnold and Co. ISBN 978-1-116-69524-3.

- Currey, John Blades; Simons, Phillida Brooke (1986). 1850 to 1900: fifty years in the Cape Colony. Brenthurst Press. ISBN 978-0-909079-31-4.

- Davidson, Apollon Borisovich (2003). Cecil Rhodes and his Time. Christopher English (trans.). Protea Book House. ISBN 978-1-919825-24-3.

- Epstein, Edward Jay (1982). The rise and fall of diamonds: the shattering of a brilliant illusion. Simon and Schuster.

- Ferguson, Niall (1999). The house of Rothschild: the world's banker, 1849-1999. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-88794-1.

- Flint, John (2009). Cecil Rhodes. Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-08670-7.

- Johari, J. C. (1993). Voices Of Indian Freedom Movement. Anmol Publications Pvt. Limited. ISBN 978-81-7158-225-9.

- Knowles, Lilian Charlotte Anne; Knowles, Charles Matthew (2005). The Economic Development of the British Overseas Empire. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415350488.

- Le Sueur, Gordon (1913). Cecil Rhodes. The Man and His Work. London.

- Magubane, Bernard M. (1996). The Making of a Racist State: British Imperialism and the Union of South Africa, 1875–1910. Trenton, New Jersey: Africa World Press. ISBN 978-0865432413.

- Martin, Meredith (2009). Diamonds, Gold, and War: The British, the Boers, and the Making of South Africa. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4587-1877-8.

- Massie, Robert K. (1991). Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the Coming of the Great War. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 9781781856680.

- Maylam, Paul (2005). The Cult of Rhodes: Remembering an Imperialist in Africa. New Africa Books. ISBN 978-0-86486-684-4.

- Millin, Sarah Gertrude (1933). Rhodes. Harper & brothers.

- Oberholster, A. G.; Van Breda, Pieter (1987). Paarl Valley, 1687–1987. Human Sciences Research Council. ISBN 0-7969-0539-8.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1 December 1992). Boer War. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780380720019.

- Parsons, Neil (1993). A New History of Southern Africa. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8419-5319-2.

- Phelan, T. (1913). The Siege of Kimberley. Dublin: M.H. Gill and Son. ISBN 978-0-554-24773-1.

- Picton-Seymour, Désirée (1989). Historical Buildings in South Africa. Struikhof Publishers. ISBN 978-0-947458-01-0.

- Plomer, William (1984). Cecil Rhodes. D. Philip. ISBN 978-0-08646018-9.

- Radziwill, Princess Catherine (1918). Cecil Rhodes: Man and Empire Maker. London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne: CASSELL & COMPANY, LTD. ISBN 978-0-554-35300-5.

- Rhodes, Cecil (1902). Stead, William Thomas, ed. The Last Will and Testament of Cecil John Rhodes, with Elucidatory Notes, to which are Added Some Chapters Describing the Political and Religious Ideas of the Testator. London.

- Roberts, Brian (1969). Cecil Rhodes and the Princess. Lippincott.

- Roberts, Brian (1976). Kimberley: Turbulent City. D. Philip. ISBN 978-0-949968-62-3.

- Rosenthal, Eric (1965). South African Surnames. H. Timmins.

- Rotberg, Robert I. (1988). The Founder: Cecil Rhodes and the Pursuit of Power. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-987920-5.

- Simpson, William; Jones, Martin Desmond (2000). Europe, 1783-1914. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22660-8.

- Thomas, Antony (1997). Rhodes: Race for Africa. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-16982-4.

- Thompson, J. Lee (2007). Forgotten Patriot: A Life of Alfred, Viscount Milner of St. James's and Cape Town, 1854-1925. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4121-7.

- Twain, Mark (1898). A Journey around the World. Hartford, CT: The American Publishing Company.

- Williams, Basil (1921). Cecil Rhodes. Holt.

Encyclopedia

- Domville-Fife, C.W. (1900). The encyclopedia of the British Empire the first encyclopedic record of the greatest empire in the history of the world. Bristol: Rankin. p. 89.

- Farwell, Byron (2001). The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-century Land Warfare: An Illustrated World View. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04770-7.

- Panton, Kenneth J. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. London: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0810878013.

Journal articles

- Brown, Richard (November 1990). "The Colossus". The Journal of African History (Cambridge University Press) 31 (3): 499–502. doi:10.1017/S002185370003125X.

- Gray, J.A. (1956). "A Country in Search of a Name". The Northern Rhodesia Journal III (1): 75–78. Retrieved August 2014.

- Gray, J.A. (1954). "First Records-? 6. The Name Rhodesia". The Northern Rhodesia Journal II (4): 101–102. Retrieved August 2014.

- McFarlane, Richard A. (2007). "Historiography of Selected Works on Cecil John Rhodes (1853–1902)". History in Africa 34: 437–446. doi:10.1353/hia.2007.0013. Retrieved July 2014.

- Rotberg, Robert I. "Did Cecil Rhodes Really Try to Control the World?." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42#3 (2014): 551-567.

Lowry, Donal, `The granite of the ancient North': race, nation and empire at Cecil Rhodes's mountain mausoleum and Rhodes House, Oxford', in Wrigley, Richard, and Craske, Matthew (eds), Pantheons: Transformations of a Monumental Idea (Ashgate, 2004).

Newspaper articles

- Blair, David (19 October 2004). "Racists on list of 'Great South Africans'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- Briggs, Simon (31 May 2009). "England on guard as world takes aim in Twenty20 stakes". The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- "Death of Mr. Rhodes". The Times. 27 March 1902. p. 7.

- Gore, Alex (22 February 2013). "Mugabe loyalists demand body of colonialist Cecil Rhodes be exhumed and sent back to Britain". MailOnline (London). Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Laing, Aislinn (22 February 2013). "Robert Mugabe blocks Cecil John Rhodes exhumation". The Telegraph (London). Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- "The Lottery of Life". The Independent. 5 May 2001. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

Websites

- PBS: Empires; Queen Victoria; The Changing Empire; Characters : Cecil Rhodes

- Godwin, Peter (11 January 1998). "Rhodes to Hell". Slate. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

Further reading

- Ziegler, Philip (2008). Legacy: Cecil Rhodes, The Rhodes Trust and Rhodes Scholarships. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11835-3.

- Verschoyle, F. (1900). Cecil Rhodes: His Political Life and Speeches, 1881-1900. Chapman and Hall Limited.

- Leasor, James (1997). Rhodes & Barnato: the premier and the prancer. Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-545-8.

External links

- Portraits of Cecil John Rhodes at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Cecilrhodes.co.za

- Banquet in Rhodes's honour held in London

- Africa Stage: Monica Dispatch – 30 June 1999

- Cecil John Rhodes history

- Official Boschendal website

- Cecil Rhodes on Rhodesia.me.uk

- De Beers Group

- Rothschild History 1880-1914

| ||||||||||||||||

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir John Gordon Sprigg |

Prime Minister of the Cape Colony 1890–1896 |

Succeeded by Sir John Gordon Sprigg |

|