Cauchy sequence

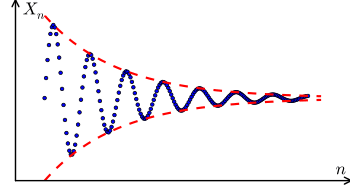

shown in blue, as

shown in blue, as  versus

versus  If the space containing the sequence is complete, the "ultimate destination" of this sequence (that is, the limit) exists.

If the space containing the sequence is complete, the "ultimate destination" of this sequence (that is, the limit) exists.

In mathematics, a Cauchy sequence (French pronunciation: [koʃi]; English pronunciation: /ˈkoʊʃiː/ KOH-shee), named after Augustin-Louis Cauchy, is a sequence whose elements become arbitrarily close to each other as the sequence progresses.[1] More precisely, given any small positive distance, all but a finite number of elements of the sequence are less than that given distance from each other.

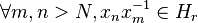

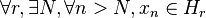

Note: it is not sufficient for each term to become arbitrarily close to the preceding term. For instance,  does not converge. Rather, it is required for a given N that any pair m,n > N we have

does not converge. Rather, it is required for a given N that any pair m,n > N we have

The utility of Cauchy sequences lies in the fact that in a complete metric space (one where all such sequences are known to converge to a limit), the criterion for convergence depends only on the terms of the sequence itself, as opposed to the definition of convergence, which uses the limit value as well as the terms. This is often exploited in algorithms, both theoretical and applied, where an iterative process can be shown relatively easily to produce a Cauchy sequence, consisting of the iterates, thus fulfilling a logical condition, such as termination.

The notions above are not as unfamiliar as they might at first appear. The customary acceptance of the fact that any real number x has a decimal expansion is an implicit acknowledgment that a particular Cauchy sequence of rational numbers (whose terms are the successive truncations of the decimal expansion of x) has the real limit x. In some cases it may be difficult to describe x independently of such a limiting process involving rational numbers.

Generalizations of Cauchy sequences in more abstract uniform spaces exist in the form of Cauchy filters and Cauchy nets.

In real numbers

A sequence

of real numbers is called a Cauchy sequence, if for every positive real number ε, there is a positive integer N such that for all natural numbers m, n > N

where the vertical bars denote the absolute value. In a similar way one can define Cauchy sequences of rational or complex numbers. Cauchy formulated such a condition by requiring  to be infinitesimal for every pair of infinite m, n.

to be infinitesimal for every pair of infinite m, n.

In a metric space

To define Cauchy sequences in any metric space X, the absolute value |xm - xn| is replaced by the distance d(xm, xn) (where d : X × X → R with some specific properties, see Metric (mathematics)) between xm and xn.

Formally, given a metric space (X, d), a sequence

- x1, x2, x3, ...

is Cauchy, if for every positive real number ε > 0 there is a positive integer N such that for all positive integers m, n > N, the distance

- d(xm, xn) < ε.

Roughly speaking, the terms of the sequence are getting closer and closer together in a way that suggests that the sequence ought to have a limit in X. Nonetheless, such a limit does not always exist within X.

Completeness

A metric space X in which every Cauchy sequence converges to an element of X is called complete.

Examples

The real numbers are complete under the metric induced by the usual absolute value, and one of the standard constructions of the real numbers involves Cauchy sequences of rational numbers. In this construction, each equivalence class of Cauchy sequences of rational numbers with a certain tail behavior—that is, each class of sequences that get arbitrarily close to one another— is a real number.

A rather different type of example is afforded by a metric space X which has the discrete metric (where any two distinct points are at distance 1 from each other). Any Cauchy sequence of elements of X must be constant beyond some fixed point, and converges to the eventually repeating term.

Counter-example: rational numbers

The rational numbers Q are not complete (for the usual distance):

There are sequences of rationals that converge (in R) to irrational numbers; these are Cauchy sequences having no limit in Q. In fact, if a real number x is irrational, then the sequence (xn), whose n-th term is the truncation to n decimal places of the decimal expansion of x, gives a Cauchy sequence of rational numbers with irrational limit x. Irrational numbers certainly exist, for example:

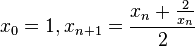

- The sequence defined by

consists of rational numbers (1, 3/2, 17/12,...), which is clear from the definition; however it converges to the irrational square root of two, see Babylonian method of computing square root.

consists of rational numbers (1, 3/2, 17/12,...), which is clear from the definition; however it converges to the irrational square root of two, see Babylonian method of computing square root. - The sequence

of ratios of consecutive Fibonacci numbers which, if it converges at all, converges to a limit

of ratios of consecutive Fibonacci numbers which, if it converges at all, converges to a limit  satisfying

satisfying  , and no rational number has this property. If one considers this as a sequence of real numbers, however, it converges to the real number

, and no rational number has this property. If one considers this as a sequence of real numbers, however, it converges to the real number  , the Golden ratio, which is irrational.

, the Golden ratio, which is irrational. - The values of the exponential, sine and cosine functions, exp(x), sin(x), cos(x), are known to be irrational for any rational value of x≠0, but each can be defined as the limit of a rational Cauchy sequence, using, for instance, the Maclaurin series.

Counter-example: open interval

The open interval X = (0, 2) in the set of real numbers with an ordinary distance in R is not a complete space: there is a sequence xn = 1/n in it, which is Cauchy (for arbitrarily small distance bound d > 0 all terms xn of n > 1/d fit in the (0, d) interval), however does not converge in X — its 'limit', number 0, does not belong to the space X.

Other properties

- Every convergent sequence (with limit s, say) is a Cauchy sequence, since, given any real number ε > 0, beyond some fixed point, every term of the sequence is within distance ε/2 of s, so any two terms of the sequence are within distance ε of each other.

- Every Cauchy sequence of real (or complex) numbers is bounded (since for some N, all terms of the sequence from the N-th onwards are within distance 1 of each other, and if M is the largest absolute value of the terms up to and including the N-th, then no term of the sequence has absolute value greater than M+1).

- In any metric space, a Cauchy sequence which has a convergent subsequence with limit s is itself convergent (with the same limit), since, given any real number r > 0, beyond some fixed point in the original sequence, every term of the subsequence is within distance r/2 of s, and any two terms of the original sequence are within distance r/2 of each other, so every term of the original sequence is within distance r of s.

These last two properties, together with a lemma used in the proof of the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem, yield one standard proof of the completeness of the real numbers, closely related to both the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem and the Heine–Borel theorem. The lemma in question states that every bounded sequence of real numbers has a convergent monotonic subsequence. Given this fact, every Cauchy sequence of real numbers is bounded, hence has a convergent subsequence, hence is itself convergent. It should be noted, though, that this proof of the completeness of the real numbers implicitly makes use of the least upper bound axiom. The alternative approach, mentioned above, of constructing the real numbers as the completion of the rational numbers, makes the completeness of the real numbers tautological.

One of the standard illustrations of the advantage of being able to work with Cauchy sequences and make use of completeness is provided by consideration of the summation of an infinite series of real numbers

(or, more generally, of elements of any complete normed linear space, or Banach space). Such a series

is considered to be convergent if and only if the sequence of partial sums

is considered to be convergent if and only if the sequence of partial sums  is convergent, where

is convergent, where

. It is a routine matter

to determine whether the sequence of partial sums is Cauchy or not,

since for positive integers p > q,

. It is a routine matter

to determine whether the sequence of partial sums is Cauchy or not,

since for positive integers p > q,

If  is a uniformly continuous map between the metric spaces M and N and (xn) is a Cauchy sequence in M, then

is a uniformly continuous map between the metric spaces M and N and (xn) is a Cauchy sequence in M, then  is a Cauchy sequence in N. If

is a Cauchy sequence in N. If  and

and  are two Cauchy sequences in the rational, real or complex numbers, then the sum

are two Cauchy sequences in the rational, real or complex numbers, then the sum  and the product

and the product  are also Cauchy sequences.

are also Cauchy sequences.

Generalizations

In topological vector spaces

There is also a concept of Cauchy sequence for a topological vector space  : Pick a local base

: Pick a local base  for

for  about 0; then (

about 0; then ( ) is a Cauchy sequence if for each member

) is a Cauchy sequence if for each member  , there is some number

, there is some number  such that whenever

such that whenever

is an element of

is an element of  . If the topology of

. If the topology of  is compatible with a translation-invariant metric

is compatible with a translation-invariant metric  , the two definitions agree.

, the two definitions agree.

In topological groups

Since the topological vector space definition of Cauchy sequence requires only that there be a continuous "subtraction" operation, it can just as well be stated in the context of a topological group: A sequence  in a topological group

in a topological group  is a Cauchy sequence if for every open neighbourhood

is a Cauchy sequence if for every open neighbourhood  of the identity in

of the identity in  there exists some number

there exists some number  such that whenever

such that whenever  it follows that

it follows that  . As above, it is sufficient to check this for the neighbourhoods in any local base of the identity in

. As above, it is sufficient to check this for the neighbourhoods in any local base of the identity in  .

.

As in the construction of the completion of a metric space, one can furthermore define the binary relation on Cauchy sequences in  that

that  and

and  are equivalent if for every open neighbourhood

are equivalent if for every open neighbourhood  of the identity in

of the identity in  there exists some number

there exists some number  such that whenever

such that whenever  it follows that

it follows that  . This relation is an equivalence relation: It is reflexive since the sequences are Cauchy sequences. It is symmetric since

. This relation is an equivalence relation: It is reflexive since the sequences are Cauchy sequences. It is symmetric since  which by continuity of the inverse is another open neighbourhood of the identity. It is transitive since

which by continuity of the inverse is another open neighbourhood of the identity. It is transitive since  where

where  and

and  are open neighbourhoods of the identity such that

are open neighbourhoods of the identity such that  ; such pairs exist by the continuity of the group operation.

; such pairs exist by the continuity of the group operation.

In groups

There is also a concept of Cauchy sequence in a group  :

Let

:

Let  be a decreasing sequence of normal subgroups of

be a decreasing sequence of normal subgroups of  of finite index.

Then a sequence

of finite index.

Then a sequence  in

in  is said to be Cauchy (w.r.t.

is said to be Cauchy (w.r.t.  ) if and only if for any

) if and only if for any  there is

there is  such that

such that  .

.

Technically, this is the same thing as a topological group Cauchy sequence for a particular choice of topology on  , namely that for which

, namely that for which  is a local base.

is a local base.

The set  of such Cauchy sequences forms a group (for the componentwise product), and the set

of such Cauchy sequences forms a group (for the componentwise product), and the set  of null sequences (s.th.

of null sequences (s.th.  ) is a normal subgroup of

) is a normal subgroup of  . The factor group

. The factor group  is called the completion of

is called the completion of  with respect to

with respect to  .

.

One can then show that this completion is isomorphic to the inverse limit of the sequence  .

.

An example of this construction, familiar in number theory and algebraic geometry is the construction of the p-adic completion of the integers with respect to a prime p. In this case, G is the integers under addition, and Hr is the additive subgroup consisting of integer multiples of pr.

If  is a cofinal sequence (i.e., any normal subgroup of finite index contains some

is a cofinal sequence (i.e., any normal subgroup of finite index contains some  ), then this completion is canonical in the sense that it is isomorphic to the inverse limit of

), then this completion is canonical in the sense that it is isomorphic to the inverse limit of  , where

, where  varies over all normal subgroups of finite index.

For further details, see ch. I.10 in Lang's "Algebra".

varies over all normal subgroups of finite index.

For further details, see ch. I.10 in Lang's "Algebra".

In constructive mathematics

In constructive mathematics, Cauchy sequences often must be given with a modulus of Cauchy convergence to be useful. If  is a Cauchy sequence in the set

is a Cauchy sequence in the set  , then a modulus of Cauchy convergence for the sequence is a function

, then a modulus of Cauchy convergence for the sequence is a function  from the set of natural numbers to itself, such that

from the set of natural numbers to itself, such that  .

.

Clearly, any sequence with a modulus of Cauchy convergence is a Cauchy sequence. The converse (that every Cauchy sequence has a modulus) follows from the well-ordering property of the natural numbers (let  be the smallest possible

be the smallest possible  in the definition of Cauchy sequence, taking

in the definition of Cauchy sequence, taking  to be

to be  ). However, this well-ordering property does not hold in constructive mathematics (it is equivalent to the principle of excluded middle). On the other hand, this converse also follows (directly) from the principle of dependent choice (in fact, it will follow from the weaker AC00), which is generally accepted by constructive mathematicians. Thus, moduli of Cauchy convergence are needed directly only by constructive mathematicians who (like Fred Richman) do not wish to use any form of choice.

). However, this well-ordering property does not hold in constructive mathematics (it is equivalent to the principle of excluded middle). On the other hand, this converse also follows (directly) from the principle of dependent choice (in fact, it will follow from the weaker AC00), which is generally accepted by constructive mathematicians. Thus, moduli of Cauchy convergence are needed directly only by constructive mathematicians who (like Fred Richman) do not wish to use any form of choice.

That said, using a modulus of Cauchy convergence can simplify both definitions and theorems in constructive analysis. Perhaps even more useful are regular Cauchy sequences, sequences with a given modulus of Cauchy convergence (usually  or

or  ). Any Cauchy sequence with a modulus of Cauchy convergence is equivalent (in the sense used to form the completion of a metric space) to a regular Cauchy sequence; this can be proved without using any form of the axiom of choice. Regular Cauchy sequences were used by Errett Bishop in his Foundations of Constructive Analysis, but they have also been used by Douglas Bridges in a non-constructive textbook (ISBN 978-0-387-98239-7). However, Bridges also works on mathematical constructivism; the concept has not spread far outside of that milieu.

). Any Cauchy sequence with a modulus of Cauchy convergence is equivalent (in the sense used to form the completion of a metric space) to a regular Cauchy sequence; this can be proved without using any form of the axiom of choice. Regular Cauchy sequences were used by Errett Bishop in his Foundations of Constructive Analysis, but they have also been used by Douglas Bridges in a non-constructive textbook (ISBN 978-0-387-98239-7). However, Bridges also works on mathematical constructivism; the concept has not spread far outside of that milieu.

In a hyperreal continuum

A real sequence  has a natural hyperreal extension, defined for hypernatural values H of the index n in addition to the usual natural n. The sequence is Cauchy if and only if for every infinite H and K, the values

has a natural hyperreal extension, defined for hypernatural values H of the index n in addition to the usual natural n. The sequence is Cauchy if and only if for every infinite H and K, the values  and

and  are infinitely close, or adequal, i.e.

are infinitely close, or adequal, i.e.

where "st" is the standard part function.

See also

References

- ↑ Lang, Serge (1993), Algebra (Third ed.), Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., ISBN 978-0-201-55540-0, Zbl 0848.13001

Further reading

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1972). Commutative Algebra (English translation ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-00644-8.

- Lang, Serge (1993), Algebra (Third ed.), Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., ISBN 978-0-201-55540-0, Zbl 0848.13001

- Spivak, Michael (1994). Calculus (3rd ed.). Berkeley, CA: Publish or Perish. ISBN 0-914098-89-6.

- Troelstra, A. S.; D. van Dalen. Constructivism in Mathematics: An Introduction. (for uses in constructive mathematics)

External links

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Fundamental sequence", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4