Cauchy product

In mathematics, more specifically in mathematical analysis, the Cauchy product is the discrete convolution of two infinite series. It is named after the French mathematician Augustin Louis Cauchy.

Definitions

The Cauchy product may apply to infinite series[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11] or power series.[12][13] When people apply it to finite sequences[14] or finite series, it is by abuse of language: they actually refer to discrete convolution.

Convergence issues are discussed in the next section.

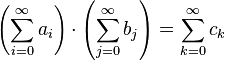

Cauchy product of two infinite series

Let  and

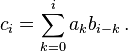

and  be two infinite series with complex terms. The Cauchy product of these two infinite series is defined by a discrete convolution as follows:

be two infinite series with complex terms. The Cauchy product of these two infinite series is defined by a discrete convolution as follows:

where

where  .

.

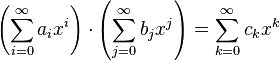

Cauchy product of two power series

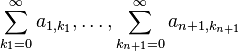

Consider the following two power series

and

and

with complex coefficients  and

and  . The Cauchy product of these two power series is defined by a discrete convolution as follows:

. The Cauchy product of these two power series is defined by a discrete convolution as follows:

where

where  .

.

Convergence and Mertens' theorem

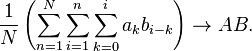

Let (an)n≥0 and (bn)n≥0 be real or complex sequences. It was proved by Franz Mertens that, if the series  converges to A and

converges to A and  converges to B, and at least one of them converges absolutely, then their Cauchy product converges to AB.

converges to B, and at least one of them converges absolutely, then their Cauchy product converges to AB.

It is not sufficient for both series to be convergent; if both sequences are conditionally convergent, the Cauchy product does not have to converge towards the product of the two series, as the following example shows:

Example

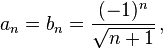

Consider the two alternating series with

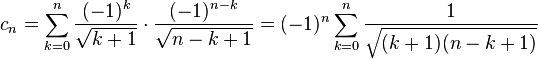

which are only conditionally convergent (the divergence of the series of the absolute values follows from the direct comparison test and the divergence of the harmonic series). The terms of their Cauchy product are given by

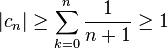

for every integer n ≥ 0. Since for every k ∈ {0, 1, ..., n} we have the inequalities k + 1 ≤ n + 1 and n – k + 1 ≤ n + 1, it follows for the square root in the denominator that √(k + 1)(n − k + 1) ≤ n +1, hence, because there are n + 1 summands,

for every integer n ≥ 0. Therefore, cn does not converge to zero as n → ∞, hence the series of the (cn)n≥0 diverges by the term test.

Proof of Mertens' theorem

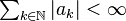

Assume without loss of generality that the series  converges absolutely.

Define the partial sums

converges absolutely.

Define the partial sums

with

Then

by rearrangement, hence

-

(1)

Fix ε > 0. Since  by absolute convergence, and since Bn converges to B as n → ∞, there exists an integer N such that, for all integers n ≥ N,

by absolute convergence, and since Bn converges to B as n → ∞, there exists an integer N such that, for all integers n ≥ N,

-

(2)

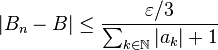

(this is the only place where the absolute convergence is used). Since the series of the (an)n≥0 converges, the individual an must converge to 0 by the term test. Hence there exists an integer M such that, for all integers n ≥ M,

-

(3)

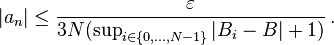

Also, since An converges to A as n → ∞, there exists an integer L such that, for all integers n ≥ L,

-

(4)

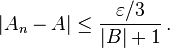

Then, for all integers n ≥ max{L, M + N}, use the representation (1) for Cn, split the sum in two parts, use the triangle inequality for the absolute value, and finally use the three estimates (2), (3) and (4) to show that

By the definition of convergence of a series, Cn → AB as required.

Cesàro's theorem

In cases where the two sequences are convergent but not absolutely convergent, the Cauchy product is still Cesàro summable. Specifically:

If  ,

,  are real sequences with

are real sequences with  and

and  then

then

This can be generalised to the case where the two sequences are not convergent but just Cesàro summable:

Theorem

For  and

and  , suppose the sequence

, suppose the sequence  is

is  summable with sum A and

summable with sum A and  is

is  summable with sum B. Then their Cauchy product is

summable with sum B. Then their Cauchy product is  summable with sum AB.

summable with sum AB.

Examples

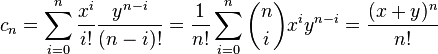

- For some

, let

, let  and

and  . Then

. Then

by definition and the binomial formula. Since, formally,  and

and  , we have shown that

, we have shown that  . Since the limit of the Cauchy product of two absolutely convergent series is equal to the product of the limits of those series, we have proven the formula

. Since the limit of the Cauchy product of two absolutely convergent series is equal to the product of the limits of those series, we have proven the formula  for all

for all  .

.

- As a second example, let

for all

for all  . Then

. Then  for all

for all  so the Cauchy product

so the Cauchy product  does not converge.

does not converge.

Generalizations

All of the foregoing applies to sequences in  (complex numbers). The Cauchy product can be defined for series in the

(complex numbers). The Cauchy product can be defined for series in the  spaces (Euclidean spaces) where multiplication is the inner product. In this case, we have the result that if two series converge absolutely then their Cauchy product converges absolutely to the inner product of the limits.

spaces (Euclidean spaces) where multiplication is the inner product. In this case, we have the result that if two series converge absolutely then their Cauchy product converges absolutely to the inner product of the limits.

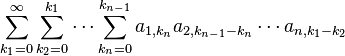

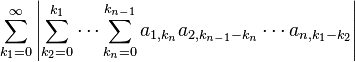

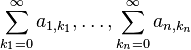

Products of finitely many infinite series

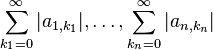

Let  such that

such that  (actually the following is also true for

(actually the following is also true for  but the statement becomes trivial in that case) and let

but the statement becomes trivial in that case) and let  be infinite series with complex coefficients, from which all except the

be infinite series with complex coefficients, from which all except the  th one converge absolutely, and the

th one converge absolutely, and the  th one converges. Then the series

th one converges. Then the series

converges and we have:

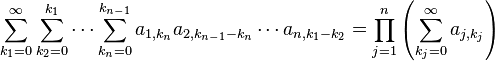

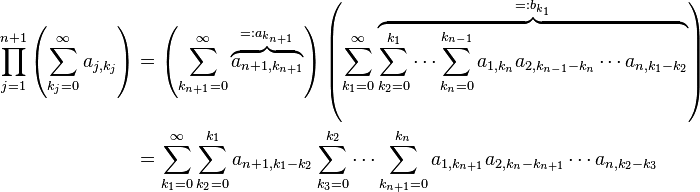

This statement can be proven by induction over  : The case for

: The case for  is identical to the claim about the Cauchy product. This is our induction base.

is identical to the claim about the Cauchy product. This is our induction base.

The induction step goes as follows: Let the claim be true for an  such that

such that  , and let

, and let  be infinite series with complex coefficients, from which all except the

be infinite series with complex coefficients, from which all except the  th one converge absolutely, and the

th one converge absolutely, and the  th one converges. We first apply the induction hypothesis to the series

th one converges. We first apply the induction hypothesis to the series  . We obtain that the series

. We obtain that the series

converges, and hence, by the triangle inequality and the sandwich criterion, the series

converges, and hence the series

converges absolutely. Therefore, by the induction hypothesis, by what Mertens proved, and by renaming of variables, we have:

Therefore, the formula also holds for  .

.

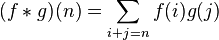

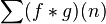

Relation to convolution of functions

A finite sequence can be viewed as an infinite sequence with only finitely many nonzero terms. A finite sequence can be viewed as a function  with finite support. For any complex-valued functions f, g on

with finite support. For any complex-valued functions f, g on  with finite support, one can take the convolution of them:

with finite support, one can take the convolution of them:

.

.

Then  is the same thing as the Cauchy product of

is the same thing as the Cauchy product of  and

and  .

.

More generally, given a unital semigroup S, one can form the semigroup algebra ![\mathbb{C}[S]](../I/m/cdee8b2263c4b649053498034a2b788b.png) of S, with, as usual, the multiplication given by convolution. If one take, for example,

of S, with, as usual, the multiplication given by convolution. If one take, for example,  , then the multiplication on

, then the multiplication on ![\mathbb{C}[S]](../I/m/cdee8b2263c4b649053498034a2b788b.png) is a sort of a generalization of the Cauchy product to higher dimension.

is a sort of a generalization of the Cauchy product to higher dimension.

Notes

- ↑ Canuto & Tabacco 2015, p. 20.

- ↑ Bloch 2011, p. 463.

- ↑ Friedman & Kandel 2011, p. 204.

- ↑ Ghorpade & Limaye 2006, p. 416.

- ↑ Hijab 2011, p. 43.

- ↑ Montesinos, Zizler & Zizler 2015, p. 98.

- ↑ Oberguggenberger & Ostermann 2011, p. 322.

- ↑ Pedersen 2015, p. 210.

- ↑ Ponnusamy 2012, p. 200.

- ↑ Pugh 2015, p. 210.

- ↑ Sohrab 2014, p. 73.

- ↑ Canuto & Tabacco 2015, p. 53.

- ↑ Mathonline, Cauchy Product of Power Series.

- ↑ Weisstein, Cauchy Product.

References

- Apostol, Tom M. (1974), Mathematical Analysis (2nd ed.), Addison Wesley, p. 204, ISBN 978-0-201-00288-1.

- Bloch, Ethan D. (2011), The Real Numbers and Real Analysis, Springer.

- Canuto, Claudio; Tabacco, Anita (2015), Mathematical Analysis II (2nd ed.), Springer.

- Friedman, Menahem; Kandel, Abraham (2011), Calculus Light, Springer.

- Ghorpade, Sudhir R.; Limaye, Balmohan V. (2006), A Course in Calculus and Real Analysis, Springer.

- Hardy, G. H. (1949), Divergent Series, Oxford University Press, p. 227–229.

- Hijab, Omar (2011), Introduction to Calculus and Classical Analysis (3rd ed.), Springer.

- Mathonline, Cauchy Product of Power Series.

- Montesinos, Vicente; Zizler, Peter; Zizler, Václav (2015), An Introduction to Modern Analysis, Springer.

- Oberguggenberger, Michael; Ostermann, Alexander (2011), Analysis for Computer Scientists, Springer.

- Pedersen, Steen (2015), From Calculus to Analysis, Springer.

- Ponnusamy, S. (2012), Foundations of Mathematical Analysis, Birkhäuser.

- Pugh, Charles C. (2015), Real Mathematical Analysis (2nd ed.), Springer.

- Sohrab, Houshang H. (2014), Basic Real Analysis (2nd ed.), Birkhäuser.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Cauchy Product", From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource.