Cauchy–Schwarz inequality

In mathematics, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality is a useful inequality encountered in many different settings, such as linear algebra, analysis, probability theory, vector algebra and other areas. It is considered to be one of the most important inequalities in all of mathematics.[1] It has a number of generalizations, among them Hölder's inequality.

The inequality for sums was published by Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1821), while the corresponding inequality for integrals was first proved by Viktor Bunyakovsky (1859). The modern proof of the integral inequality was given by Hermann Amandus Schwarz (1888).[1]

Statement of the inequality

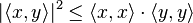

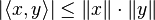

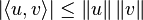

The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality states that for all vectors x and y of an inner product space it is true that

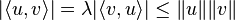

where  is the inner product, also known as dot product. Equivalently, by taking the square root of both sides, and referring to the norms of the vectors, the inequality is written as

is the inner product, also known as dot product. Equivalently, by taking the square root of both sides, and referring to the norms of the vectors, the inequality is written as

Moreover, the two sides are equal if and only if x and y are linearly dependent (or, in a geometrical sense, they are parallel or one of the vector's magnitudes is zero).

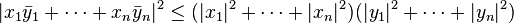

If  and

and  have an imaginary component, the inner product is the standard inner product and the bar notation is used for complex conjugation then the inequality may be restated more explicitly as

have an imaginary component, the inner product is the standard inner product and the bar notation is used for complex conjugation then the inequality may be restated more explicitly as

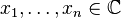

When viewed in this way the numbers x1, ..., xn, and y1, ..., yn are the components of x and y with respect to an orthonormal basis of V.

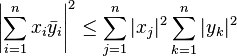

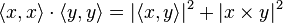

Even more compactly written:

Equality holds if and only if x and y are linearly dependent, that is, one is a scalar multiple of the other (which includes the case when one or both are zero).

The finite-dimensional case of this inequality for real vectors was proven by Cauchy in 1821, and in 1859 Cauchy's student Bunyakovsky noted that by taking limits one can obtain an integral form of Cauchy's inequality. The general result for an inner product space was obtained by Schwarz in the year 1888.

Proof

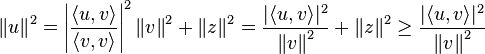

Let u, v be arbitrary vectors in a vector space V over F with an inner product, where F is the field of real or complex numbers. We prove the inequality

and that equality holds only when either u or v is a multiple of the other.

If v = 0 it is clear that we have equality, and in this case u and v are also linearly dependent (regardless of u). We henceforth assume that v is nonzero. We also assume that  otherwise the inequality is obviously true, because neither

otherwise the inequality is obviously true, because neither  nor

nor  can be negative.

can be negative.

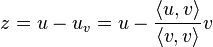

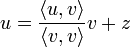

Let

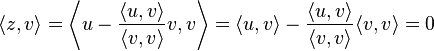

Then, by linearity of the inner product in its first argument, one has

i.e., z is a vector orthogonal to the vector v (Indeed, z is the projection of u onto the plane orthogonal to v.). We can thus apply the Pythagorean theorem to

which gives

and, after multiplication by  , the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

Moreover, if the relation '≥' in the above expression is actually an equality, then

, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

Moreover, if the relation '≥' in the above expression is actually an equality, then  and hence

and hence  ; the definition of z then establishes a relation of linear dependence between u and v. This establishes the theorem.

; the definition of z then establishes a relation of linear dependence between u and v. This establishes the theorem.

Alternative proof

Let u, v be arbitrary vectors in a vector space V over F with an inner product, where F is the field of real or complex numbers.

If  , the theorem holds trivially.

, the theorem holds trivially.

If not, then  ,

,  . Choose

. Choose  . Then

. Then  and

and

It follows that

Special cases

R2 (ordinary two-dimensional space)

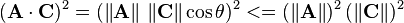

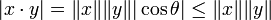

In the usual 2-dimensional space with the dot product, let  and

and  . The Cauchy-Schwarz inequality is that

. The Cauchy-Schwarz inequality is that

where θ is the angle between A and C.

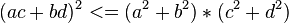

The form above is perhaps the easiest in which to understand the inequality, since the square of the cosine can be at most 1, which occurs when the vectors are in the same or opposite directions. It can, also, be restated in terms of the vector coordinates a, b, c and d as

where equality holds if and only if the vector  is in the same or opposite direction as the vector

is in the same or opposite direction as the vector  , or if one of them is the zero vector.

, or if one of them is the zero vector.

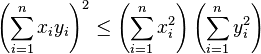

Rn (n-dimensional Euclidean space)

In Euclidean space  with the standard inner product, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality is

with the standard inner product, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality is

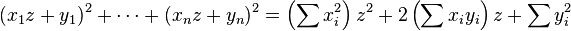

To prove this form of the inequality, consider the following quadratic polynomial in z.

Since it is nonnegative, it has at most one real root in z, whence its discriminant is less than or equal to zero, that is,

which yields the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

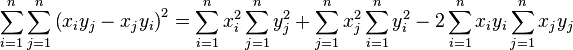

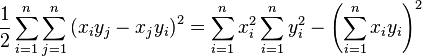

An equivalent proof for  starts with the summation below.

starts with the summation below.

Expanding the brackets we have:

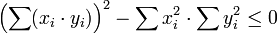

collecting together identical terms (albeit with different summation indices) we find:

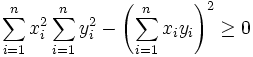

Because the left-hand side of the equation is a sum of the squares of real numbers it is greater than or equal to zero, thus:

Yet another approach when n ≥ 2 (n = 1 is trivial) is to consider the plane containing x and y. More precisely, recoordinatize Rn with any orthonormal basis whose first two vectors span a subspace containing x and y. In this basis only  and

and  are nonzero, and the inequality reduces to the algebra of dot product in the plane, which is related to the angle between two vectors, from which we obtain the inequality:

are nonzero, and the inequality reduces to the algebra of dot product in the plane, which is related to the angle between two vectors, from which we obtain the inequality:

When n = 3 the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality can also be deduced from Lagrange's identity, which takes the form

from which readily follows the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

Another proof of the general case for n can be done by using the technique used to prove Inequality of arithmetic and geometric means.

L2

For the inner product space of square-integrable complex-valued functions, one has

A generalization of this is the Hölder inequality.

Applications

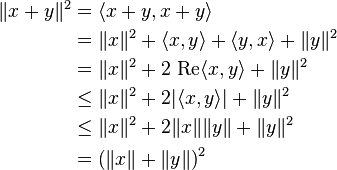

The triangle inequality for the standard norm is often shown as a consequence of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, as follows: given vectors x and y:

Taking square roots gives the triangle inequality.

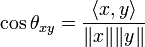

The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality allows one to extend the notion of "angle between two vectors" to any real inner product space, by defining:

The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality proves that this definition is sensible, by showing that the right-hand side lies in the interval [−1, 1], and justifies the notion that (real) Hilbert spaces are simply generalizations of the Euclidean space.

It can also be used to define an angle in complex inner product spaces, by taking the absolute value of the right-hand side, as is done when extracting a metric from quantum fidelity.

The Cauchy–Schwarz is used to prove that the inner product is a continuous function with respect to the topology induced by the inner product itself.

The Cauchy–Schwarz inequality is usually used to show Bessel's inequality.

Probability theory

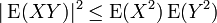

Let X, Y be random variables, then:

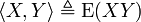

In fact we can define an inner product on the set of random variables using the expectation of their product:

and so, by the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality,

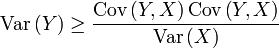

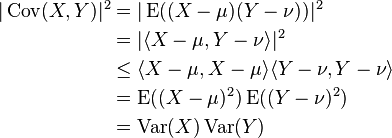

Moreover, if μ = E(X) and ν = E(Y), then

where Var denotes variance and Cov denotes covariance.

Generalizations

Various generalizations of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality exist in the context of operator theory, e.g. for operator-convex functions, and operator algebras, where the domain and/or range of φ are replaced by a C*-algebra or W*-algebra.

This section lists a few of such inequalities from the operator algebra setting, to give a flavor of results of this type.

Positive functionals on C*- and W*-algebras

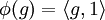

One can discuss inner products as positive functionals. Given a Hilbert space L2(m), m being a finite measure, the inner product < · , · > gives rise to a positive functional φ by

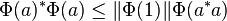

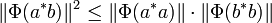

Since < f, f > ≥ 0, φ(f*f) ≥ 0 for all f in L2(m), where f* is pointwise conjugate of f. So φ is positive. Conversely every positive functional φ gives a corresponding inner product < f, g >φ = φ(g*f). In this language, the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality becomes

which extends verbatim to positive functionals on C*-algebras.

We now give an operator theoretic proof for the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality which passes to the C*-algebra setting. One can see from the proof that the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality is a consequence of the positivity and anti-symmetry inner-product axioms.

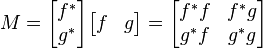

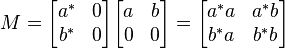

Consider the positive matrix

Since φ is a positive linear map whose range, the complex numbers C, is a commutative C*-algebra, φ is completely positive. Therefore

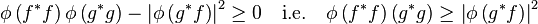

is a positive 2 × 2 scalar matrix, which implies it has positive determinant:

This is precisely the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality. If f and g are elements of a C*-algebra, f* and g* denote their respective adjoints.

We can also deduce from above that every positive linear functional is bounded, corresponding to the fact that the inner product is jointly continuous.

Positive maps

Positive functionals are special cases of positive maps. A linear map Φ between C*-algebras is said to be a positive map if a ≥ 0 implies Φ(a) ≥ 0. It is natural to ask whether inequalities of Schwarz-type exist for positive maps. In this more general setting, usually additional assumptions are needed to obtain such results.

Kadison–Schwarz inequality

The following theorem is named after Richard Kadison.

Theorem. If  is a unital positive map, then for every normal element

is a unital positive map, then for every normal element  in its domain, we have

in its domain, we have  and

and  .

.

This extends the fact  , when

, when  is a linear functional.

is a linear functional.

The case when  is self-adjoint, i.e.

is self-adjoint, i.e.  , is sometimes known as Kadison's inequality.

, is sometimes known as Kadison's inequality.

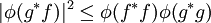

2-positive maps

When Φ is 2-positive, a stronger assumption than merely positive, one has something that looks very similar to the original Cauchy–Schwarz inequality:

Theorem (Modified Schwarz inequality for 2-positive maps).[3] For a 2-positive map Φ between C*-algebras, for all a, b in its domain,

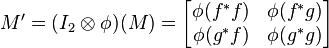

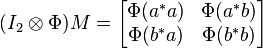

A simple argument for (2) is as follows. Consider the positive matrix

By 2-positivity of Φ,

is positive. The desired inequality then follows from the properties of positive 2 × 2 (operator) matrices.

Part (1) is analogous. One can replace the matrix  by

by  .

.

Physics

The general formulation of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle is derived using the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 The Cauchy–Schwarz Master Class: an Introduction to the Art of Mathematical Inequalities, Ch. 1 by J. Michael Steele.

- ↑ Strang, Gilbert (19 July 2005). "3.2". Linear Algebra and its Applications (4th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0030105678.

- ↑ Paulsen (2002), Completely Bounded Maps and Operator Algebras, ISBN 9780521816694 page 40.

References

J.M. Aldaz, S. Barza, M. Fujii and M.S. Moslehian, Advances in Operator Cauchy--Schwarz inequalities and their reverses, Ann. Funct. Anal. 6 (2015), no. 3, 275--295.

- Bityutskov, V.I. (2001), "Bunyakovskii inequality", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Bouniakowsky, V. (1859), "Sur quelques inegalités concernant les intégrales aux différences finies" (PDF), Mem. Acad. Sci. St. Petersbourg 7 (1): 9

- Cauchy, A. (1821), Oeuvres 2, III, p. 373

- Dragomir, S. S. (2003), "A survey on Cauchy–Bunyakovsky–Schwarz type discrete inequalities", JIPAM. J. Inequal. Pure Appl. Math. 4 (3): 142 pp

- Kadison, R.V. (1952), "A generalized Schwarz inequality and algebraic invariants for operator algebras", Annals of Mathematics 56 (3): 494–503, doi:10.2307/1969657, JSTOR 1969657.

- Lohwater, Arthur (1982), Introduction to Inequalities, Online e-book in PDF fomat

- Paulsen, V. (2003), Completely Bounded Maps and Operator Algebras, Cambridge University Press.

- Schwarz, H. A. (1888), "Über ein Flächen kleinsten Flächeninhalts betreffendes Problem der Variationsrechnung" (PDF), Acta Societatis scientiarum Fennicae XV: 318

- Solomentsev, E.D. (2001), "Cauchy inequality", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4

- Steele, J.M. (2004), The Cauchy–Schwarz Master Class, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-54677-X

External links

- Earliest Uses: The entry on the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality has some historical information.

- Example of application of Cauchy–Schwarz inequality to determine Linearly Independent Vectors Tutorial and Interactive program.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||