European wars of religion

The European wars of religion were a series of religious wars waged in Europe from ca. 1524 to 1648, following the onset of the Protestant Reformation in Central, Western and Northern Europe. Although sometimes unconnected, all of these wars were strongly influenced by the religious change of the period, and the conflict and rivalry that it produced. This is not to say that the combatants can be neatly categorised by religion or were divided by their religion alone, as this was often not the case.

Individual conflicts that can be distinguished within this topic include:

- Conflicts immediately connected with the Reformation of the 1520s to 1540s:

- The German Peasants' War (1524–1525)

- The battle of Kappel in Switzerland (1531)

- The Schmalkaldic War (1546–1547) in the Holy Roman Empire

- The Eighty Years' War (1568–1648) in the Low Countries

- The French Wars of Religion (1562–1598)

- The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), affecting the Holy Roman Empire including Habsburg Austria and Bohemia, France, Denmark and Sweden

- The Wars of the Three Kingdoms (1639–1651), affecting England, Scotland and Ireland

Although later wars such as the Nine Years' War (1688–97) had a religious component that was important locally in some arenas, they were more fundamentally undertaken for political reasons, with coalitions forming across religious divisions. Purely political motivations and cross-religious alliances were also significant in many of the earlier wars.

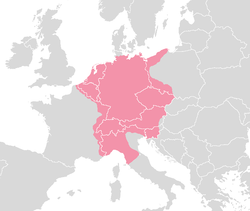

The Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, encompassing present-day Germany and portions of neighbouring lands, was the single area most devastated by the Wars of Religion. The Empire was a fragmented collection of semi-independent states with an elected Holy Roman Emperor as its head; after the 14th century, this position was usually held by a Habsburg. The Austrian House of Habsburg was a major European power in its own right, ruling over some eight million subjects in present day Germany, Austria, Bohemia and Hungary. The Empire also contained regional powers, such as Bavaria, the Electorate of Saxony, the Margraviate of Brandenburg, the Electorate of the Palatinate, the Landgraviate of Hesse, the Archbishopric of Trier, and Württemberg. A vast number of minor independent duchies, free imperial cities, abbeys, bishoprics, and small lordships of sovereign families rounded out the Empire.

Lutheranism, from its inception at Wittenberg in 1519, found a ready reception in Germany, as well as in formerly Hussite Bohemia. The preaching of Martin Luther and his many followers raised tensions across Europe.

In Northern Germany, Luther adopted the stratagem of gaining the support of the local princes in his struggle to take over and re-establish the church along Lutheran lines. The Elector of Saxony, the Landgrave of Hesse and other North German princes not only protected Luther from retaliation from the edict of outlawry issued by the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, but also used state power to enforce the establishment of Lutheran worship in their lands. Church property was seized and Catholic worship was forbidden in most lands which adopted the Lutheran Reformation. The political conflicts thus engendered within the Empire led almost inevitably to war.

The Radicals

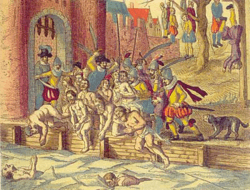

The first large-scale violence was engendered by the more radical of Luther's followers, who wished to extend wholesale reform of the Church to a similar wholesale reform of society in general. This was a step which the princes who supported Luther were in no way willing to countenance. The German Peasants' War of 1524/1525 was a popular revolt inspired by the teachings of the radical reformers. It consisted of a series of economic as well as religious revolts by peasants, townsfolk and nobles. The conflict took place mostly in southern, western and central areas of modern Germany but also affected areas in neighboring modern Switzerland and Austria. At its height, in the spring and summer of 1525, it involved an estimated 300,000 peasant insurgents. Contemporary estimates put the dead at 100,000. It was Europe's largest and most widespread popular uprising before the 1789 French Revolution.

Because of their revolutionary political ideas, radical reformers like Thomas Müntzer were compelled to leave the Lutheran cities of North Germany in the early 1520s. They spread their revolutionary religious and political doctrines into the countryside of Bohemia, Southern Germany, and Switzerland. Starting as a revolt against feudal oppression, the peasants' uprising became a war against all constituted authorities, and an attempt to establish by force an ideal Christian commonwealth, with absolute equality and the community of goods. The total defeat of the insurgents at Frankenhausen (May 15, 1525), was followed by the execution of Müntzer and thousands of peasant followers. Martin Luther rejected the demands of the insurgents and upheld the right of Germany's rulers to suppress the uprisings. This played a major part in the rejection of his teachings by many German peasants, particularly in the south.

After the Peasants' War (1524/25), a second and more determined attempt to establish a theocracy was made at Münster, in Westphalia (1532–1535). Here a group of prominent citizens, including the Lutheran pastor Bernhard Rothmann, Jan Matthys, and Jan Bockelson ("John of Leiden") had little difficulty in obtaining possession of the town on January 5, 1534. Matthys identified Münster as the "New Jerusalem", and preparations were made, not only to hold what had been gained, but to proceed from Münster toward the conquest of the world.

Claiming to be the successor of David, John of Leiden was installed as king, legalized polygamy, and himself took sixteen wives, one of whom he beheaded himself in the marketplace. Community of goods was also established. After obstinate resistance, the town was taken by the besiegers on June 24, 1535, and then Leiden and some of his more prominent followers were executed in the marketplace.

The Schmalkaldic Wars

.jpg)

Following the Diet of Augsburg in 1530, the Emperor demanded that all religious innovations not authorised by the Diet be abandoned by 15 April 1531. Failure to comply would result in prosecution by the Imperial Court. In response, the Lutheran princes who had set up Protestant churches in their own realms met in the town of Schmalkalden in December 1530. Here they banded together to form the Schmalkaldic League (German: Schmalkaldischer Bund), an alliance designed to protect themselves from Imperial action. Its members eventually intended the League to replace the Holy Roman Empire itself, and each state was to provide 10,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry for mutual defence. In 1532 the Emperor, pressed by external troubles, stepped back from confrontation, offering the "Peace of Nuremberg", which suspended all action against the Protestant states pending a General Council of the Church. The moratorium kept peace in the German lands for over a decade. However this was a decade in which Protestantism was able to entrench its position in the lands that it already occupied. And it was also able to spread.

The peace finally ended in the Schmalkaldic War (German: Schmalkaldischer Krieg), a brief conflict between 1546 and 1547 between the forces of Charles V and the princes of the Schmalkaldic League. The conflict was to the advantage of the Catholics, and the Emperor was able to impose the Augsburg Interim, a compromise allowing slightly modified worship, and supposed to remain in force until the conclusion of a General Council of the Church. However various Protestant elements rejected the Interim, and the Second Schmalkaldic war broke out in 1552.

The Peace of Augsburg (1555), signed by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, confirmed the result of the 1526 Diet of Speyer and ended the violence between the Lutherans and the Catholics in Germany. It stated that:

- German princes (numbering 225) could choose the religion (Lutheranism or Catholicism) of their realms according to their conscience. The citizens of each state were forced to adopt the religion of their rulers (the principle of cuius regio, eius religio).

- Lutherans living in an ecclesiastical state (under the control of a bishop) could continue to practice their faith.

- Lutherans could keep the territory that they had captured from the Catholic Church since the Peace of Passau in 1552.

- The ecclesiastical leaders of the Catholic Church (bishops) that had converted to Lutheranism were required to give up their territories.

Religious tensions remained strong throughout the second half of the 16th century. The Peace of Augsburg began to unravel as some bishops converting to Protestantism refused to give up their bishoprics. This was evident from the Cologne War (1582–83), a conflict initiated when the prince-archbishop of the city converted to Calvinism. Religious tensions also broke into violence in the German free city of Donauwörth in 1606 when the Lutheran majority barred the Catholic residents from holding a procession, provoking a riot. This prompted intervention by Duke Maximilian of Bavaria on behalf of the Catholics.

By the end of the 16th century the Rhine lands and those of southern Germany remained largely Catholic, while Lutherans predominated in the north, and Calvinists dominated in west-central Germany, Switzerland and the Netherlands. The latter formed the League of Evangelical Union in 1608.

The Thirty Years' War

By 1617 Germany was bitterly divided, and it was clear that Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia, would die without an heir. His lands would therefore fall to his nearest male relative, his cousin Ferdinand of Styria. Ferdinand, having been educated by the Jesuits, was a staunch Catholic. The rejection of Ferdinand as Crown Prince by primarily Hussite Bohemia, triggered the Thirty Years' War in 1618 when his representatives were defenestrated in Prague.

The Thirty Years' War was fought between 1618 and 1648, principally on the territory of today's Germany, and involved most of the major European powers. Beginning as a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire, it gradually developed into a general war involving much of Europe, for reasons not necessarily related to religion. The war marked a continuation of the France-Habsburg rivalry for pre-eminence in Europe, which led later to direct war between France and Spain. Military intervention by external powers such as Denmark and Sweden on the Protestant side increased the duration of the war and the extent of its devastation. In the latter stages of the war, Catholic France, fearful of an increase in Habsburg power, also intervened on the Protestant side.

The major impact of the Thirty Years' War, in which mercenary armies were extensively used, was the devastation of entire regions scavenged bare by the foraging armies. Episodes of widespread famine and disease devastated the population of the German states and, to a lesser extent, the Low Countries and Italy, while bankrupting many of the powers involved. The war ended with the Treaty of Münster, a part of the wider Peace of Westphalia.

During the war, Germany's population was reduced by 30% on average. In the territory of Brandenburg, the losses had amounted to half, while in some areas an estimated two thirds of the population died. The population of the Czech lands declined by a third. The Swedish armies alone destroyed 2,000 castles, 18,000 villages and 1,500 towns in Germany, one-third of all German towns. Huge damage was done to monasteries, churches and other religious institutions. The war had proved disastrous for the German "Holy Roman Empire". Germany lost population and territory, and was henceforth divided into hundreds of largely impotent semi-independent states. The Imperial power retreated to Austria and the Habsburg lands. The Netherlands and Switzerland were confirmed in independence. The peace institutionalised the Catholic, Lutheran, Calvinist religious divide in Germany, with populations either converting, or moving to areas controlled by rulers of their own faith.

Low Countries

The Low Countries have a particular history of religious conflict which had its roots in the Calvinist reformation movement of the 1530s. These conflicts became known as the Dutch Revolt or the Eighty Years' War. By dynastic inheritance the whole of the Netherlands, (the modern day Netherlands and Belgium) had come to be ruled by the kings of Spain. Following aggressive Calvinist preaching in and around the rich merchant cities of the southern Netherlands, organized anti-catholic religious protests grew in violence and frequency. In 1566, a league of about 400 members of the high nobility, themselves disgruntled at Spanish rule, presented a petition to the governor Margaret of Parma, to suspend punitive actions against the Calvinists.

In early August 1566, a mob stormed the church of Hondschoote in Flanders (now in Northern France).[1] This relatively small incident spread North and led to the Beeldenstorm, a massive iconoclastic movement by Calvinists, who stormed churches and other religious buildings to desecrate and destroy statues and images of Catholic saints all over the Netherlands. According to the Calvinists, these statues represented worship of idols. The number of actual image-breakers appears to have been relatively small. Limm (1989) notes that "there were few cases of more than 200 people being involved at any one time" even in the northern provinces, where large crowds often attended these iconoclastic events. In the case of the southern provinces, he speaks of a relatively small, orderly group moving along the country. Spaans (1999) argues that iconoclasm was actually organized by local elites for political reasons[2] In general, local authorities did not step in to rein in the vandalism. The actions of the iconoclasts drove the nobility into two camps, with William of Orange and other grandees supporting the iconoclasts, and others, notably Henry of Brederode, opposing them.

In 1568, William returned to try to drive the highly unpopular Duke of Alba from Brussels. A co-ordinated Protestant attempt was made to take over the Netherlands from four different directions, with armies led by William's brothers invading from Germany and French Huguenots invading from the south. The Battle of Rheindalen near Roermond occurred on 23 April 1568 and was won by the Spanish, but the Battle of Heiligerlee, fought on 23 May 1568, resulted in a victory for the rebel army. However the rebel campaign ended in failure as William ran out of money to pay his army and his allies were destroyed by Alba.

In its battle to maintain Catholic control of the Low Countries, Spain was severely hampered by the fact that it was also fighting a war against the Ottoman Empire in the Mediterranean. Even so, by 1570 the Spanish had mostly suppressed the rebellion throughout the Netherlands. However, on April 1, 1572, Dutch Calvinist raiders, known as Sea Beggars, forced from sanctuary in England, unexpectedly captured the almost undefended northern Netherlands town of Brielle. Most of the important cities in the provinces of Holland and Zeeland immediately declared loyalty to the rebels. Notable exceptions were Amsterdam and Middelburg, which remained loyal to the Catholic cause until capture in 1578. William of Orange was put at the head of the revolt, entering the Netherlands with an army 20,000 strong, and with forces of French Huguenots in support.

Division

The new revolt led to increasing discord amongst the Dutch. On one side was a militant Calvinist minority that wanted to continue fighting the Catholic King Philip II, and convert all Dutch citizens to Calvinism. On the other was a minority of Catholics that wanted to remain loyal to the Landholder (Dutch: landvoogd) and the Spanish-backed government below him. In between was the majority of historically Catholic citizens who had no particular allegiance, but shared a desire to restore Dutch privileges and to get rid of the Spanish mercenary armies. Alba was replaced in 1573 by Luis de Requesens and a new policy of moderation was attempted. However Spain's inability to pay its mercenary armies led to numerous mutinies and in November 1576 troops sacked Antwerp at the cost of some 8,000 lives. This so-called "Spanish Fury" strengthened the resolve of the rebels in the seventeen provinces. William of Orange took advantage of the anarchy to establish wider control of virtually the whole Netherlands in alliance with the States-General, entering Brussels in September 1577.

On January 6, 1579, upset by Calvinist outrages in Oudenarde, Kortrijk, Bruges and Ieper, and the continued aggressive Calvinism of the Northern States, some of the Southern States signed the Union of Arras (Atrecht), declaring their loyalty to the Spanish king. In response, William united the northern states of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders and the province of Groningen in the Union of Utrecht on January 23, 1579. Some southern cities like Bruges, Ghent, Brussels and Antwerp joined the Union of Utrecht, and effectively, the 17 provinces were now divided into two warring states.

Over the following years, the new Spanish governor Alexander Farnese (Duke of Parma) reconquered the major part of Flanders and Brabant, as well as large parts of the northeastern provinces. The Roman Catholic religion was restored in much of this area. In 1585, Antwerp—the largest city in the Low Countries at the time—fell into his hands, which caused over half its population to flee to the north (see also Siege of Antwerp).

The Netherlands were split into an independent northern part, while the southern part remained under Spanish control. Due to the almost uninterrupted rule of the Calvinist-dominated separatists, most of the population of the northern provinces became converted to Protestantism over the next decades. The south, under Spanish rule, remained a Catholic stronghold; most of its Protestants fled to the north. Spain retained a large military presence in the south, where it could also be used against France. After a period of peace, war took up again in 1622, to be finally ended on January 30, 1648, with the Treaty of Münster between Spain and the independent Netherlands. This treaty was part of the European scale Peace of Westphalia that also ended the Thirty Years' War.

Swiss Confederacy

In 1529 under the lead of Huldrych Zwingli, the Protestant canton and city of Zürich had concluded with other Protestant cantons a defence alliance, the Christliches Burgrecht, which also included the cities of Konstanz and Strasbourg. The Catholic cantons in response had formed an alliance with Ferdinand of Austria.

After numerous minor incidents and provocations from both sides, a Catholic priest was executed in the Thurgau in May 1528, and the Protestant pastor J. Keyser was burned at the stake in Schwyz in 1529. The last straw was the installation of a Catholic reeve at Baden, and Zürich declared war on 8 June, occupied the Thurgau and the territories of the Abbey of St. Gall and marched to Kappel at the border to Zug. Open war was avoided by means of a peace agreement (Erster Landfriede), that was not exactly favourable to the Catholic side, who had to dissolve its alliance with the Austrian Habsburgs. The tensions remained essentially unresolved, and would flare high again in the second war of Kappel two years later.

On October 11, 1531, the Catholic cantons decisively defeated the forces of Zürich in the Battle of Kappel. The Zürich troops had little support from allied Protestant cantons, and Huldrych Zwingli was killed on the battlefield, along with twenty-four other pastors.

After the defeat, the forces of Zürich regrouped and attempted to occupy the Zugerberg, and some of them camped on the Gubel hill near Menzingen. A small force of Aegeri succeeded in routing the camp, and the demoralized Zürich force had to retreat, forcing the Protestants to agree to a peace treaty to their disadvantage. Switzerland was to be divided into a patchwork of Protestant and Catholic cantons, with the Protestants tending to dominate the larger cities, and the Catholics the more rural areas.

In 1656, tensions between Protestants and Catholics re-emerged and led to the outbreak of the First War of Villmergen. The Catholics were victorious and able to maintain their political dominance.

France

As early as 1532, King François I, and (in 1551), King Henry II, had intervened politically and militarily in support of the Protestant German princes against the Habsburgs. However both kings firmly repressed attempts to spread Lutheran ideas within France. An organised influx of Calvinist preachers from Geneva and elsewhere during the 1550s, succeeded in setting up hundreds of underground Calvinist congregations in France.

The 1560s

In a pattern soon to become familiar in the Netherlands and Scotland, underground Calvinist preaching, and the formation of covert alliances with members of the nobility quickly led to more direct action to gain political and religious control. The prospect of taking over rich church properties and monastic lands had led nobles in many parts of Europe to support a "princely" Reformation. Added to this was the newer, Calvinist, teaching that the leading citizens had the duty to overthrow an "ungodly" ruler (i.e. one who was not supportive of Calvinism.) In March 1560, the "Amboise conspiracy", or "Tumult of Amboise", was an attempt on the part of a group of disaffected nobles to abduct the young king Francis II and eliminate the Catholic House of Guise. It was foiled when their plans were discovered. The first major instances of systematic Protestant destruction of images and statues in Catholic churches occurred in Rouen and La Rochelle in 1560. The following year, the attacks extended to over 20 cities and towns, and would, in turn, incite Catholic urban groups to massacres and riots in Sens, Cahors, Carcassonne, Tours and other cities.[3]

In December 1560, Francis II died and Catherine de' Medici became regent for her young son Charles IX. Although a Roman Catholic, she was prepared to deal favourably with the Huguenot House of Bourbon. She therefore supported religious toleration in the shape of the Edict of Saint-Germain (January 1562), which allowed the Huguenots to worship publicly outside of towns and privately inside of them. On March 1, however, a faction of the Guise family's retainers attacked an illegal Calvinist service in Wassy-sur-Blaise in Champagne. As hostilities broke out, the Edict was revoked.

This provoked the First War. The Bourbons, with English support, and led by Louis I de Bourbon, Prince de Condé, and Admiral Coligny began to seize and garrison strategic towns along the Loire. The Battle of Dreux and the battle of Orléans, were the first major engagements of the conflict. In February 1563, at Orléans, Francis, Duke of Guise was assassinated, and Catherine's fears that the war might drag on led her to mediate a truce and the Edict of Amboise (1563), which again provided for a controlled religious toleration of Protestant worship.

However this was generally regarded as unsatisfactory by both Catholics and Protestants. The political temperature of the surrounding lands was rising, as religious unrest grew in the Netherlands. The Huguenots tried to gain French government support for intervention against the Spanish forces arriving in the Netherlands. Failing this, Protestant troops then made an unsuccessful attempt to capture and take control of King Charles IX at Meaux in 1567. This provoked a further outbreak of hostilities (the Second War) which ended in another unsatisfactory truce, the Peace of Longjumeau (March 1568).

In September of that year, war again broke out (the Third War). Catherine and Charles decided this time to ally themselves with the House of Guise. The Huguenot army was under the command of Louis I de Bourbon, prince de Condé and aided by forces from south-eastern France and a contingent of Protestant militias from Germany—including 14,000 mercenary reiters led by the Calvinist Duke of Zweibrücken.[4] After the Duke was killed in action, he was succeeded by the Count of Mansfeld and the Dutch William of Orange and his brothers Louis and Henry. Much of the Huguenots' financing came from Queen Elizabeth of England. The Catholics were commanded by the Duke d'Anjou (later King Henry III) and assisted by troops from Spain, the Papal States and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany.[5]

The Protestant army laid siege to several cities in the Poitou and Saintonge regions (to protect La Rochelle), and then Angoulême and Cognac. At the Battle of Jarnac (16 March 1569), the Prince de Condé was killed, forcing Admiral de Coligny to take command of the Protestant forces. Coligny and his troops retreated to the south-west and regrouped with Gabriel, comte de Montgomery, and in spring of 1570 they pillaged Toulouse, cut a path through the south of France and went up the Rhone valley up to La Charité-sur-Loire. The staggering royal debt and Charles IX's desire to seek a peaceful solution[6] led to the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (8 August 1570), which once more allowed some concessions to the Huguenots. In 1572, rising tensions between local Catholics and Protestant forces attending the wedding of the Protestant Henry of Navarre, and the King's sister, Marguerite de Valois, culminated in the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre. This led to the Fourth and Fifth Civil wars in 1572 and 1573-1576.

Henry III

Henry of Anjou was crowned King Henry III of France in 1575, at Rheims, but hostilities—the Fifth War—had already flared up again.

Henry soon found himself in the difficult position of trying to maintain royal authority in the face of feuding warlords who refused to compromise. In 1576, the King signed the Edict of Beaulieu, granting minor concessions to the Calvinists, but a brief Sixth Civil War took place in 1577. Henry I, Duke of Guise, formed the Catholic League to protect the Catholic cause in France. Further hostilities—the Seventh War (1579–1580)—ended in the stalemate of the Treaty of Fleix.

The fragile compromise came to an end in 1584, when the King's youngest brother and heir presumptive, François, Duke of Anjou, died. As Henry III had no son, under Salic Law, the next heir to the throne was the Calvinist Prince Henri of Navarre. Under pressure from the Duke of Guise, Henri III reluctantly issued an edict suppressing Protestantism and annulling Henri of Navarre's right to the throne.

In December 1584, the Duke of Guise signed the Treaty of Joinville on behalf of the Catholic League with Philip II of Spain, who supplied a considerable annual grant to the League. The situation degenerated into the Eighth War (1585–1589). Henry of Navarre again sought foreign aid from the German princes and Elizabeth I of England. Meanwhile, the solidly Catholic people of Paris, under the influence of the Committee of Sixteen were becoming dissatisfied with Henry III and his failure to defeat the Calvinists. On 12 May 1588, a popular uprising raised barricades on the streets of Paris, and Henry III fled the city. The Committee of Sixteen took complete control of the government and welcomed the Duke of Guise to Paris. The Guises then proposed a settlement with a cipher as heir and demanded a meeting of the Estates-General, which was to be held in Blois.

King Henri decided to strike first. On December 23, 1588, at the Château de Blois, Henry of Guise and his brother, the Cardinal de Guise, were lured into a trap and were murdered. The Duke of Guise had been highly popular in France, and the league declared open war against King Henry. The Parlement of Paris instituted criminal charges against the King, who now joined forces with his cousin, Henry of Navarre, to war against the League.

Charles of Lorraine, Duke of Mayenne, then became the leader of the Catholic League. League presses began printing anti-royalist tracts under a variety of pseudonyms, while the Sorbonne proclaimed that it was just and necessary to depose Henri III. In July 1589, in the royal camp at Saint-Cloud, a monk named Jacques Clément gained an audience with the King and drove a long knife into his spleen. Clément was executed on the spot, taking with him the information of who, if anyone, had hired him. On his deathbed, Henri III called for Henry of Navarre, and begged him, in the name of Statecraft, to become a Catholic, citing the brutal warfare that would ensue if he refused. In keeping with Salic Law, he named Henri as his heir.

Henry IV

The situation on the ground in 1589 was that King Henry IV of France, as Navarre had become, held the south and west, and the Catholic League the north and east. The leadership of the Catholic League had devolved to the Duke de Mayenne, who was appointed Lieutenant-General of the kingdom. He and his troops controlled most of rural Normandy. However, in September 1589, Henry inflicted a severe defeat on the Duke at the Battle of Arques. Henry's army swept through Normandy, taking town after town throughout the winter.

The King knew that he had to take Paris if he stood any chance of ruling all of France. This, however, was no easy task. The Catholic League's presses and supporters continued to spread stories about atrocities committed against Catholic priests and the laity in Protestant England (see Forty Martyrs of England and Wales). The city prepared to fight to the death rather than accept a Calvinist king. The Battle of Ivry, fought on March 14, 1590, was another victory for the king, and Henry's forces went on to lay siege to Paris, but the siege was broken by Spanish support. Realising that his predecessor had been right and that there was no prospect of a Protestant king succeeding in Catholic Paris, Henry reputedly uttered the famous phrase Paris vaut bien une messe (Paris is well worth a mass). He was formally received into the Roman Catholic Church in 1593 and was crowned at Chartres in 1594.

Some members of the League fought on, but enough Catholics were won over by the King's conversion to increasingly isolate the diehards. The Spanish withdrew from France under the terms of the Peace of Vervins. Henry was faced with the task of rebuilding a shattered and impoverished Kingdom and reuniting France under a single authority. The wars concluded with the issuing of the Edict of Nantes by Henry IV of France, which granted a degree of religious toleration to Protestants.

France, although always ruled by a Catholic monarch, had played a major part in supporting the Protestants in Germany and the Netherlands against their dynastic rivals, the Habsburgs. The period of the French Wars of Religion effectively removed France's influence as a major European power, allowing the Catholic forces in the Holy Roman Empire to regroup and recover.

Great Britain and Ireland

The Reformation came to Britain and Ireland with King Henry VIII of England's breach with the Catholic Church in 1533. At this time there were only a limited number of Protestants among the general population, and these were mostly living in the towns of the South and the East of England. With the state-ordered break with the Pope in Rome, the Church in England, Wales and Ireland was placed under the rule of the King and Parliament.

The first major changes to doctrine and practice took place under Vicar-General Thomas Cromwell, and the newly appointed Protestant-leaning Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. The first challenge to the institution of these reforms came from Ireland, where 'Silken' Thomas Fitzgerald cited the controversy to justify his armed uprising of 1534. The young Fitzgerald failed to gain much local support however, and October saw a 1,600 strong army of English and Welshmen arrive in Ireland, along with four modern siege-guns.[7] The following year Fitzgerald was blasted into submission, and in August he was induced to surrender.

Shortly after this episode, local resistance to the reforms emerged in England. The Dissolution of the Monasteries, which began in 1536, provoked a violent northern Catholic rebellion in the Pilgrimage of Grace, which was eventually put down with much bloodshed. The reformation continued to be imposed on an often unwilling population with the aid of stern laws that made it treason, punishable by death, to oppose the King's actions with respect to religion. The next major armed resistance took place in the Prayer Book Rebellion of 1549, which was an unsuccessful rising in western England against the enforced substitution of Cranmer's English language service for the Latin Catholic Mass.

Following the restoration of Catholicism under Queen Mary I of England in 1553, there was a brief unsuccessful Protestant rising in the south-east of England.

Scottish Reformation

The Reformation in Scotland began in conflict. Fiery Calvinist preacher John Knox returned to Scotland in 1560, having been exiled for his part in the assassination of Cardinal Beaton. He proceeded to Dundee where a large number of Protestant sympathisers and noblemen had gathered. Knox was declared an outlaw by the Queen Regent, Mary of Guise, but the Protestants went at once to Perth, a walled town that could be defended in case of a siege. At the church of St John the Baptist, Knox preached a fiery sermon which provoked an iconoclastic riot. A mob poured into the church and it was entirely gutted. In the pattern of Calvinist riots in France and the Netherlands, the mob then attacked two friaries in the town, looting their gold and silver and smashing images. Mary of Guise gathered those nobles loyal to her and a small French army.

However, with Protestant reinforcements arriving from neighbouring counties, the queen regent retreated to Dunbar. By now Calvinist mobs had overrun much of central Scotland, destroying monasteries and catholic churches as they went. On 30 June, the Protestants occupied Edinburgh, though they were only able to hold it for a month. But even before their arrival, the mob had already sacked the churches and the friaries. On 1 July, Knox preached from the pulpit of St Giles', the most influential in the capital.[8]

Knox negotiated by letter with William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, Elizabeth's chief advisor, for English support. When additional French troops arrived in Leith, Edinburgh's seaport, the Protestants responded by retaking Edinburgh. This time, on 24 October 1559, the Scottish nobility formally deposed Mary of Guise from the regency. Her secretary, William Maitland of Lethington, defected to the Protestant side, bringing his administrative skills. For the final stage of the revolution, Maitland appealed to Scottish patriotism to fight French domination. Support from England finally arrived and by the end of March, a significant English army joined the Scottish Protestant forces. The sudden death of Mary of Guise in Edinburgh Castle on 10 June 1560 paved the way for the signing of the Treaty of Edinburgh, and the withdrawal of French and English troops from Scotland, leaving the Scottish Calvinists in control on the ground. Catholicism was forcibly suppressed.

The return of Mary, Queen of Scots, to Scotland in 1560, led to further tension between her and the Protestant Lords of the Congregation. Mary claimed to favour religious toleration on the French model, however the Protestant establishment feared a reestablishment of Catholicism, and sought with English help to neutralise or depose Mary. Mary's marriage to a leading Catholic, precipitated Mary's half-brother, the Earl of Moray, to join with other Protestant Lords in open rebellion. Mary set out for Stirling on 26 August 1565 to confront them. Moray and the rebellious lords were routed and fled into exile, the decisive military action becoming known as the Chaseabout Raid. In 1567, however, Mary was captured by another rebellious force at the Carberry Hill and imprisoned in Loch Leven Castle, where she was forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in favour of her one-year-old son James. Mary escaped from Loch Leven the following year, and once again managed to raise a small army. After her army's defeat at the Battle of Langside on May 13, she fled to England, where she was imprisoned by Queen Elizabeth. Her son James VI was raised as a Protestant, later becoming King of England as well as Scotland.

English Civil War

England, Scotland and Ireland, in personal union under the Stuart king, James I & VI, continued Elizabeth I's policy of providing military support to European Protestants in the Netherlands and France. King Charles I decided to send an expeditionary force to relieve the French Huguenots whom Royal French forces held besieged in La Rochelle. However tax-raising authority for these wars was getting harder and harder to raise from parliament.

In 1638 the Scottish National Covenant was signed by aggrieved presbyterian lords and commoners. A Scottish rebellion, known as the Bishops War soon followed, leading to the defeat of a weak royalist counter-force in 1640. The rebels went on to capture Newcastle upon Tyne, further weakening King Charles' authority.

In October 1641, a major rebellion broke out in Ireland. Charles soon needed to raise more money to suppress this Irish Rebellion. Meanwhile English Puritans and Scottish Calvinists intensely opposed the king's main religious policy of unifying the Church of England and the Church of Scotland under a form of High Church Anglicanism. This, its opponents believed, was far too catholic in form, and based on the authority of bishops.

The English parliament refused to vote enough money for Charles to defeat the Scots without the King giving up much of his authority and reforming the English church along more Calvinist lines. This the king refused, and deteriorating relations led to the out break of war in 1642. The first pitched battle of the war, fought at Edgehill on 23 October 1642, proved inconclusive, and both the Royalists and Parliamentarians claimed it as a victory. The second field action of the war, the stand-off at Turnham Green, saw Charles forced to withdraw to Oxford. This city would serve as his base for the remainder of the war.

In general, the early part of the war went well for the Royalists. The turning-point came in the late summer and early autumn of 1643, when the Earl of Essex's army forced the king to raise the siege of Gloucester and then brushed the Royalist army aside at the First Battle of Newbury on 20 September 1643. In an attempt to gain an advantage in numbers Charles negotiated a ceasefire with the Catholic rebels in Ireland, freeing up English troops to fight on the Royalist side in England. Simultaneously Parliament offered concessions to the Scots in return for their aid and assistance.

With the help of the Scots, Parliament won at Marston Moor (2 July 1644), gaining York and much of the north of England. Oliver Cromwell's conduct in this battle proved decisive, and demonstrated his leadership potential. In 1645 Parliament passed the Self-denying Ordinance, by which all members of either House of Parliament laid down their commands, allowing the re-organization of its main forces into the New Model Army. By 1646 Charles had been forced to surrender himself to the Scots and the parliamentary forces were in control of England. Charles was executed in 1649, and the monarchy was not restored until 1660. Even then, religious strife continued through the Glorious Revolution and even thereafter.

Ireland

Ireland had known continuous war since the rebellion of 1641, with most of the island controlled by the Irish Confederates. Increasingly threatened by the armies of the English Parliament after Charles I's arrest in 1648, the Confederates signed a treaty of alliance with the English Royalists. The joint Royalist and Confederate forces under the Duke of Ormonde attempted to eliminate the Parliamentary army holding Dublin, but their opponents routed them at the Battle of Rathmines (2 August 1649). As the former Member of Parliament Admiral Robert Blake blockaded Prince Rupert's fleet in Kinsale, Oliver Cromwell could land at Dublin on 15 August 1649 with an army to quell the Royalist alliance in Ireland.

Cromwell's suppression of the Royalists in Ireland during 1649 still has a strong resonance for many Irish people. After the siege of Drogheda, the massacre of nearly 3,500 people—comprising around 2,700 Royalist soldiers and all the men in the town carrying arms, including civilians, prisoners, and Catholic priests—became one of the historical memories that has driven Irish-English and Catholic-Protestant strife during the last three centuries. However, the massacre has significance mainly as a symbol of the Irish perception of Cromwellian cruelty, as far more people died in the subsequent guerrilla and scorched-earth fighting in the country than at infamous massacres such as Drogheda and Wexford. The Parliamentarian conquest of Ireland ground on for another four years until 1653, when the last Irish Confederate and Royalist troops surrendered. Historians have estimated that up to 30% of Ireland's population either died or had gone into exile by the end of the wars. The victors confiscated almost all Irish Catholic-owned land in the wake of the conquest and distributed it to the Parliament's creditors, to the Parliamentary soldiers who served in Ireland, and to English people who had settled there before the war.

Scotland, Civil War

The execution of Charles I altered the dynamics of the Civil War in Scotland, which had raged between Royalists and Covenanters since 1644. By 1649, the struggle had left the Royalists there in disarray and their erstwhile leader, the Marquess of Montrose, had gone into exile. However, Montrose, who had raised a mercenary force in Norway, later returned, but did not succeed in raising many Highland clans and the Covenanters defeated his army at the Battle of Carbisdale in Ross-shire on 27 April 1650. The victors captured Montrose shortly afterwards and took him to Edinburgh. On 20 May the Scottish Parliament sentenced him to death and had him hanged the next day.

Charles II landed in Scotland at Garmouth in Moray on 23 June 1650 and signed the 1638 National Covenant and the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant immediately after coming ashore. With his original Scottish Royalist followers and his new Covenanter allies, King Charles II became the greatest threat facing the new English republic. In response to the threat, Cromwell left some of his lieutenants in Ireland to continue the suppression of the Irish Royalists and returned to England.

He arrived in Scotland on 22 July 1650 and proceeded to lay siege to Edinburgh. By the end of August disease and a shortage of supplies had reduced his army, and he had to order a retreat towards his base at Dunbar. A Scottish army, assembled under the command of David Leslie, tried to block the retreat, but Cromwell defeated them at the Battle of Dunbar on September 3. Cromwell's army then took Edinburgh, and by the end of the year his army had occupied much of southern Scotland.

In July 1651, Cromwell's forces crossed the Firth of Forth into Fife and defeated the Scots at the Battle of Inverkeithing (20 July 1651). The New Model Army advanced towards Perth, which allowed Charles, at the head of the Scottish army, to move south into England. Cromwell followed Charles into England, leaving George Monck to finish the campaign in Scotland. Monck took Stirling on 14 August and Dundee on 1 September. The next year, 1652, saw the mopping up of the remnants of Royalist resistance, and under the terms of the "Tender of Union".

Despite the triumph of Calvinist forces in the south and lowlands of Scotland, many Scottish Highlands clans remained either Catholic or Episcopalian in sympathy. The Catholic Clan MacDonald was subject to the Glencoe Massacre for being late in pledging loyalty to the Protestant King William III in 1691. And Highland clans rallied to the support of Catholic claimants to the British throne in the failed Jacobite Risings of the erstwhile Stuart King James III in 1715 and Charles Edward Stuart in 1745.

Denmark

In 1524, King Christian II converted to Lutheranism and encouraged Lutheran preachers to enter Denmark despite the opposition of the Danish diet of 1524. Following the death of King Frederick I in 1533, war broke out between Catholic followers of Count Christoph of Oldenburg, and the firmly Lutheran Count Christian of Holstein. After losing his main support in Lübeck, Christoph quickly fell to defeat, finally losing his last stronghold of Copenhagen in 1536. Lutheranism was immediately established, the Catholic bishops were imprisoned, and monastic and church lands were soon confiscated to pay for the armies that had brought Christian to power. In Denmark this increased royal revenues by 300%.

Thirty Years' War. In 1625 Christian IV of Denmark, who was also the Duke of Holstein, agreed to help the Lutheran rulers of neighbouring Lower Saxony against the forces of the Holy Roman Empire by intervening militarily. Denmark's cause was aided by France which, together with England, had agreed to help subsidize the war. Christian had himself appointed war leader of the Lower Saxon Alliance and raised an army of 20,000–35,000 mercenaries. Christian, however, was forced to retire before the combined forces of Imperial generals Albrecht von Wallenstein and Tilly. Wallenstein's army marched north, occupying Mecklenburg, Pomerania, and ultimately Jutland. However, lacking a fleet, he was unable to take the Danish capital on the island of Zealand. Peace negotiations were concluded in the Treaty of Lübeck in 1629, which stated that Christian IV could keep his control over Denmark if he would abandon his support for the Protestant German states.

See also

References

- ↑ Van der Horst, Han (2000). Nederland, de vaderlandse geschiedenis van de prehistorie tot nu (in Dutch) (3rd ed.). Bert Bakker. p. 133. ISBN 90-351-2722-6.

- ↑ Spaans, J. "Catholicism and Resistance to the Reformation in the Northern Netherlands". In: Benedict, Ph., and others (eds), Reformation, Revolt and Civil War in France and the Netherlands, 1555–1585 (Amsterdam 1999), 149–163).

- ↑ Salmon, pp.136-7.

- ↑ Jouanna, p.181.

- ↑ Jouanna, p.182.

- ↑ Jouanna, pp.184-5.

- ↑ Ellis, S. "The Tudors and the origins of the modern Irish states: A standing army". In: Bartlett,Thomas, A Military History of Ireland (Cambridge 1996), 125-131).

- ↑ MacGregor 1957, p. 127

- Greengrass, Mark. The European Reformation 1500-1618. Longman, 1998. ISBN 0-582-06174-1

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Reformation: A History. New York: Penguin 2003.

| ||||||||||||||