Cathedral Range State Park

| Cathedral Range State Park Victoria | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

The ridge of the Cathedral Range looking south | |

Cathedral Range State Park | |

| Nearest town or city | Buxton |

| Coordinates | 37°22′49″S 145°44′09″E / 37.38028°S 145.73583°ECoordinates: 37°22′49″S 145°44′09″E / 37.38028°S 145.73583°E |

| Area | 3,577 hectares (8,840 acres) |

| Managing authorities | Parks Victoria |

| Website | Cathedral Range State Park |

| See also | Protected areas of Victoria |

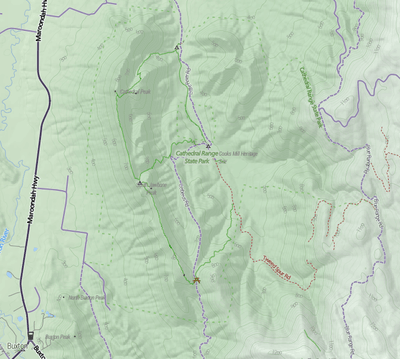

The Cathedral Range State Park is located in Victoria, Australia, approximately 100 kilometres (62 mi) north-east from Melbourne.[1] It is situated between the towns Buxton and Taggerty and runs parallel to Maroondah Highway.[1] The Cathedral Range was declared a State Park on 26 April 1979.[2] It consists of 3,577 hectares[3] and contains the rugged Razorback and spectacular peaks of the Cathedral Range, Little River and forested hills of the Blue Range.[2] Due to its close proximity to Melbourne the Cathedral Ranges are a popular destination for both day and weekend adventures. Bushwalking, camping, rock climbing and abseiling are some of the more popular activities available.[2] Cathedral Range State Park is listed as Category II under the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas[4] and is an example of a park that can be used for recreation, education and conserving natural ecosystems.[2]

History

European settlement of the Acheron area begun in 1839 when they selected land for the Acheron Run.[5] The Taggerty Run was selected for 7 years after the Acheron Run in 1846. This area included the Cathedral Range area.[5] The Taggerty Run consisted of difficult country and was described as being ‘completely in the ranges'.[6] This difficult country of rocky soils and steep slopes discouraged the settlers from building there, so instead the land was grazed until the 1930s when wild dogs became destructive.[5] Soon after grazing in the Cathedral Range area ended, logging and milling occurred in the 1930s to the 1970s in the Little River and Storm Creek catchments.[2] In 1938 the Cathedral Mill, now known as Cooks Mill, was established near the junction of Little River and Storm Creek.[5] The mill ceased operating in 1955,[2] however logging continued until late 1971.[7] Remnants of Cooks Mill remain at the Cathedral Range State Park and is protected as a historic site.[2]

Aboriginal heritage

The traditional land owners of the Murrindindi Shire, including the Cathedral Range, is the Aboriginal people who are members of the Wurundjeri tribe and the Taungurong language speakers.[8] An important area for members of the Taungurong people is located in the Acheron River valley, located to the west of the Cathedral Range State Park.[2] Aboriginal Affairs Victoria have recorded two sites, one containing a scarred tree and the other an isolated artefact, in the Cathedral Range State Park.[2]

Geology and land features

The Cathedral Ranges consist of sandstone and shale that were laid down over 400 million years ago[9] during the Upper Silurian period.[10] These have since eroded into the spectacular peaks of the Cathedral Ranges.[9] The range is approximately 7 km long and 1.5 km wide.[1] The highest peak is Sugarloaf Peak which stands at 923m, located at the southern end of the range.[2] At the opposite end of the range stands the second highest peak at 814m, known as the Cathedral North Peak.[2] These peaks are separated by a narrow saddle, referred to as the Jawbone saddle.[5] The eastern side of the State Park borders onto the Cerberean Caldera, formed by a volcanic eruption approximately 374 million years ago.[11] Consequently, the geology of the area consists of sedimentary and volcanic formations originating in the Upper Devonian Period.[11] The soils are mostly red clays that are resistant to erosion.[1]

Rivers

There are two permanent rivers found in the Cathedral Range State Park; Little River and Storm Creek.[2] Little River flows north-west and merges with the Acheron River in Taggerty.[12] The township of Taggerty receives their water directly from Little River.[1] The river runs through the camping and picnic sites in the park, providing the potential of pollution to the river.[1] Storm Creek intercepts with Little River near Cooks Mill, located in the Cathedral Range State Park.[2] The water levels of the rivers can get high after heavy rainfall, with flooding being a common occurrence.[1] The last significant flooding occurring in 1996 when extensive damage occurred on Little River Road.[1]

Biodiversity

The Cathedral Range State Park is home to a large number of species. The existence of some communities been have recognized as being significant in the State Park, as well as the occurrence of some rare species.[2]

Flora

The park contains a broad range of vegetation communities, with the Ecological Vegetation Classes (EVCs) of the area including herb-rich foothill forest, grassy dry forest, damp forest and riparian forest.[13] The vegetation ranges from Manna Gum Tall Open Forest found along the banks of Little River to Myrtle Beech Closed Forest found above 900 m.[2] The dry rocky slopes are covered with open forest, with the main species being red stringybark (Eucalyptus macrorhyncha), broad-leaved peppermint (Eucalyptus dives) and long-leaved box (Eucalyptus goniocalyx).[5] The moist river valleys contain candlebark gum (Eucalyptus rubida) and narrow-leaved peppermint (Eucalyptus radiata).[5] The summit of Sugarloaf Peak contains a community of snow gum (Eucalyptus pauciflora) and just below this is a community of alpine ash (Eucalyptus delegatensis) extending down to the Sugarloaf Saddle.[5]

A community noted to be significant found in the State Park is the existence of myrtle beech (Nothofagus cunninghamii) with the woolly tea-tree (Leptospermum lanigerum).[2] This community is marked as significant as it is known to occur in only one other location—Baw Baw National Park.[2]

The park is home to a variety of native orchids, appearing in spring and summer each year. These orchids are the alpine greenhood (Pterostylis alpina), pink fingers (Caladenia carnea), wax lips (Glossodia major) and the bird orchid.[14]

The Cathedral Range State Park is also home to some rare species: The bristle-fern (Cephalomanes caudatum) which is considered rare in Victoria,[15] slender tick-trefoil (Desmodium varians) which is poorly known in Victoria[16] and a range of common tussock-grasses considered rare in Victoria.[2]

Fauna

The varying vegetation, climates, rivers and landforms in the park have created an area rich in habitats for native animals. A study was conducted in 1996 on the fauna found at the Cathedral Range State Park. The finding of this study was that the park is home to seventeen native mammals, eight reptiles, one amphibian, one fish and eighty-seven native birds.[17] Common animals observed in the park include the common wombat (Vombatus ursinus), eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), the superb lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae), peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) and satin bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus violaceus).[2] Mountain galaxias (Galaxias olidus), a native freshwater fish,[18] was observed in the Little River just before the Little River falls.[17] It is thought that these falls act as a barrier to trout, one of the major predators of the Mountain Galaxias.[2] There have also been occasional sightings of the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) in the Little River.[2]

Rare species

The 1996 fauna survey revealed some rare species found at the park that are important for conservation purposes.[17]

Leadbeater's possum The Leadbeater's possum (Gymnobelideus leadbeateri) is an iconic Australian species that is listed as critically endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.[19] It is found in the wet ash forests of Victoria and has become endangered due to logging, recurrent bushfires and the decline of large trees containing hollows.[20] Although there have been no sightings of the Leadbeater's Possum at the Cathedral Range it is suspected to occur there. Sightings have been made at Tweed Spur, only 3 km south from the Range.[17] The community of Alpine Ash found in the park is suitable habitat for the possum.[2]

Brush-tailed Phascogale The brush-tailed phascogale (Phascogale tapoatafa) is a small carnivores nocturnal marsupial.[21] It is classified as near threatened under the IUCN guidelines and as rare in Victoria.[21] The reasons for its decline in Victoria are unknown, however the destruction of its preferred habitat is thought to have contributed to its decline.[21] There are no official records of this species in the Cathedral Range, however suitable habitat exists in the park and its occurrence in the park is suspected.[2]

Powerful Owl The powerful owl (Ninox strenua) is Australia's largest owl and is listed as threatened in Victoria under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988.[22] They have been observed roosting along the Little River and it is suspected that one, if not more, pairs of Powerful Owls are residents in the park.[2]

Sambar Deer The sambar deer (Rusa unicolor) are a large deer native to South-East Asia.[23] They were introduced to Victoria in the 1860s for recreational hunting.[23] There is concern on the ecological impacts this introduced species are creating, however in Victoria they are listed as wildlife under the Wildlife Act 1975.[23] They are found in low numbers in the Cathedral Range State Park, however their population need to be monitored to minimize the risk they pose to the biodiversity of the park.[2]

Environmental threats

The Cathedral Range State Park's biodiversity is threatened by introduced flora and fauna and pathogens.

Flora

The park is home to a number of introduced plants that have become a pest. There are four main plants that are recognised as major threats to the Cathedral Range environment. These pests plants are blackberry, tutsan (Hypericum androsaemum), Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica) and Monterey pine (Pinus radiata).[2] Blackberry is a highly invasive plant that is listed as a weed of national significance.[24] The Japanese honeysuckle has been recorded in the riparian zones of the park.[2] Monterey pine has been invading the park from pine plantations located on the outskirts and in the inner block of the park.[2]

Fauna

Introduced fauna that prey on the local wildlife include foxes and feral cats and dogs.[2] Surveys have found that a large number of Australian animals are killed each year as a result of introduced predators.[25] Feral goats have been observed near the state park.[2] Feral goats are destructive to the environment by overgrazing the vegetation and by disturbing the soil with their hooves.[26]

Pathogens

Investigations into the pathogens found at the park have not yet been conducted. The cinnamon fungus (Phytophthora cinnamomi), a pathogenic soil fungus resulting in devastating effects on plant communities,[27] has not yet been recorded as occurring in the park.[2] Myrtle wilt is suspected as occurring in the park.[2] It is caused by a fungus, Chalara australia, that infects myrtle beech trees and results in their gradual death.[28] The pathogen has been suggested for listing as a potentially threatening process under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act.[2]

Management

Cathedral Range State Park is managed by Parks Victoria. Management of the park concentrates on the conserving the natural, cultural and scenic features while still providing for a range of recreational activities for visitors. Parks Victoria list six main management directions for the park.[2]

- To provide significant flora and fauna with special protection[2]

- Management strategies for pest plant and animals will be implemented with the aim of eradicating or controlling these species[2]

- Cooks Mill will have ongoing protection and interpretation[2]

- Campsite facilities will be rationalized and enhanced[2]

- Climbing sites will be monitored for erosion and other impacts[2]

- Promotion of the park as a conservation reserve with outstanding scenery, natural history and recreational opportunities[2]

The ongoing management of Cathedral Range State Park is vital. It preserves the cultural heritage and natural ecosystems of the area and provides protection for some rare communities and species while allowing the public to enjoy the spectacular landscape.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Parks Victoria (1998). Cathedral Range State Park: draft management plan. Parks Victoria, Kew, Victoria

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 Parks Victoria (1998). Cathedral Range State Park: management plan. Parks Victoria

- ↑ Parks Victoria (2013). Cathedral Range State Park visitor guide. Parks Victoria.

- ↑ "Collaborative Australian Protected Area Database CAPAD08". Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Populations and Communities, Commonwealth of Australia. 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Taylor, R. (1999). Wild places of greater Melbourne. CSIRO Publishing, Canberra

- ↑ Macdonald, J. (2009). James Watson and ‘Flemington': a gentleman's estate. Journal of the C J La Trobe Society 8: 21–25

- ↑ Evans, P. (1995). Rails to Rubicon. Light Rail Preservation Society of Australia

- ↑ Murrindindi Shire Council. (2011). Murrindindi Shire Council annual report 2010-2011. murrindindi.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 20-05-15

- 1 2 Parks Victoria (1999). Victoria's National Parks: explorer guide. See Australia Guides, Healesville

- ↑ Hills, E. S. (1932). The geology of Marysville, Victoria. Geological Magazine 69: 145–166

- 1 2 Clemens, J.D. and Birch, W.D. (2012). Assembly of a zoned volcanic magma chamber from multiple magma batches: The Cerberean Caldrun, Marysville Igneous Complex, Australia. Lithos 155: 272–288

- ↑ Downs, B.J., Bellgrove, A. and Street, J.L. (2005). Drifting or Walking? Colonisation routes used by different instars and species of lotic, macroinvertebrate filter feeders. Marine and Freshwater Research 56: 815–824

- ↑ Nelson, J. and Jemison, M. (2012). Surveys and management guidelines for dunnarts in Cathedral Range State Park and Big River Catchment. Victorian Government, Department of Sustainability and Environment.

- ↑ Parks Victoria. (2015). Cathedral Range State Park: Environment. http://parkweb.vic.gov.au/explore/parks/cathedral-range-state-park/environment. Retrieved 20 May 2015

- ↑ DEPI. (2014). Advisory list of rare or threatened plants in Victoria 2014. www.depi.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 20-05-15

- ↑ The Atlas of Living Australia. Desmodium varians (Labill.) G.Don: Slender Tick Trefoil. http://bie.ala.org.au/species/urn:lsid:biodiversity.org.au:apni.taxon:636364. Retrieved 20-05-15

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, S.J., White, M.D. and Weeks, M. (1996). Cathedral Range State Park fauna survey report. Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Victoria.

- ↑ Lintermans, M. (2000). Recolonization by the mountain galaxias Galaxias olidus of a montanestream after the eradication of rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Marine and Freshwater Research 51: 799–804

- ↑ Department of the Environment. (2015). Gymnobelideus leadbeateri in Species Profile and Threats Database, Department of the Environment, Canberra. http://www.environment.gov.au/sprat. Retrieved 20-05-15

- ↑ Lindenmayer, B., Blair, D., McBurney, L. and Banks, S. (2014). Preventing the Extinction of an Iconic Globally Endangered Species–Leadbeater's Possum (Gymnobelideus leadbeateri). Journal of Biodiversity Endangered Species 2: 1–7

- 1 2 3 Department of Sustainability and Environment. (1997). Action statement: Brush-tailed Phascogale Phascogale tapoatafa. www.depi.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 20-05-15

- ↑ Newton, I., Kavanagh, R., Olsen, J. and Taylor, I. (2002). Ecology and Conservation of Owls. CSIRO Publishing

- 1 2 3 Bilney, R.J. (2013). Antler rubbing of yellow-wood by Sambar in East Gippsland, Victoria. The Victorian Naturalist 130: 68–74

- ↑ Amor, R.L. (1974). Ecology and control of blackberry (Rubus fruticosus L. agg.). Weed Research 14: 231–238

- ↑ Dickman, C.R. (1996). Overview of the impacts of feral cats on Australian native fauna. Australian Nature Conservation Agency

- ↑ Parkes, J., Henzell R. and Pickles, G. (1996). Managing vertebrate pests: feral goats. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra

- ↑ Newell, G.R. (1998). Characterization of vegetation in an Australian open forest community affected by cinnamon fungus (Phytophthora cinnamomi): implications for faunal habitat quality. Plant Ecology 137: 55–70

- ↑ Kile, G. A., Packham, J. M., Elliot, H. J. and Griffith, J. A. (1989). Myrtle wilt and its possible management in association with human disturbance of rainforest in Tasmania. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 19: 256–264

| ||||||||||||