Catalonia

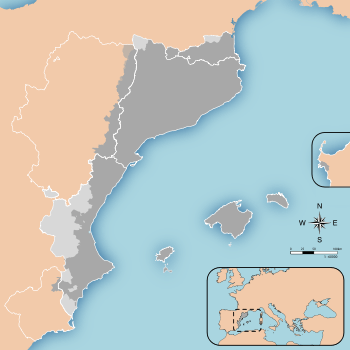

Catalonia (Catalan: Catalunya, Occitan: Catalonha, Spanish: Cataluña)[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] is an autonomous community of Spain politically designated as a nationality.[lower-alpha 3][5] Catalonia consists of four provinces: Barcelona, Girona, Lleida, and Tarragona. The capital and largest city is Barcelona, the second-largest city in Spain and the centre of one of the largest metropolitan areas in Europe and the Mediterranean basin.

Catalonia comprises most of the territory of the former Principality of Catalonia, with the remainder now part of France's Pyrénées-Orientales. It is bordered by France and Andorra to the north, the Mediterranean Sea to the east, and the Spanish autonomous communities of Aragon to the west and Valencia to the south. The official languages are Catalan, Spanish, and the Aranese dialect of Occitan.[6]

In the late 8th century, the counties of the March of Gothia and the Hispanic March were established by Francia as feudatory vassals across and near the eastern Pyrenees as a defensive barrier against Muslim invasions. The eastern counties of these marches were united under the rule of the Frankish vassal the Count of Barcelona, and were later called Catalonia. In 1137, The Principality of Catalonia and the Kingdom of Aragon were united by marriage under the Crown of Aragon, and the Principality of Catalonia became the base for the Crown of Aragon's naval power and expansionism in the Mediterranean. In the later Middle Ages Catalan literature flourished. Between 1469 and 1516, the King of Aragon and the Queen of Castile married and ruled their kingdoms together, retaining all their distinct institutions, Courts (parliament), and constitutions. During the Franco-Spanish War (1635–59), Catalonia revolted (1640-52) against a large and burdensome presence of the Spanish army in its territory, becoming a republic under French protection. Within a brief period France took full control of Catalonia until it was largely reconquered by the Spanish army. Under the terms of the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659, which ended the wider Franco-Spanish War, the Spanish Crown ceded the northern parts of Catalonia, mostly incorporated in the county of Roussillon, to France. During the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14), the Crown of Aragon sided against the Bourbon Philip V of Spain, whose subsequent victory led to the abolition of non-Castilian institutions in all of Spain and the replacement of Latin and other languages (such as Catalan) with Spanish in legal documents.

In the nineteenth century Catalonia was severely affected by the Napoleonic and Carlist Wars. In the second half of the century Catalonia experienced industrialisation. As wealth from the industrial expansion grew, Catalonia saw a cultural renaissance coupled with incipient nationalism while several workers movements appeared. In 1914, the four Catalan provinces formed a Commonwealth, and with the return of democracy during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–39), the Generalitat of Catalonia was restored as an autonomous government. After the Spanish Civil War, the Francoist dictatorship enacted repressive measures, abolishing Catalan institutions and banning the official use of the Catalan language again. From the late 1950s through to the early 1970s, Catalonia saw rapid economic growth, drawing many workers from across Spain, making Barcelona one of Europe's largest industrial metropolitan areas and Catalonia into a major tourist destination. Since the Spanish transition to democracy (1975–82), Catalonia has gained some political and cultural autonomy and is now one of the most economically dynamic communities of Spain.

On 9 November 2015, the Catalan parliament adopted a statute aiming for full independence from Spain by 2017. It was eventually suspended by the Spanish Constitutional Court.

Etymology and pronunciation

The name Catalunya (Catalonia)—spelled Cathalonia, or Cathalaunia, in Mediaeval Latin—began to be used for the homeland of the Catalans (Cathalanenses) in the late 11th century and was probably used before as a territorial reference to the group of counties that comprised part of the March of Gothia and March of Hispania under the control of the Count of Barcelona and his relatives.[7] The origin of the name Catalunya is subject to diverse interpretations because of a lack of evidence.

One theory suggests that Catalunya derives from the name Gothia (or Gauthia) Launia ("Land of the Goths"), since the origins of the Catalan counts, lords and people were found in the March of Gothia, known as Gothia, whence Gothland > Gothlandia > Gothalania > Cathalaunia > Catalonia theoretically derived.[8][9] During the Middle Ages, Byzantine chroniclers claimed that Catalania derives from the local medley of Goths with Alans, initially constituting a Goth-Alania.[10]

Other less plausible theories suggest:

- Catalunya derives from the term "land of castles", having evolved from the term castlà or castlan, the medieval term for the ruler of a castle.[8][11] This theory therefore suggests that the names Catalunya and Castile have a common root.

- The source is of Celtic origin, meaning "chiefs of battle". Although the area is not known to have been occupied by Celts, a Celtic culture was present within the interior of Iberia in pre-Roman times.[12]

- The Lacetani, an Iberian tribe that lived in the area and whose name, due to the Roman influence, could have evolved by metathesis to Katelans and then Catalans.[13][14]

In English, Catalonia is pronounced /kætəˈloʊniə/. The native name, Catalunya, is pronounced [kətəˈluɲə] in Central Catalan, the most widely spoken variety whose pronunciation is considered standard.[15] The Spanish name is Cataluña ([kataˈluɲa]), and the Aranese name is Catalonha ([kataˈluɲɔ]).

History

Pre-Roman and Roman period

In pre-Roman times, the area that is now called Catalonia in the north-east of Iberian Peninsula, like the rest of the Mediterranean side of the peninsula, was populated by the Iberians. Coastal trading colonies were established by the ancient Greeks, who settled around the Roses area. Both Greeks and Carthaginians briefly ruled the territory in the course of the Second Punic War and traded with the surrounding Iberian population.

After the Carthaginian defeat by the Roman Republic, the north-east of Iberia became the first to come under Roman rule and became part of Hispania, the westernmost part of the Roman Empire. Tarraco (modern Tarragona) was one of the most important Roman cities in Hispania and the capital of the province of Tarraconensis.

Middle Ages

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the area was conquered by the Visigoths and was ruled as part of the Visigothic Kingdom for almost two and a half centuries. In 718, it came under Muslim control and became part of Al-Andalus, a province of the Umayyad Caliphate. From the conquest of Roussillon in 760, to the conquest of Barcelona in 801, the Frankish empire took control of the area between Septimania and the Llobregat river from the Muslims and created heavily militarised, self-governing counties. These counties formed part of the Gothic and Hispanic marches, a buffer zone in the south of the Frankish empire in the former province of Septimania and in the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula, to act as a defensive barrier for the Frankish empire against further Muslim invasions from Al-Andalus.

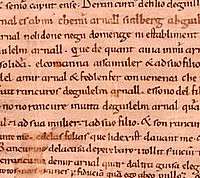

These counties came under the rule of the counts of Barcelona, who were Frankish vassals nominated by the emperor of the Franks, to whom they were feudatories (801–987). The earliest known use of the name "Catalonia" for these counties dates to 1117.

In 987 Borrell II, Count of Barcelona, did not recognise Hugh Capet as his king, making his successors (from Ramon Borell I to Ramon Berenguer IV) de facto independent of the Carolingian crown. At the start of eleventh century the Catalan Counties suffer an important process of feudalisation, partially controlled by the Peace and Truce Assemblies and by the power and negotiations of the Counts of Barcelona like Ramon Berenguer I. In 1137, Ramon Berenguer IV, Count of Barcelona decided to accept King Ramiro II of Aragon's proposal to marry Queen Petronila, establishing the dynastic union of the County of Barcelona with the Kingdom of Aragon, joining the Crown of Aragon and making the Catalan counties that were united under the county of Barcelona into a principality of the Aragonese Crown.

In 1258, by means of the Treaty of Corbeil, the Count of Barcelona and King of Aragon, of Mallorca and of Valencia, James I of Aragon renounced his family rights and dominions in Occitania and recognised the king of France as heir of the Carolingian Dynasty. The king of France formally relinquished his nominal feudal lordship over all the Catalan counties, excepting the County of Foix despite the opposition of the King of Aragon and Count of Barcelona. This treaty transformed the principality's de facto union with Aragon into a de jure one and was the origin of the definitive separation between both geographical areas Catalonia and Languedoc.

As a coastal territory, Catalonia became the base of the Aragonese Crown's maritime forces, which spread the power of the Aragonese Crown in the Mediterranean, and made Barcelona into a powerful and wealthy city. In the period 1164–1410 new territories, the Kingdom of Valencia, the Kingdom of Majorca, Sardinia, the Kingdom of Sicily, Corsica and (briefly) the Duchy of Athens, were incorporated into the dynastic domains of the House of Aragon.

At the same time, the Principality of Catalonia developed a complex institutional and political system based in the concept of pact between the Estates of the realm and the king. The laws had to be approved in the General Court of Catalonia, one of the first parliamentary bodies of Europe that banned the royal power to create legislation unilaterally (since 1283).[16] The Courts were composed by the three Estates, were presided by the king of Aragon, and approved the constitutions, which created a compilation of rights for the whole citizens of the Principality. In order to recapt general taxes, the Courts of 1359 established a permanent representation of deputies, called Deputation of the General and later sometimes known as Generalitat, that gained an important political power in the next centuries.

The domains of the Aragonese Crown were severely affected by the Black Death pandemic and by later outbreaks of the plague. Between 1347 and 1497 Catalonia lost 37 percent of its population.[17]

In 1410, King Martin I died without surviving descendants. Under the Compromise of Caspe, Ferdinand from the Castilian House of Trastámara received the Crown of Aragon as Ferdinand I of Aragon.

Modern Era

The grandson of Martin I, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile were married in 1469, later taking the title the Catholic Monarchs; subsequently, this event was seen by historiographers as the dawn of a unified Spain. At that point, though united by marriage, the Crowns of Castile and Aragon maintained distinct territories, each kept its own traditional institutions, parliaments and laws. Castile commissioned expeditions to the Americas and benefited from the riches acquired in the Spanish colonisation of the Americas, but in time, also carried the main burden of military expenses of the united Spanish kingdoms. After Isabella's death, Ferdinand II personally ruled both kingdoms.

By virtue of descent from his maternal grandparents, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, in 1516 Charles I of Spain became the first king to rule Castile and Aragon simultaneously by his own right. Following the death of his paternal (House of Habsburg) grandfather, Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, he was also elected Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, in 1519.[18]

The Catalan Revolt (1640–52) saw Catalonia rebel (briefly in 1641 as a republic) with French help against the Spanish Crown for overstepping Catalonia's traditional rights during the Thirty Years' War. Most of Catalonia was reconquered by the Spanish monarchy but Catalan rights were recognised. Roussillon was lost to France.

The most significant conflict concerning the governing monarchy was the War of the Spanish Succession, which began when the childless Charles II of Spain, the last Spanish Habsburg, died without an heir in 1700. Charles II had chosen Philip V of Spain from the French House of Bourbon. Catalonia, like other territories that formed the Crown of Aragon, rose up in support of the Austrian Habsburg pretender Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor in his claim for the Spanish throne as Charles III of Spain. The fight between the houses of Bourbon and Habsburg for the Spanish Crown split Spain and Europe.

The fall of Barcelona on 11 September 1714 to the Bourbon king Philip V militarily ended the Habsburg claim to the Spanish Crown, which became legal fact in the Treaty of Utrecht. Philip felt that he had been betrayed by the Catalan Courts, as it had initially sworn its loyal to him when he had presided over it in 1701. In retaliation for the betrayal, the first Bourbon king introduced the Nueva Planta decrees that incorporated the territories of the Crown of Aragon, including Catalonia, as provinces under the Crown of Castile in 1716, terminating their separate institutions, laws and rights, within a united kingdom of Spain.

Industrialisation and beyond

At the beginning of the nineteenth century Catalonia was severely affected by the Napoleonic Wars, in which it was annexed to France between 1812 and 1814, and Carlist Wars. In the latter half of the 19th century, Catalonia became an important industrial center, building the first railway line of the Iberian Peninsula, between Barcelona and Mataró in 1848. Barcelona became a revolutionary focus, demanding many times the end of the conservative regime and even the creation of a federal republic. To this day it remains one of the most industrialised parts of Spain.

In the first third of the 20th century, Catalonia gained and lost varying degrees of autonomy several times. In 1914, the four Catalan provinces were authorized to create a Commonwealth (Mancomunitat), without any legislative power or specific autonomy, that was disbanded in 1925 by the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. After the fall of the dictator and a brief proclamation of the Catalan Republic, it received its first Statute of Autonomy during the Second Spanish Republic (1931), establishing an autonomous body, the Generalitat of Catalonia, that included a parliament, a government and a court of appeal, and Francesc Macià was elected its first President. This period was marked by political unrest and the preeminence of Revolutionary Catalonia during the Spanish Civil War (1936–39). The Anarchists had been active throughout the early 20th century, achieving the first eight-hour workday in Europe in 1919.

The defeat of the Second Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War brought fascist Francisco Franco to power as dictator. His regime imposed linguistic, political and cultural restrictions across Spain. In Catalonia, any kind of public activities associated with Catalan nationalism, republicanism, anarchism, socialism, liberalism, democracy or communism, including the publication of books on those subjects or simply discussion of them in open meetings, was banned. Franco's regime banned the use of Catalan in government-run institutions and during public events. The Catalan self-government, and also its institutions, were suppressed. The pro-Republic of Spain President of Catalonia, Lluís Companys, was taken to Spain from his exile in the German-occupied France, tortured and executed in the Montjuïc Castle of Barcelona for the crime of 'military rebellion'.[19]

During later stages of Francoist Spain, certain folkloric and religious celebrations in Catalan resumed and were tolerated. Use of Catalan in the mass media had been forbidden, but was permitted from the early 1950s[20] in the theatre. Publishing in Catalan continued throughout the dictatorship.[21]

The years after the war were extremely hard. Catalonia, like many other parts of Spain, had been devastated by the war. Recovery from the war damage was slow and made more difficult by the international trade embargo against Franco's dictatorial regime. By the late 1950s the country had recovered its pre-war economic levels and in the 1960s was the second fastest growing economy in the world in what became known as the Spanish miracle. During this period there was a spectacular growth of industry and tourism in Catalonia that drew large numbers of workers to the region from across Spain and made the area around Barcelona into one of Europe's largest industrial metropolitan areas.

After Franco's death in 1975, Catalonia voted for the adoption of a democratic Spanish Constitution in 1978, in which Catalonia recovered political and cultural autonomy, restoring the Generalitat from the exile in 1977, and approved a new Statute of Autonomy in 1979. Today, Catalonia is one of the most economically dynamic communities of Spain. The Catalan capital and largest city, Barcelona, is a major international cultural centre and a major tourist destination. In 1992, Barcelona hosted the Summer Olympic Games.

21st Century

On 9 November 2015, Catalan lawmakers approved a plan for secession from Spain by 2017 with a vote 72 to 63. The plan was suspended by the Constitutional Court.[22][23]

Geography

Climate

The climate of Catalonia is diverse. The populated areas lying by the coast in Tarragona, Barcelona and Girona provinces feature a Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa). The inland part (including the Lleida province and the inner part of Barcelona province) show a mostly continental Mediterranean climate (Köppen Csa). The Pyrenean peaks have a mountain (Köppen H) or even Alpine climate (Köppen ET) at the highest summits, while the valleys have a maritime or oceanic climate sub-type (Köppen Cfb).

In the Mediterranean area, summers are dry and hot with sea breezes, and the maximum temperature is around 26–31 °C (79–88 °F). Winter is cool or slightly cold depending on the location. It snows frequently in the Pyrenees, and it occasionally snows at lower altitudes, even by the coastline. Spring and autumn are typically the rainiest seasons, except for the Pyrenean valleys, where summer is typically stormy.

The inland part of Catalonia is hotter and drier in summer. Temperature may reach 35 °C (95 °F), some days even 40 °C (104 °F). Nights are cooler there than at the coast, with the temperature of around 14–17 °C (57–63 °F). Fog is not uncommon in valleys and plains; it can be especially persistent, with freezing drizzle episodes and subzero temperatures during winter (record from −36 °C), along the Segre and in other river valleys.

- Pyrenees

- Pre-Pyrenees

- Catalan Central Depression

- Smaller mountain ranges of the Central Depression

- Catalan Transversal Range

- Catalan Pre-Coastal Range

- Catalan Coastal Range

- Catalan Coastal Depression and other coastal and pre-coastal plains

Topography

Catalonia has a marked geographical diversity, if we consider the relatively small size of its territory. The geography is conditioned by the Mediterranean coast, with 580 kilometres of coastline, and large relief units of the Pyrenees to the north. The Catalan territory is divided into three main geomorphological units:[24]

- The Pyrenees: mountainous formation that connects the Iberian Peninsula with the European continental territory, and located in the north of Catalonia;

- The Catalan Coastal mountain ranges or the Catalan Mediterranean System: an alternating delevacions and planes parallel to the Mediterranean coast;

- The Catalan Central Depression: structural unit which forms the eastern sector of the Valley of the Ebre.

Hydrography

Most of Catalonia belongs to the Mediterranean Basin. The Catalan hydrographic network consists of two important basins, the one of the Ebro and the one that comprises the internal basins of Catalonia (respectively covering 46.84% and 51.43% of the territory), all of them flow to the Mediterranean. Furthermore, there is the Garona river basin that flows to the Atlantic Ocean, but it only covers 1.73% of the Catalan territory.

The hydrographic network can be divided in two sectors, an occidental slope or Ebre river slope and one oriental slope constituted by minor rivers that flow to the Mediterranean along the Catalan coast. The first slope provides an average of 18,700 cubic hectometres (4.5 cu mi) per year, while the second only provides an average of 2,020 hm3 (0.48 cu mi)/year. The difference is due to the big contribution of the Ebre river, from which the Segre is an important tributary. Moreover, in Catalonia there is a relative wealth of groundwaters, although there is inequality between comarques, given the complex geological structure of the territory.[25] In the Pyrenees there are many small lakes, remnants of the ice age. The biggest is the one of Banyoles.

The Catalan coast is almost rectilinear, with a length of 580 kilometres (360 mi) and few landforms—the most relevant are the Cap de Creus and the Gulf of Roses to the north and the Ebro Delta to the south. The Catalan Coastal Range hugs the coastline, and it is split into two segments, one between L'Estartit and the town of Blanes (the Costa Brava), and the other at the south, at the Costes del Garraf.[26]

The principal rivers in Catalonia are the Ter, Llobregat, and the Ebre, all of which run into the Mediterranean.

Politics

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Catalonia |

|

Statute |

|

Judiciary

|

|

Public order |

|

Divisions

|

|

Politics portal |

After Franco's death in 1975 and the adoption of a democratic constitution in Spain in 1978, Catalonia recovered and extended the powers that it had gained in the Statute of Autonomy of 1932[27] but lost with the fall of the Second Spanish Republic[28] at the end of the Spanish Civil War in 1939.

This autonomous community has gradually achieved more autonomy since the approval of the Spanish Constitution of 1978. The Generalitat holds exclusive jurisdiction in culture, environment, communications, transportation, commerce, public safety and local government, and shares jurisdiction with the Spanish government in education, health and justice.[29] In all, the current system grants Catalonia with "more self-government than almost any other corner in Europe".[30]

A relatively large sector of the population supports the ideas and policies of Catalan nationalism,[31] a political movement which defends the notion that Catalonia is a separate nation and advocates for either further political autonomy or full independence of Catalonia.

The support for Catalan nationalism ranges from a demand for further autonomy and the federalisation of Spain to the desire for independence from the rest of Spain, expressed by Catalan independentists.[31] The first survey following the Constitutional Court ruling that cut back elements of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy, published by La Vanguardia on 18 July 2010, found that 46% of the voters would support independence in a referendum.[32] In February of the same year, a poll by the Open University of Catalonia gave more or less the same results.[33] Other polls have shown lower support for independence, ranging from 40 to 49%.[34][35][36]

Since 2011 when the question started to be regularly surveyed by the governmental Center for Public Opinion Studies (CEO), support for Catalan independence has been on the rise.[37] According to the CEO opinion poll from July 2015, 47,4% of Catalans would vote against independence and 45,3% for it.[38]

In hundreds of non-binding local referendums on independence, organised across Catalonia from 13 September 2009, a large majority voted for independence, although critics argued that the polls were mostly held in pro-independence areas. In December 2009, 94% of those voting backed independence from Spain, on a turn-out of 25%.[39] The final local referendum was held in Barcelona, in April 2011. On 11 September 2012, a pro-independence march pulled in a crowd of between 600,000 (according to the Spanish Government), 1.5 million (according to the Guàrdia Urbana de Barcelona), and 2 million (according to its promoters);[40][41] whereas poll results revealed that half the population of Catalonia supported secession from Spain.

Two major factors were Spain's Constitutional Court's 2010 decision to declare part of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia unconstitutional, as well as the fact that Catalonia contributes 19.49% of the central government’s tax revenue, but only receives 14.03% of central government's spending.[42]

Parties that consider themselves either Catalan nationalist or independentist have been present in all Catalan governments since 1980. The largest Catalan nationalist party, Convergence and Union, ruled Catalonia from 1980 to 2003, and returned to power in the 2010 election. Between 2003 and 2010, a leftist coalition, composed by the Catalan Socialists' Party, the pro-independence Republican Left of Catalonia and the leftist-environmentalist Initiative for Catalonia-Greens, implemented policies that widened Catalan autonomy.[43]

In the November 25, 2012 Catalan parliamentary election, sovereigntist parties supporting a secession referendum gathered 59.01% of the votes and hold 87 of the 135 seats in the Catalan Parliament. Parties supporting independence from the rest of Spain obtained 49.12% of the votes and a majority of 74 seats.

Artur Mas, the president of Catalonia, organised early elections and they took place in September 27, 2015. In these elections, Convergència and Esquerra Republicana decided to join, and they presented themselves under the coalition named "Junts pel sí" (in Catalan, "Together for Yes"). Junts pel sí won 62 seats and was the most voted party, and CUP (Candidatura d'Unitat Popular, far-left and independentist party) won another 10, so the sum of all the independentist forces was 72 seats, reaching an absolute majority of seats for the independentist forces, but not in number of individual votes that was 47,74% of the total.[44]

Statute of Autonomy

The Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia is the fundamental organic law, second only to the Spanish Constitution from which the Statute originates.

In the Spanish Constitution of 1978 Catalonia, along with the Basque Country and Galicia, was defined as a "nationality". The same constitution gave Catalonia the automatic right to autonomy, which resulted in the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia of 1979.

Both the 1979 Statute of Autonomy and the current one, approved in 2006, state that "Catalonia, as a nationality, exercises its self-government constituted as an Autonomous Community in accordance with the Constitution and with the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia, which is its basic institutional law, always under the law in Spain".[45]

The Preamble of the 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia states that the Parliament of Catalonia has defined Catalonia as a nation, but that "the Spanish Constitution recognizes Catalonia's national reality as a nationality".[46] While the Statute was approved by and sanctioned by both the Catalan and Spanish parliaments, and later by referendum in Catalonia, it has been subject to a legal challenge by the surrounding autonomous regions of Aragon, Balearic Islands and the Valencian Community,[47] as well as by the conservative People's Party. The objections are based on various issues such as disputed cultural heritage but, especially, on the Statute's alleged breaches of the principle of "solidarity between regions" in fiscal and educational matters enshrined by the Constitution.[48]

Spain's Constitutional Court assessed the disputed articles and on 28 June 2010, issued its judgment on the principal allegation of unconstitutionality presented by the People's Party in 2006. The judgment granted clear passage to 182 articles of the 223 that make up the fundamental text. The court approved 73 of the 114 articles that the People's Party had contested, while declaring 14 articles unconstitutional in whole or in part and imposing a restrictive interpretation on 27 others.[49] The court accepted the specific provision that described Catalonia as a "nation", however ruled that it was a historical and cultural term with no legal weight, and that Spain remained the only nation recognised by the constitution.[50][51][52][53]

Government and law

The Catalan Statute of Autonomy establishes that Catalonia is organised politically through the Generalitat of Catalonia, conformed by the Parliament of Catalonia, the Presidency of the Generalitat, the Government or Executive Council and the other institutions created by the Parliament.

The seat of the Executive Council is the city of Barcelona. Since the restoration of the Generalitat on the return of democracy in Spain, the presidents of Catalonia have been Jordi Pujol i Soley (1980–2003), Pasqual Maragall i Mira (2003–2006), José Montilla (2006–2010) and Artur Mas i Gavarró incumbent as of 2010.

Security forces

Catalonia has its own police force, the Mossos d'Esquadra (officially called Mossos d'Esquadra-Policia de la Generalitat de Catalunya), whose origins date back to the 18th century. Since 1980 they have been under the command of the Generalitat, and since 1994 they have expanded in number in order to replace the national Civil Guard and National Police Corps, which report directly to the Homeland Department of Spain. The national bodies retain personnel within Catalonia to exercise functions of national scope such as overseeing ports, airports, coasts, international borders, custom offices, the identification of documents and arms control, immigration control, terrorism prevention, arms trafficking prevention, amongst others.

Most of the justice system is administered by national judicial institutions. The criminal justice system is uniform throughout Spain, while civil law is administered separately within Catalonia.[54]

Navarre, the Basque Country and Catalonia are the Spanish communities with the highest degree of autonomy in terms of law enforcement.

Political divisions

Catalonia is organised territorially into provinces, further subdivided into comarques and municipalities. The 2006 Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia establishes the administrative organisation of three local authorities: vegueries, comarques, and municipalities.

Provinces

Catalonia is divided administratively into four provinces, the governing body of which is the Deputation (Catalan: Diputació, Spanish: Diputación). The four provinces and their populations are:[55]

- Province of Barcelona: 5,507,813 population.

- Province of Girona: 752,026 population.

- Province of Lleida: 439,253 population.

- Province of Tarragona: 805,789 population.

Municipalities

There are at present 948 municipalities in Catalonia.

| Ranking | Municipality | Comarca | Population[56] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Barcelonès | 1,621,537 | |

| 2 | Barcelonès | 257,038 | |

| 3 | Barcelonès | 219,547 | |

| 4 | Vallès Occidental | 210,941 | |

| 5 | Vallès Occidental | 206,493 | |

| 6 | Tarragonès | 140,323 | |

| 7 | Segrià | 135,920 | |

| 8 | Maresme | 121,722 | |

| 9 | Barcelonès | 119,717 | |

| 10 | Baix Camp | 107,118 |

Comarques

Comarques are entities composed by the municipalities to manage their responsibilities and services. The current regional division has its roots in a decree of the Generalitat de Catalunya of 1936, in effect until 1939, when it was suppressed by Franco. In 1987 the Government adopted the territorial division again and in 1988 three new comarques were added (Alta Ribagorça, Pla d'Urgell and Pla de l'Estany), and in 2015 was created the last comarca, the Moianès. At present there are 41.

The comarca of Val d'Aran (Aran Valley) has a special status and its autonomous government is named Conselh Generau d'Aran.[57]

Vegueries

The vegueria is a new type of division defined as a specific territorial area for the exercise of government and inter-local cooperation with legal personality. The current Statute of Autonomy states vegueries are intended to supersede provinces in Catalonia, and take over many of functions of the comarques.

The territorial plan of Catalonia (Pla territorial general de Catalunya) provided six general functional areas,[58] but was amended by Law 24/2001, of 31 December, recognizing the Alt Pirineu i Aran as a new functional area differentiated of Ponent.[59] On 14 July 2010 the Catalan Parliament approved the creation of the functional area of the Penedès.[60]

- Alt Pirineu i Aran: Alta Ribagorça, Alt Urgell, Cerdanya, Pallars Jussà, Pallars Sobirà and Val d'Aran.

- Àmbit Metropolità de Barcelona: Baix Llobregat, Barcelonès, Garraf, Maresme, Vallès Oriental and Vallès Occidental.

- Camp de Tarragona: Tarragonès, Alt Camp, Baix Camp, Conca de Barberà and Priorat.

- Comarques gironines: Alt Empordà, Baix Empordà, Garrotxa, Gironès, Pla de l'Estany, La Selva and Ripollès.

- Comarques centrals: Anoia (8 municipalities of 33), Bages, Berguedà, Osona and Solsonès.

- Penedès: Alt Penedès, Baix Penedès, Anoia (25 municipalities of 33) and Garraf.

- Ponent: Garrigues, Noguera, Segarra, Segrià, Pla d'Urgell and Urgell.

- Terres de l'Ebre: Baix Ebre, Montsià, Ribera d'Ebre and Terra Alta.

Economy

In 2014, the regional GDP of Catalonia was €199,797 million (the highest of Spain)[61] and the per capita GDP was €26,996, considerably behind Madrid (autonomous community) (€31,004), the Basque Country (€29,683), and Navarre (€28,124).[62] In that year, the GDP growth was 1.4%.[62] In the last years there has been a negative net relocation rate of companies based in Catalonia moving to other autonomous communities of Spain. In 2014 Calalonia lost 987 companies to other parts of Spain (mainly Madrid), getting only 602 new ones from the rest of the country.[63]

Catalonia's long-term credit rating is BB (Non-Investment Grade) according to Standard & Poor's, Ba2 (Non-Investment Grade) according to Moody's, and BBB- (Low Investment Grade) according to Fitch Ratings.[64][65][66] Catalonia's rating is tied for worst with between 1 and 5 other autonomous communities of Spain, depending on the rating agency.[66]

In the context of the 2008 financial crisis, Catalonia was expected to suffer a recession amounting to almost a 2% contraction of its regional GDP in 2009.[67] Catalonia's debt in 2012 was the highest of all Spain's autonomous communities,[68] reaching €13,476 million, i.e. 38% of the total debt of the 17 autonomous communities.[69]

In 2011, Catalonia ranked the 64th largest country subdivision by GDP (nominal). Catalonia belongs to the organisation Four Motors for Europe.

The distribution of sectors is as follows:[70]

- Primary sector: 3%. The amount of land devoted to agricultural use is 33%.

- Secondary sector: 37% (compared to Spain's 29%)

- Tertiary sector: 60% (compared to Spain's 67%)

The main tourist destinations in Catalonia are the city of Barcelona, the beaches of the Costa Brava in Girona, the beaches of Costa Barcelona from Mataró to Vilanova i la Geltrú and the Costa Daurada in Tarragona. In the Pyrenees there are several ski resorts, near Lleida

On 1 November 2012, Catalonia started charging a tourist tax.[71] The revenue is used to promote tourism, and to maintain and upgrade tourism-related infrastructure.

Many savings banks are based in Catalonia, with 10 of the 46 Spanish savings banks having headquarters in the region. This list includes Europe's premier savings bank, La Caixa.[72] The first private bank in Catalonia is Banc Sabadell, ranked fourth among all Spanish private banks.[73]

The stock market of Barcelona, which in 2004 traded almost €205,000 million, is the second largest of Spain after Madrid, and Fira de Barcelona organizes international exhibitions and congresses to do with different sectors of the economy.

The main economic cost for the Catalan families is the purchase of a home. According to data from the Society of Appraisal on 31 December 2005 Catalonia is, after Madrid, the second most expensive region in Spain for housing: 3,397 €/m² on average (see Spanish property bubble).

Transport

Airports

Airports in Catalonia are owned and operated by Aena (a Spanish Government entity) except two airports in Lleida which are operated by Aeroports de Catalunya (an entity belonging to the Government of Catalonia).

- Barcelona El Prat Airport (BCN, Aena)

- Girona-Costa Brava Airport (GRO, Aena)

- Reus Airport (REU, Aena)

- Lleida-Alguaire Airport (ILD, Aeroports de Catalunya)

- Sabadell Airport (QSA, Aena)

- La Seu d'Urgell Airport (LEU, Aeroports de Catalunya)

Ports

The two main commercial and passenger ports in Catalonia are owned and operated by Puertos del Estado (a Spanish Government entity).

- Port of Barcelona

- Port of Tarragona

The other ports of Catalonia are operated and administered by Ports de la Generalitat, a Catalan Government entity.

Roads

There are 12,000 kilometres (7,500 mi) of roads throughout Catalonia.

The principal highways are AP-7 ![]() (Autopista de la Mediterrània) and A-7 (Autovia de la Mediterrània). They follow the coast from the French border to Valencia, Murcia and Andalusia. The main roads generally radiate from Barcelona. The AP-2

(Autopista de la Mediterrània) and A-7 (Autovia de la Mediterrània). They follow the coast from the French border to Valencia, Murcia and Andalusia. The main roads generally radiate from Barcelona. The AP-2 ![]() (Autopista del Nord-est) and A-2 (Autovia del Nord-est) connect inland and onward to Madrid.

(Autopista del Nord-est) and A-2 (Autovia del Nord-est) connect inland and onward to Madrid.

Other major roads are:

| ID | Itinerary |

|---|---|

| N-II | |

| C-12 | |

| A-16 C-32 | |

| C-16 | |

| C-17 | |

| C-25 | |

| A-26 | |

| C-32 | |

| C-60 |

Public-own roads in Catalonia are either managed by the autonomous government of Catalonia (e.g., C- roads) or the Spanish government (e.g., AP- , A- , N- roads).

Railways

Catalonia saw the first railway construction in the Iberian Peninsula in 1848, linking Barcelona with Mataró. Given the topography most lines radiate from Barcelona. The city has both suburban and inter-city services. The main east coast line runs through the province connecting with the SNCF (French Railways) at Portbou on the coast.

There are two publicly owned railway companies operating in Catalonia: the Catalan FGC that operates commuter and regional services, and the Spanish national RENFE that operates long-distance and high-speed rail services (AVE and Avant) and the main commuter and regional service Rodalies de Catalunya, administered by the Catalan government since 2010.

High-speed rail (AVE) services from Madrid currently reach Lleida, Tarragona and Barcelona. The official opening between Barcelona and Madrid took place 20 February 2008. The journey between Barcelona and Madrid now takes about two-and-a-half hours. A connection to the French high-speed TGV network has been completed, but is awaiting the completion of stations along the route to begin passenger service in April 2013. This new line (currently the LGV Perpignan–Figueres-Vilafant) passes through Girona and Figueres with a tunnel through the Pyrenees. There is a direct train from Barcelona Estació de França to Paris Austerlitz along the older railway tracks.

Demographics

Catalonia covers an area of 32,108 km2 (12,397 sq mi)[1] with an official population of 7,504,008[74] (2015), of which non-Spanish immigrants represent about 19% according to the Spanish Statistics Institute (INE) for 2012.[75]

The Urban Region of Barcelona includes 5,217,864 people and covers an area of 2,268 km2 (876 sq mi), and about 1.7 million people live in a radius of 15 km2 (5.8 sq mi) from Barcelona. The metropolitan area of the Urban Region includes cities such as L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Sabadell, Terrassa, Badalona, Santa Coloma de Gramenet and Cornellà de Llobregat.

In 1900, the population of Catalonia was 1,984,115 people and in 1970 it was 5,107,606.[76] That increase was due to the demographic boom in Spain during the 60s and early 70s and also to the large-scale internal migration from the rural interior of Spain to its industrial cities. In Catalonia that wave of internal migration arrived from several regions of Spain, especially Andalusia, Murcia and Extremadura.

Immigrants from other countries settled in Catalonia in the 1990s and 2000s; a large percentage came from Africa and Latin America, and smaller numbers from Asia and Eastern Europe, often settling in urban centers such as Barcelona and industrial areas.

Languages

According to the linguistic census held by the Government of Catalonia in 2013, Spanish is the most spoken language in Catalonia (46.53% claim Spanish as "their own language"), followed by Catalan (37.26% claim Catalan as "their own language"). In everyday use, 11.95% of the population claim to use both languages equally, whereas 45.92% mainly use Spanish and 35.54% mainly use Catalan. There is a significant difference between the Barcelona metropolitan area (and, to a lesser extent, the Tarragona area), where Spanish is more spoken than Catalan, and the more rural Catalonia, where Catalan clearly prevails over Spanish.[77]

Since the Statute of Autonomy of 1979, Aranese (a dialect of Gascon Occitan) has also been official and subject to special protection in Val d'Aran. This small area of 7,000 inhabitants was the only place where a dialect of Occitan has received full official status. Then, on 9 August 2006, when the new Statute came into force, Occitan became official throughout Catalonia. Occitan is the mother tongue of 22.4% of the population of Val d'Aran.[78] Catalan Sign Language is also officially recognised.[6]

Originating in the historic territory of Catalonia, Catalan has enjoyed special status since the approval of the Statute of Autonomy of 1979 which declares it to be "Catalonia's own language,"[81] a term which signifies a language given special legal status within a Spanish territory, or which is historically spoken within a given region. The other languages with official status are Spanish, which has official status throughout Spain, and Aranese Occitan, which enjoys co-official status with Catalan and Spanish in the Val d'Aran.

Although not considered an "official language" in the same way as Catalan, Spanish, and Aranese, Catalan Sign Language, with about 18,000 users in Catalonia,[82] is granted official recognition and support: "The public authorities shall guarantee the use of Catalan sign language and conditions of equality for deaf people who choose to use this language, which shall be the subject of education, protection and respect."[6]

Under the Franco dictatorship, Catalan was excluded from the public education system and all other official use, so that for example families were not allowed to officially register children with Catalan names.[83] Although never completely banned, Catalan language publishing was severely restricted during the early 1940s, with only religious texts and small-run self-published texts being released. Some books were published clandestinely or circumvented the restrictions by showing publishing dates prior to 1936.[84] This policy was changed in 1946, when unrestricted publishing in Catalan resumed.[85]

Rural–urban migration originating in other parts of Spain also reduced the social use of Catalan in urban areas and increased the use of Spanish. Lately, a similar sociolinguistic phenomenon has occurred with foreign immigration. Catalan cultural activity increased in the 1960s and Catalan classes began thanks to the initiative of associations such as Òmnium Cultural.

After the end of Franco's dictatorship, the newly established self-governing democratic institutions in Catalonia embarked on a long-term language policy to increase the use of Catalan[86] and has, since 1983, enforced laws which attempt to protect and extend the use of Catalan. This policy, known as the "linguistic normalisation" (normalització lingüística in Catalan, normalización lingüística in Spanish) has been supported by the vast majority of Catalan political parties through the last thirty years. Some groups consider these efforts a way to discourage the use of Spanish,[87][88][89][90] whereas some others, including the Catalan government[91] and the European Union[92] consider the policies respectful,[93] or even as an example which "should be disseminated throughout the Union".[94]

Today, Catalan is the main language of the Catalan autonomous government and the other public institutions that fall under its jurisdiction. Usually, basic public education is given in Catalan, except for three hours per week of Spanish medium instruction. However, each teacher has the authority to choose between the Catalan or Spanish depending on their preference. Businesses are required to display all information (e.g. menus, posters) at least in Catalan under penalty of fines. These fines have been challenged in court several times but judicial endorsement have supported the linguistic law. There is no obligation to display this information in either Occitan or Spanish, although there is no restriction on doing so in these or other languages. The use of fines was introduced in a 1997 linguistic law[95] that aims to increase the public use of Catalan and defend the rights of Catalan speakers.

The law ensures that both Catalan and Spanish – being official languages – can be used by the citizens without prejudice in all public and private activities,[96] but primary education can only be taken in Catalan language. The Generalitat uses Catalan in its communications and notifications addressed to the general population, but citizens can also receive information from the Generalitat in Spanish if they so desire.[97] Debates in the Catalan Parliament take place almost exclusively in Catalan and the Catalan public television broadcasts programs only in Catalan given that all state television programming is completely in Spanish.

Due to the intense immigration which Spain in general and Catalonia in particular experienced in the first decade of the 21st century, many foreign languages are spoken in various cultural communities in Catalonia, of which Rif-Berber,[98] Moroccan Arabic, Romanian and Urdu are the most common ones.[99]

Recently, some of these policies have been criticised for trying to promote Catalan by imposing fines on businesses. For example, following the passage of a March 2010 law on Catalan cinema, which establishes that half of the movies shown in Catalan cinemas must be in Catalan, a general strike of 75% of the cinemas took place.[100] These criticisms mostly come from outside Catalonia, especially from conservative, conservative liberal and classical liberal circles of Spanish society. In Catalonia, on the other hand, there is a high social and political consensus on the language policies favoring Catalan, also among Spanish speakers and speakers of other languages.[101][101][102][103][104] The United Nations Human Rights Committee ruled in 1993 against similar policies in Quebec stating that "A State may choose one or more official languages but it may not exclude outside the spheres of public life, the freedom to express oneself in a certain language".[105] The US government, based on its Human Rights Report,[106] questions the linguistic law [107] and reports irregularities of the rights of the Spanish speakers in Catalonia. On the other hand, such organisations as Plataforma per la Llengua reported different violations of the linguistic rights of the Catalan speakers in Catalonia and the other Catalan-speaking territories in Spain, most of them caused by the institutions of the Spanish government in these territories.[108]

In Catalonia, the Catalan language policy has been challenged by some Catalan intellectuals like Albert Boadella. Since 2006, the liberal Citizens - Party of the Citizenry, currently the main opposition party, has been one of the most consistent critics of the Catalan language policy within Catalonia. The local Catalan branch of the People's Party has a more ambiguous position on the issue: on one hand, it demands a bilingual Catalan–Spanish education and a more balanced language policy that would defend Catalan without favoring it over Spanish,[109] whereas on the other hand, a few local PP politicians have supported in their municipalities measures privileging Catalan over Spanish[110] and it has defended some aspects of the official language policies, sometimes against the positions of its colleagues from other parts of Spain.[111]

Culture

Art and architecture

Monuments and World Heritage Sites

_(_UNESCO_World_Heritage_Site)._Barcelona%2C_Catalonia%2C_Spain.jpg)

There are several UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Catalonia:

- Archaeological Ensemble of Tarraco, Tarragona

- Catalan Romanesque Churches of the Vall de Boí, Lleida province

- Poblet Monastery, Poblet, Tarragona province

- Works of Lluís Domènech i Montaner:

- Palau de la Música Catalana, Barcelona

- Hospital de Sant Pau, Barcelona

- Works of Antoni Gaudí:

- Sagrada Família, Barcelona

- Parc Güell, Barcelona

- Palau Güell, Barcelona

- Casa Milà (La Pedrera), Barcelona

- Casa Vicens, Barcelona

- Casa Batlló, Barcelona

- The Church of Colònia Güell, Santa Coloma de Cervelló

Literature

Music and dance

The sardana is the most characteristic Catalan popular dance, other groups also practice Ball de bastons, moixiganga, galops or jota in the southern part. Musically, the Havaneres are also characteristic in some marine localities of the Costa Brava especially during the summer months when these songs are sung outdoors accompanied by a cremat of burned rum. Other music styles are Catalan rumba, Catalan rock and Nova Cançó.

Cinema

Philosophy

Sport

Symbols

Catalonia has its own representative and distinctive symbols such as:[112]

- The flag of Catalonia, called the Senyera, is a vexillological symbol based on the heraldic emblem of Counts of Barcelona and the coat of arms of the Crown of Aragon, which consists of four red stripes on a golden background. It has been an official symbol since the Statute of Catalonia of 1932.

- The National Day of Catalonia[113] is on the Eleventh of September, and it is commonly called La Diada. It commemorates the 1714 Siege of Barcelona defeat during the War of the Spanish Succession.

- The national anthem of Catalonia is Els Segadors and was written in its present form by Emili Guanyavents in 1899. The song is official by law from 25 February 1993.[114][115] It is based on the events of 1639 and 1640 during the Catalan Revolt.

- St George's Day (Catalan: Diada de Sant Jordi) is widely celebrated in all the towns of Catalonia on 23 April, and includes an exchange of books and roses between couples or family members.

Festivals and public holidays

Castells are one of the main manifestations of Catalan popular culture. The activity consists in constructing human towers by competing colles castelleres (teams). This practice originated in the southern part of Catalonia during the 18th century. The tradition of els Castells i els Castellers was declared Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO in 2010.

In the greater celebrations other elements of the Catalan popular culture are usually present: the parades of gegants (giants) and correfocs of devils and firecrackers. Another traditional celebration in Catalonia is La Patum de Berga, declared Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO on 25 November 2005.[116]

In addition to traditional local Catalan culture, traditions from other parts of Spain can be found as a result of migration from other regions, for instance the celebration of the Andalusian Feria de Abril in Catalonia.

On 28 July 2010, Catalonia became the second Spanish territory, after the Canary Islands, to forbid bullfighting. The ban, which went into effect on 1 January 2012, had originated in a popular petition supported by over 180,000 signatures.[117]

Image gallery

- Catalonia gallery

-

Satellite view of Catalonia

-

Llívia exclave

-

Val de Ruda, Val d'Aran

-

Park Güell, Barcelona

-

Cathedral of Saint Eulàlia, Barcelona

-

.jpg)

Borago officinalis near Font de Tita, El Perelló

Twinning and covenants

See also

- Index of Catalonia-related articles

- Outline of Catalonia

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Pronunciation:

- 1 2 3 4 In French, the name of Catalunya (Catalonia) is rendered as Catalogne ([ka.ta.loɲ]).

- ↑ According to the current statute of Autonomy of Catalonia and under the framework of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, Catalonia is defined as a "nationality" within the Spanish nation. In 2006, the Catalan people were defined as a nation by the original 2006 Statute of Autonomy prior to been rejected and modified by the Constitutional Court of Spain. [3]

Fragment of the Preamble of the original Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia:

"El Parlament de Catalunya, recollint el sentiment i la voluntat de la ciutadania de Catalunya, ha definit Catalunya com a "nació" d'una manera àmpliament majoritària.'[4]

References

- 1 2 "Indicadors geogràfics. Superfície, densitat i entitats de població: Catalunya". Statistical Institute of Catalonia. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- ↑ National Statistics Office (Spain's GDP and GRP), National Statistics Office. GDP Figures of Spanish autonomous communities and provinces 2008–2012.

- ↑ "Court to reject 'nation' in Catalonia statute".

- ↑ "Preàmbul. Estatut d'autonomia de Catalunya 2006" (in Catalan). Generalitat de Catalunya.

- ↑ "First article of the Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia. "''Catalonia, as a nationality, exercises its self-government constituted as an autonomous community..."''". Gencat.cat. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia (2006), Articles 6, 50 - BOPC 224" (PDF). Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Enciclopèdia Catalana online: Catalunya ("Geral de Cataluign, Raimundi Catalan and Arnal Catalan appear in 1107/1112") (in Catalan) Archived 24 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Maximiano García Venero (7 July 2006). Historia del nacionalismo catalán: 2a edición. Ed. Nacional. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Ulick Ralph Burke (1900). A history of Spain from the earliest times to the death of Ferdinand the Catholic. Longmans, Green, and co. p. 154.

- ↑ The Sarmatians: 600 BC-AD 450 (Men-at-Arms) by Richard Brzezinski and Gerry Embleton, 19 August 2002.

- ↑ "La formació de Catalunya". Gencat.cat. Archived from the original on 15 December 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ El Misteri de la Paraula Cathalunya.

- ↑ "La Catalogne: son nom et ses limites historiques, Histoire de Roussillon". Mediterranees.net. 22 March 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ Feldhausen, Ingo (2010). Sentential Form and Prosodic Structure of Catalan. John Benjamins B.V. p. 5. ISBN 9789027255518.

- ↑ "Las Cortes Catalanas y la primera Generalidad medieval (s. XIII-XIV)". Retrieved 21 January 2013.

- ↑ According to John Huxtable Elliott, "Between 1347 and 1497 the Principality [Catalonia] had lost 37% of its inhabitants, and was reduced to a population of something like 300,000." John Huxtable Elliott (1984). The revolt of the Catalans: a study in the decline of Spain (1598–1640). Cambridge University Press. p. 26. ISBN 0-521-27890-2.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica online. "Charles V". Retrieved October 2012.

- ↑ Preston, Paul. (2012). The Spanish Holocaust. Harper Press. London p.493

- ↑ Ross. Cultural Contestation in Ethnic Conflict. Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-139-46307-2.

- ↑ Thomas, Earl W (March 1962), "The Resurgence of Catalan", Hispania 45 (1), pp. 43–48, doi:10.2307/337523

- ↑ elpais

.com /m /elpais /2015 /11 /05 /inenglish /1446747744 _752094 .html - ↑ www

.euroweeklynews .com /3 .0 .15 /news /on-euro-weekly-news /spain-news-in-english /134935-constitutional-court-rejects-blocking-motion-on-catalan-independence - ↑ El Relleu, "Grup Enciclopèdia Catalana". Retrieved 26 December 2007

- ↑ Gran Enciclopedia Catalana (ed.). "Catalunya: El clima i la hidrografia". l'Enciclopèdia (in Catalan). Barcelona.

- ↑ Catalunya. MSN Encarta

- ↑ "Beginnings of the autonomous regime, 1918–1932". Gencat.net. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "The republican Government of Catalonia, 1931–1939". Gencat.net. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Title IV. Powers (articles 110–173)of the 2006 Statute". Gencat.cat. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Centrifugal Spain: Umbrage in Catalonia". The Economist. 24 November 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- 1 2 "CEO Public Opinion Poll covering, among others, nationalist opinions" (PDF). ceo.gencat.cat. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- ↑ "La Vanguardia poll".

- ↑ http://www.uoc.edu/portal/_resources/CA/documents/sala_premsa/noticies/Dossier_premsa_Diagnxstic_Catalunya-_Espanya.pdf

- ↑ "El 42% de los catalanes dice que quiere que Cataluña sea independiente". Cadenaser.com. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Racalacarta.com. Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "El apoyo a la independencia remite y cae al 40%". Lavanguardia.es. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ "Referèndum per la independència de Catalunya – Centre d'Estudis d'Opinió". Einesceo.cat. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ "Baròmetre d'Opinió" (in Catalan). Center for Public Opinion Studies. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ "Spain's Catalonia region in symbolic independence vote". BBC News. 14 December 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ ""Unas 600.000 personas en la manifestación independentista". La Vanguardia de Catalunya". Lavanguardia.com. 14 September 2012. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ Pi, Jaume (11 September 2012). "Masiva manifestación por la independencia de Catalunya". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ↑ Abend, Lisa (11 September 2012). "Spain Barcelona Warns Madrid: Pay Up, or Catalonia Leaves Spain". TIME. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- ↑ Xavier Mir i Oliveras (2007). Vostè Té Un Problema i Aquest Problema Es Diu PSC. Lulu.com. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-84799-752-4.

- ↑ "Resultats provisionals 27S". gencat.cat. Generalitat de Catalunya. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- ↑ "First article of the Statute of Autonomy of Catalunya". Gencat.net. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Constitución Española, Título Preliminar. Archived 13 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Europa Press/Madrid (1 December 1997). "Admitidos los recursos de Aragón, Valencia y Baleares contra el Estatuto catalán.". Hoy.es. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ El País (29 June 2010). "Cuatro años de encarnizada batalla política.". El País. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "Ni un retoque en 74 artículos recurridos". El País. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ "Catalonia 'is not a nation' 10 July 2010". Edinburgh: News.scotsman.com. 10 July 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ "Is Catalonia a nation or a nationality, or is Spain the only nation in Spain?". Matthewbennett.es. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ Fiona Govan in Madrid 1:59PM BST 29 June 2010 (29 June 2010). "Catalonia can call itself a 'nation', rules Spain's top court 29 Jun 2010". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ "A nationality, not a nation Jul 1st 2010". Economist.com. 1 July 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ "Legislació civil catalana". Civil.udg.es. 20 July 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Padró municipal d'habitants. Xifres Oficials. Recomptes. Any 2010". idescat. Archived from the original on 13 November 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ↑ "Actualització INE 2009". Ine.es. 28 May 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ "Ley 16/1990, de 13 de julio, sobre el régimen especial del Valle de Arán.". Noticias Jurídicas. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ↑ "Pla territorial general de Catalunya". Generalitat de Catalunya. Archived from the original on 4 July 2010. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ↑ Aprovació del Pla territorial parcial de l'Alt Pirineu i Aran. Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "El Parlament reconeix l'àmbit funcional del Penedès". Avui. 15 July 2010.

- ↑

- 1 2

- ↑ companiesmmExpansión: relocation of companiesTemplate:Retrieved: 8 May 2015

- ↑ "S&P mantiene la deuda de Cataluña en "bono basura"". Expansión (Unidad Editorial). 17 April 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ↑ "Standard & Poor's degrada la calificación de Catalunya a 'bono basura'". La Vanguardia Economía (Javier Godó). La Vanguardia. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- 1 2 "Rating: Calificación de la deuda de las Comunidades Autónomas". Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ↑ "BBVA no descarta que la economía catalana caiga un 2% • ELPAÍS.com". Elpais.com. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Spanish Region of Catalonia: Using Debt to Get Rich". CNBC News. Retrieved 14 October 2013.

- ↑ Financial Crisis (25 May 2012). ""Catalonia calls for help from central government to pay debts". The Telegraph". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- ↑ "Structural Funds programmes in Catalonia – (2000–2006)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Catalonia Tourist Tax". Costa Brava Tourist Guide. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ "Ranking of Savings Banks" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Profile of "Banc Sabadell" in Euroinvestor". Euroinvestor.es. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ Statistics of the Generalitat of Catalonia

- ↑ "Instituto Nacional de Estadística, padrón por municipios, 2012". Ine.es. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Gencat.net. (in Catalan) Archived 13 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Idescat. Dades demogràfiques i de qualitat de vida". Idescat.cat. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Enquesta d'usos lingüístics de la població 2008, cap. 8. La Val d’Aran.

- ↑ Veny 1997, pp. 9–18.

- ↑ Moran 2004, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ "Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia (Article 6)". Gencat.cat. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Catalan Sign Language". Ethnologue.com. 19 February 1999. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ Joan Miralles i Montserrat; Josep Massot i Muntaner (2001). Entorn de la histáoria de la llengua. L'Abadia de Montserrat. p. 72. ISBN 978-84-8415-309-2.

- ↑ Pelai Pagès i Blanch (2004). Franquisme i repressió: la repressió franquista als països catalans 1939–1975. Universitat de València. ISBN 978-84-370-5924-2. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ Pelai Pagès i Blanch (2004). Franquisme i repressió: la repressió franquista als països catalans (1939–1975). Universitat de València. ISBN 978-84-370-5924-2.

- ↑ M. Teresa Turell (2001). Multilingualism in Spain: Sociolinguistic and Psycholinguistic Aspects of Linguistic Minority Groups. Multilingual Matters. ISBN 978-1-85359-491-5. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Belen Parra (5 June 2008). "Diario El Mundo, Spanish Only". Medios.mugak.eu. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Diario El Imparcial, Spanish Only". Elimparcial.es. 26 July 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Diario Periodista Digital, Spanish Only". Blogs.periodistadigital.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Diario Periodista Digital, Spanish Only". Blogs.periodistadigital.com. Archived from the original on 17 July 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Page 13: Catalan Deputy of Education Ernest Maragall declares respect from the Catalan Government to Spanish language and to everyone's rights (in Calatan)

- ↑ EU takes Basque Country, Galicia, Catalonia and Valencia as examples of bilingualism. Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The President Montilla promises to look after the use and respect both for Spanish and Catalan languages

- ↑ "High Level Group on Multilingualism – Final Report: from the Commission of the European Communities in which Catalan immersion is taken as an example which "should be disseminated throughout the Union" (page 18)." (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Catalonia's linguistic law". 0.gencat.cat. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Second article of Catalonia's linguistic law". 0.gencat.cat. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Ninth article of Catalonia's Linguistic Law". 0.gencat.cat. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "DESCOBRIR LES LLENGÜES DE LA IMMIGRACIÓ" (PDF). University of Barcelona. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Árabe y urdu aparecen entre las lenguas habituales de Catalunya, creando peligro de guetos.". Europapress.es. 29 June 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Louis @ (25 March 2010). "Cinema law: rude case to not dub and subtitle all films in Catalan". Cafebabel.co.uk. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- 1 2 "Presència". Presencia.cat. 26 January 2014. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑

- ↑ "normalitzacio.cat". normalitzacio.cat. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Joan Albert Argenter, ed. (1991). Debat sobre la normalització lingüística: Ple de l'Institut d'Estudis Catalans (18 d'abril de 1990). Institut d'Estudis Catalans. p. 24. ISBN 978-84-7283-168-1.

- ↑ Quebec Language Laws Bill 101, CBC News Online, 30 March 2005

- ↑ Human Rights Report: Spain

- ↑ USA questions the linguistic policy of the Basque Coutry, Catalonia and the Balearic Islands

- ↑ "La Plataforma per la Llengua denuncia en un informe 40 casos greus de discriminació lingüística a les administracions públiques ocorreguts els darrers anys". Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ "Alicia Sánchez-Camacho responde en 'Tengo una pregunta para usted'". YouTube. 11 November 2010. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ Regió7. "El PPC va votar a favor d´un reglament sobre el català - Regió7 :: El Diari de la Catalunya Central". Regio7.cat. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ "Sánchez-Camacho rebutja la postura inicial de Bauzá de derogar la llei de Normalització Lingüística a les Illes Balears". 3cat24.cat. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- ↑ "Statute of Catalonia (Article 8)". Gencat.net. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Law 1/1980 where the Parlamient of Catalonia declares that 11th of September is the National Day of Catalonia". Noticias.juridicas.com. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ "Law 1/1993 National Anthem of Catalonia". Noticias.juridicas.com. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Law 1/1993 in the BOE

- ↑ Patum de Berga. Archived 27 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ The Press Association: Catalonia votes to ban bullfighting, 28 July 2010.

- ↑ "Firman acuerdo de colaboración gobierno de NL y Cataluña, España | Info7 | Nuevo León". Info7. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Firman NL y Cataluña intercambio estratégico | Info7 | Nuevo León". Info7.mx. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ José Lebeña Acebo. "VIDEO: Nuevo León y Cataluña, ¿tierras hermanas? – Publimetro". Publimetro.com.mx. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ http://soir.senate.ca.gov/scr71

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Generalitat de Catalunya (Government of Catalonia)

- Statute of Autonomy of Catalonia

- Statistical information from Idescat (Catalan Institute of Statistics)

- Association of Catalan Language Writers

- Catalan Encyclopaedia

- Catalonia Spain: A Catalonia Weblog.

- A guide to the natural history of Catalonia

- The Spirit of Catalonia. Digital edition of the 1946 book by Oxford Professor Dr. Josep Trueta.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png)

detalle.jpg)

_01.jpg)

.jpg)