Reserve requirement

The reserve requirement (or cash reserve ratio) is a central bank regulation employed by most, but not all, of the world's central banks, that sets the minimum fraction of customer deposits and notes that each commercial bank must hold as reserves (rather than lend out). These required reserves are normally in the form of deposits made with a central bank, or cash stored physically in the bank vault (vault cash).

The required reserve ratio is sometimes used as a tool in monetary policy, influencing the country's borrowing and interest rates by changing the amount of funds available for banks to make loans with.[1] Western central banks rarely alter the reserve requirements because it would cause immediate liquidity problems for banks with low excess reserves; they generally prefer to use open market operations (buying and selling government-issued bonds) to implement their monetary policy. The People's Bank of China uses changes in reserve requirements as an inflation-fighting tool, and raised the reserve requirement ten times in 2007 and eleven times since the beginning of 2010.

An institution that holds reserves in excess of the required amount is said to hold excess reserves.

Effects on money supply

The conventional view

The economic theory that a reserve requirement can act as a tool of monetary policy is frequently found in economics textbooks. The higher the reserve requirement is set, the theory supposes, the less funds banks will have to loan out , leading to lower money creation and perhaps ultimately to higher purchasing power of the money previously in use. The effect is multiplied, because money obtained as loan proceeds can be re-deposited; a portion of those deposits may again be loaned out, and so on. The effect on the money supply is governed by the following formulas:

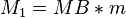

: definitional relationship between monetary base MB (bank reserves plus currency held by the non-bank public) the narrowly defined money supply,

: definitional relationship between monetary base MB (bank reserves plus currency held by the non-bank public) the narrowly defined money supply,  ,

,

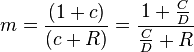

: derived formula for the money multiplier m, the factor by which lending and re-lending leads

: derived formula for the money multiplier m, the factor by which lending and re-lending leads  to be a multiple of the monetary base:

to be a multiple of the monetary base:

where notationally,

the currency ratio: the ratio of the public's holdings of currency (undeposited cash) to the public's holdings of demand deposits; and

the currency ratio: the ratio of the public's holdings of currency (undeposited cash) to the public's holdings of demand deposits; and

the total reserve ratio (the ratio of legally required plus non-required reserve holdings of banks to demand deposit liabilities of banks).

the total reserve ratio (the ratio of legally required plus non-required reserve holdings of banks to demand deposit liabilities of banks).

However, in the United States (and other countries except Brazil, China, India, Russia), the reserve requirements are generally not frequently altered to implement monetary policy because of the short-term disruptive effect on financial markets.

The endogenous money view

Some economists dispute the conventional theory of the reserve requirement. Criticisms of the conventional theory are usually associated with theories of endogenous money.

Jaromir Benes and Michael Kumhof of the IMF Research Department report that the “deposit multiplier“ of the undergraduate economics textbook, where monetary aggregates are created at the initiative of the central bank, through an initial injection of high-powered money into the banking system that gets multiplied through bank lending, turns the actual operation of the monetary transmission mechanism on its head. Most times when banks ask for replenishment of depleted reserves, the central bank obliges.[2] Reserves therefore impose no constraints as the deposit multiplier is simply, in the words of Kydland and Prescott (1990), a myth. And because of this, private banks are almost fully in control of the money creation process.[3]

Required reserves

United States

In the United States, a reserve requirement[4] (or liquidity ratio) is a minimum value, set by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, of the ratio of required reserves to some category of deposits held at depository institutions (e.g., commercial bank including US branch of a foreign bank, savings and loan association, savings bank, credit union). The only deposit categories currently subject to reserve requirements are transactions accounts, mainly checking accounts. The total amount of all net transaction accounts (total transaction accounts less amounts due from other banks and less cash items in the process of collection) held in US depository institutions, plus US currency held by the nonbank public, is called M1.

A depository institution can satisfy its reserve requirements by holding either vault cash[5] or reserve deposits. An institution that is a member of the Federal Reserve System must hold its reserve deposits at a Federal Reserve Bank. Nonmember institutions can elect to hold their reserve deposits at a member institution on a pass-through basis.[6]

A depository institution's reserve requirements vary by the dollar amount of net transaction accounts held at that institution. Effective January 23, 2014, institutions with net transactions accounts:

- Of less than $15.2 million have no minimum reserve requirement;

- Between $15.2 million and $110.2 million must have a liquidity ratio of 3% of liabilities;

- Exceeding $110.2 million must have a liquidity ratio of 10% of liabilities.[6]

The threshold monetary amounts are recalculated annually according to a statutory formula.

Effective December 27, 1990, a liquidity ratio of zero has applied to CDs, savings deposits, and time deposits, owned by entities other than households, and the Eurocurrency liabilities of depository institutions. Deposits owned by foreign corporations or governments are currently not subject to reserve requirements.[6]

When an institution fails to satisfy its reserve requirements, it can make up its deficiency with reserves borrowed either from a Federal Reserve Bank, or from an institution holding reserves in excess of reserve requirements. Such loans are typically due in 24 hours or less.

An institution's overnight reserves, averaged over some maintenance period, must equal or exceed its average required reserves, calculated over the same maintenance period. If this calculation is satisfied, there is no requirement that reserves be held at any point in time. Hence reserve requirements play only a limited role in money creation in the USA - and since quantitative easing began in 2008, they have been even less important, as an enormous glut of excess reserves now exists (over the whole system; though, in theory, individual banks may still run into temporary shortfalls).

The International Banking Act of 1978 requires branches of foreign banks operating in the US to follow the same required reserve ratio standards.[7][8]

Countries without reserve requirements

Canada, the UK, New Zealand, Australia and Sweden have no reserve requirements.

This does not mean that banks can - even in theory - create money without limit. On the contrary: banks are constrained by capital requirements, which are arguably more important than reserve requirements even in countries that have reserve requirements.

It also does not mean that a commercial bank's overnight reserves can become negative, in these countries. On the contrary: the central bank will always step in to lend the necessary reserves if necessary so that this does not happen: this is sometimes described as "defending the payment system". Historically, a central bank might once have run out of reserves to lend and so have had to suspend redemptions, but this cannot happen anymore to modern central banks because of the end of the gold standard worldwide, which means that all nations use a fiat currency.

A zero reserve requirement cannot be explained by a theory that holds that monetary policy works by varying the quantity of money using the reserve requirement.

Even in the United States, which retains formal (though now mostly irrelevant) reserve requirements, the notion of controlling the money supply by targeting the quantity of base money fell out of favour many years ago, and now the pragmatic explanation of monetary policy refers to targeting the interest rate to control the broad money supply.

United Kingdom

In the UK the term clearing banks is sometimes used, meaning banks that have direct access to the clearing system. However, for the purposes of clarity, the term commercial banks will be used for the remainder of this section.

The Bank of England, which is the central bank for the entire United Kingdom, previously held to a voluntary reserve ratio system, with no minimum reserve requirement set. In theory, this meant that commercial banks could retain zero reserves. However, the average cash reserve ratio across the entire United Kingdom banking system was higher during that period, at about 0.15% as of 1999.[9]

From 1971 to 1980, the commercial banks all agreed to a reserve ratio of 1.5%. However, in 1981 this requirement was abolished.[9]

From 1981 to 2009, each commercial bank set out its own monthly voluntary reserve target in a contract with the Bank of England. Both shortfalls and excesses of reserves relative to the commercial bank's own target over an averaging period of one day[9] would result in a charge, incentivising the commercial bank to stay near its target, a system known as reserves averaging.

Upon the parallel introduction of quantitative easing and interest on excess reserves in 2009, banks were no longer required to set out a target, and so were no longer penalised for holding excess reserves; indeed, they were proportionally compensated for holding all their reserves at the Bank Rate (the Bank of England now uses the same interest rate for its bank rate, its deposit rate and its interest rate target).[10] Indeed, in the absence of an agreed target, the concept of excess reserves does not really apply to the Bank of England any more, so it is technically incorrect to call its new policy "interest on excess reserves".

Canada

Canada abolished its reserve requirement in 1992.[9]

Other countries

Other countries have required reserve ratios (or RRRs) that are statutorily enforced:[11]

| Country | Required reserve (in %) | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | None | Statutory Reserve Deposits abolished in 1988, replaced with 1% Non-callable Deposits[12] |

| New Zealand | None | |

| Sweden | None | Effective April 1, 1994[13] |

| Eurozone | 1.00 | Effective January 18, 2012.[14] Down from 2% between January 1999 and January 2012. |

| Czech Republic | 2.00 | Since October 7, 2009 |

| Hungary | 2.00 | Since November 2008 |

| South Africa | 2.50 | |

| Switzerland | 2.50 | |

| Latvia | 3.00 | Just after the Parex Bank bailout (24.12.2008), Latvian Central Bank decreased the RRR from 7% (?) down to 3%[15] |

| Poland | 3.50 | as of 31 dec 2010 [16] |

| Romania | 10.00 | as of 30 jan 2013 for lei. And 16% for foreign currency[17] |

| Russia | 4.00 | Effective April 1, 2011, up from 2.5% in January 2011.[18] |

| Chile | 4.50 | |

| India | 4.00 | Jun2 2015, as per RBI.[19] |

| Bangladesh | 6.00 | Raised from 5.50. Effective from 15 December 2010 |

| Lithuania | 6.00 | |

| Nigeria | 20.00 | Raised from 15.00. Effective from 25 November 2014[20] |

| Pakistan | 5.00 | Since November 1, 2008 |

| Taiwan | 7.00 | [21] |

| Turkey | 8.50 | Since February 19, 2013 |

| Jordan | 8.00 | |

| Zambia | 8.00 | |

| Burundi | 8.50 | |

| Ghana | 9.00 | |

| Israel | 9.00 | the Required Reserve Ratio is called Minimum Capital Ratio[22] |

| Mexico | 10.50 | |

| Sri Lanka | 8.00 | With effect from 29 April 2011. 8% of total rupee deposit liabilities. |

| Bulgaria | 10.00 | Banks shall maintain minimum required reserves to the amount of 10% of the deposit base (effective from December 1, 2008) with two exceptions (effective from January 1, 2009): 1. on funds attracted by banks from abroad: 5%; 2. on funds attracted from state and local government budgets: 0%.[23] |

| Croatia | 14.00 | Down from 17%, effective from 2009-01-14[24] |

| Costa Rica | 15.00 | |

| Malawi | 15.00 | |

| Nepal | 5.00 | From the monetary policy announcement for FY 2011/12 CRR reduced from 5.5% to 5% |

| Hong Kong | None | [25] |

| Brazil | 20.00 | Up from 15%, effective from 2010-12-06 - Ratio is for requirement on term deposits.[26] RRR for foreign currency positions increased to 43.00 on 2010 July 15 |

| China | 18.50 | China cuts bank reserves again to counter slowdown as of 20 April 2015. Chinese Banks [27] |

| Tajikistan | 20.00 | |

| Suriname | 25.00 | Down from 27%, effective from 2007-01-01[28] |

| Lebanon | 30.00 | |

Historical changes in reserve ratios

In some countries, the cash reserve ratios have decreased over time; in some countries they have increased:[29]

| Country | 1968 | 1978 | 1988 | 1998 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 20.5 | 15.9 | 5.0 | 3.1 |

| Turkey | 58.3 | 62.7 | 30.8 | 18.0 |

| Germany | 19.0 | 19.3 | 17.2 | 11.9 |

| United States | 12.3 | 10.1 | 8.5 | 10.3 |

| India[30] | 3 | 6 | 10 | 10-11 |

(Ratios are expressed in percentage points.)

See also

- Bank regulation

- Basel accords

- Capital Requirement

- Capital adequacy ratio

- Excess reserves

- Financial repression

- Fractional-reserve banking

- Full-reserve banking

- Islamic banking

- Monetary policy of central banks

- Money creation

- Money supply

- Negative interest on excess reserves

- Statutory Liquidity Ratio

- Tier 1 capital

- Tier 2 capital

References

- ↑ Central Bank of Russia

- ↑ Benes, Jaromir, and Michael Kumhof. The chicago plan revisited. International Monetary Fund, 2012. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12202.pdf

- ↑ Benes, Kumhof. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2012/wp12202.pdf

- ↑ See generally Regulation D, at 12 C.F.R. sec. 204.5.

- ↑ See 12 C.F.R. sec. 204.2(k).

- 1 2 3 FRB: Reserve Requirements

- ↑ Ahorny, Joseph; Saunders, Anthony; Swary, Itzhak (1985). "The Effects of the International Banking Act on Domestic Bank Profitability and Risk". Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking (JSTOR) 17: 493–506. JSTOR 1992444.

- ↑ "International Banking Act of 1978". Banking Law 101.

- 1 2 3 4 Jagdish Handa (2008). Monetary Economics (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 347.

- ↑ "Sterling Operations - Implementation of Monetary Policy". Bank of England. Retrieved 26 August 2013.

- ↑ Lecture 8, Slide 4: "Central Banking and the Money Supply" from the presentation Monetary Macroeconomics by Dr. Pinar Yesin, University of Zurich, based on 2003 survey of CBC participants at the Study Center Gerzensee

- ↑ "Inquiry into the Australian Banking Industry, Reserve Bank of Australia, January 1991

- ↑ Lotsberg, Kari Penning- & valutapolitik, p. 45-47, 1994:2

- ↑ <en> European Central Bank, minimum reserve requirements

- ↑ "Minimum Reserve Ratio". Bank of Latvia. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ Narodowy Bank Polski - Internet Information Service

- ↑ Reserve requirements, National Bank of Romania

- ↑ Central bank of Russia Required reserve ratio on credit institutions' liabilities to non-resident has been raised to 4.0%

- ↑ ndtv.com

- ↑ http://businessdayonline.com/2014/11/banks-squeezed-further-as-n40bn-may-vanish-from-industry-wide-profits/#.VHbDB51fqUk

- ↑ Liquidity ratio and liquid reserves of deposit money banks. Data released by Taiwan's central bank in October 2010.

- ↑ "Minimum capital ratio" (PDF). Bank of Israel. Retrieved 2010-12-29.

- ↑ "Ordinance No. 21 of the BNB on the Minimum Required Reserves Maintained with the Bulgarian National Bank by Banks" (PDF). Bulgarian National Bank.

- ↑ Decision on Reserve Requirements, Croatian National Bank (in Croatian)

- ↑ "Central banks' exit strategies from quantitative easing". Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ↑ Business week - Brazil reserve requirement raise

- ↑ http://www.cnbc.com/id/102599470

- ↑ "Reserve base en Kasreserve". Centrale Bank van Suriname. Retrieved 2009-12-21.

- ↑ IMF Financial Statistic Yearbook

- ↑ Chronology of Bankrate, CRR and SLR Changes, Reserve Bank of India

External links

- Title 12 of the Code of Federal Regulations (12CFR) PART 204--RESERVE REQUIREMENTS OF DEPOSITORY INSTITUTIONS (REGULATION D) (See Section §204.4 for current reserve requirements.)

- Reserve Requirements - Fedpoints - Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- Reserve Requirements - The Federal Reserve Board

- Hussman Funds - Why the Federal Reserve is Irrelevant - August 2001

- Don't mention the reserve ratio