Carvel (boat building)

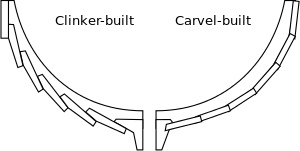

Carvel built or carvel planking is a method of boat building where hull planks are fastened edge to edge, gaining support from the frame and forming a smooth surface.

In contrast with clinker built hulls, where planked edges overlap, carvel construction gives a stronger hull, capable of taking a variety of full-rigged sail plans, albeit one of greater weight. In addition, it enables greater length and breadth of hull and superior sail rigs because of its strong framing, and is one of the critical developments that led to the preeminence of Western European seapower during the Age of Sail and beyond.

Carvel developed through transition from the age-old Mediterranean mortise and tenon joint method to the skeleton-first hull building technique, which gradually emerged in the medieval period.

History

The first carvel-built ships were the carracks and caravels of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Both were developed in Iberia and were sailed by the kingdoms of Portugal and Spain in the early trans-oceanic voyages of the Age of Discovery. At the same time as their appearance, the centuries-long battles to expel the Muslims from Iberia were gradually swinging to the Christian side, represented by the Kingdom of Aragon and the Kingdom of Castile, which were not united into Spain until the time of Christopher Columbus. Their invention is generally credited to the Portuguese people, who first explored the Atlantic islands and south along the coast of Africa, searching for a trade route to the Far East in order to avoid the costly middlemen of the Eastern Mediterranean civilizations who sat upon the routes of the spice trade. Spices, in the era, were expensive luxuries and were used medicinally.

Relationship between clinker and carvel

The clinker form of construction is often linked in people's minds with the Vikings, who used this method to build their famous longships from riven timber (split wood) planks. Clinker is the British term. It is known as lapstrake in North America. In general, the languages of other countries where the method was current use some version of the word clinker.

The smoother surface of a carvel boat gives the impression at first sight that it is hydrodynamically more efficient. The lands of the planking are not there to disturb the streamline. This distribution of relative efficiency between the two forms of construction is an illusion: For given hull strength, the clinker boat is lighter, because it has far less heavy timber framing. It, therefore, displaces less water, so it has less to push aside while moving. The reduced displacement could be used to make the lines finer so as to make the passage through the water easier still. Of course, displacement was increased as cargo was loaded, but still, the clinker vessel had the advantage in efficiency, as the structure was less bulky; therefore, for a given internal volume, there was a smaller external one. That means that a bulkier cargo could be carried if need be, given sufficient freeboard. Clinker-built vessels are, however, not well suited to most types of sailing rigs, because they lack the internal rigidity to anchor the vessel's stays against the transverse forces generated by sailing into or across the wind with either lateen or sloop rigging methods. They also lack the internal strength to support a center-board, as well as a deep keel, drastically limiting their ability to sail across or close to the wind.

Additionally, the clinker design created a vessel that could twist and flex relative to the long axis of the vessel (from bow to stern). This gave it an advantage in North Atlantic rollers so long as the vessel was small in overall displacement. Increasing the beam, due to the light nature of the method, did not commensurately increase the vessel's survivability under the torsional forces of rolling waves; greater beam widths may, in fact, have made the resultant vessels more vulnerable. Thus, the greater rigidity of carvel-built construction became necessary for larger non-coastal cargo vessels, as the twisting forces grew in proportion to displaced (or cargo) weight. The physics of this imposed an upper limit on the size of clinker-built vessels. Later carvel-built sailing vessels exceeded the maximum size of clinker-built ships several times over. However, clinker construction remains to this day a valuable method of construction for small wooden vessels.

A number of boat building texts are available that describe the carvel planking process in detail.[1]

Modern carvel methods

Traditional carvel methods leave a small gap between each plank that in the past was filled with any suitable soft, flexible, fibrous material, sometimes combined with a thick binding substance. This caulking would gradually wear out and the hull would leak. Likewise, when the boat was beached for a length of time, the planks would dry and shrink, so when first refloated, the hull would leak badly unless recaulked — a very time-consuming and physically demanding job. The modern variation is to use much narrower planks that are edge-glued instead of caulked. With modern power sanders a much smoother hull is produced, as all the small ridges between the planks can be removed. This method started to become more common in the 1960s with the more widespread availability of waterproof glues, such as resorcinol (red glue) and then epoxy resin.[2] Modern waterproof glues, especially epoxy resin, have caused revolutionary changes in both carvel and clinker style construction. Whereas in traditional construction it was the nails that provided the fastening strength, now it is the glue. It has become quite common since the 1980s for both carvel and clinker construction to rely almost completely on glue for fastening. Many small boats, especially light plywood skiffs, are built without any mechanical fasteners such as nails and lag screws at all, as the glue is far stronger.

See also

- Clinker (boat building) — by way of contrast, the predominant method of ship construction used in Northern Europe before the carvel.