Articaine

| |

| |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

|

(RS)-Methyl 4-methyl-3-(2-propylaminopropanoylamino)thiophene-2-carboxylate | |

| Clinical data | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Legal status |

|

| Routes of administration | Subcutaneous, submucosal, parenteral, epidural, intravenous |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Liver, plasma |

| Biological half-life | 30 min |

| Excretion | Liver and unspecific plasma estearases[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number |

23964-57-0 |

| ATC code | N01BB08 |

| PubChem | CID 32170 |

| DrugBank |

DB09009 |

| ChemSpider |

29837 |

| UNII |

D3SQ406G9X |

| KEGG |

D07468 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1093 |

| Synonyms | Carticaine |

| Chemical data | |

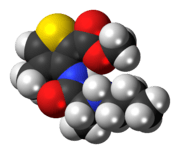

| Formula | C13H20N2O3S |

| Molar mass |

284.37 g/mol 320.836 g/mol (HCl) |

| Chirality | 1 : 1 mixture (racemate) |

| |

| |

| | |

Articaine is a dental amide-type local anesthetic. It is the most widely used local anesthetic in a number of European countries[2] and is available in many countries around the world.

History

This drug was first synthesized by Rusching in 1969,[3] and brought to the market in Germany by Hoechst AG, a life-sciences German company, under the brand name Ultracain. This drug was originally referred to as "carticaine" until 1984.[3]

In 1983 it was brought into the North American market, to Canada, under the name Ultracaine for dental use, manufactured in Germany and distributed by Hoechst-Marion-Roussel. This brand is currently manufactured in Germany by Sanofi-Aventis and distributed in North America by Hansamed Limited (since 1999). After Ultracaine's patent protection expired, new generic versions arrived to the Canadian market: (in order of appearance) Septanest (Septodont), Astracaine, (originally by AstraZeneca and now a Dentsply product), Zorcaine (Carestream Health/Kodak) and Orabloc (Pierrel)

It was approved by the FDA in April 2000, and became available in the United States of America two months later under the brand name Septocaine, an anesthetic/vasoconstrictor combination with Epinephrine 1:100,000 (trade name Septodont). Zorcaine became available there a few years later, also. Articadent (Dentsply) became available in the United States in October 2010. The three brands currently available in the United States are all manufactured for these companies by Novocol Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Canada). Ubistesin and Ubistesin Forte (3M ESPE) are also widely used in the United States and Europe. Orabloc (Pierrel) is aseptically manufactured and was approved by the FDA in 2010, became available in Canada in 2011, and in Europe from 2013.

Articaine is currently available for the North American dental market:

- In Canada:

- As articaine hydrochloride 4% with epinephrine 1:100,000

- Ubistesin Forte

- Ultracaine DSF

- Septanest SP

- Astracaine Forte

- Zorcaine

- Orabloc (articaine hydrochloride 4% and epinephrine 1:100,000)

- As articaine hydrochloride 4% with epinephrine 1:200,000

- Ubistesin

- Ultracaine DS

- Septanest N

- Astracaine

- Orabloc (articaine hydrochloride 4% and epinephrine 1:200,000)

- As articaine hydrochloride 4% with epinephrine 1:100,000

- In the USA:

- As articaine hydrochloride 4% with epinephrine 1:100,000

- Septocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000

- Zorcaine

- Articadent with epinephrine 1:100,000

- Orabloc (articaine hydrochloride 4% and epinephrine 1:100,000)

- As articaine hydrochloride 4% with epinephrine 1:200,000

- Septocaine with epinephrine 1:200,000

- Articadent with epinephrine 1:200,000

- Orabloc (articaine hydrochloride 4% and epinephrine 1:200,000)

- As articaine hydrochloride 4% with epinephrine 1:100,000

An epinephrine-free (adrenaline-free) version is available in Europe under the brand name Ultracain D. However, version with epinephrine (adrenaline) is available in Europe under the brand name Supracain 4% with epinephrine concentration of 1:200,000.

Structure and metabolism

The amide structure of articaine is similar to that of other local anesthetics, but its molecular structure differs through the presence of a thiophene ring instead of a benzene ring. Articaine is exceptional because it contains an additional ester group that is metabolized by esterases in blood and tissue.[2] The elimination of articaine is exponential with a half-life of 20 minutes.[4][5] Since articaine is hydrolized very quickly in the blood, the risk of systemic intoxication seems to be lower than with other anesthetics, especially if repeated injection is performed.[6]

Clinical use

Articaine is used for pain control. Like other local anesthetic drugs, articaine causes a transient and completely reversible state of anesthesia (loss of sensation) during (dental) procedures.[7]

In dentistry, articaine is used mainly for infiltration injections. Articaine, while not proven, has been associated with higher risk of nerve damage when used as a block technique. [8] However, the ability for articaine to penetrate dense cortical bone - as found in the lower jaw (mandible) - more than most other local anaesthetics, negates the need to perform nerve blocks.

In people with hypokalemic sensory overstimulation, lidocaine is not very effective, but articaine works well.[9]

Contraindications

- Patients allergic to amide-type anesthetics

- Patients allergic to metabisulfites (preservative present in the formula to extend the life of the epinephrine). There is no cross-allergenicity between sulfites (preservatives), sulfur, and the "sulfa"-type antibiotics.[10]

- Patients with idiopathic or congenital methemoglobinemia [11]

- Patients with hemoglobinopathies (Sickle Cell Disease) [11]

- Articaine is not contraindicated in patients with sulfa allergies; there is no cross-allergenicity between articaine's sulphur-bearing thiophene ring and sulfonamides.[12]

Methylparaben is no longer present in any dental local anesthetic formula available in North America.[13]

Methemoglobinemia is not a concern in the dental practice, due to the small volumes of articaine used.[13]

Paresthesia controversy

Paresthesia, a short to long-term numbness or altered sensation affecting a nerve, is a well-known complication of injectable local anesthetics and has been present even before articaine was available.[14][15]

An article by Haas and Lennon published in 1993[16] seems to be the original source for the controversy surrounding articaine.

This paper, analyzed 143 cases reported in to the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario (RCDSO) over a 21-year period. The results from their analysis seemed to indicate that 4% local anesthetics had a higher incidence of causing paresthesia, an undesirable temporary or permanent complication, after the injection. The authors concluded that “...the overall incidence of paresthesia following local anesthetic administration for non-surgical procedures in dentistry in Ontario is very low, with only 14 cases being reported out of an estimated 11,000,000 injections in 1993. However if paresthesia does occur, the results of this study are consistent with the suggestion that it is significantly more likely to do so if either articaine or prilocaine is used.”

In another paper by the same authors,[17] 19 reported paresthesia cases in Ontario for 1994 were reviewed, concluding that the incidence of paresthesia was 2.05 per million injections of 4% anesthetic drugs. Another follow up study by Miller and Haas published in 2000,[18] concluded that the incidence of paresthesia from either prilocaine or articaine (the only two 4% drugs in the dental market) was close to 1:500,000 injections. (An average dentists gives around 1,800 injections in a year.[19])

Almost all recorded cases of long term numbness or altered sensation (paresthesia) seem to only be present when this anesthetic is used for dental use (no PubMed references for paresthesia with articaine for other medical specialties), and only affect, in the vast majority of the reports, the lingual nerve.

Nonetheless, direct damage to the nerve caused by 4% drugs has never been scientifically proven.[20]

Some research points to needle trauma as the cause of the paresthesia events.[21][22]

References

- ↑ Oertel R, Ebert U, Rahn R, Kirch W. Clinical pharmacokinetics of articaine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997 Dec;33(6):421

- 1 2 Oertel R, Ebert U, Rahn R, Kirch W. Clinical pharmacokinetics of articaine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997 Dec;33(6):418.

- 1 2 Malamed SF. Handbook of local anaesthesia, p. 71, 5th ed. St. Louis,Mosby; 2004.

- ↑ HornkeI, Eckert HG, Rupp W. Pharnakokinetik und Metabolismus von Articain nach intramuskularer Injektion am mannlichen Probanden. Dtsch Z Mund Kiefer Gesichts Chir 1984; 8:67-71

- ↑ Kirch W, Kitteringham N, Lambers G, et al. Die klinische Pharmakokinetik von Articain nach intraoraler und intramuskularer Application. Schweiz Monatsschr Zahnheilkd 1983; 93: 713-9

- ↑ Oertel R, Ebert U, Rahn R, Kirch W. Clinical pharmacokinetics of articaine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1997 Dec;33(6):420.

- ↑ Malamed SF. Handbook of local anaesthesia, p. 3, 5th ed. St. Louis, Mosby; 2004.

- ↑ Pogrel MA. Permanent nerve damage from inferior alveolar nerve blocks--an update to include articaine. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007 Apr;35(4):271-3.

- ↑ Segal MM, Rogers GF, Needleman HL, Chapman CA (2007). "Hypokalemic sensory overstimulation". J Child Neurol 22 (12): 1408–10. doi:10.1177/0883073807307095. PMID 18174562.

- ↑ Malamed SF. Handbook of local anaesthesia, p. 320, 5th ed. St. Louis, Mosby; 2004.

- 1 2 Malamed SF. Handbook of local anaesthesia, p. 65, 6th ed. St. Louis, Mosby; 2013.

- ↑ Becker, DE; Reed, KL: Essentials of Local Anesthetic Pharmacology. Anesth Prog 53:98-109 2006

- 1 2 Malamed SF. Handbook of local anaesthesia, p. 73, 5th ed. St. Louis, Mosby; 2004.

- ↑ Pogrel MA, Bryan J, Regezi J. Nerve damage associated with inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995 Aug;126(8):1150-5.

- ↑ Pogrel MA, Thamby S. Permanent nerve involvement resulting from inferior alveolar nerve blocks. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000 Jul;131(7):901-7. Erratum in: J Am Dent Assoc 2000 Oct;131(10):1418.

- ↑ Haas DA, Lennon D. A 21 year retrospective study of reports of paraesthesia following local anaesthetic administration. J Can Dent Assoc. 1995 Apr;61(4):319-20, 323-6, 329-30.

- ↑ Haas DA, Lennon D. A review of local anaesthetic-induced paraesthesia in Ontario in 1994. J Dent Res 1996; 75(Special Issue):247.

- ↑ Miller PA, Haas DA. Incidence of local anaesthetic-induced neuropathies in Ontario from 1994–1998. J Dent Res 2000; 79 (Special Issue):627.

- ↑ Haas DA, Lennon D Local anaesthetic use by dentists in Ontario. J Can Dent Assoc. 1995 Apr;61(4):297-304

- ↑ Malamed SF. Local anesthetics: dentistry's most important drugs, clinical update 2006. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2006 Dec;34(12):971-6

- ↑ Pogrel MA, Permanent nerve damage from inferior alveolar nerve blocks—an update to include articaine. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2007 Apr;35(4):271-3

- ↑ Hoffmeister B, Morphological changes of peripheral nerves following intraneural injection of local anaesthetic, Dtsch Zahnarztl Z. 1991 Dec;46(12):828-30

External links

- Carticaine(articaine) PubChem page

- Orabloc

- Septodont

- Structure

- Permanent Nerve Damage from Inferior Alveolar Nerve Blocks: An update to include articaine.

- Permanent nerve involvement resulting from inferior alveolar nerve blocks.

- Nerve damage associated with inferior alveolar nerve blocks.

- Haas DA (2006). "Articaine and paresthesia: epidemiological studies". J Am Coll Dent 73 (3): 5–10. PMID 17477212.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||