Carcassonne

| Carcassonne Carcassona | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Panorama of the Cité de Carcassonne | ||

| ||

Carcassonne | ||

|

Location within Languedoc-Roussillon region  Carcassonne | ||

| Coordinates: 43°13′N 2°21′E / 43.21°N 2.35°ECoordinates: 43°13′N 2°21′E / 43.21°N 2.35°E | ||

| Country | France | |

| Region | Languedoc-Roussillon-Midi-Pyrénées | |

| Department | Aude | |

| Arrondissement | Carcassonne | |

| Intercommunality | Carcassonne | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor (2008–2014) | Jean-Claude Perez (PS) | |

| Area1 | 65.08 km2 (25.13 sq mi) | |

| Population (2008)2 | 47,634 | |

| • Density | 730/km2 (1,900/sq mi) | |

| INSEE/Postal code | 11069 / 11000 | |

| Elevation |

81–250 m (266–820 ft) (avg. 111 m or 364 ft) | |

|

1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km² (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. 2 Population without double counting: residents of multiple communes (e.g., students and military personnel) only counted once. | ||

Carcassonne (French: [kaʁ.ka.sɔn]; Occitan: Carcassona [kaɾkaˈsunɔ]; Latin: Carcaso) is a fortified French town in the Aude department, of which it is the prefecture, in the Region of Languedoc-Roussillon.

Occupied since the Neolithic, Carcassonne is located in the Aude plain between two great axes of circulation linking the Atlantic to the Mediterranean sea and the Massif Central to the Pyrénées. Its strategic importance was quickly recognized by the Romans who occupied its hilltop until the demise of the Western Roman Empire and was later taken over by the Visigoths in the fifth century who founded the city. Also thriving as a trading post due to its location, it saw many rulers who successively built up its fortifications up until its military significance was greatly reduced by the Treaty of the Pyrenees in 1659.

The city is famous for the Cité de Carcassonne, a medieval fortress restored by the theorist and architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc in 1853 and added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in 1997.[1] Consequently, Carcassonne greatly profits from tourism but also counts manufacture and wine-making as some of its other key economic sectors.

History

The first signs of settlement in this region have been dated to about 3500 BC, but the hill site of Carsac – a Celtic place-name that has been retained at other sites in the south – became an important trading place in the 6th century BC. The Volcae Tectosages fortified the oppidum.

The folk etymology – involving a châtelaine named Carcas, a ruse ending a siege and the joyous ringing of bells ("Carcas sona") – though memorialized in a neo-Gothic sculpture of Mme. Carcas on a column near the Narbonne Gate, is of modern invention. The name can be derived as an augmentative of the name Carcas.

Carcassonne became strategically identified when Romans fortified the hilltop around 100 BC and eventually made the colonia of Julia Carsaco, later Carcasum (by the process of swapping consonants known as metathesis). The main part of the lower courses of the northern ramparts dates from Gallo-Roman times. In 462 the Romans officially ceded Septimania to the Visigothic king Theodoric II who had held Carcassonne since 453; he built more fortifications at Carcassonne, which was a frontier post on the northern marches: traces of them still stand. Theodoric is thought to have begun the predecessor of the basilica that is now dedicated to Saint Nazaire. In 508 the Visigoths successfully foiled attacks by the Frankish king Clovis. Saracens from Barcelona took Carcassonne in 725, but King Pepin the Short (Pépin le Bref) drove them away in 759-60; though he took most of the south of France, he was unable to penetrate the impregnable fortress of Carcassonne.

A medieval fiefdom, the county of Carcassonne, controlled the city and its environs. It was often united with the County of Razès. The origins of Carcassonne as a county probably lie in local representatives of the Visigoths, but the first count known by name is Bello of the time of Charlemagne. Bello founded a dynasty, the Bellonids, which would rule many honores in Septimania and Catalonia for three centuries.

In 1067, Carcassonne became the property of Raimond-Bernard Trencavel, viscount of Albi and Nîmes, through his marriage with Ermengard, sister of the last count of Carcassonne. In the following centuries, the Trencavel family allied in succession either with the counts of Barcelona or of Toulouse. They built the Château Comtal and the Basilica of St. Nazaire and St. Celse. In 1096, Pope Urban II blessed the foundation stones of the new cathedral.

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1793 | 10,400 | — |

| 1800 | 15,219 | +46.3% |

| 1806 | 14,985 | −1.5% |

| 1821 | 15,752 | +5.1% |

| 1831 | 20,997 | +33.3% |

| 1836 | 22,623 | +7.7% |

| 1841 | 21,333 | −5.7% |

| 1846 | 21,607 | +1.3% |

| 1851 | 20,005 | −7.4% |

| 1856 | 19,915 | −0.4% |

| 1861 | 20,644 | +3.7% |

| 1866 | 22,173 | +7.4% |

| 1872 | 24,407 | +10.1% |

| 1876 | 25,971 | +6.4% |

| 1881 | 27,512 | +5.9% |

| 1886 | 29,330 | +6.6% |

| 1891 | 28,235 | −3.7% |

| 1896 | 29,298 | +3.8% |

| 1901 | 30,720 | +4.9% |

| 1906 | 30,976 | +0.8% |

| 1911 | 30,689 | −0.9% |

| 1921 | 29,314 | −4.5% |

| 1926 | 33,974 | +15.9% |

| 1931 | 34,921 | +2.8% |

| 1936 | 33,441 | −4.2% |

| 1946 | 38,139 | +14.0% |

| 1954 | 37,035 | −2.9% |

| 1962 | 40,897 | +10.4% |

| 1968 | 43,616 | +6.6% |

| 1975 | 42,154 | −3.4% |

| 1982 | 41,153 | −2.4% |

| 1990 | 43,470 | +5.6% |

| 1999 | 43,950 | +1.1% |

| 2008 | 47,634 | +8.4% |

Carcassonne became famous in its role in the Albigensian Crusades, when the city was a stronghold of Occitan Cathars. In August 1209 the crusading army of the Papal Legate, Abbot Arnaud Amalric, forced its citizens to surrender. Raymond-Roger de Trencavel was imprisoned whilst negotiating his city's surrender, and died in mysterious circumstances three months later in his own dungeon. Simon De Montfort was appointed the new viscount. He added to the fortifications.

In 1240, Trencavel's son tried to reconquer his old domain but in vain. The city submitted to the rule of the kingdom of France in 1247. Carcassonne became a border fortress between France and the Crown of Aragon under the Treaty of Corbeil (1258). King Louis IX founded the new part of the town across the river. He and his successor Philip III built the outer ramparts. Contemporary opinion still considered the fortress impregnable. During the Hundred Years' War, Edward the Black Prince failed to take the city in 1355, although his troops destroyed the Lower Town.

._Ch%C3%A2teau_comtal_de_la_cit%C3%A9)_-_Fonds_Trutat_-_51Fi477.jpg)

In 1659, the Treaty of the Pyrenees transferred the border province of Roussillon to France, and Carcassonne's military significance was reduced. Fortifications were abandoned, and the city became mainly an economic centre that concentrated on the woollen textile industry, for which a 1723 source quoted by Fernand Braudel found it "the manufacturing centre of Languedoc".[2] It remained so until the Ottoman market collapsed at the end of the eighteenth century, thereafter reverting to a country town.[3]

Historical importance

Carcassonne was the first fortress to use hoardings in times of siege. Temporary wooden ramparts would be fitted to the upper walls of the fortress through square holes beneath the rampart itself. It provided protection to defenders on the wall and allowed defenders to go out past the wall to drop projectiles on attackers at the wall beneath.

Main sights

The fortified city

The fortified city itself consists essentially of a concentric design of two outer walls with 53 towers and barbicans to prevent attack by siege engines. The castle itself possesses its own drawbridge and ditch leading to a central keep. The walls consist of towers built over quite a long period.[4] One section is Roman and is notably different from the medieval walls with the tell-tale red brick layers and the shallow pitch terracotta tile roofs. One of these towers housed the Catholic Inquisition in the 13th Century and is still known as "The Inquisition Tower".

Carcassonne was struck off the roster of official fortifications under Napoleon and the Restoration, and the fortified cité of Carcassonne fell into such disrepair that the French government decided that it should be demolished. A decree to that effect that was made official in 1849 caused an uproar. The antiquary and mayor of Carcassonne, Jean-Pierre Cros-Mayrevieille, and the writer Prosper Mérimée, the first inspector of ancient monuments, led a campaign to preserve the fortress as a historical monument. Later in the year the architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, already at work restoring the Basilica of Saint-Nazaire, was commissioned to renovate the place.

In 1853, works began with the west and southwest walling, followed by the towers of the porte Narbonnaise and the principal entrance to the cité. The fortifications were consolidated here and there, but the chief attention was paid to restoring the roofing of the towers and the ramparts, where Viollet-le-Duc ordered the destruction of structures that had encroached against the walls, some of them of considerable age. Viollet-le-Duc left copious notes and drawings on his death in 1879, when his pupil Paul Boeswillwald, and later the architect Nodet continued the rehabilitation of Carcassonne.

The restoration was strongly criticized during Viollet-le-Duc's lifetime. Fresh from work in the north of France, he made the error of using slates and restoring the roofs as point-free environment. Yet, overall, Viollet-le-Duc's achievement at Carcassonne is agreed to be a work of genius, though not of the strictest authenticity.

Other

Another bridge, Pont Marengo, crosses the Canal du Midi and provides access to the railway station. Lac de la Cavayère has been created as a recreational lake and is about five minutes from the city centre.

Further sights include:

- the Basilica of St. Nazaire and St. Celse

- Carcassonne Cathedral

- Church of St. Vincent

Climate

| Climate data for Carcassonne (1981–2010 averages) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 21.1 (70) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.3 (81.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

35.2 (95.4) |

39.8 (103.6) |

40.2 (104.4) |

41.9 (107.4) |

36.4 (97.5) |

31.0 (87.8) |

26.2 (79.2) |

22.4 (72.3) |

41.9 (107.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.7 (49.5) |

11.1 (52) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.0 (62.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

18.6 (65.5) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.1 (37.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

7.7 (45.9) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.2 (63) |

17.0 (62.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.2 (52.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

9.7 (49.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.5 (9.5) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.4 (47.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 69.3 (2.728) |

54.1 (2.13) |

54.3 (2.138) |

73.1 (2.878) |

56.7 (2.232) |

45.9 (1.807) |

28.5 (1.122) |

42.6 (1.677) |

42.5 (1.673) |

59.5 (2.343) |

59.5 (2.343) |

62.5 (2.461) |

648.5 (25.531) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.4 | 7.9 | 8.0 | 9.5 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 7.8 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 87.5 |

| Average snowy days | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 1.4 | 7.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82 | 79 | 74 | 74 | 72 | 69 | 64 | 68 | 73 | 80 | 82 | 84 | 75.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 97.2 | 119.6 | 172.6 | 188.1 | 214.7 | 239.7 | 275.4 | 260.4 | 212.9 | 144.6 | 102.5 | 91.6 | 2,119.3 |

| Source #1: Météo France[5][6] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Infoclimat.fr (humidity and snowy days, 1961–1990)[7] | |||||||||||||

Economy

The newer part (Ville Basse) of the city on the other side of the Aude river (which dates back from the Middle Ages, created after the crusade) manufactures shoes, rubber and textiles. It is also the centre of a major AOC wine-growing region. A major part of its income, however, comes from the tourism connected to the fortifications (Cité) and from boat cruising on the Canal du Midi. Carcassonne is also home to the MKE Performing Arts Academy. Carcassonne receives about three million visitors annually.

Transport

In the late 1990s Carcassonne airport started taking budget flights to and from European airports and by 2009 had regular flight connections with Porto, Bournemouth, Cork, Dublin, Frankfurt-Hahn, London-Stansted, Liverpool,[8] East Midlands, Glasgow-Prestwick and Charleroi.

The Gare de Carcassonne railway station offers direct connections to Toulouse, Narbonne, Perpignan, Paris, Marseille and several regional destinations. The A61 motorway connects Carcassonne with Toulouse and Narbonne.

Education

Language

Historically, the language spoken in Carcassonne and throughout Languedoc-Roussillon was not French but Occitan.

Sport

Carcassonne was the starting point for a stage in the 2004 Tour de France and a stage finish in the 2006 Tour de France.

As in the rest of the southwest of France, rugby union is popular in Carcassonne. The city is represented by Union Sportive Carcassonnaise, known locally simply as USC. The club have a proud history, having played in the French Championship Final in 1925, and currently compete in Pro D2, the second tier of French rugby.

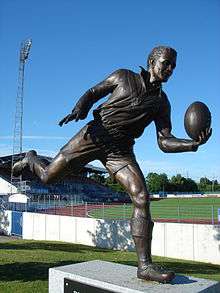

Rugby league is also played, by the AS Carcassonne club. They are involved in the Elite One Championship. Puig Aubert is the most notable rugby league player to come from the Carcassonne club. There is a bronze statue of him outside the Stade Albert Domec at which the city's teams in both codes play.

In culture

- The French poet Gustave Nadaud made Carcassonne famous as a city a man dreamed of seeing but could not see before he died. His poem inspired many others and was translated into English several times.[9] Georges Brassens has sung a musical version of the poem. Lord Dunsany wrote a short story "Carcassonne" (in A Dreamer's Tales) as did William Faulkner.

- On 6 March 2000 France issued a stamp commemorating the fortress of Carcassonne.[10]

- The history of Carcassonne is re-told in the novels Labyrinth, Sepulchre and Citadel by Kate Mosse.

- A board game and a video game version of it are named after this town.

- Portions of the 1991 film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves were shot in and around Carcassonne.

- A 1993 album by Stephan Eicher was named Carcassonne.

- In the one-man show Sea Wall, starring Andrew Scott, Carcassonne is mentioned frequently as a setting.

Personalities

- Paul Lacombe, composer, 1837

- Théophile Barrau, sculptor, 1848

- Paul Sabatier, co-recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1854

- Gilbert Benausse, rugby league footballer, 1932

- Michael Martchenko, illustrator, 1942

- Maurice Sarrail, General of Division during the First World War, 1856

- David Ferriol, rugby league player, 1979

- Olivia Ruiz, pop singer, 1980

- Fabrice Estebanez, rugby union player, 1981

- Henry d'Estienne, Painter

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Carcassonne is twinned with:

Eggenfelden, Germany

Eggenfelden, Germany Baeza, Spain

Baeza, Spain Hargesheim, Germany[11]

Hargesheim, Germany[11]

References

- ↑ "Historic Fortified City of Carcassonne". UNESCO. Accessed 13 February 2014.

- ↑ Fernand Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce 1982, vol. II of Civilization and Capitalism, Brian Anderson.

- ↑ Faroqhi, Suraiya N. (2006). "Introduction". In Suraiya N. Faroqhi, ed., The Cambridge History of Turkey, Volume 3: The Later Ottoman Empire, 1603–1839, pp. 3–17. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62095-6. See p. 4.

- ↑ midi-france.info. "Historic Cities: Caracassonne". midi-france.info.

- ↑ "Données climatiques de la station de Carcassonne" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Climat Languedoc-Roussillon" (in French). Meteo France. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Normes et records 1961-1990: Carcassonne-Salvaza (11) - altitude 126m" (in French). Infoclimat. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ↑ Liverpool - Carcassonne

- ↑ Clark, Francis E. (1922). Memories of Many Men in Many Lands. The Plimpton Press. p. 504. Retrieved 2013-03-08.

- ↑ Musée de La Poste

- ↑ La Dépêche Du Midi. "Carcassonne se trouve une jumelle" (in French). Retrieved 26 June 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carcassonne. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Carcassonne. |

- Virtual tour of the fortified walls of the city of Carcasonne

- Official website of the city of Carcassonne (English) / (French) / (Spanish) / (German) / (Dutch)

- Cité de Carcassonne, from the French Ministry of Culture

- INSEE

| ||||||

|