Pedestrian zone

.jpg)

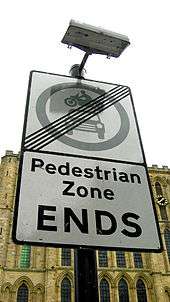

Pedestrian zones (also known as auto-free zones and car-free zones, and as pedestrian precincts in British English[1]) are areas of a city or town reserved for pedestrian-only use and in which some or all automobile traffic may be prohibited. They are instituted by communities who feel that it is desirable to have pedestrian-only areas. Converting a street or an area to pedestrian-only use is called pedestrianisation.

Pedestrian zones have a great variety of attitudes or rules towards human-powered vehicles such as bicycles, inline skates, skateboards and kick scooters. Some have a total ban on anything with wheels, others ban certain categories, others segregate the human-powered wheels from foot traffic, and others still have no rules at all. Many of Middle Eastern casbas have no wheeled traffic, but use donkey-driven or hand-driven carts for freight transport.

Europe

The term "pedestrianised zone" is used in British English, and most other European countries use a similar term (French: zone piétonne, German: Fußgängerzone, Spanish: zona peatonal, Italian: area pedonale, Dutch: voetgangerszone).

The first purpose-built pedestrian street in Europe is the Lijnbaan in Rotterdam, opened in 1953. The first pedestrianised shopping centre in the United Kingdom was in Stevenage in 1959.

A large number of European towns and cities have made part of their centres car-free since the early 1960s. These are often accompanied by car parks on the edge of the pedestrianised zone, and, in the larger cases, park and ride schemes. Central Copenhagen is one of the largest and oldest: It was converted from car traffic into pedestrian zone in 1962 on November 17 as an experiment and is centered on Strøget, a pedestrian shopping street, which is in fact not a single street but a series of interconnected avenues which create a very large pedestrian zone, although it is crossed in places by streets with vehicular traffic. Most of these zones allow delivery trucks to service the businesses located there during the early morning, and street-cleaning vehicles will usually go through these streets after most shops have closed for the night.

Car free towns, cities and regions

There are many towns and cities in Europe which have never allowed motor vehicles. The archetypal examples include Venice, which occupies myriad islands in a lagoon, divided by and accessed from canals and Zermatt in the Swiss Alps, which has been car-free for more than three decades. Motor traffic stops at the car park at the head of the viaduct from the mainland, and water transport or walking takes over from there. However, motor vehicles are allowed on the Lido. Other examples are Cinque Terre in Italy, Ghent in Belgium, which is one of the largest car-free areas in Europe and the Old Town of Rhodes, since many, if not most of the streets are too steep and/or narrow for automobile circulation. Mount Athos, an Autonomous Monastic State within the sovereignty of Greece, does not permit automobiles on its territory. Trucks and work-related vehicles only are in use there. The medieval city of Mdina in Malta does not allow automobiles past the city walls. It is known as the "Silent City" because of the absence of motor traffic in the city. Sark, an island in the English Channel is a car-free zone where only bicycles, carriages and tractors are used as transportation.

In order to facilitate transport from the car parkings in car-free cities (located at the edge of the towns), the implementation of bus stations, bicycle sharing stations, and the like near these car parkings increase transportation options.

Carfree development in Europe

Definitions and types

The above section describes places which are mainly carfree for historical reasons. The term carfree development implies a physical change - either new building or changes to an existing built area.

Melia et al. (2010)[2] define carfree development as follows:

Carfree developments are residential or mixed use developments which:

- Normally provide a traffic free immediate environment, and:

- Offer no parking or limited parking separated from the residence, and:

- Are designed to enable residents to live without owning a car.

This definition (which they distinguish from the more common 'low car development') is based mainly on experience in Northwestern Europe, where the movement for carfree development began. Within this definition, three types are identified:

- Vauban model

- Limited Access model

- Pedestrianised centres with residential population

Vauban

Vauban is according to this definition, the largest carfree development in Europe, with over 5,000 residents. Whether it can be considered carfree is open to debate: many local people prefer the term 'stellplatzfrei' - literally 'free from parking spaces' to describe the traffic management system there. Vehicles are allowed down the residential streets at walking pace to pick up and deliver, but not to park, although there are frequent infractions. Residents of the stellplatzfrei 'areas must sign an annual declaration stating whether they own a car or not. Car owners must purchase a place in one of the multi-storey car parks on the periphery, run by a council-owned company. The cost of these spaces – € 17,500 in 2006, plus a monthly fee – acts as a disincentive to car ownership.

Limited Access type

The more common form of carfree development involves some sort of physical barrier, which prevents motor vehicles from penetrating into a carfree interior. Melia et al.[2] describe this as the 'Limited Access' type. In some cases, such as Stellwerk 60 in Cologne, there is a removable barrier, controlled by a residents' organisations. In others such as Waterwijk (Amsterdam) (article in Dutch) vehicular access is only available from the exterior.

Pedestrianised centres

Whereas the first two models apply to newly built carfree developments, most pedestrianised city, town and district centres have been retro-fitted. Pedestrianised centres may be considered carfree developments where they include a significant number of residents, mostly without cars, due to new residential development within them, or because they already included dwellings when they were pedestrianised. The largest example in Europe is Groningen with a city centre population of 16,500.[3]

Characteristics and benefits of carfree developments

Several studies have been done on European carfree developments. The most comprehensive was conducted in 2000 by Jan Scheurer.[4] Other more recent studies have been made of specific carfree areas such as Vienna's Floridsdorf carfree development.[5]

Characteristics of carfree developments:

- very low levels of car use, resulting in much less traffic on surrounding roads.

- high rates of walking and cycling.

- more independent movement and active play amongst children.

- less land taken for parking and roads - more available for green or social space.

The main benefits found for carfree developments:

- Low atmospheric emissions.

- Low road accident rates.

- Better built environment conditions.

- Discouragement of private car and other motorized vehicles (measure of travel demand management).

- Encouragement of active modes.

The main problems related to parking management. Where parking is not controlled in the surrounding area, this often results in complaints from neighbours about overspill parking.

North America

In North America, where a more commonly used term is pedestrian mall, such areas are still in their infancy. Few cities have pedestrian zones, but some have pedestrianized single streets. Some cities have transit malls. Many pedestrian streets are surfaced with cobblestones, or pavement bricks, thus discouraging any kind of wheeled traffic, including wheelchairs. They are rarely completely free of motor vehicles. Often, all of the cross streets are open to motorized traffic, which thus intrudes on the pedestrian flow at every street corner. In a few pedestrian streets with no cross street cars or trucks, deliveries are made by trucks by night.

Canada

Some Canadian examples are the Sparks Street Mall area of Ottawa, the Distillery District in Toronto, Scarth Street Mall in Regina, Stephen Avenue Mall in Calgary (with certain areas open to parking for permit holders) and part of Prince Arthur street and the Gay Village in Montreal. Algonquin and Ward's Islands, parts of the Toronto Islands group, are also car-free zones for all 700 residents. Since the summer of 2004, Toronto has also been experimenting with "Pedestrian Sundays" in its busy Kensington Market. Granville Mall in Halifax, Nova Scotia was a run-down section of buildings on Granville Street built in the 1840s that was restored in the late 1970s. The area was then closed off to vehicles.

United States

In the United States, these zones are commonly called pedestrian malls or pedestrian streets. Pedestrian zones are rare in the United States, although some cities have created single pedestrian streets.

Mackinac Island, between the upper and lower peninsulas of Michigan, banned horseless carriages in 1896, making it auto-free. The original ban still stands, except for emergency vehicles.[6] Travel on the island is largely by foot, bicycle, or horse-drawn carriage. An 8-mile (13 km) road, M-185 rings the island, and numerous roads cover the interior. M-185 is the only highway in the United States without motorized vehicles.

Downtown Crossing in Boston is a shopping district which prohibits automobiles during daytime hours. Both the main thoroughfare of Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, and Memorial Drive, a busy road in Cambridge, MA are closed to car traffic each Sunday during the summer to allow pedestrians, bikers, skateboarders and roller/inlineskaters an opportunity to use the road.

A number of streets and malls in New York City are now pedestrian-only, including 6 1/2 Avenue, Fulton Street, parts of Broadway, and a block of 25th Street. [7]

Fire Island in Suffolk County, New York is pedestrianised east of the Fire Island Lighthouse and west of Smith Point County Park (with the exception of emergency vehicles).

Supai, Arizona, located within the Havasupai Indian Reservation is entirely car-free, the only community in the United States where mail is still carried out by mule. Supai is located eight miles from the nearest road, and is accessible only by foot, horse/mule, or helicopter.

State Street in Madison, Wisconsin is the largest pedestrian mall in Wisconsin and connects the University of Wisconsin to Capitol Square in Downtown Madison. The street houses some of Madison's oldest buildings and stores, as well as theaters such as the Orpheum and the Overture Center for the Arts.

A portion of Third Street in Santa Monica, California was converted into a pedestrian mall in the 1960s to become what is now the Third Street Promenade, a very popular shopping district located just a few blocks from the beach and Santa Monica Pier.

Mexico

Playa del Carmen has a pedestrian mall the 5 ave. that stretches 4 km.and receives 4 million visitors annually with hundreds of shops and restaurants

South America

Argentina

Argentina's big cities; Córdoba, Mendoza and Rosario have lively pedestrianised street centers (Spanish: peatonales) combined with town squares and parks which are crowded with people walking at every hour of the day and night. Most (if not all) of Argentina's cities are human-scale and pedestrian-friendly, although vehicle traffic may be hectic in some areas.

In Buenos Aires, some stretches of Calle Florida have been pedestrianised since 1913,[8] which makes it one of the oldest car-free thoroughfares in the world today. Pedestrianised Florida, Lavalle and other streets contribute to a vibrant shopping and restaurant scene where street performers and tango dancers abound, streets are crossed with vehicular traffic at chamfered corners.

Brazil

Paquetá Island in Rio de Janeiro is auto-free. The only cars allowed on the island are police and ambulance vehicles. In Rio de Janeiro, the roads beside the beaches are auto-free on Sundays and holidays.

Downtown Rio de Janeiro, Ouvidor Street, over almost its entire length, has been continually a pedestrian space since the mid-nineteenth century when not even carts or carriages were allowed. And the Saara District, also downtown, consists of some dozen or more blocks of colonial streets, off limits to cars, and crowded with daytime shoppers. Likewise, many of the city's hillside favelas are effectively pedestrian zones as the streets are too narrow and/or steep for automobiles.

Eixo Rodoviário, in Brasília, which is 13 kilometer long and 30 meters wide and is an arterial road connecting the center of that city from both southward and northward wings of Brasília's Plano Piloto, perpendicular to the well known Eixo Monumental (Monumental Axis in English), is auto-free on Sundays and holidays.

Rua XV de Novembro (15th of November Street) in Curitiba is one of the first major pedestrian streets in Brazil.

Chile

Chile has many large pedestrian streets. An example is Paseo Ahumada in Santiago and Calle Valparaíso in Viña del Mar.

Colombia

During his 1998-2001 term, the former Bogotá mayor, U.S.-born Enrique Peñalosa, created several pedestrian streets, plazas and bike paths integrated with a new bus rapid transit system.

The historic center of Cartagena closes some streets to cars during certain hours.

Asia

Vehicles have been banned in the town of Matheran, in Maharashtra, India since the time it was discovered in 1854.[9]

In Hong Kong, since 2000, the government has been implementing full-time or part-time pedestrian streets in a number of areas, including Causeway Bay, Central, Wan Chai, Mong Kok, and Tsim Sha Tsui.[10] The most popular pedestrian street is Sai Yeung Choi Street. It was converted into a pedestrian street in 2003. From December 2008 to May 2009, there were three acid attacks during which corrosive liquids were placed in plastic bottles and thrown from the roof of apartments down onto the street.

Pedestrian zones in Japan are called hokōsha tengoku (歩行者天国, literally "pedestrian heaven"). Clis Road, in Sendai, Japan, is a covered pedestrian mall. Several major streets in Tokyo are closed to vehicles during weekends. One particular temporary hokōsha tengoku in Akihabara was cancelled after the Akihabara massacre in which a man rammed a truck into the pedestrian traffic and subsequently stabbed more than 12 people.

Nanjing Road in Shanghai is perhaps the most well-known pedestrian zone in mainland China. Wangfujing is a famous tourist and retail oriented pedestrian zone in Beijing. Chunxilu in Chengdu is the most well known in western China. Dongmen is the busiest business zone in Shenzhen.

Insadong in Seoul, South Korea has a large pedestrian zone (Insadong-gil) during certain hours.

Also in South Korea, in 2013, in the Haenggun-dong neighbourhood of Suwon, streets were closed to cars as a month-long car-free experiment while the city hosted the EcoMobility World Festival. Instead of cars, residents used non-motorized vehicles provided by the festival organizers.[11] The experiment was not unopposed; however, on balance it was considered a success. Following the festival, the city embarked on discussions about adopting the practice on a permanent basis.[12]

In India, a citizens’ initiative in Goa state, has made 18th June Road, Panjim’s main shopping boulevard a Non-Motorised Zone [13](NoMoZo). The road is converted into a NoMoZo for half a day on one Sunday every month.

In Pune, Maharashtra, similar efforts have been made to convert M.G. Road (a.k.a. Main Street) into an open-air mall. The project in questioned aimed to create a so-called "Walking Plaza".[14]

Africa

North Africa contains some of the largest auto-free areas in the world. Fes-al-Bali, a medina of Fes, Morocco, with its population of 156,000, may be the world's largest contiguous completely carfree area, and the medinas of Cairo, Casablanca, Meknes, Essaouira, and Tangier are quite extensive.

Australia

In Australia, as in the US, these zones are commonly called pedestrian malls and in most cases comprise only one street. Most pedestrian streets were created in the late 1970s and 1980s, the first being City Walk, Garema Place in Canberra in 1971. Of 58 pedestrian streets created in Australia in the last quarter of the 20th century, 48 remain today, ten having re-introduced car access between 1990 and 2004.[15] All capital cities in Australia have at least one pedestrian street of which most central are: Pitt Street Mall and Martin Place in Sydney, Bourke Street Mall in Melbourne, Queen Street Mall and Brunswick Street Mall in Brisbane, Rundle Mall in Adelaide, Hay Street and Murray Street Malls in Perth, Elizabeth Street Mall in Hobart, City Walk in Canberra, and Smith Street in Darwin. Many other mid-sized and regional Australian cities also feature pedestrian malls, examples include Langtree Avenue Mildura, Cavill Avenue Gold Coast, Bridge Street Ballarat, Nicholas Street Ipswich, Hargreaves Street Bendigo, Maude Street Shepparton and Little Mallop Street Geelong.

Empircial studies by Jan Gehl indicate an increase of pedestrian traffic as result of public domain improvements in the centres of Melbourne with 39% increase between 1994-2004[16] and Perth with 13% increase between 1993-2009.[17]

Most intensive pedestrian traffic flows on a summer weekday have been recorded in Bourke Street Mall Melbourne with 81,000 pedestrians (2004),[16] Rundle Mall Adelaide with 61,360 pedestrians (2002), Pitt Street Mall Sydney with 58,140 (2007) and Murray Street Mall Perth with 48,350 pedestrians (2009).[17]

The island of Rottnest off Perth is a car free island, only allowing vehicles for essential services. The main form of transport on the island is bicycles, which can be hired or be taken on the ferry.

In Melbourne's north-eastern suburbs, there have been many proposals to make the Doncaster Hill development area a pedestrian zone. If the proposals are passed, the zone could be one of the largest in the world, by area.

Neighbourhoods

Several dozen new carfree neighbourhoods have been built in recent decades, mostly in Europe. An example is Vauban, a neighbourhood of 5,000 in Freiburg, Germany.

Problems caused by pedestrianisation

There were calls for traffic to be reinstated in Trafalgar Square, London, after pedestrianisation caused noise nuisance for visitors to the National Gallery. The director of the gallery is reported to have blamed pedestrianisation for the "trashing of a civic space".[18]

Local shop-keepers may be critical of the effect of pedestrianisation on the viability of their businesses. Reduced through traffic can lead to fewer customers using local businesses.[19]

Pedestrianisation also attracts pickpockets.

See also

- Car Free Days

- Car-free movement

- Footpath

- List of car-free places

- Carfree city

- Living street

- Jan Gehl

- Principles of Intelligent Urbanism

- Bicycle City

References

Notes

- ↑ "pedestrian precinct" entry in Collins Dictionary

- 1 2 Melia, S., Barton, H. and Parkhurst, G. (2010) Carfree, Low Car - What's the Difference? World Transport Policy & Practice 16 (2), 24-32.

- ↑ Gemeente Groningen, (2008) Statistisch Jaarboek.]

- ↑ Scheurer, J. (2001) Urban Ecology, Innovations in Housing Policy and the Future of Cities: Towards Sustainability in Neighbourhood CommunitiesThesis (PhD), Murdoch University Institute of Sustainable Transport.

- ↑ Ornetzeder, M., Hertwich, E.G., Hubacek, K., Korytarova, K. and Haas, W. (2008) The environmental effect of car-free housing: A case in Vienna. Ecological Economics 65 (3), 516-530.

- ↑ Mackinac Island Tourism Bureau website Archived March 5, 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Public Plazas

- ↑ (Spanish) Calle Florida History: www.buenosaires.com

- ↑ Dey, J (19 May 1999). "MMRDA questions council's new designs on Matheran". Mumbai: The Indian Express. Express News. Retrieved Aug 12, 2014.

- ↑ Hong Kong Transport Department Website

- ↑ Strother, Jason (30 September 2013). "Locals applaud car-free month in Korean city". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ "Report presents legacy of car-free neighborhood". EcoMobility world Festival 2013. ICLEI. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ Down To Earth: Walk this way

- ↑ Walking Plaza: The Times of India

- ↑ IRIS: Australian Outdoor Pedestrian Mall Survey 2006 , retrieved 2009-10-02

- 1 2 Melbourne 'Places for People'

- 1 2 City of Perth - Public Spaces Public Life

- ↑ "Trafalgar Square is being trashed, says gallery chief". London Evening Standard (ES London). 2009-07-10. Retrieved 2010-05-17.

- ↑ "‘They’re going to ruin us with the pedestrianisation’". WalesOnline (Media Wales). 2010-04-29. Retrieved 2010-05-17.