Waterloo Campaign: Waterloo to Paris (18–24 June)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

After the their defeat at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815, the French Army of the North, under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte retreated in disarray back towards France. As agreed by the two Seventh Coalition commanders in chief, the Duke of Wellington, commander of the Anglo-allied army, and Prince Blücher, commander of the Prussian army, the French were to be closely pursued by units of the Prussian army.

During the following week, although the remnants of the main French army were joined by the undefeated right wing of the Army of the North, the French were not given time to reorganise by the Coalition generals and they steadily retreated towards Paris.

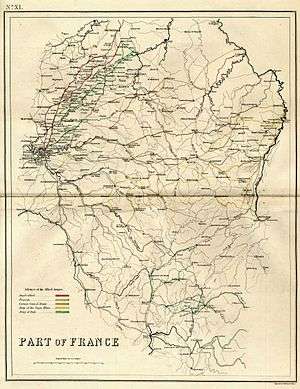

By the end Saturday 24 June (the end of the first week after the defeat at Waterloo) the French who had fought at Waterloo were at Laon under the command of Marshal Soult, while those of the right wing who had fought at the simultaneous Battle of Wavre, under the command of Marshal Grouchy, were at Rethel. The Prussians were in and around Aisonville-et-Bernoville with Blücher's headquarter were at Hannapes, and the Anglo-allies were in the vicinity of Cambrai, Englefontaine, and Le Cateau-Cambrésis which is where Wellington had his headquarters.

The next week (25 June – 1 July) would see the French reach Paris with the Coalition forces about a days march behind them. In the final week of the campaign (2–7 July) the French surrendered, Coalition forces entered Paris and on 8 July Louis XVIII was restored to the throne.

Night 18 June

The 4,000 Prussian cavalry, that kept up an energetic pursuit during the night, under the guidance of the indefatigable Marshal Gneisenau, helped to render the victory at Waterloo still more complete and decisive; and effectually deprived the French of every opportunity of recovering on the Belgian side of the frontier and to abandon most of their cannons.[1][2]

After the Battle of Ligny the French had given little quarter as they as the harried the stranglers of the Prussian army and the Prussians now returned like with like and showed little mercy.[3] Gneisenau later wrote that "it was the finest night of my life". He used mounted drummers to fool the French into thinking that Prussian infantry was close behind his cavalry, which helped to spread panic and make it more difficult for French officers to rally their men.[1][4]

On the main French retreat Genappe was a possible defensive position for a rearguard to delay an enemy, as there was a defile and only one bridge over the river Dyle (Anglo-allied cavalry under the command of Lord Uxbridge had used this feature to help delay the French cavalry the previous day (17 June), as Wellington withdrew his army from Quatre Bras to the Mont-Saint-Jean escarpment [5]). It was here that Marshal Lobau collected three hundred men together and tried to make a stand. However the Prussians quickly dispersed his men and captured him.[6] A Prussian officer reported that

in the town of Genappe alone, six miles from the field of battle, eight hundred [Frenchmen] lay dead, who had suffered themselves to be cut down like cattle.[3]

The cavalry of the Brunswick contingent in the army command of Wellington had been engaged both at Quatre Bras and Waterloo, but they sought and were given permission to join in the pursuit. They eagerly headed the chase and slew all they came across. Incident was recorded in contemporary British accounts as indicative of the Brunswickers' attitude while heading the pursuit. General Duhesme (commander of the Young Guard) who was then commanding the French rearguard was standing by the gate of an inn in Genappe when a Black Brunswicker Hussar seeing that he was a general officer rode up to him. Duhesme requested quarter, the hussar declined and cut him down with his sabre commenting as he slew him "The Duke [of Brunswick] fell the day before yesterday and thou also shalt bite the dust".[3][7][8] This account of the death of Duhesme was also propagated on the histories based on Napoleon's account of the affair, but it was refuted by a relative of Duhesme and his aide-de-camp on the day who said he was mortally wounded at Waterloo and captured in Genappe where he was cared for by Prussian surgeons until he died during the night of 19/20 June.[9][10]

It is difficult to discover, in the whole history of the wars of modern times, an instance in which so fine, so splendid, an army as that of Napoleon, one composed almost exclusively of veterans, all men of one nation, entirely devoted to their chief, and most enthusiastic in his cause, became so suddenly panic stricken, so completely disorganised, and so thoroughly scattered, as was the French army when it lost the Battle of Waterloo.[11]

A defeated army usually covers its retreat by a rearguard, but here there was nothing of the kind: and hence that Army of the North cannot be said to have retreated; but truly to have fled, from the field of Waterloo. No concerted attempt to rally was made on the Belgian soil, and it was not until some of the scattered fragments of the immense wreck had been borne across the French frontier that their partial junction on different points indicated the revival of at least some portion of that mighty mass of warriors; who, but three days before, had marched across this same frontier in all the pride of strength, and in all the assurance of victory.[11]

The rearmost of the fugitives having reached the river Sambre, at Charleroi, Marchienne-au-Pont, and Châtelet, by daybreak of 19 June 1815, indulged themselves with the hope that they might then enjoy a short rest from the fatigues which the relentless pursuit by the Prussians had entailed upon them during the night; but their fancied security was quickly disturbed by the appearance of a few Prussian cavalry, judiciously thrown forward towards the Sambre from the vanguard at Gosselies. They resumed their flight, taking the direction of Beaumont and Philippeville.[12]

19 June

Napoleon

"ABIIT . EXCESSIT . EVASIT . ERUPIT." ("He has left, absconded, escaped and disappeared") — originally to describe the actions of Catiline — was inscribed over the centre of the archway of the Charleroi gate and the military historian William Siborne thought it a fitting epitaph for Napoleon's flight.[13]

An hours rest was all that the harassing pursuit by the Prussians permitted Napoleon to enjoy at Charleroi; and he was compelled to flee across the river Sambre, without the slightest chance of being able to check that pursuit on the Belgian side of the frontier.[14]

From Charleroi, Napoleon proceeded to Philippeville; whence he hoped to be able to communicate more readily with Marshal Grouchy (who was commanding the detached and still intact right wing of the Army of the North). He tarried for four hours expediting orders to generals Rapp, Lecourbe, and Lamarque, to advance with their respective corps by forced marches to Paris (for their corps locations see the military mobilisation during the Hundred Days): and also to the commandants of fortresses, to defend themselves to the last extremity. He desired Marshal Soult to collect together all the troops that might arrive at this point, and conduct them to Laon; for which place he himself started with post horses, at 14:00.[13]

Grouchy and the right wing of the Army of the North

On the morning of 19 June Grouchy continued to engage Thielmann in the Battle of Wavre. It was not until about 11:00 that Grouchy was informed that the army under Napoleon, having been decisively defeated and completely scattered on the preceding evening, was flying across the frontier in the wildest confusion.[15]

On receiving this intelligence, Grouchy's first idea was to march against the rear of the main body of the Prussian army; but, calculating that his force was not adequate for such an enterprise, that the victorious allies might detach a force to intercept his retreat, and that he should be closely followed by the Prussian III Corps (Thielmann's) which he had just defeated; he decided on retiring to Namur, where he could decide his further operations according to further intelligence he could gather as to the current state of affairs.[15]

Prussians

On the morning of 19 June, the cavalry, belonging to the I Corps (Zieten's, IV Corps (Bülow's), and partly to the II Corps Pirch I's, pursuing the disorganised remnants of Napoleon's army, reached the vicinity of Frasnes and Mellet.[16]

The Prussian IV Corps marched at daybreak from Genappe, where it collected together the brigades which had been so much broken up by the continued pursuit. The 8th Prussian Hussars, under Major Colomb, were detached from this corps towards Wavre, to observe Marshal Grouchy. They were supported by the 1st Pomeranian Landwehr Cavalry; and, shortly afterwards, the 2nd Silesiau Landwehr Cavalry, under Lieutenant Colonel Schill, also followed in the same direction.[16]

After some hours rest, the IV Corps marched to Fontaine l'Eveque, where it bivouacked. It had received orders to communicate from this place with Mons. The vanguard, under General Sydow (commander of the 3rd Brigade),[lower-alpha 1] was pushed forward, as far as Leernes,[lower-alpha 2] on the road to Thuin; it being intended that this corps should proceed by the road to Maubeuge, along the river Sambre.[16]

The I Corps (Zieten's), which had from the beginning followed the IV as a reserve, now advanced in pursuit of the French by the direct road to Charleroi. The light cavalry at the head of the column reached the passages of the Sambre at Châtelet, Charleroi, and Marchienne-au-Pont, without meeting any sort of opposition or impediment; nor did it perceive any thing of the French on the other side of the river. The Corps halted for the night at Charleroi: having its vanguard at Mont-sur-Marchienne, and its outposts occupying the line from Montigny by Loverval as far as Châtelet. Detachments from the reserve cavalry were sent in the direction of Fleurus, to secure the I Corps from any molestation on the part of Grouchy; of whose proceedings nothing positive was then known at the Prussian headquarters.[17]

II Corps

On the evening of 18 June, Pirch I received orders to march from the field of Waterloo with his II Corps in the direction of Namur; for the purpose of turning Marshal Grouchy's left flank and intercepting his retreat upon the river Sambre.[18]

Pirch I made this movement during the night, passing through Maransart, where he was joined by his 7th Brigade; and crossing the (Dyle rivulet at Bousval,[lower-alpha 3] and also, subsequently, the Thyle, on his way to Mellery: which place he reached at 11:00 the following day.[lower-alpha 4] His corps was much divided on this occasion. He had with him the 6th, 7th, and 8th infantry brigades, and twenty four squadrons of cavalry: but the 5th Infantry Brigade, and the remaining fourteen squadrons, were with that portion of the Prussian army which was pursuing the French along the high road to Charleroi. The corps being greatly fatigued by the night march and its exertions on the previous day, Pirch I ordered the troops to bivouac and rest.[20]

During this march, Lieutenant-Colonel Sohr had pushed on with his cavalry brigade, as an vanguard; and now he was required intelligence concerning the movements of the French, and to seek a communication with Thielmann. He found the defile of Mont-Saint-Guibert strongly occupied by the French, but could obtain no information respecting Thielmann's corps.[20]

When it is considered how very near to Mellery the French IV Corps (Gérard's) must have passed, in order to fall into the Namur road at Sombreffe; it seemed extraordinary to William Siborne that Pirch I, who reached that place at 11:00 on 19 June — the same hour at which Grouchy, then beyond Wavre, received the first intimation of the defeat of Napoleon, — should have permitted Gérard to continue his retreat unmolested. Siborne concedes that Pirch's troops required rest; but comments that had Pirch maintained a good look out in the direction of Gembloux, he would, in all probability, after the lapse of a few hours, have been enabled to fulfil his instructions so far as to have completely intercepted the retreat of a considerable portion of Grouchy's army. That part of the French force which Lieutenant Colonel Sohr observed at Mont-Saint-Guibert, was probably the vanguard only of Gérard's corps since its rearguard remained at the bridge of Limal until nightfall. Stilbourn comments that taking all the circumstances into consideration, more especially the express object of the detached movement of the Prussian II Corps, it must be admitted that, on this occasion, there was a want of due vigilance on the part of General Pirch I.[21]

Evening

The blame for failure of the Prussians to comprehensibly destroy Grouchy's wing of the Army of the North was placed on Clausewitz, by his commander Thielmann and some historians such as Heinrich von Treitschke. As the Prussians started to disengage from the battle of Warvre, it was Clausewitz, Thielmann chief of staff, so Thielmann claimed, who was over cautious and continued to retreat until he found a suitable defensive position on the far side of Sint-Agatha-Rode, not realising that Grouchy far from pursuing them had himself on hearing the news from Waterloo started his own retreat. Treitschke argues that by losing contact with Grouchy, the Prussian III Corps (Thielmann's) was unable to harry the retreating French or send timely intelligence to the other Prussian commanders on the line of retreat that Grouchy was taking.[22]

It was not until nearly 17:00 on 19 June, that General Borcke, whose 9th Brigade, was still in the vicinity of Saint-Lambert,[lower-alpha 5] discovered the retreat of Grouchy's troops. He immediately communicated the fact to General Thielmann, who ordered him to cross the Dyle the next day (20 June) and march upon Namur. The French rearguard of Gerard's Corps continued to occupy Limal until nightfall. Thielmann remained posted, during the night of the 19/20 June, at Sint-Agatha-Rode;[lower-alpha 6] having his vanguard at Ottenburg.[18]

Wellington's army

At daybreak on 19 June, that portion of Wellington's army which had fought the Battle of Waterloo, broke up from its bivouac, and began to move along the high road to Nivelles. Those troops which had been posted in front of Hal[lower-alpha 7] during 18 June, consisting of 1st Dutch-Belgian Division (Stedman's), Dutch-Belgian Indies Brigade (Anthing's), and 1st Hanoverian Cavalry Brigade (Estorff's), under Prince Frederick of the Netherlands; as also the 6th British Infantry Brigade (Johnstone's), and the 6th Hanoverian Infantry Brigade (Lyons's), under Lieutenant General Sir Charles Colville, were likewise directed to march upon Nivelles.[14]

Wellington's army occupied Nivelles and the surrounding villages during the night of 19 June; in the course of which Wellington arrived from Brussels, and established his headquarters in the town.[14]

Armies dispositions evening 19 June

The general disposition of the respective armies on the evening of 19 June, was as follows:[23]

- The Prussian army, formed the southern (left) wing. The I Corps was at Charleroi; II Corps was on the march to Mellery, III Corps at Sint-Agatha-Rode; IV Corps at Fontaine-l'Évêque; and the 5th Brigade of the II Corps at Anderlues, near Fontaine-l'Évêque. Blücher's headquarters were at Gosselies.

- The Anglo-allied army, which constituted the north (right) wing of the advancing force, was at Nivelles and its vicinity. Wellington's headquarters were at Nivelles.

- The disorganized force of the main French army was in the vicinity of Beaumont, Philippeville, and Avesnes. Napoleon was travelling by coach towards Laon. The detached portion of the French army under Grouchy was on the march to Namur.

20 June

Political considerations

While at Nevilles Wellington issued a general order in which he made it clear to those under his command:

that their respective Sovereigns are the Allies of His Majesty the King of France; and that France ought, therefore, to be treated as a friendly country. It is therefore required that nothing should be taken, either by officers or soldiers, for which payment is not made.— Wellington, at Nevilles (20 June 1815).[24]

Wellington's reasoning for this was that it was in the interests of the powers of the Seventh Coalition, because he realised that it was expedient to persuade the bulk of the French nation that the Coalition armies came a liberators from the trinity of Napoleon's rule and not as conquerors. If the coalition forces were to treat the French and France as a hostile nation then the horrors which generally follow in the train of a victorious and lawless soldiery over the face of an enemy's country would make the subjugation of France more difficult and the French people were likely to view a restored Louie XVIII as a puppet of the victors rather than a legitimate government ruling with their consent. An unstable France would make a future war more likely.[24]

Anglo-allied advances

On the same day (20 June), Wellington, in consequence of a report received by him from Lieutenant-General Lecoq, and of a previous communication made to him by King Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, consented to take command of the Saxon Corps, amounting to nearly 17,000 men. He directed Lecoq to march these troops to Antwerp, and there await further orders.[25]

The Anglo-allied army marched to Binche and Mons. The British cavalry moved into villages between Roeulx and Mons. The 6th (Hussar) Brigade (Vivian's) took on the outpost duties on the Sambre. The Hanoverian Cavalry furnished outposts towards Maubeuge. Wellington placed his headquarters at Binche.[26]

Prussian advances and French retreats

Blücher, having secured the passage of the river Sambre in the neighbourhood of Charleroi, continued his pursuit of the French, and crossed the French frontier on 20 June. He directed Zieten to march the I Corps from Charleroi to Beaumont to throw forward his vanguard as far as Solre-le-Château, to detach a party of observation to the south-east (left) towards Florennes, and to watch the road from Philippeville to Beaumont.[27]

As the I Corps advanced, it discovered at every step fresh proofs of the extreme disorder in which the French army had retreated; and found twelve pieces of artillery which they had hitherto contrived to save from the great wreck at Waterloo, but had now abandoned to their pursuers. On arriving at Beaumont, the Corps took up a bivouac. Its vanguard, under General Jagow, consisting of the 3rd Infantry Brigade, the 1st Silesian Hussars, and a horse battery, reached Solre-le-Château upon the road to Avesnes.[28]

Blücher, at the same time, ordered Bülow to move the IV Corps as far as Colleret, where the road to Thuin intersects the high road from Beaumont to Maubeuge, and to push on his the vanguard to Beaufort, Nord. Bülow accordingly directed General Sydow to proceed with an vanguard, consisting of a cavalry brigade, a horse battery, and two battalions of infantry, which had the day before reached Leernes on the road to Thuin, and to ascertain very particularly whether the French had established themselves on the river Sambre, to secure the bridges both here and at Lobbes, and further, to restore these passages, should they have been destroyed by the French. Another detachment, under Colonel Eicke,[lower-alpha 8] consisting of two fusilier battalions, the two squadrons of cavalry attached to the 13th Brigade, and of the 2nd Silesian Hussars, was sent forward to take possession, in the first instance, of the passages of the river Sambre, and then to join General Sydow; who, proceeding by Colleret towards Beaufort, was to form both detachments into an vanguard on reaching the latter place. In the mean time, the mass of the IV Corps, headed by the reserve cavalry under Prince William of Prussia, followed in one column.[27]

The progress made by this portion of the Prussian army on 20 June was not so rapid as was desirable. Considerable delay arose in consequence of the degree of caution imparted to the movements by the impression which Bülow entertained that the French would defend the passages, and endeavour to maintain himself along the opposite side of the river. Hence the vanguard of the Corps only reached Ferrière-la-Petite; part of the main body proceeded as far as Montignies, and the remainder with the reserve artillery, did not get farther than the bridges across the Sambre.[30]

The 5th Brigade (belonging to the II Corps) had started at daybreak from its bivouac at Anderlues, near Fontaine-l'Évêque; and directed its march, by Binche, upon Villers-Sire-Nicole[lower-alpha 9] towards Maubeuge. The brigade was reinforced by 100 dragoons under Major Busch, and half a horse battery; which detachment arrived at Villers-Sire-Nicole at 17:00. This cavalry was employed in observing the Fortress of Maubeuge, from the Mons road, as far as the Sambre; and the brigade bivouacked at Villers-Sire-Nicole. A Hanoverian regiment of hussars also observed the fortress on the right of the Prussian cavalry upon the Bavay road.[31]

The left wing of the Prussian army, comprising the III, and part of the II Corps, came into contact with the French, while pursuing that part of the French army which was under Grouchy. Thielmann, having learned that the latter had commenced his retreat on Gembloux, marched at 05:00 from Sint-Agatha-Rode to Wavre; where he further ascertained that already on the afternoon of 19 June, the French had effected their retreat across the river Dyle, leaving only a rearguard on the left bank of the river.[31]

Grouchy, when he decided on retiring upon Namur, ordered General Bonnemains to move on rapidly, by Gembloux, with the 4th and 12th dragoons, as an vanguard, and to reach that town as soon as possible, and secure the passage of the Sambre. They were followed by the remainder of Excelmans' cavalry, and the reserve artillery, together with the wounded. The infantry was put in motion in two columns: the one, consisting of the II Corps, proceeding by Gembloux; and the other, comprising the IV Corps, passing more to the right, and falling into the Namur road in rear of Sombreffe. The light cavalry was principally with the rearguard. To deceive Thielmann, Grouchy left his rearguard in Wavre and Limale, with cavalry vedettes thrown out towards the Prussians, until near evening, when it followed the main body to Namur.[32]

Thielmann, having placed the whole of his cavalry, with eight pieces of horse artillery, at the head of his column, now ordered them to move on at a trot, for the purpose of overtaking the French; but it was not until they had passed Gembloux that they discovered the rearguard of Grouchy's force, consisting of a few regiments of cavalry. These, however, now made so rapid a retreat, that it was impossible to bring them to action.[33]

Action at La Falize

At length, on arriving near the village next to the Château La Falize (within about 3 miles (4.8 km) from Namur), the Prussians found Vamdamme's III Corps' rearguard posted on the brow of the declivity at the foot of which lay the town,[lower-alpha 10] in the valley of the river Meuse. It presented about two battalions of infantry, three regiments of cavalry, and four guns; and was formed to cover the retreat of the French troops.[33]

The Prussian battery immediately opened a fire; during which Colonel Marwitz, moving out to the right, with the 1st Cavalry Brigade, and Count Lottum to the left, with the 2nd, turned the French in both flanks. The latter brought forward a reserve of cavalry, when the 8th Prussian Uhlans, under Colonel Count Dohna, at the head of the column that turned the French left, made a most gallant attack upon the French dragoons; who met it with a volley from their carbines, but were overthrown. The 7th Uhlans and a squadron of the 12th Hussars also charged on this occasion, and captured three pieces of French horse artillery which were in the act of moving off, and also fifty cavalry horses. The French infantry now threw itself into the adjacent wood, with which the declivities that here lead down into the valley of the river Meuse are covered, and thus succeeded in preventing the Prussians from following up their success.[36]

Gérard's Corps retreat on Vandamme's rearguard

At this moment, intelligence was received that General Pirch was pursuing the French with the Prussian II Corps upon the high road leading from Sombreffe to Namur; whereupon the cavalry of the Prussian III Corps was moved in this direction. A French column, consisting of about twelve battalions and two batteries, but without any cavalry, was perceived marching along that road. They belonged to Gérard's IV Corps, which had effected its retreat by Limale, through Mont St Guibert. Upon the height on which the Château de Flawinne is situated was posted a detachment from Vandamme's Corps, consisting of from four to five battalions with a battery, and a regiment of cavalry, for the purpose of receiving Gérard's column as it fell back, and of protecting its retreat As the Enemy continued its retrograde march in close column and in good order; it was not deemed advisable to undertake an attack with the two Prussian cavalry brigades of the III Corps, which were much fatigued: but the horse battery was drawn up, and discharged several rounds of shell and grape at the French troops during their retreat upon the town. The latter, therefore, quitted the high road, and moved along the adjacent heights until they reached the battalions which had been drawn up in support, and which now opposed the further advance of the Prussians. At his juncture Thielmann's III Corps cavalry withdrew, leaving the engagement of the French to the Pirch's II Corps.[36][lower-alpha 11]

Action at Flawinne

It was not until 05:00 on 20 June that Pirch received intelligence that the French was retiring by Gembloux upon Namur. Lieutenant-Colonel Sohr was immediately detached, in all haste, to Gembloux with his cavalry brigade, a battery of horse artillery, and the fusilier battalions of the 9th, 14th, and 23rd regiments, as an vanguard. On approaching that town, Sohr ascertained that Thielmann's cavalry was pursuing the French along the high road from Gembloux to Namur. He therefore decided upon marching by the narrow road on the right of the chaussée leading from Sombreffe, in full trot, covered by woodland, to overtake the French troops in retreat. At Temploux, the latter presented a force of two battalions, some cavalry, and four pieces of artillery in position, prepared to cover the retreating column. Sohr immediately attacked with both the regiments of hussars, supported by the battery of horse artillery; and defeated this portion of the French force. It was at this moment, too, that a cannonade was opened upon the latter by the horse battery, before mentioned, of Thielmann's Corps; whereupon the French fell back upon the favourable position taken up near Flawinne,[lower-alpha 12] and in which the French appeared determined to make a stand.[38]

Pirch immediately ordered the attack, and directed that it should be supported by Major-General Krafft with the 6th Brigade, which had closely followed the vanguard, and had come up with the latter at 16:00. Three columns of attack were formed. The first consisted of the 1st Battalion of the 9th Regiment, the Fusilier Battalion of the 26th Regiment, and the 1st Battalion of the 1st Elbe Landwehr. It was under the command of Major Schmidt, and detached to the left of the road, to drive back the French troops posted in the woodland and upon the heights. The second consisted of the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 26th Regiment, and the 2nd Battalion of the 9th Regiment, under Colonel Reuss, and of the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Elbe Landwehr, under Colonel Bismarck. This column, which advanced partly on the right, and partly on the left, of the road, was supported by the Battery No 5, and led by Major-General Krafft in person. The third column comprised the fusilier battalions which had constituted the infantry of the vanguard; and was detached more to the right, towards the Sambre, to support the general advance upon Namur.[39]

General Krafft, after a short bombardment upon the French with his artillery, ordered the attack with his infantry. Colonel Reuss threw out his skirmishers, who were quickly followed by the columns of attack. The French, after some little resistance, were driven into Namur by a charge with bayonets, and suffered much loss.[40]

In the mean time, Major Schmidt, with his column of three battalions, had turned the right flank of the French on the Louvain road; and so the French were now limited to the defence of the Namur suburbs, which, however, they maintained with great obstinacy.[40]

Action at Namur

The Prussian columns of attack, advancing at the pas de charge (at the double), drove the French out of the Namur suburb, and endeavoured to gain possession of the gates of the town. Colonel Zastrow, the second in command of the Sixth Brigade, wished to burst open the gate which leads to the Louvain road; but was repulsed by a most murderous fire of musketry and grape, directed upon the assailants from then walls of the town.[40]

On repeating the attempt, the Prussian battalions fought with distinguished bravery, but with a great sacrifice of life. Colonel Zastbow was killed at their head; Colonel Bismarck also fell; Colonel Reuss was wounded; and the 6th Brigade alone lost 44 officers, and 1,274 other ranks.[41]

The main body of Grouchy's Army was at this time in full retreat upon Dinant, along the Defile of the Meuse. The French troops left in Namur, to keep the Prussians at bay as long as possible, consisted of General Teste's division. They carefully barricaded all the gates, lined the walls facing the Prussians, and made a most gallant resistance. The officers, finding that their men continued so perfectly steady as not to require their attention, armed themselves with the muskets of the wounded, and assisted in maintaining the fire from the walls. The greatest order prevailed in the town. The wounded, the provisions, and ammunition, had already been removed; and were on the line of march.[42]

General Pirch was well aware that the French defended the town solely for the purpose of covering their retreat, and had therefore no intention of undertaking any serious attack; he simply wished to possess himself of the suburbs, and to hold the French in check by detaching troops to the Porte de Fer (Iron Gate) and the St Nicholas Gate. He thought that a demonstration against the latter gate would raise apprehensions in the minds of the French respecting the security of the bridge over the Sambre.[42][43]

With this view, he ordered General Brause to relieve, with the 7th Brigade, the troops then engaged; and together with the vanguard under Lieutenant Colonel Sohr, to blockade the town. At the same time he directed the remainder of the Corps to bivouac near Temploux.[42]

General Brause proceeded to post the Fusilier Battalion of the 22nd Regiment in the direction of the Porte de Fer, and the Fusilier Battalion of the 2nd Elbe Landwehr towards the Brussels Gate. The main body of the 7th Brigade, under Colonel Schon, was stationed in rear of the suburb. The first mentioned battalion stood, under cover, at four hundred paces distance from the Porte de Per, having its Tirailleurs in the avenue near the gate. Just as General Brause rode up to examine its formation, an alarm was spread in front that the French was making a sortie. The General desired the commanding officer, Major Jochens, to lead his battalion quickly against the defenders, to overthrow them, and then, if possible, to penetrate into the town along with the retreating troops. As Major Jochens approached the gate, he found in its immediate vicinity the Tirailleurs of the 6th Brigade, still maintaining the contest in that quarter. The attacking column and the Tirailleurs now rushed towards the gate and the walls; which the French, probably not deeming themselves strong enough to resist this pressure, abandoned in the greatest haste.[44]

General Teste had, in fact, prepared everything for his retreat; and had so well calculated the time which the Prussians would require in forcing an entrance by the Porte de Fer, that he succeeded in filing his battalions along the parapets of the bridge, which had been barricaded, and thus withdrew them to the south bank of the Sambre. The Prussians found it impossible to force open the gate. The windows of the adjoining house of the Douanitrs (custom officers) were therefore driven in, and a small iron door which led from the interior of the house into the town was opened, and, in this manner, an entrance was effected for the assailants; who were conducted by Major Jochens, of the 22nd, and Major Luckowiz, of the 9th Regiment, across the Market Place, and as far as the bridge over the Sambre: which the French had barricaded, as before stated, and behind which they had again established themselves. These troops were closely followed by Major Schmidt, with the 9th Regiment, and lastly by the 2nd Elbe Landwehr, in close column, under Majors Mirbach and Lindern.[45]

The Prussians immediately occupied the captured portion of the town; posted a column of reserve on the Market Place, and with loud cheers, made themselves masters of the bridge over the Sambre. An attempt had been made to gain the rear of the French, by means of a ford in this river; but it proved unsuccessful.[46]

The French were driven with so much impetuosity towards the gate leading out to Dinant, that there appeared every probability of a considerable number of them falling into the hands of the Prussians. The former, however, had heaped up large bundles of wood, intermingled with straw and pitch, against the gate, and set them on fire on the approach of the Prussian troops. The gate and the street were soon in flames, and the pursuit was thus obstructed; but even had this not occurred, the great fatigue of the Prussian troops who, during the previous sixteen hours, had been either marching or fighting, was sufficient to deprive them of the power of following the retreating French with any degree of vigour.[46]

After 21:00, the town was in the possession of the Prussians. Major Schmidt took the command at the Dinant Gate and Major Jochens at the bridge over the Sambre. The remaining troops of the 7th, and some battalions of the 6th Brigade were posted by General Brause upon the market place. The Fusilier battalions of the vanguard, which had supported the attack, more to the right, had also advanced into the town, towards the bridge over the Sambre. They had been sharply cannonaded by the French from the east bank of the Sambre.[46]

Aftermath—Grouchy's retreat by Namur on Dinant

In his report to Napoleon written in Dinant, 20 June, Marshal de Grouchy explained why he ordered a substantial holding operation at Namur:

... We entered Namur without loss. The long defile which extends from this place to Dinant, in which only a single column can march, and the embarrassment arising from the numerous transports of wounded rendered it necessary to hold for a considerable time the town, in which, I had not the means of blowing up the bridge. I entrusted the defence of Namur to General Vandamme, who, with his usual intrepidity maintained himself there till eight in the evening; so that nothing was left behind, and I occupied Dinant.The enemy has lost some thousands of men in the attack on Namur, where the contest was very obstinate; the troops have performed their duty in a manner worthy of praise.[47]

A small party of cavalry, under Captain Thielmann, of the Pomeranian Hussars, was sent forward a short distance on the road to Dinant, to form the advance of the troops destined to pursue the enemy at daybreak.[48]

General Teste's division retired slowly, and in good order, by the Dinant road, as far as Profondeville. where it took up a position during three hours. At midnight it resumed its march, and arrived at Dinant at 04:00 on the following morning.[48]

In the view of the military historian William Slbourn this retreat of Grouchy by Namur upon Dinant was executed in a skilful and masterly manner; and the gallant defence of the former town by General Teste's Division, unaided by artillery, merits the highest commendation.[48]

In this action the Prussians suffered a loss, including that already mentioned as having occurred to the 6th Brigade, of 1,500 men; and the French are supposed to have lost about the same number. In the last attack, the latter abandoned 150 prisoners they had previously taken from the Prussians.[48]

The Prussian II Corps during the night. The cavalry of the III Corps bivouacked at Temploux; the infantry of the latter (which had been rejoined on the march from Wavre by the 9th Brigade), near the town of Gembloux.[48]

The circumstances under which the French army, generally, was placed on 19 June rendered it sufficiently obvious that Grouchy would be compelled to effect his retreat by Namur; and further, that whatever show of resistance he might offer on that point would be solely intended to gain time for the security of his troops whilst retiring, in one column only, by the long and narrow defile of the river Meuse which leads to Dinant. Aware that Napoleon's defeated army was retiring along the direct line of operation, the Charleroi road; he immediately saw the imminent risk of his own retreat becoming intercepted, and the consequent necessity of his effecting the latter in a parallel direction, with a view to his rejoining the main army as soon as practicable. To retire, therefore, by Geinbloux upon Namur, and thence along the line of the Meuse, by Dinant and Givet. In the view of Slbourn this naturally presented itself as the true and proper course to be pursued.[49]

To generals in command of corps, such as Thielmann and Pirch, a little reflection upon Grouchy's critical position must have led to a similar conclusion. The inactivity of the Thielmann, during the afternoon and evening of 19 June, is probably to be explained by his having satisfied himself that the longer Grouchy continued in the vicinity of Wavre, the greater became the chance of his retreat being cut off by a portion of the Coalition armies; which, in their advance, would reach the Sambre much sooner than it would be in the power of the French marshal to do: and that, therefore, it would he injudicious on his part to attempt to force the latter from the position, which appearances induced him to believe he still occupied with his entire force, on the Dyle. He may also have been strengthened in this opinion by the circumstance of his not having received any positive instructions as to his future dispositions, or any reinforcements to secure for him a preponderance over Grouchy.[50]

With Pirch, however, the case was very different. He received distinct orders, on the evening of 18 June, to march at once from the battlefield of Waterloo, and continue his movement during that night, so as to cut off Grouchy's retreat upon the Sambre. However (it has already been explained), that on reaching Mellery at 11:00 on the following morning, he halted to give his troops rest; that be subsequently ascertained, through Lieutenant Colonel Sohr, who had been despatched, during the march, with his cavalry brigade to reconnoitre on the left, that the French occupied the defile of Mont-Saint-Guibert in force.[50]

In Sibourn's opinion this intelligence might have satisfied Pirch that Grouchy had not yet reached Namur; but, if he entertained any doubts on that point, these could easily have been settled by means of a reconnoitring party, detached from Mellery, by Gentinnes and Saint-Géry, to Gembloux, a distance of 7 miles (11 km). He would then have learned, that no portion whatever of Grouchy's force had by then crossed this line, in retreat; that he had, consequently, gained considerably on his rear, and had it in his power, after allowing a few hours rest to his troops, to march them by the high road which leads directly from Mellery into the high road near Sombreffe, and to anticipate Grouchy in the possession of Namur.[51]

What might have been

In this case, Grouchy, on approaching the latter place, and finding it occupied by Pirch, would, in all probability, have hesitated to risk the loss of so much time as an attempt to force the town and the Pont de Sambre (Sambre Gate) would necessarily incur, and have preferred endeavouring to pass his troops across the Sambre by some of the bridges and fords between Charleroi and Namur, and retire upon either Philippeville or Dinant; but with a Prussian Corps at each of these points, and another in his rear, this would have been, a most hazardous undertaking, and if he attempted to cross the Meuse below Namur, his chance of regaining Napoleon's army would have been still more remote.[52]

But setting aside the circumstance of Pirch's not having, in this manner, taken due advantage of the position in which he stood relatively with Grouchy during 19 June; and passing to the fact, that he first learned, at 05:00 on 20 June, whilst still at Mellery, that the French were retiring along the high road from Gembloux to Namur, pursued by Thielmann's cavalry: it seems strange that, inferring, as he must naturally have done, that Grouchy would only endeavour to hold out long enough at Namur to effect his passage by the Pont de Sambre, and to cover his retreat to Dinant, he did not immediately move off by his right, and push his troops across the Sambre by some of the bridges and fords higher up the stream; and then, marching in the direction of Profondeville, under cover of the woods within the angle formed by the confluence of the Sambre and the Meuse,[lower-alpha 13] intercept Grouchy's retreat through the long and narrow defile in which the road to Dinant winds in the Meuse valley. The situation in which Grouchy would have been placed by a movement of this kind — his troops in a long, narrow, precipitous defile, obstructed in front by Pirch, and attacked in rear by Thielmann — would have been perilous in the extreme.[53]

Pirch probably felt that his corps, part of which was then attached to the army pressing the French by the Charleroi road, was not equal to cope with Grouchy's troops; but in the case here supposed, by judiciously disposing his force then present so as to command the defile at some favourable point in its course, he would have secured for himself an advantage which, under such circumstances, would have fully compensated for his deficiency in regard to numbers.[53]

Napoleon proceeds to Paris

The scattered remnants of the main French army continued to be hurried forward in wild confusion across the frontier. Some of the fugitives hastened towards Avesnes to Philippeville: whilst a very great proportion of them sought no temporary rest of this kind, but, throwing away their arms, tied into the interior, to return to their homes; the cavalry, in many instances, disposing of their horses to the country people. Several of the superior officers hastily collected such of the troops as appeared better disposed, and conducted them in the direction of Laon. Napoleon reached the latter town in the afternoon of 20 June. After conferring with the Prefet, he desired de Bussy, an aides de camp, to superintend the defence of this important place; and despatched General Dejean to Avesnes, and General Flahaut to Guise.[54]

In the mean time, a body of troops had been discerned in the distance, moving towards the town. Napoleon sent an aide de camp to reconnoitre it; when it proved to be a column of about 3,000 men, which Soult, Jerome, Morand, Colbert, Petit, and Pelet had succeeded in rallying and preserving in order. Napoleon now appeared intent upon remaining at Laon until the remainder of the army had reassembled: but he subsequently yielded to the force of the arguments expressed in opposition to this determination by the Duke of Bassano and others who were present, and took his departure for Paris; purposing, at the same time, to return to Laon on the 25th or 26th of the month.[54]

Armies dispositions evening 20 June

The following was the general disposition of the respective armies on the evening of 20 June.[55]

Blücher's headquarters were at Merbes-le-Château. The Prussian army had its I Corps at Beaumont; IV Corps at Colleret; II Corps at Namur, with the exception of the 5th Brigade, which was on the march to blockade Maubeuge, and bivouacked at Villers-Sire-Nicole; III Corps was at Gembloux, with its cavalry bivouacked at Temploux.[55]

The Duke of Wellington's headquarters were at Binche. The Anglo-allied army had its right at Mons, and its left at Binche. The British cavalry was cantoned in the villages of Strepy, Thieu, Boussoit-sur-Haine, Ville-sur-Haine, and Goegnies;[56] Vivian's 6th Brigade in those of Merbes-Sainte-Marie, Bienne-lez-Happart, and Mont-Sainte-Geneviève and the Hanoverian cavalry in those of Givry and Croix-lez-Rouveroy. The reserve was at Soignies.[57]

Napoleon had left Laon for Paris. The French army retreating was completely dispersed. A few of the troops took refuge in Avesnes, others in Guise, and the principle body of them evidencing any kind of order, (but not exceeding 3,000 men), had reached Laon. The French forces under Grouchy were at Dinant.[55]

21 June

On 21 June the French army continued collecting its scattered remnants between Avesnes and Laon.[58]

The Duke of Wellington crossed the French frontier, moving the principal portion of his army to Bavay, and the remainder from Mons upon Valenciennes, which Fortress was immediately blockaded; and established his headquarters at Malplaquet, celebrated as the scene of the victory gained by the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene over the French under Marshals de Villars and Boufflers on 11 September 1709.[55]

Triple line of French Fortresses

Both the Coalition Commanders had now reached the Triple Line of Fortresses, which, until the Campaign of 1814 proved the contrary, had been considered by so many military men as presenting an insurmountable barrier to the advance of hostile armies into France by its north-eastern frontier. It was most essential that some of the principal fortresses should be secured; and made to constitute a new basis whence to direct the operations now contemplated against the interior. The following, which first presented themselves on the respective lines of advance of the two Commanders, were destined to be immediately blockaded: Valenciennes, Le Quesnoy, and Cambrai, by the Anglo-allied army; and Maubeuge, Landrecy, Avesnes-sur-Helpe (Avesnes), and Rocroi, by the Prussians. The general arrangements for the besieging of the fortresses, and the planning of the further operations, above alluded to, were to form the subject of a conference to be held very shortly between the two commanders (see below § Conference at Catillon).[59]

Blücher having, on this day, received reports from Pirch and Thielmann, detailing their proceedings during the two previous days, and showing that Grouchy had succeeded in effecting his escape by Dinant, immediately ordered that the II Corps should move upon Thuin, and place itself under the orders of Prince Augustus of Prussia; who was to undertake the besieging of the fortresses to be left in rear of the Prussian army; and that the III Corps should march by Charleroi, and follow the I and IV Corps as a reserve.[59]

Captain Thielmann had been sent forward from Namur, with a party of the Pomeranian Hussars, on the night of 20 June, a short distance along the road to Dinant. He was joined at daybreak of 21 June by Lieutenant Colonel Sour, with the fusilier battalions of the 14th and 23rd Regiments, the Brandenburg and Pomeranian Hussars, and five pieces of horse artillery; when the whole force followed the French towards Dinant. Grouchy had, during his retreat, seized every favourable opportunity in narrow and rocky parts of the defile, to barricade the road, and offer every obstruction to the pursuit: by means of which precaution, and the previous night march, the French contrived to gain so considerably in advance, that Lieutenant Colonel Sorb deemed it prudent, when near Dinant, to forego all further pursuit; and to endeavour to effect a junction with the main body of the Prussian army, by moving upon Florennes and Walcourt. At the former place he halted his detachment during the night of 21 June; and, in this manner, covered the left flank of the main Prussian army.[60]

Anxious to gain intelligence concerning the assembling and marching of the French troops on the left of the Coalition armies, Blücher despatched Major Falkenhausen, with the 3rd Regiment of Silesian Landwehr Cavalry, to scour the country in the vicinity of the road by Rettel to Laon. A detachment of fifty dragoons was posted at Boussu-lez-Walcourt, in observation of Philippeville.[61]

The Prussuan IV Corps (Bülow's) was ordered by Blücher to advance, as far as Maroilles, upon the road from Maubeuge to Landrecies. Its vanguard, under General Sydow, was directed to proceed still further, and to blockade the latter fortress.[61]

Capture of Avesnes

Zieten, in pursuance of orders which he had received the night before, marched with the I Corps upon Avesnes; which fortress, the vanguard, under General Jagow, was directed to blockade on both sides of the river Helpe Majeure. The march of the Corps was made in two columns: the right, consisting of the 1st and 2nd Brigades, proceeded by Semousies, and halted at the junction of the road from Maubeuge with that from Beaumont to Avesnes; the left, comprising the 4th Brigade, the reserve cavalry, and the reserve artillery, marched by Solre-le-Château, towards Avesnes, and bivouacked near the 1st and 2nd Brigades. Two companies of the 4th Brigade, with twenty dragoons, were left to garrison Beaumont; but after the capture of Avesnes, they were ordered to move on to the latter place.[61]

It was between 15:00 and 16:00 when the vanguard of the 3rd Brigade, consisting of the 1st Silesian Hussars, two rifle companies, and a fusilier battalion, arrived in front of the Fortress of Avesnes. The Commandant having rejected Zieten's summons to surrender, the latter ordered the bombardment to be commenced forthwith. Ten howitzers, of which six were ten pounders, and four seven pounders, drew up on the flank of the cavalry, and fired upon the town. The houses of the latter being all strongly built, the shells failed in setting any part on fire; and a twelve pounder battery produced no great effect upon the firm masonry of the works. At nightfall the bombardment was suspended; with the intention, however, of resuming it at midnight. When it ceased, a sortie was made by the French tirailleurs; but these were immediately encountered and driven back in by the Silesian Rifles, who lost ten men on this occasion.[62]

Immediately after midnight, the Prussian batteries recommenced their fire. At the fourteenth round, a ten pounder shell struck the principal powder magazine, when a tremendous explosion ensued, by which forty houses were involved in one common ruin; but it occasioned no damage whatever to the fortifications. The panic, immediately after the explosion created amidst the garrison was such as to induce the Commandant to surrendered at discretion of the Prussians without attempting to seeking terms. Such a desire could only have proceeded from the want of sufficient energy on the part of the Commandant, or from a bad disposition evinced by the garrison, for when the Prussians subsequently entered the place, they found in it 15,000 cartridges for cannon, and a million musket ball cartridges. There were also in the fortress forty seven pieces of artillery, mostly of heavy calibre; which were now made available in the besieging of the remaining fortresses. The garrison, 400 of whom were killed in the explosion comprised three battalions National Guards and some veterans (of whom 239 National Guards, and 200 veterans survived the explosion). The National Guards were disarmed, and sent off to their respective homes; but the veterans were conducted to Cologne.[63][64][lower-alpha 14]

The possession of Avesnes, gained too with so little sacrifice of life, and with none of time, was of essential importance to the Prussians; offering as it did a secure depot for their material and supplies upon their new line of operation. It also served for the reception of their sick, and all who had been rendered incapable of keeping up with the army.[58]

Armies dispositions evening 21 June

The following was the general disposition of the respective Armies on the evening of 21 June:[58]

The Prussian army

- The I Corps near Avesnes-sur-Helpe.

- The IV Corps at Maroilles, its reserve cavalry blockading Landrecy.

- The II Corps at Thuin, except the 5th Brigade which blockaded Maubeuge.

- The III Corps at Charleroi.

- Blücher's headquarters were at Noyelles-sur-Sambre.

The Anglo-allied army

- The principal force at Bavay;

- The right wing at Valenciennes, which it blockaded.

- Wellington's headquarters were at Malplaquet.

The defeated portion of the French army lay between Avesnes and Laon.

- Grouchy's force was at Philippeville.

Malplaquet proclamation

While at Malplaquet Wellington, steadfastly pursuing that line of policy which led him to constitute as an important feature of his plan, the practical assurance to the French people, that, although entering their country as a conqueror, he did so in hostility to none, save the "usurper Napoleon Bonaparte and his adherents",[58] issued a Proclamation that Napoleon Bonarparte was an usurper and that Wellington's army came a liberators not as enemy invaders and that he had issued orders to his army that all French citizens who did not oppose his army would be treated fairly and with respect.[65]

In the opinion William Siborne and C.H. Gifford during the advance to Paris, a marked contrast was observed between the conduct of the Prussian and the Anglo-allied armies. The troops of the former committing great excesses and imposing severe exactions along their whole line of march; whilst the British and German troops under Wellington acquired from the outset the good will and kindly disposition of the inhabitants of the country through which they passed. The Anglo-allied troops inspired the people with confidence, while the Prussians awed them into subjection.[65][64][lower-alpha 14]

22 June

On 22 June, the 2nd and 4th British divisions, as also the cavalry, of the Anglo-allied army marched to Le Cateau and its vicinity. The 1st and 3rd British divisions, the divisions of Dutch-Belgian infantry attached to the I Corps, the Nassau troops, and the Dutch-Belgian cavalry were encamped near Gommegnies. The 5th and 6th British divisions, the Brunswick Corps, and the Reserve Artillery, were encamped about Bavay. The vanguard (Vivian's Brigade) was at Saint-Benin. Troops of the Corps under Prince Frederick of the Netherlands blockaded Valenciennes and Le Quesnoy. The Duke of Wellington's headquarters were at Le Cateau.[66]

Blücher being desirous of bringing his different Corps into closer contact, moved the I and IV only half a march this day. The former proceeded from Avesnes to Étroeungt, sending forward its vanguard to La Capelle, and patrols as far as the Oise: the latter marched along the road leading from Landrecy towards Guise, as far as Fesmy-le-Sart pushing forward its vanguard to Hannapes, and detachments to Guise. Scouring parties of cavalry were also detached from the I Corps in the direction of Rocroi.[66]

The Prussian III Corps advanced from Charleroi to Beaumont; detaching towards Philippeville and Chimay, for the security of its left flank.[66]

The Prussian II Corps (Pirch's), which was destined to operate against the fortresses, moved from Thuin. It was disposed in the following manner: The 5th and 7th brigades, with the cavalry, blockaded Maubeuge; the 6th Brigade was on the march to Landrecy and the 8th Brigade was moving upon Philippeville and Givet.[67]

Blücher's headquarters were at Catillon-sur-Sambre.[67]

Grouchy's troops, reached Rocroi. The remains of the vanquished portion of the French army continued retiring upon Laon, and collecting in its vicinity. Soult had established the headquarters at this place. The men and horses of the artillery train were moved on to La Fère, to be supplied with new ordnance; and every means was adopted to replace this branch of the service on an efficient footing. Grouchy was effecting his retreat upon Soissons, by the line of Rocroi, Rethel, and Rheims; and it was considered, that as soon as the latter should be able to unite his force to the remains of the army collecting under Soult, it would then be found practicable, with the additional aid of reserves, to stem the advance of the Allies.[67]

William Siborne puts forward an alternative choice that Napoleon could have made instead of returning to Paris in an attempt to shore up his political position. Siborne speculates that if he had instead headed for General Rapp and his V Corps (Armée du Rhin) cantoned near Strasbourg, and called on General Lecourbe to bring his I Corps of Observation (Armée du Jura) based at Belfort, to his aid this would form thae nuclease of a new army to which he could summon all the reserves that he could possibly collect together, including the Regimental Depots, the Gensd' armerie and even Douancric. With this force he could have attacked the flanks of the victorious armies of Wellington and Blücher, during their hazardous advance upon Paris; and, in combination with Soult and Grouchy, to effect the allies separation, and perhaps their destruction.[68]

23 June

On 23 June, Wellington and Blücher gave to the great mass of their troops a halt; not merely for the sake of affording them rest, but also for the purpose of collecting the stragglers, and bringing up the ammunition and the baggage.[69]

The only movement made on the part of the Anglo-allied army, was that by Major General Lyon's 6th Hanoverian Brigade, which, together with Grant's Hussar Brigade, Lieutenant Colonel Webber-Smith's Horse Battery, Major Unett's and Major Brome's foot batteries, marched, under the personal command of Sir Charles Colville, to attack Cambrai, the garrison of which, Wellington had been led to believe, had abandoned the place, leaving in it at most 300 or 400 men. Colville was furnished with a letter from Wellington to the Governor, summoning him to surrender; as also with some copies of Wellington's Proclamation of 22 June to the French. The 1st Brunswick Light Battalion was sent forward from the reserve at Bavay, to watch Le Quesnoy; the fortress of which was still occupied by the French.[69]

The Prussian III Corps was pushed forward to Avesnes, by which means the three Prussian Corps destined to advance upon Paris were so placed that they could form a junction, with only half a day's ordinary march; and this relative position was maintained throughout the remainder of the line of advance.[70]

Conference at Catillon

The Coalition Commanders met at Catillon, for the purpose of arranging their plan of combined operations. The intelligence they had procured having satisfied them that the French was collecting their forces at Laou and Soissons: they decided upon not pursuing them along that line, since their own progress towards the capital might, in that case, be impeded by affairs of advanced and rearguards; but upon moving by the right bank of the Oise, and crossing this river at either Compiègne or Pont-Sainte-Maxence. By thus turning the French left, they hoped to intercept the French army's retreat, or at all events to reach Paris before it; and in order to deceive the French as to these intentions, their army was to be followed by Prussian cavalry, and hopefully tricking the French into assuming the cavalry be the vanguard of the Collation armies.[71]

It was also settled, that as they might find it necessary to throw bridges across the Oise, the British general should bring forward his Pontoon Train as that possessed by the Prussians was inadequate for the purpose.[71]

In order to secure a good base from which to conduct these operations, it was further arranged that the corps under Prince Frederick of the Netherlands should remain, for the purpose of besieging the fortresses situated on the Scheldt, and between that river and the Sambre: and that the Prussian II Corps commanded by General Pirch I; the German Corps, commanded at first by General Nollendorf, and subsequently by Lieutenant General Hake; as also a portion of the garrison troops of Luxemburg, commanded by Lieutenant General Prince Louis of Hesse-Homburg, — the whole of these German forces being placed under the chief command of Prince Augustus of Prussia — should undertake the besieging of the fortresses on the Sambre, and those between the Sambre and the Moselle.[72]

This plan of operations was such as might have been expected from the combined councils of such leaders as Wellington and Blücher, and was undoubtedly the one best calculated to attain the object they had in view; and it was carried into effect with all that mutual cordiality and good fellowship which had invariable-characterised their proceedings.[73]

James Haweis makes the point that although the Blücher kept the three corps which he was to lead to Paris within half a day's ordinary march of each other, the Anglo-allied army and the Prussians were separated by more than a day and that:[74]

[t]he reason for the comparative slowness of Wellington's advance compared with Blucher's is not evident. Had the Napoleon of 1814 commanded the army at Soissons on the 26th, he might once more have delivered against the extended and unsupported Prussians the lightning-like strokes which then paralysed his enemies, though success, as in the former campaign, could only have retarded, not averted, the final disaster.

24 June

Anglo-allied operation

Storming and surrender of Cambrai

On the morning of 24 June, the Duke of Wellington, in consequence of a report which he had received from Sir Charles Colville, directed Lord Hill to march the two brigades of the 4th Division then at Le Cateau, towards Cambrai, where they would join the other brigade of the division; and also to send with them a nine pounder battery.[73]

On the arrival of these troops, Colville made his preparations for the attack; which took place in the evening, in the following manner. three columns of attack were formed. One commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Sir Neil Campbell (Major in the 54th Regiment), escaladed at the angle formed by the Valenciennes Gateway and the Curtain of the body of the place. A Second, commanded by Colonel Sir William Douglas, of the 91st Regiment, and directed by Lieutenant Gilbert of the Royal Engineers, escaladed at a large ravelin near the Amiens road. A third, consisting of Colonel Mitchell's 4th Brigade, and directed by Captain Thompson of the Royal Engineers, after having forced the Outer Gate of the couvre port (covered gate) in the hornwork, and passed both ditches, by means of the rails of the drawbridges, attempted to force the main Paris Gate; but not succeeding in this, it escaladed by a breach on that side, which was in need of repair. The three batteries of Lieutenant Colonel Webber-Smith, and Majors Unett and Brome, under the direction of Lieutenant Colonel Hawker, rendered the most essential service in covering these attacks; which having succeeded, the town speedily fell into the hands of the assailants. The citadel continued to hold out, but the Governor solicited a suspension of hostilities; which, however, could not be granted.[75][76]

On 25 June Louis XVIII, at the suggestion of Wellington, despatched an officer, Le Comte d'Audenarde, with a summons, in the name of Louis XVIII, for the governor, Baron Noos,[lower-alpha 15] to surrender the Citadel of Cambrai. The summons was obeyed, the garrison capitulated and Wellington immediately handed the fortress to Louis XVIII.[77] The Anglo-allied army casualties during the assault were eight killed and 29 wounded.[78]

Other movements

Of the Anglo-allied army, the 1st and 3rd British divisions, the Dutch-Belgian infantry attached to the I Corps, and the Dutch-Belgian cavalry, moved from Gommignies, to Forest-en-Cambrésis, upon the road to Le Cateau, and then encamped between the villages of Croix-Caluyau and Bousies. The 2nd British Division continued at Le Cateau.[79]

The reserve, consisting of the 5th and 6th divisions, of the Brunswick Corps, and the reserve artillery, was moved nearer to the main body; and cantoned and encamped in and about the villages of Englefontaine, Rancourt, and Preux-au-Bois.[lower-alpha 16][79]

Wellington remained at Le Cateau; having found it expedient to wait for supplies and for the pontoons to arrive.[79] Louis XVIII, acting on the advice so urgently tendered to him by Wellington, arrived at Le Cateau late in the evening of 24 June, followed by a numerous train; and only awaited the surrender of the Citadel of Cambari to take up temporary residence in the town.[80]

Prussian operations

The Prussian army renewed its operations on 24 June, according to the plan agreed upon the day before by the Coalition commanders. At break of day, Lieutenant Colonel Schmiedeberg was despatched with the Silesian Regiment of Uhlans, and some horse artillery, towards Laon; for the purpose, in conjunction with the detachments already sent from the Prussian I Corps, of watching and deceiving the French. Blücher disposed his three Corps in two Columns. The left column, which was the one nearest to the French, consisted of the I and III Corps; and was to move close along the river Oise — the III Corps remaining half a march in rear of the I. The right column, formed by the IV Corps, was to advance along a parallel road, keeping on a line with the former, and at the distance of about half a march. The left column moved upon Compiègne, the right upon Pont-Sainte-Maxence.[81]

Capture of Guise

At 09:00, the I Corps (Zieten's) commenced its march from Étroeungt towards Guise. The vanguard, under Major General Jagow, to which were attached the 8th Foot Battery, and two ten pounder howitzers, halted when opposite to Saint-Laurent, a suburb of Guise, in order to observe the fortress on the north-east side; whilst Zieten sent an infantry brigade, a regiment of cavalry, together with a horse, and a foot, battery, by Saint-Germain and Rue de la Bussière (in Flavigny-le-Grand-et-Beaurain), across the Oise (the locations of the closest down stream and up stream bridges from Guise), to menace the place from the other side.[82]

The French commandant, on finding himself completely invested, withdrew his troops into the citadel; whereupon preparations were immediately made by the Prussians to open their batteries against that part, but previously to giving the order to commence the cannonade, Zieten sent a summons to the commandant to surrender; with which the latter did not hesitate to comply. The garrison, consisting of eighteen officers and 350, laid down their arms on the glacis, and were made prisoners of war. The Prussians found in the place, fourteen pieces of cannon, 3,000 muskets, two million musket ball cartridges, a quantity of ammunition, and considerable magazines; and gained, what was of more importance, another strong point in their new base of operations, without having fired a single cannon shot. Major Müller, with the two weak fusilier battalions of the 28th Regiment, and of the 2nd Westphalian Landwehr, were ordered to garrison the place.[82]

Other movements

As soon as the remainder of I Corps (Zieten's) arrived near Guise (which was before the place surrendered), the vanguard, consisting of the 3rd Brigade, moved on, but did not reach Origny before 21:00. The 1st Regiment of Silesian Hussars pushed on as far as Ribemont. Parties were also detached from the reserve cavalry towards Crecy, Pont-à-Bucy[lower-alpha 17] (in Nouvion-et-Catillon), and La Fère, to observe the river Serre.[83]

Thielmann, with the Prussian III Corps, moved from Avesnes upon Nouvion; which he reached about 16:00. The detachments of observation which had been previously sent out to the left from this Corps, to endeavour to gain intelligence concerning Grouchy's army, reached Hirson and Vervins in the evening. Scouring parties were also sent towards the road leading from Charleville-Mézières by Montcornet towards Laon.[84]

Bülow, with the IV Corps, which formed the right Prussian column, marched from Fesmy-le-Sart[lower-alpha 18] to Aisonville-et-Bernoville. Parties of cavalry, detached from the Corps, reached Châtillon-sur-Oise, and found Saint-Quentin unoccupied. This circumstance having been made known to General Sydow, upon his arrival at Fontaine-Notre-Dame with the vanguard, he pushed on, and took possession of that important town. A detachment of from five hundred to six hundred French Cavalry had marched from this place on the previous day towards Laon. The troops which had been employed in the investment of Landrecies rejoined the IV Corps on this day.[84]

By means of these movements, and of the halt of Wellington at Le Cateau, the Prussians were a day's march in advance of the Anglo-allied army.[84]

French proposals for a suspension of hostilities

During the day proposals were made by the French to the advanced posts of the Brunswick Corps under Prince Fredrick of the Netherlands near Valenciennes, as also to those of the Prussian I Corps, for a suspension of hostilities, upon the grounds that Napoleon had abdicated in favour of his son; that a Provisional Government had been appointed. Both Wellington and Blücher considered that they would not be acting in accordance with the spirit and intentions of the Coalition of the Powers were they to listen to such proposals, and therefore peremptorily refused to discontinue their operations.[85]

Armies dispositions evening of 24 June

The positions of the respective Armies on the evening of 24 June were as follows:

The Prussian I Corps and the IV were at Aisonville and Bernoville (a hamlet close to Aisonville) respectively. Blücher's headquarter were at Hannapes.[84][lower-alpha 19]

Anglo-allied:[84]

- The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd divisions of the Anglo-allied army were in and around Le Cateau-Cambrésis

- The 4th Division at Cambrai;

- The 5th and 6th divisions, the Brunswick Corps, and Reserve Artillery, at, and in the vicinity of Englefontaine.

- The Duke of Wellington's headquarter were at Le Cateau-Cambrésis .

The French troops under Soult were at Laon; those under Grouchy at Rethel.[84]

Aftermath

The next week (25 June – 1 July) would see the French reach Paris with the Coalition forces about a days march behind them. In the final week of the campaign (2–7 July) the French surrendered, Coalition forces entered Paris and on 8 July Louis XVIII was restored to the throne.

Notes

- ↑ See Prussian army order of battle

- ↑ Siborne spells this place Lermes

- ↑ Siborne spells it Bousseval

- ↑ Both the Ferraris van kaart of 1777 and Siborne calls this stream (or "small river") the Geneppe and what is now the Thyle the Dyle. However in the 19th century some contemporary sources noted that Geneppe was also called the Dyle, and today the Thyle is considered the tributary, and the Geneppe is now considered to be an upstream part of the Dyle.[19]

- ↑ 50°41′34″N 4°30′02″E / 50.69264°N 4.50051°E are the coordinates of Saint-Lambert

- ↑ Siborne calls it St Achtenrode

- ↑ or Halle

- ↑ Possibly Ernst Christian von Eicke.[29]

- ↑ Villers-Sire-Nicole is called Villers by Siborne

- ↑ Some sources such as William Siborne, who based his account on near contemporary German sources, use the spelling "Fallize" however other more modern sources use the spelling "La Falize".[34][35]

- ↑ "The lime trees along the drève [to the Château de Flawinne] still wear, embedded in their trunks, cannonballs launched during the fighting" .[37]

- ↑ Siborn spells it Flavinnes

- ↑ Siborme calls it the Wood of Villers (see Bois-de-Villers).

- 1 2 C.H. Gifford uses the behaviour of the Prussians after the surrender of the Fortress of Avesnes to highlight the different view of Blücher and Wellington in how to treat the French. The fortress had fallen with little loss of life to the besiegers, and to town was taken without an assault, but despite this great excesses were committed by the Prussian soldiery, on entering the town, which instead of being restrained was encouraged by their officers. The following letter will gives some idea of the manner in which this war was conducted by the Prussians.[64]

- To Major-general Dobschutz Military Governor &c.

- Head-quarters, at Noyelles-sur-Sambre, 21 June.

- Sir,—I inform you, by this letter, that the fortress of Avesnes fell into our power this morning and that the garrison are prisoners of war: and will be conveyed to Juliers. It were to be wished that some troops could be detached to relies the escort on the road. As for the prisoners, the officers are to be conducted to Wesel, and strictly guarded in the citadel; the soldiers are destined for Cologne, that they may be employed in working on the fortifications. All are to be treated with the necessary severity.

- (signed) Blücher[64]

- ↑ At least one British primary source misnames Baron Noos Baron Roos, so Roos is the name used by Siborne 1848, p. 684 and some other historians.

- ↑ Preux-au-Bois is spelt Préau-au-Bois by Siborne

- ↑ Pont-à-Bucy (49°41′25″N 3°29′07″E / 49.69019°N 3.48514°E)

- ↑ Siborn spells this Femy

- ↑ Siborne spells "Hannapes" "Henappe" in both the text and on his map, but he places it in the same location on the map as the place with the modern spelling.[84][86]

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 597.

- ↑ Parkinson 2000, p. 241.

- 1 2 3 Boyce 1816, p. 78.

- ↑ Barbero 2013, p. 298.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 277.

- ↑ Hugo 1907, p. 82.

- ↑ Bain 1816, p. 160.

- ↑ Hugo 1907, p. 83.

- ↑ Charras 1863, p. 317–318 (footnote).

- ↑ Uffindell 2006, p. 144.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 627.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 627–628.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 632.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 631.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 625.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 628.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 628–629.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 629.

- ↑ Kaart van Ferraris 1777, 'Cour St. Etienne' #96; Siborne 1848, p. 269; Siborne 1993, p. 5; Booth 1815, p. 67

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, pp. 629–630.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 630–631.

- ↑ Parkinson 2002, p. 283.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 632–633.

- 1 2 Siborne 1844, pp. 633–634.

- ↑ Siborne 1844, p. 635.

- ↑ Siborne 1844, p. 636.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 636.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 635,636.

- ↑ Schöning 1840, p. 266 (Entry 1304)

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 636–637.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 637.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 637–638.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 638.

- ↑ Kelly 1905, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Hofschröer 1999, p. 194.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 639.

- ↑ European Historic Houses Association team 2013, p. 24.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 640.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 640–641.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 641.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 641,642.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 642.

- ↑ Five 2007, Description (in French) of Namur's defences.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 642–643.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 643–644.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 644.

- ↑ Eye witness 1816, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Siborne 1848, p. 645.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 645,646.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 646.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 646,647.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 647.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, pp. 647,648.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 649.

- 1 2 3 4 Siborne 1848, p. 650.

- ↑ Kaart van Ferraris 1777, 'Binche' map 65.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 649–650.

- 1 2 3 4 Siborne 1848, p. 654.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 651.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 651–652.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 652.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 652–653.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 653–654.

- 1 2 3 4 Gifford 1817, p. 1494.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, pp. 655–656.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 659.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 660.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 660–661.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 676.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 676–677.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 677.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 677–678.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 678.

- ↑ Haweis 1908, pp. 309–310.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 678–679.

- ↑ Wellesley 1838, pp. 503–504.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 684.

- ↑ Lennox 1851, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 Siborne 1848, p. 679.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, p. 680.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 680–681.

- 1 2 Siborne 1848, p. 681.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 681–682.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Siborne 1848, p. 682.

- ↑ Siborne 1848, pp. 679–680.

- ↑ Siborne 1844, Plate 11.

References

- Bain, Nicolson (1816), A detailed account of the battles of Quatre Bras, Ligny, and Waterloo: preceded by a short relation of events, attending the temporary revolution of 1815, in France, London, p. 160

- Barbero, Alessandro (2013), The Battle, Atlantic Books, p. 298, ISBN 9781782391388

- Booth, John (1815), The Battle of Waterloo: Containing the Accounts Published by Authority, British and Foreign, and Other Relative Documents, with Circumstantial Details, Previous and After the Battle, from a Variety of Authentic and Original Sources : to which is Added an Alphabetical List of the Officers Killed and Wounded, from 15th to 26th June, 1815, and the Total Loss of Each Regiment, J. Booth, p. 67

- Boyce, Edmund (1816), The Second Usurpation of Buonaparte; Or a History of the Causes, Progress and Termination of the Revolution in France in 1815 2, Leigh, p. 78

- Charras, Jean Baptiste Adolphe (1863), Histoire de la campagne de 1815 (4th ed.), Lacroix, Verboeckhoven etce, pp. 317–318

- European Historic Houses Association team (26–29 September 2013), General Assembly European Historic Houses Association (PDF), Brussels, pp. 24–25, Conference

- Eye witness (1816), "Appendix 24", The journal of the three days of the battle of Waterloo, by an eye-witness. To which is added an appendix containing the official reports of the allies, p. 26

- Five, Jean et Emmanuel (2007), Les fortifications de la ville de Namur (PDF)