Mark and recapture

Mark and recapture is a method commonly used in ecology to estimate an animal population's size. A portion of the population is captured, marked, and released. Later, another portion is captured and the number of marked individuals within the sample is counted. Since the number of marked individuals within the second sample should be proportional to the number of marked individuals in the whole population, an estimate of the total population size can be obtained by dividing the number of marked individuals by the proportion of marked individuals in the second sample. The method is most useful when it is not practical to count all the individuals in the population. Other names for this method, or closely related methods, include capture-recapture, capture-mark-recapture, mark-recapture, sight-resight, mark-release-recapture, multiple systems estimation, band recovery, the Petersen method,[1] and the Lincoln method.

Another major application for these methods is in epidemiology,[2] where they are used to estimate the completeness of ascertainment of disease registers. Typical applications include estimating the number of people needing particular services (i.e. services for children with learning disabilities, services for medically frail elderly living in the community), or with particular conditions(i.e. illegal drug addicts, people infected with HIV, etc.).

Field work related to mark-recapture

Typically a researcher visits a study area and uses traps to capture a group of individuals alive. Each of these individuals is marked with a unique identifier (e.g., a numbered tag or band), and then is released unharmed back into the environment. A mark recapture method was first used for ecological study in 1896 by C.G. Johannes Petersen to estimate plaice, Pleuronectes platessa, populations.[3]

Sufficient time is allowed to pass for the marked individuals to redistribute themselves among the unmarked population.

Next, the researcher returns and captures another sample of individuals. Some individuals in this second sample will have been marked during the initial visit and are now known as recaptures. Other animals captured during the second visit will not have been captured during the first visit to the study area. These unmarked animals are usually given a tag or band during the second visit and then are released.

Population size can be estimated from as few as two visits to the study area. Commonly, more than two visits are made, particularly if estimates of survival or movement are desired. Regardless of the total number of visits, the researcher simply records the date of each capture of each individual. The "capture histories" generated are analyzed mathematically to estimate population size, survival, or movement.

In the epidemiological setting, different sources of patients take the place of the repeated field visits in ecology. To take a concrete example, establishing a register of children with Type 1 diabetes children were identified from hospital admission records, from general practitioners (family doctors), and from the records of the local Diabetes Association. None of these sources had a complete list, but by putting them together it was possible to do two things, first to see how many children were identified in total, and secondly to estimate how many more children with Type 1 diabetes were living in the vital community.

Notation

Let

- N = Number of animals in the population

- K = Number of animals marked on the first visit

- n = Number of animals captured on the second visit

- k = Number of recaptured animals that were marked

A biologist wants to estimate the size of a population of turtles in a lake. She captures 10 turtles on her first visit to the lake, and marks their backs with paint. A week later she returns to the lake and captures 15 turtles. Five of these 15 turtles have paint on their backs, indicating that they are recaptured animals. This example is (K, n, k) = (10, 15, 5). The problem is to estimate N.

Lincoln–Petersen estimator

The Lincoln–Petersen method[4] (also known as the Petersen–Lincoln index[3] or Lincoln index) can be used to estimate population size if only two visits are made to the study area. This method assumes that the study population is "closed". In other words, the two visits to the study area are close enough in time so that no individuals die, are born, move into the study area (immigrate) or move out of the study area (emigrate) between visits. The model also assumes that no marks fall off animals between visits to the field site by the researcher, and that the researcher correctly records all marks.

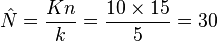

Given those conditions, estimated population size is:

Derivation

It is assumed[5] that all individuals have the same probability of being captured in the second sample, regardless of whether they were previously captured in the first sample (with only two samples, this assumption cannot be tested directly).

This implies that, in the second sample, the proportion of marked individuals that are caught ( ) should equal the proportion of the total population that is caught (

) should equal the proportion of the total population that is caught ( ). For example, if half of the marked individuals were recaptured, it would be assumed that half of the total population was included in the second sample.

). For example, if half of the marked individuals were recaptured, it would be assumed that half of the total population was included in the second sample.

In symbols,

A rearrangement of this gives

the formula used for the Lincoln–Petersen method.[5]

Sample calculation

In the example (K, n, k) = (10, 15, 5) the Lincoln–Petersen method estimates that there are 30 turtles in the lake.

Chapman estimator

The Lincoln–Peterson estimator is asymptotically unbiased as sample size approaches infinity, but is biased at small sample sizes.[6] An alternative less biased estimator of population size is given by the Chapman estimator:[6]

Sample calculation

The example (K, n, k) = (10, 15, 5) gives

Note that the answer provided by this equation must be truncated not rounded. Thus, the Chapman method estimates 28 turtles in the lake.

Surprisingly, Chapman's estimate was one conjecture from a range of possible estimators: "In practice, the whole number immediately less than (K+1)(n+1)/(k+1) or even Kn/(k+1) will be the estimate. The above form is more convenient for mathematical purposes."[6](see footnote, page 144). Chapman also found the estimator could have considerable negative bias for small Kn/N [6](page 146), but was unconcerned because the estimated standard deviations were large for these cases.

A Bayesian analysis[7] found that Chapman's estimator is the maximum a posteriori estimator for a situation when the first person searches for a fixed number of animals then marks and releases them, but the second person searches for as many animals as possible.

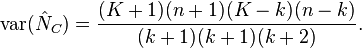

Variance

An approximately unbiased variance of  can be estimated as:

can be estimated as:

The moments of the hypergeometric equation studied by Chapman can be calculated exactly, giving the answers discussed below.

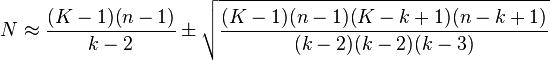

Confidence interval

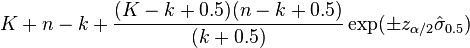

An approximate  confidence interval for the population size N can be obtained as:

confidence interval for the population size N can be obtained as:

,

,

where  corresponds to the

corresponds to the  quantile of a standard normal random variable, and

quantile of a standard normal random variable, and

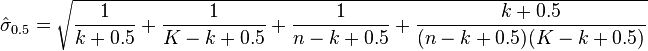

.

.

It has been shown that this confidence interval has actual coverage probabilities that are close to the nominal  level even for small populations and extreme capture probabilities (near to 0 or 1), in which cases other confidence intervals fail to achieve the nominal coverage levels.[8]

level even for small populations and extreme capture probabilities (near to 0 or 1), in which cases other confidence intervals fail to achieve the nominal coverage levels.[8]

Bayesian estimate

A Bayesian analysis is provided by.[7] The final answer depends on the priors and the type of search assumed but the approach gives, for Chapman's assumptions (and changing variables from the original notation),

Mean value ± standard deviation

A derivation is found here: Talk:Mark and recapture#Statistical treatment.

Sample calculation

The example (K, n, k) = (10, 15, 5) gives the estimate N ≈ 42 ± 21.5

More than two visits

The literature on the analysis of capture-recapture studies has blossomed since the early 1990s. There are very elaborate statistical models available for the analysis of these experiments.[9] A simple model which easily accommodates the three source, or the three visit study, is to fit a Poisson regression model. Sophisticated mark-recapture models can be fit using Rcapture,[10] a package of the Open Source R programming language, or specialized programs such as MARK[11] or M-SURGE.[12] Other related methods which are often used include the Jolly–Seber model (used in open populations and for multiple census estimates) and Schnabel estimators (described above as an expansion to the Lincoln–Peterson method for closed populations). These are described in detail by Sutherland.[13]

Integrated approaches

Modelling mark-recapture data is trending towards a more integrative approach,[14] which combines mark-recapture data with population dynamics models and other types of data. The integrated approach is more computationally demanding, but extracts more information from the data improving parameter and uncertainty estimates.[15]

See also

- German tank problem, for estimation of population size when the elements are numbered.

- Tag and release

- Abundance estimation

References

- ↑ Krebs, Charles J. (2009). Ecology (6th ed.). p. 119. ISBN 978-0-321-50743-3.

- ↑ Chao, A., Tsay, P. K., Lin, S. H., Shau, W. Y., and Chao, D. Y., 2001, The applications of capture-recapture models to epidemiological data, Statistics in Medicine, volume 20, issue 20, pages 3123–3157, doi 10.1002/sim.996

- 1 2 Southwood, T.R.E. & Henderson, P. (2000) Ecological Methods, 3rd edn. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

- ↑ Seber, G.A.F.. The Estimation of Animal Abundance and Related Parameters. Caldwel, New Jersey: Blackburn Press. ISBN 1-930665-55-5

- 1 2 Charles J. Krebs (1999). Ecological Methodology (2nd ed.).

- 1 2 3 4 Chapman, D.G. (1951). "Some properties of the hypergeometric distribution with applications to zoological sample censuses".

- 1 2 Webster and Kemp (2013)"Estimating Omissions From Searches.". Retrieved 15 Dec 2014.

- ↑ Sadinle, Mauricio (2009-10-01). "Transformed Logit Confidence Intervals for Small Populations in Single Capture–Recapture Estimation". Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation 38 (9): 1909–1924. doi:10.1080/03610910903168595. ISSN 0361-0918.

- ↑ McCrea, R.S. and Morgan, B.J.T. (2014) "Analysis of capture-recapture data.". Retrieved 19 Nov 2014. "Chapman and Hall/CRC Press". Retrieved 19 Nov 2014.

- ↑ "CRAN – Package Rcapture". Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Program MARK". Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ "Logiciels".

- ↑ William J. Sutherland, ed. (1996). Ecological Census Techniques: A Handbook. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47815-4.

- ↑ Maunder M.N. (2003) Paradigm shifts in fisheries stock assessment: from integrated analysis to Bayesian analysis and back again. Natural Resource Modeling 16:465–475

- ↑ Maunder, M.N. (2001) Integrated Tagging and Catch-at-Age Analysis (ITCAAN). In Spatial Processes and Management of Fish Populations, edited by G.H. Kruse,N. Bez, A. Booth, M.W. Dorn, S. Hills, R.N. Lipcius, D. Pelletier, C. Roy, S.J. Smith, and D. Witherell, Alaska Sea Grant College Program Report No. AK-SG-01-02, University of Alaska Fairbanks, pp. 123–146.

- Besbeas, P; Freeman, S. N.; Morgan, B. J. T.; Catchpole, E. A. (2002). "Integrating mark-recapture-recovery and census data to estimate animal abundance and demographi parameters.". Biometrics 58 (3): 540–547. doi:10.1111/j.0006-341X.2002.00540.x. PMID 12229988.

- Martin-Löf, P. (1961). "Mortality rate calculations on ringed birds with special reference to the Dunlin Calidris alpina". Arkiv för Zoologi (Zoology files), Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademien (The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences) Serie 2. Band 13 (21).

- Maunder, M. N. (2004). "Population viability analysis, based on combining integrated, Bayesian, and hierarchical analyses". Acta Oecologica 26 (2): 85–94. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2003.11.008.

- Phillips, C. A.; M. J. Dreslik; J. R. Johnson; J. E. Petzing (2001). "Application of population estimation to pond breeding salamanders". Transactions of the Illinois Academy of Science 94 (2): 111–118.

- Royle, J. A.; R. M. Dorazio (2008). Hierarchical Modeling and Inference in Ecology. Elsevier. ISBN 1-930665-55-5.

- Seber, G.A.F. The Estimation of Animal Abundance and Related Parameters. Caldwel,New Jersey: Blackburn Press. ISBN 1-930665-55-5.

- Schaub, M; Gimenez, O.; Sierro, A.; Arlettaz, R (2007). "Use of Integrated Modeling to Enhance Estimates of Population Dynamics Obtained from Limited Data". Conservation Biology 21 (4): 945–955. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00743.x. PMID 17650245.

- Williams, B. K.; J. D. Nichols; M. J. Conroy (2002). Analysis and Management of Animal Populations. San Diego, California: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-754406-2.

- Chao, A; Tsay, P. K.; Lin, S. H.; Shau, W. Y.; Chao, D. Y. (2001). "The applications of capture-recapture models to epidemiological data". Statistics in Medicine 20 (20): 3123–3157. doi:10.1002/sim.996.

- Webster, A. J.; Kemp, R. (2013). "Estimating Omissions from Searches". The American Statistician 67 (2): 82–89. doi:10.1080/00031305.2013.783881.

Further reading

- Bonett, D.G., Woodward, J.A., & Bentler, P.M. (1986). "A Linear Model for Estimating the Size of a Closed Population", British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 39, 28–40.

- Evans, M.A., Bonett, D.G., & McDonald, L. (1994). "A General Theory for Analyzing Capture-recapture Data in Closed Populations." Biometrics, 50, 396–405.

- Lincoln, F. C. (1930). "Calculating Waterfowl Abundance on the Basis of Banding Returns". United States Department of Agriculture Circular, 118, 1–4.

- Petersen, C. G. J. (1896). "The Yearly Immigration of Young Plaice Into the Limfjord From the German Sea", Report of the Danish Biological Station (1895), 6, 5–84.

- Schofield, J. R. (2007). "Beyond Defect Removal: Latent Defect Estimation With Capture-Recapture Method", Crosstalk, August 2007; 27–29.