Projection (mathematics)

In mathematics, a projection is a mapping of a set (or other mathematical structure) into a subset (or sub-structure), which is equal to its square for mapping composition (or, in other words, which is idempotent). The restriction to a subspace of a projection is also called a projection, even if the idempotence property is lost. An everyday example of a projection is the casting of shadows onto a plane (paper sheet). The projection of a point is its shadow on the paper sheet. The shadow of a point on the paper sheet is this point itself (idempotence). The shadow of a three-dimensional sphere is a circle. Originally, the notion of projection was introduced in Euclidean geometry to denote the projection of the Euclidean space of three dimensions onto a plane in it, like the shadow example. The two main projections of this kind are:

- The projection from a point onto a plane or central projection: If C is a point, called the center of projection, then the projection of a point P different from C onto a plane that does not contain C is the intersection of the line CP with the plane. The points P such that the line CP is parallel to the plane do not have any image by the projection, but one often says that they project to a point at infinity of the plane (see projective geometry for a formalization of this terminology). The projection of the point C itself is not defined.

- The projection parallel to a direction D, onto a plane: The image of a point P is the intersection with the plane of the line parallel to D passing through P. See Affine space § Projection for an accurate definition, generalized to any dimension.

The concept of projection in mathematics is a very old one, most likely having its roots in the phenomenon of the shadows cast by real world objects on the ground. This rudimentary idea was refined and abstracted, first in a geometric context and later in other branches of mathematics. Over time differing versions of the concept developed, but today, in a sufficiently abstract setting, we can unify these variations.

In cartography, a map projection is a map of a part of the surface of the Earth onto a plane, which, in some cases, but not always, is the restriction of a projection in the above meaning. The 3D projections are also at the basis of the theory of perspective.

The need for unifying the two kinds of projections and of defining the image by a central projection of any point different of the center of projection are at the origin of projective geometry. However, a projective transformation is a bijection of a projective space, a property not shared with the projections of this article.

Definition

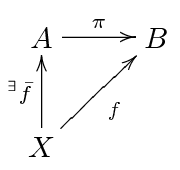

In an abstract setting we can generally say that a projection is a mapping of a set (or of a mathematical structure) which is idempotent, which means that a projection is equal to its composition with itself. A projection may also refer to a mapping which has a left inverse. Both notions are strongly related, as follows. Let p be an idempotent map from a set E into itself (thus p∘p = p) and F = p(E) be the image of p. If we denote by π the map p viewed as a map from E onto F and by i the injection of F into E, then we have i∘π = IdF. Conversely, i∘π = IdF implies that π∘i is idempotent.

Applications

The original notion of projection has been extended or generalized to various mathematical situations, frequently, but not always, related to geometry, for example:

- In set theory:

- An operation typified by the j th projection map, written projj , that takes an element x = (x1, ..., xj , ..., xk) of the cartesian product X1 × … × Xj × … × Xk to the value projj (x) = xj . This map is always surjective.

- A mapping that takes an element to its equivalence class under a given equivalence relation is known as the canonical projection.

- The evaluation map sends a function f to the value f(x) for a fixed x. The space of functions YX can be identified with the cartesian product

, and the evaluation map is a projection map from the cartesian product.

, and the evaluation map is a projection map from the cartesian product.

- In category theory, the above notion of cartesian product of sets can be generalized to arbitrary categories. The product of some objects has a canonical projection morphism to each factor. This projection will take many forms in different categories. The projection from the Cartesian product of sets, the product topology of topological spaces (which is always surjective and open), or from the direct product of groups, etc. Although these morphisms are often epimorphisms and even surjective, they do not have to be.

- In linear algebra, a linear transformation that remains unchanged if applied twice (p(u) = p(p(u))), in other words, an idempotent operator. For example, the mapping that takes a point (x, y, z) in three dimensions to the point (x, y, 0) in the plane is a projection. This type of projection naturally generalizes to any number of dimensions n for the source and k ≤ n for the target of the mapping. See orthogonal projection, projection (linear algebra). In the case of orthogonal projections, the space admits a decomposition as a product, and the projection operator is a projection in that sense as well.

- In differential topology, any fiber bundle includes a projection map as part of its definition. Locally at least this map looks like a projection map in the sense of the product topology, and is therefore open and surjective.

- In topology, a retract is a continuous map r: X → X which restricts to the identity map on its image. This satisfies a similar idempotency condition r2 = r and can be considered a generalization of the projection map. A retract which is homotopic to the identity is known as a deformation retract. This term is also used in category theory to refer to any split epimorphism.

- The scalar projection (or resolute) of one vector onto another.

References

Further reading

- Thomas Craig (1882) A Treatise on Projections from University of Michigan Historical Math Collection.